Governance Tech: E-governance, Policy, Data & Engagement

Executive Summary

The rapid integration of digital technologies into public administration is fundamentally reshaping the relationship between the state, its citizens, and the global community. This report provides a comprehensive analysis of Public Administration and Governance Technology (“GovTech”), examining the foundational architectures, profound policy challenges, and transformative potential of this digital revolution. The analysis reveals a global trend towards e-governance, yet one marked by significant disparities and complex trade-offs. While digital platforms promise unprecedented efficiency in service delivery and new avenues for citizen engagement, their implementation is fraught with challenges, including persistent digital divides, formidable cybersecurity threats, and the risk of algorithmic bias.

The report is structured into five parts. Part I explores the foundational pillars of the digital state: e-governance frameworks and digital identity systems. It charts the evolution from basic online information portals to sophisticated, interactive service delivery models, and analyzes the successes and failures of national digital ID programs, which serve as the bedrock of digital interaction. Part II delves into the critical regulatory challenges confronting modern governments as they grapple with the nexus of technology and policy. It provides a comparative analysis of global data privacy regimes, most notably the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and examines the emerging governance frameworks for artificial intelligence (AI) and the complex task of regulating social media platforms to protect democratic discourse.

Part III shifts focus to the proactive and innovative dimensions of GovTech, investigating how open government data (OGD) acts as a powerful catalyst for economic growth and social innovation. It details the symbiotic relationship between open data and the burgeoning field of civic technology (civic tech), which empowers citizens to engage more directly with their governments and co-create public value. Part IV synthesizes the overarching, cross-cutting challenges that threaten to undermine the promise of digital transformation. It addresses the imperative of bridging the digital divide to ensure inclusivity, the escalating risks of state surveillance and cybersecurity breaches that erode public trust, and the complex geopolitical discourse surrounding digital rights and national sovereignty.

Finally, Part V looks to the future, assessing the potential impact of next-generation technologies like blockchain, quantum computing, and the metaverse on public administration. The report concludes with a set of strategic, actionable recommendations for policymakers and public administrators. These recommendations emphasize the need for a holistic, “whole-of-government” approach that prioritizes inclusivity, embeds rights and ethics by design, fosters innovation through open ecosystems, invests in public sector capacity, embraces adaptive regulation, and strengthens international cooperation. Ultimately, this report argues that the successful construction of the digital state depends not merely on technological adoption, but on the political will to build systems that are transparent, accountable, and fundamentally oriented toward the public good.

Part I: The Architecture of Digital Government: E-Governance and Identity

This part establishes the foundational pillars of the digital state, examining the structures through which governments deliver services and the systems they use to identify citizens in the digital realm.

Section 1: Frameworks for E-Governance and Service Delivery

1.1 The Evolution of E-Governance: From Digital Presence to Transformation

The integration of technology into public administration has evolved from a peripheral concern to a central pillar of modern statecraft. At its core, this transformation is captured by the concept of e-governance.

Defining E-Governance

E-governance, or electronic governance, is the strategic application of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to provide and improve government services, information exchange, and the integration of various administrative systems. Its primary objectives extend beyond mere digitization; they aim to create a more efficient, transparent, accountable, and participatory government. This involves leveraging digital tools to streamline processes, reduce bureaucratic inefficiencies, and ultimately bridge the gap between public institutions and the citizens they serve. The ultimate goal is to foster a system of governance that is more responsive to public needs and enhances trust between the state and its constituents.

Distinguishing E-Government from E-Governance

A critical distinction exists between “e-government” and “e-governance.” E-government typically refers to the more narrowly defined act of using ICT to deliver public services—essentially, moving existing government functions online. It is primarily concerned with the efficiency of the state’s internal operations and its service delivery mechanisms. E-governance, in contrast, represents a broader and more profound paradigm shift. It encompasses not only the digital delivery of services but also the transformation of the democratic process itself, emphasizing citizen participation, collaborative decision-making, and the use of technology to alter the fundamental relationship between the government and the governed. While e-government is about making the existing state more efficient, e-governance is about creating a more open, networked, and democratic state. This distinction is vital for assessing the true maturity of a nation’s digital strategy; a state may excel at e-government by offering a wide array of online services, yet lag in e-governance by failing to foster meaningful digital participation.

Maturity Models

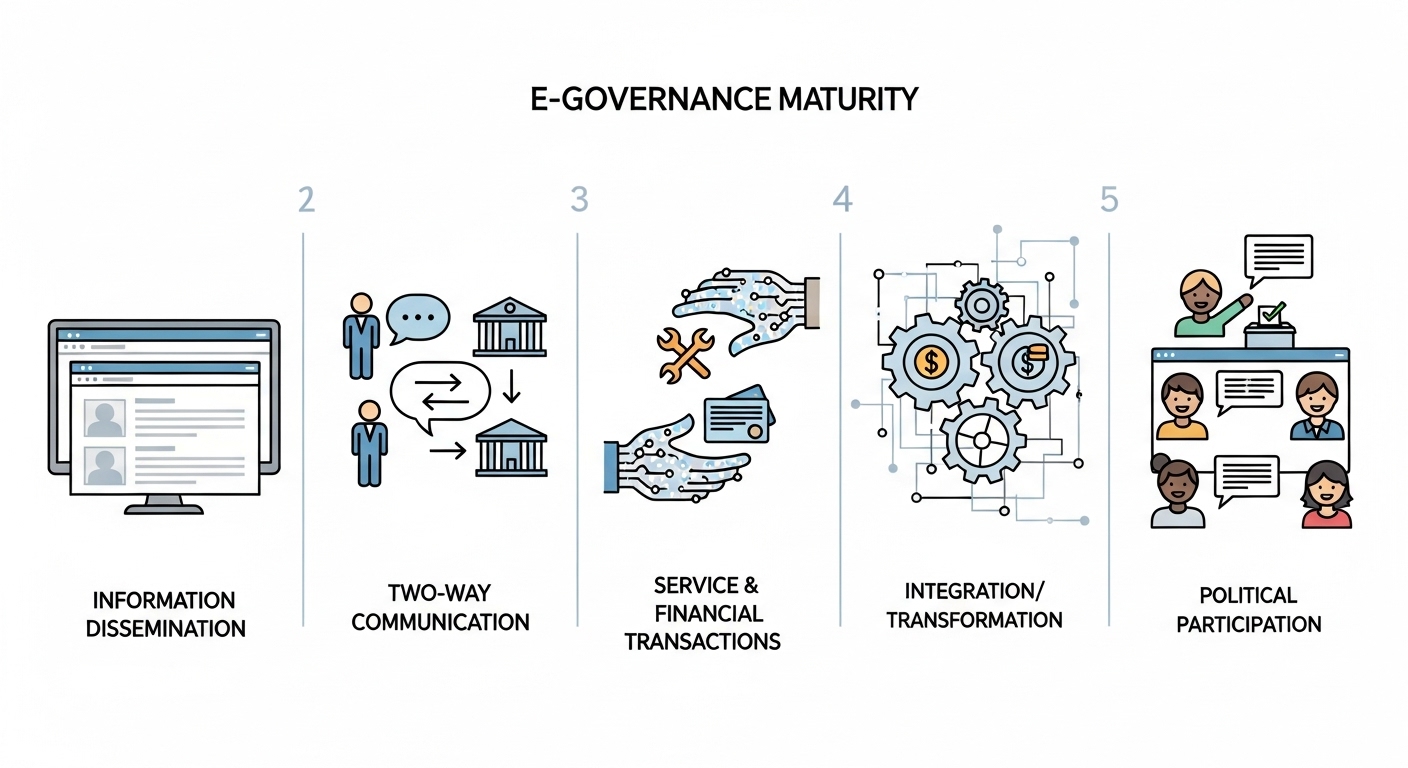

The progression from a simple digital presence to a fully transformed system of e-governance can be understood through theoretical maturity models. These models typically delineate several stages of development:

- Information Dissemination (Presence): The initial stage involves creating a basic web presence where government agencies publish information. This is a one-way communication channel, akin to an online brochure.

- Two-Way Communication (Interaction): The next level introduces interactivity, allowing citizens to make requests, provide feedback, or communicate with public administrators through email, online forms, or messaging systems.

- Service and Financial Transactions: This stage marks the transition to true e-government, where citizens can conduct transactions online, such as paying taxes, applying for licenses, or receiving benefits.

- Integration (Transformation): Here, government systems become integrated both vertically (across different levels of government) and horizontally (across different agencies). This “whole-of-government” approach provides seamless, citizen-centric services.

- Political Participation (Digital Democracy): The highest level of maturity, where technology is used to facilitate full political participation, including e-voting, online policy consultations, and collaborative governance, thereby realizing the vision of e-governance.

This evolutionary path highlights a critical challenge in digital transformation. While the technological steps of building websites and transactional portals are relatively straightforward, the political and institutional reforms required to achieve genuine integration and participation are far more difficult. This creates an “e-governance maturity paradox,” where a nation can appear digitally advanced based on its service delivery infrastructure but remain fundamentally immature in its democratic engagement, having mastered the tools of e-government without embracing the principles of e-governance.

1.2 Analyzing Service Delivery Models: G2C, G2B, G2G, and G2E in Practice

E-governance frameworks are typically categorized by the primary stakeholders they serve. These models—Government-to-Citizen (G2C), Government-to-Business (G2B), Government-to-Government (G2G), and Government-to-Employee (G2E)—form the operational architecture of the digital state.

- Government-to-Citizen (G2C): This is the most visible facet of e-governance, focusing on the direct interface between the state and the public. G2C initiatives aim to make services more convenient and accessible, allowing citizens to perform tasks such as paying taxes, applying for permits and grants, or updating personal information online or via mobile devices. Beyond transactional services, the G2C model also includes platforms for e-Participation, such as electronic voting, online opinion polling, and direct messaging with public officials, which are designed to enhance civic engagement.

- Government-to-Business (G2B): The G2B model is designed to improve the efficiency of the government’s relationship with the private sector. The primary goal is to reduce the administrative burden on businesses by streamlining regulatory processes. This includes online systems for permits and licenses, tax filing, procurement, and economic development information. A key principle often adopted in advanced G2B systems is “collect data once for multiple uses,” which streamlines redundant data collection and simplifies compliance for businesses.

- Government-to-Government (G2G): This model focuses on enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of interactions within government.

G2G initiatives facilitate secure data sharing and collaboration between different agencies, departments, and levels of government (e.g., federal, state, and local). By breaking down informational silos, G2G systems improve coordination, reduce duplication of effort, and enable a more holistic approach to policymaking and service delivery.

- Government-to-Employee (G2E): The G2E model applies e-governance principles to the internal workings of public administration. It involves the use of online tools and platforms to manage human resources and empower public sector employees. This includes systems for maintaining personal records, facilitating online training and distance learning, and enabling paperless communication and document sharing among colleagues. G2E initiatives aim to create a more efficient, knowledgeable, and responsive civil service.

1.3 A Spectrum of Engagement: From Broadcasting to Interactive-Service Models

Beyond the stakeholder-based models, e-governance can also be understood through a spectrum of engagement, reflecting the depth and nature of the interaction between the government and the public. These models range from simple information provision to complex, co-creative service delivery.

- Broadcasting Model: This is the most fundamental and common model, characterized by one-way communication where the government disseminates information to the public via websites, online bulletins, or official portals. Its strength lies in its simplicity and efficiency for mass communication of official policies and updates. However, its primary weakness is the complete lack of citizen engagement or feedback, which can lead to a sense of exclusion.

- Critical Flow Model: This model represents a significant step forward by emphasizing a two-way, dynamic flow of information. It is designed to be interactive and responsive, allowing governments to solicit public queries and concerns and respond in near real-time. This fosters a more inclusive form of governance by promoting dialogue and participation. A prominent example is India’s MyGov platform, which allows citizens to engage in policy discussions and submit ideas directly to the government.

- Comparative Analysis Model: In this model, the government actively involves citizens in the decision-making process by presenting different policy solutions or strategies for public feedback. This facilitates a data-driven dialogue, allowing for more informed decisions that reflect public opinion and diverse perspectives. Its primary weakness is that it can be time-consuming and resource-intensive.

- E-Advocacy/Mobilization Model: This model harnesses digital platforms to empower citizens and civil society organizations to advocate for policy changes and mobilize support for specific causes. It leverages tools like social media, online petitions, and email campaigns to create awareness and pressure for governmental action. This model has been effectively used in India for campaigns such as #SaveOurRivers, demonstrating its power to amplify grassroots movements.

- Interactive-Service Model: Representing the most advanced and dynamic approach, this model focuses on the direct delivery of transactional digital services. Citizens can interact with government agencies through online portals or mobile apps to apply for permits, pay taxes, or access benefits. This model aims to maximize efficiency, accessibility, and convenience, fundamentally changing the nature of service delivery. India’s Digital India programme, with services like the DigiLocker for digital documents, exemplifies this highly developed model.

1.4 Global Benchmarks and Case Studies: Lessons from International Experience

The global adoption of e-governance is tracked and measured through various international benchmarks, providing a comparative perspective on national progress and highlighting both successes and persistent challenges.

The United Nations E-Government Development Index (EGDI) is the foremost global benchmark, assessing the digital government landscape across all 193 Member States based on telecommunication infrastructure, human capital, and online service provision. The 2024 UN E-Government Survey indicates a significant upward trend in digital government development worldwide. The proportion of the global population lagging in this area has decreased from 45% in 2022 to 22.4% in 2024, reflecting increased investment in digital infrastructure and services, particularly in the post-pandemic era. However, the survey also underscores a persistent and deep digital divide. The EGDI averages for Africa, Least Developed Countries (LDCs), and Small Island Developing States remain well below the global average, suggesting that at the current pace, these regions may not bridge the digital gap by 2030. Geographically, Europe and Asia continue to lead, while the United States has slipped from 10th to 19th in the rankings, partly due to gaps in broadband coverage.

Several countries stand out as exemplars of successful e-governance implementation:

- Estonia: Widely recognized as a global leader, Estonia has built a comprehensive, citizen-centric digital society where nearly all public services are accessible online. Its success is rooted in a strong political commitment, a robust legal framework, and a foundational digital identity system that underpins all interactions.

- South Korea: Consistently ranked among the top performers, South Korea has leveraged its advanced technological infrastructure and high levels of digital literacy to create a highly efficient and accessible e-government system.

- Denmark and Finland: These Nordic countries are also top performers, demonstrating a commitment to digital innovation, accessibility, and citizen-centric service design, with well-developed digital ID and online tax services.

Conversely, the experience of many developing nations highlights the significant barriers to successful implementation. E-governance projects in these contexts often face a high failure ratio. The primary reasons for failure are multifaceted and systemic, including inadequate ICT infrastructure, low digital literacy among both citizens and public officials, persistent bureaucratic resistance to change, and the disruptive effects of political instability on long-term planning and investment. India presents a complex case, showcasing both massive successes in scale, such as the Aadhaar digital ID system and the Digital India program, alongside profound challenges of exclusion and a deep-rooted digital divide that prevents equitable access to these services. These cases underscore that successful e-governance is not merely a technological challenge but a complex socio-political one that requires sustained investment, institutional reform, and a steadfast commitment to inclusivity.

Digital Identity as a Cornerstone of the Modern State

In the digital era, the ability of a state to uniquely and reliably identify its citizens is no longer just an administrative function; it is the foundational infrastructure upon which all modern e-governance services are built. A robust digital identity system is the cornerstone of the digital state, enabling secure access, personalized services, and trusted transactions.

2.1 Principles of Identity and Access Management (IAM) in the Public Sector

Identity and Access Management (IAM) provides the conceptual and technical framework for managing digital identities in the public sector. It is defined as a system of policies and technologies designed to ensure that the right users have the appropriate access to technology resources, and no more. This principle of “least privilege” is fundamental to securing government systems and citizen data.

The core functions of an IAM framework can be broken down into a lifecycle:

- Identification and Registration: The process of creating a unique digital identity for an individual, often tied to foundational documents or biometric data.

- Authentication: The mechanism for verifying that a user is who they claim to be. This can range from simple passwords to more secure methods like biometrics (fingerprints, facial recognition), hardware tokens, or Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA), which combines multiple verification methods.

- Authorization: Once authenticated, the system determines what resources, services, or data the user is permitted to access based on their roles and permissions.

- Lifecycle Management: This involves the continuous management of an identity, including updating access rights when a user’s role changes (e.g., a change in eligibility for a social benefit) and promptly revoking all access when a user is no longer authorized (e.g., upon death), which is crucial for preventing fraud.

The technical underpinnings of modern IAM systems rely heavily on open, international standards such as Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML 2.0), OAuth, and OpenID. The adoption of these standards is critical for ensuring interoperability between different government systems and services, and for preventing “vendor lock-in,” where a government becomes dependent on a single proprietary technology provider.

2.2 Building Trust and Security: Technical Standards and Policy Frameworks

The success of any digital ID program hinges on public trust. Citizens will only adopt and use a digital ID if they believe their personal data is secure and their privacy is protected. This requires a robust combination of technical standards and strong policy frameworks.

The World Bank’s Identification for Development (ID4D) Initiative has emerged as a key global actor in this space.

The ID4D initiative works with countries to help them build inclusive and trusted digital ID systems that can unlock development outcomes and help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. The initiative emphasizes a holistic approach that integrates technology with strong governance, legal frameworks, and safeguards to protect citizen rights.

A central principle advocated by the ID4D initiative and other global experts is “Privacy-and-Security-by-Design”. This approach mandates that data protection and security measures are not treated as add-ons but are embedded into the fundamental architecture of the ID system from its very inception. This involves proactive measures such as conducting comprehensive Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) before deployment to identify and mitigate privacy risks, as well as continuous security audits and penetration testing throughout the system’s lifecycle to defend against evolving cyber threats.

2.3 Successes and Failures in National Digital ID Programs: A Comparative Analysis

The global landscape of national digital ID programs is a study in contrasts, offering valuable lessons from both successes and failures. The World Bank’s analysis of numerous country experiences reveals a set of common success factors, including: an outcome-based design that is tailored to the specific local context and needs; sustained high-level political commitment; a strong and clear legal framework that protects rights; meaningful public engagement to build trust and ensure usability; and the use of open international standards to ensure interoperability and avoid vendor lock-in.

Case Study: India’s Aadhaar

India’s Aadhaar system is arguably the world’s largest and most ambitious digital ID program. It is often cited as a success story for its sheer scale (over a billion enrollments) and its role as a foundational platform for transformative government initiatives, most notably in enabling direct benefit transfer programs that have streamlined the delivery of social welfare. Key factors contributing to its success include its design for massive scale, its focus on providing a unique number rather than a physical card, and, crucially, its policy of separating the act of identification from questions of legal status or citizenship. This last point was a deliberate design choice to promote inclusion and ensure that even marginalized populations could be enrolled.

However, many digital ID initiatives falter or fail outright. Common failure points often have less to do with technology and more to do with governance and user experience. Many projects fail because they misjudge complex legal and compliance requirements, treat identity as a simple IT project rather than a profound socio-political one, and vastly underestimate the challenges of achieving widespread user adoption. The case of Catalonia’s digital ID system highlights this user friction vividly; despite the system’s availability, a staggering 50% of users would forget their credentials and request a new e-ID for each new interaction with the government, indicating a fundamental failure in user experience design. These examples are symptomatic of broader digital transformation failures, which are often rooted in a lack of clear strategic direction, cultural resistance within government agencies, and the immense difficulty of integrating new systems with outdated legacy infrastructure.

This evidence demonstrates that digital ID is not a neutral technological tool. It is a foundational public good, but a highly contentious one. Its implementation creates an inherent tension between the state’s legitimate goals of efficiency, security, and administrative legibility, and the fundamental rights of citizens to privacy, autonomy, and inclusion. The success of a digital ID program is therefore not merely a technical achievement but a reflection of a state’s ability to navigate this tension and strike a balance that earns the trust and confidence of its people. A system designed purely for state efficiency without prioritizing user experience and robust rights protection is likely to fail.

2.4 Mitigating Risks: Addressing Exclusion, Privacy, and Vendor Lock-in

The implementation of national digital ID systems carries significant risks that must be proactively managed to avoid causing harm.

- Exclusion: This is arguably the most severe risk from a development perspective. When a government makes a specific digital ID mandatory for accessing essential services like healthcare, social programs, or voting, it risks excluding the most vulnerable segments of the population. Individuals in remote areas, the forcibly displaced, ethnic minorities, and those who lack the necessary foundational documents (like a birth certificate) may be unable to enroll. Furthermore, technological failures, such as biases in biometric authentication systems that perform less accurately for certain demographic groups, can also lead to exclusion. Mitigating this risk requires explicit and deliberate strategies for inclusion, such as outreach campaigns, minimizing documentation requirements, and providing alternative, non-digital pathways to access services.

- Privacy and Security Violations: The creation of large, centralized databases containing sensitive personal and biometric data of an entire population creates a high-value target for cybercriminals and a powerful tool for state surveillance. The risks of data theft, misuse for social control or discrimination, and identity fraud are immense. Strong legal frameworks for data protection, coupled with state-of-the-art cybersecurity and a “privacy-by-design” approach, are essential but not always sufficient safeguards.

- Vendor or Technology Lock-in: Governments, particularly those with limited technical capacity, are at risk of becoming dependent on a single vendor’s proprietary technology. This “lock-in” can lead to escalating costs over the long term, reduce the government’s flexibility to adapt the system to future needs, and limit data ownership and access. This risk is especially high in poorly designed public-private partnership (PPP) or build-operate-transfer (BOT) models where knowledge and capacity are not effectively transferred to the government. Mitigation strategies include the mandated use of open, international standards, strong and transparent procurement practices, and contractual requirements for knowledge transfer.

Part II: Navigating the Nexus of Technology and Policy: Regulatory Challenges

This part delves into the complex and rapidly evolving landscape of technology regulation, analyzing how governments are attempting to balance innovation with public interest in the critical domains of data privacy, AI, and social media.

Section 3: The Global Challenge of Data Privacy and Protection

As e-governance systems become increasingly data-intensive, the protection of personal data has emerged as a paramount regulatory challenge. The trust of citizens in digital government is directly linked to their confidence that their personal information will be handled responsibly and securely.

3.1 Foundational Principles of Modern Data Privacy Regulation

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has become the global gold standard for data privacy, and its core principles have been widely influential in shaping legislation around the world. The seven foundational principles, outlined in Article 5 of the GDPR, provide a robust framework for ethical data handling:

- Lawfulness, Fairness, and Transparency: Personal data must be processed lawfully, fairly, and in a transparent manner in relation to the data subject.

- Purpose Limitation: Data must be collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes.

- Data Minimization: The collection of personal data must be adequate, relevant, and limited to what is absolutely necessary in relation to the purposes for which it is processed.

- Accuracy: Personal data must be accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date.

- Storage Limitation: Data should be kept in a form which permits identification of data subjects for no longer than is necessary for the purposes for which the personal data are processed.

- Integrity and Confidentiality: Data must be processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security, including protection against unauthorized or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction, or damage, using appropriate technical or organizational measures (e.g., encryption).

- Accountability: The data controller is responsible for, and must be able to demonstrate compliance with, all of the above principles.

A key innovation of modern privacy regulation is the concept of “Privacy by Design and by Default”. This principle, enshrined in Article 25 of the GDPR, mandates that data protection considerations must be integrated into the design of any new system, product, or service from the very beginning, rather than being treated as a later addition. This means that privacy should be the default setting for any system, requiring a proactive approach to data protection that has profound implications for the architecture and development of all new e-governance platforms and services.

3.2 Comparative Analysis: The EU’s GDPR vs. Other Global Models

While the principles of data protection are gaining global consensus, the specific legal and regulatory approaches vary significantly across jurisdictions.

- The GDPR (European Union): The GDPR is a comprehensive, rights-based legal framework that establishes a single set of rules for data protection across the EU.

Its most significant feature is its broad extraterritorial scope; it applies to any organization, public or private, anywhere in the world, that processes the personal data of EU residents. It grants data subjects a wide range of enforceable rights, including the right of access, rectification, erasure (“the right to be forgotten”), and data portability. The regulation is enforced by independent Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) in each member state, who are empowered to levy substantial fines for non-compliance—up to €20 million or 4% of an organization’s global annual turnover, whichever is higher.

- The CCPA/CPRA (California, USA): The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), as amended by the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), represents the most significant data privacy legislation in the United States. Unlike the GDPR’s comprehensive approach, the US relies on a patchwork of federal sector-specific laws (e.g., for health and finance) and state-level legislation. The CCPA/CPRA is philosophically different from the GDPR; it is framed around consumer rights rather than fundamental human rights. It grants consumers the right to know what personal information is being collected about them, the right to delete that information, and, crucially, the right to opt-out of the “sale” or “sharing” of their personal information. A key distinction is its consent model: while the GDPR generally requires an explicit “opt-in” from users before their data can be processed, the CCPA operates on an “opt-out” basis, allowing data collection by default until a consumer actively objects.

- Other Global Models: Many countries have enacted or are developing their own data privacy laws, often drawing inspiration from the GDPR. Brazil’s Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados (LGPD) closely parallels the GDPR in its principles and scope. Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) is another established framework, highlighting the global trend towards codifying stronger data protection rights.

The influence of the GDPR extends far beyond the borders of the European Union, creating a phenomenon known as the “Brussels Effect.” Because of its stringent standards and extraterritorial reach, the GDPR has become the de facto global benchmark for data protection. Multinational corporations, to avoid the complexity of maintaining different compliance regimes, often adopt GDPR standards as their global policy. This, in turn, pressures public administration bodies worldwide to align their e-governance systems and data handling practices with GDPR principles. A government agency in any country wishing to share data with an EU counterpart, engage in cross-border digital trade, or even use a global cloud service provider that is subject to GDPR, will find it necessary to meet these high standards. This represents a powerful form of regulatory diffusion, where the legal framework of one region shapes the administrative practices of public sectors globally.

| Feature | GDPR (European Union) | CCPA/CPRA (California, USA) | LGPD (Brazil) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scope & Reach | Extraterritorial; applies to any entity processing data of EU residents, regardless of location. | Applies to for-profit businesses that meet certain revenue or data processing thresholds and “do business” in California. | Extraterritorial; applies to any processing of data of individuals in Brazil or data collected in Brazil. |

| Definition of Personal Data | Broad; “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person.” Includes online identifiers and pseudonymized data. | Broad; “information that identifies, relates to, describes, is reasonably capable of being associated with… a particular consumer or household”. | Very similar to GDPR; “information regarding an identified or identifiable natural person”. |

| Legal Basis for Processing | Requires one of six specific lawful bases (e.g., consent, contract, legitimate interest). | Not explicitly required in the same way; focus is on providing notice and opt-out rights. | Requires one of ten specific lawful bases, similar to GDPR. |

| Consent Requirement | Primarily “opt-in”; consent must be freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous. | Primarily “opt-out”; businesses can collect and process data by default but must provide a clear way for consumers to opt out of its sale/sharing. | Primarily “opt-in,” requiring free, informed, and unambiguous consent for a specific purpose. |

| Key Data Subject Rights | Access, rectification, erasure, restrict processing, data portability, object, rights re: automated decision-making. | Know/access, delete, opt-out of sale/sharing, non-discrimination, correct inaccurate information. | Access, rectification, erasure, data portability, information about sharing, revocation of consent. |

| Data Breach Notification | Mandatory notification to supervisory authority within 72 hours of becoming aware of the breach. | Notification to affected consumers required in the “most expedient time possible and without unreasonable delay”. | Mandatory notification to the national authority and data subjects in a “reasonable time period” if it may create risk or harm. |

| Enforcement & Penalties | Fines up to €20 million or 4% of global annual turnover, whichever is higher. | Civil penalties up to $2,500 per unintentional violation and $7,500 per intentional violation; statutory damages in data breach lawsuits. | Fines up to 2% of a company’s revenue in Brazil, capped at R$50 million per violation. |

3.3 Impact on E-Governance Design: Embedding “Privacy by Design” into Public Services

The rise of stringent data protection regulations has a direct and profound impact on the design and implementation of e-governance services. To be effective and trusted, digital government must be built on a foundation of robust data privacy.

The lack of data protection and privacy is a critical obstacle to e-government adoption. Citizens are often required to provide sensitive personal information to access digital public services, and concerns about how this data will be used, shared, and secured are a major source of hesitation. Studies show that trust in the government’s ability to protect data is a significant predictor of citizens’ intention to use e-government platforms. Therefore, governments have an obligation to provide full assurance of data protection to build the public confidence necessary for a successful digital transformation.

This necessitates a shift in how e-governance systems are designed. The principle of “Privacy by Design” requires that privacy considerations are no longer an afterthought but a core component of the development process. In practice, this means:

- Transparency: E-governance portals must have clear, accessible, and easily understandable privacy policies that explain what data is collected, for what purpose, how long it will be stored, and with whom it might be shared.

- Data Minimization: Systems should be engineered to collect only the data that is strictly necessary to provide a specific service, avoiding the unnecessary accumulation of personal information.

- User Control: Citizens must be given meaningful control over their data, including clear mechanisms for providing and withdrawing consent, accessing their information, and requesting corrections or deletions.

- Robust Security: Strong technical and organizational security measures, such as encryption and access controls, must be implemented to protect data from breaches.

The global nature of data flows means that even governments in countries without their own comprehensive privacy laws are influenced by regulations like the GDPR. To engage in international data sharing or utilize global technology platforms, adherence to these high standards often becomes a practical necessity, compelling a global uplift in the privacy standards embedded within e-governance systems.

Section 4: Governing Artificial Intelligence in the Public Sector

Artificial Intelligence (AI) represents the next frontier of digital government, offering the potential to revolutionize public administration. However, its power and complexity also introduce a new set of profound governance challenges that require novel regulatory approaches.

4.1 The Promise and Peril of AI in Government Operations

The potential benefits of deploying AI in the public sector are vast. AI can dramatically enhance efficiency by automating mundane and repetitive tasks, freeing up public servants for more complex work. It can improve the quality of decision-making by analyzing vast datasets to identify patterns and forecast future trends, helping to allocate resources more effectively. AI can also be used to tailor public services to the specific needs of individual citizens, detect fraud and anomalies in public spending, and create new opportunities for civic engagement. Practical use cases already being explored include using AI to manage traffic patterns in real-time, generate synthetic health data for research while protecting patient privacy, and optimize the delivery of public services.

However, these benefits are accompanied by significant and multifaceted risks. One of the most critical is the potential for algorithmic bias, where AI systems trained on historical data replicate and even amplify existing societal biases, leading to discriminatory and harmful outcomes for marginalized groups in areas like social benefit allocation, predictive policing, and public service access. The “black box” nature of some complex AI models creates a lack of transparency and explainability, making it difficult to hold the government accountable for AI-driven decisions.

Over-reliance on AI can erode public trust, widen existing digital divides, and propagate errors at scale if not managed properly.

4.2 Establishing Trustworthy AI: A Review of Global Governance Frameworks

In response to these challenges, a global discourse on AI governance has emerged, focused on creating frameworks to ensure that AI is developed and deployed in a manner that is ethical, transparent, and responsible.

- The OECD Framework: The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been a key international actor in this field. Its approach to trustworthy AI is built upon a framework that identifies seven key “enablers”—the foundational elements needed for effective AI adoption, including governance structures, data quality, digital infrastructure, skills, investment, procurement, and partnerships. These enablers are complemented by “guardrails”—the policies and oversight mechanisms that manage risks, such as transparency requirements, accountability measures, and independent oversight bodies.

- The EU AI Act: The European Union has taken a pioneering step by moving from principles to hard law with its AI Act. This landmark legislation establishes a comprehensive, risk-based regulatory framework. It categorizes AI systems into four tiers: unacceptable risk (which are banned, e.g., social scoring), high risk (e.g., in critical infrastructure or law enforcement, which are subject to strict requirements), limited risk (subject to transparency obligations), and minimal risk (unregulated). This approach represents the most assertive regulatory model globally, prioritizing safety and fundamental rights.

- The US Approach: In contrast, the United States has adopted a more decentralized, market-driven, and sector-specific approach. It relies on a combination of executive orders, voluntary standards developed by bodies like the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) with its AI Risk Management Framework, and enforcement by existing regulatory agencies within their respective domains (e.g., the FTC on consumer protection). This model prioritizes fostering innovation with less prescriptive, top-down regulation.

This divergence in regulatory philosophy—the EU’s precautionary, rights-based model versus the US’s innovation-focused, pro-market model, with Asia often pursuing state-guided strategies that balance rapid deployment with government oversight—creates a complex global landscape for AI governance.

Despite the development of these high-level national and international strategies, a significant public sector AI implementation gap has emerged. While governments are quick to announce ambitious AI policies, the on-the-ground capacity of public agencies to implement these technologies responsibly often lags far behind. The OECD’s own analysis reveals that many government AI initiatives remain stuck in the pilot phase, stymied by a lack of technical skills, poor data quality and governance, outdated legacy IT systems, and tight budgets. The primary barrier to public sector AI is not a lack of vision or regulatory ideas, but a fundamental deficit in the foundational “enablers” within the bureaucracy itself. This creates a risk that regulation will outpace implementation capacity, leading either to widespread non-compliance or a culture of risk aversion that stifles beneficial innovation.

4.3 Addressing Algorithmic Bias, Transparency, and Accountability

Three issues are central to the governance of AI in the public sector:

- Algorithmic Bias: This is a critical ethical and legal challenge. AI models trained on biased historical data will learn and perpetuate those biases. If an AI system is used to screen job applications or determine eligibility for social benefits based on past data that reflects systemic discrimination, it will produce discriminatory outcomes, harming already vulnerable populations. Mitigating bias requires systematic checks, audits, and the use of fairness-aware machine learning techniques throughout the AI lifecycle.

- Transparency and Explainability: For AI to be trustworthy, its decision-making processes must be understandable. This principle of transparency and explainability is a core tenet of AI governance. Public authorities must be able to explain why an AI system made a particular decision, especially when it affects an individual’s rights or access to services. This is essential for ensuring due process and allowing for meaningful oversight and accountability.

- Accountability: Clear lines of responsibility for the outcomes of AI systems must be established. This often requires maintaining a “human-in-the-loop” or “human-on-the-loop” for high-stakes decisions, ensuring that a human official retains ultimate responsibility and can override the AI’s recommendation. Accountability frameworks must define who is liable when an AI system causes harm—the developer, the government agency that deployed it, or the official who acted on its output.

Section 5: The State’s Role in the Digital Public Sphere: Regulating Social Media

The rise of social media platforms has created a new “digital public sphere” where much of modern political discourse takes place. This has presented governments with one of their most complex regulatory challenges: how to address the harms of misinformation and hate speech without infringing on the fundamental right to freedom of expression.

5.1 The Challenge of Misinformation and Harmful Content

Social media platforms have become a primary source of news and information for a majority of citizens, but their business models, which often prioritize engagement over accuracy, have also made them powerful vectors for the spread of mis- and disinformation. This “infodemic” can erode public trust in institutions, polarize societies, incite violence, and destabilize democratic processes, particularly during elections. A 2024 global poll conducted by IPSOS for UNESCO found that 85% of citizens are worried about the impact of online disinformation, and 87% believe it has already had a major impact on their country’s political life. While platforms have their own internal policies for content moderation, these are often applied inconsistently, lack transparency, and vary significantly from one platform to another, covering issues from election interference to manipulated media.

5.2 Regulatory Strategies: From Platform Self-Regulation to State Intervention

For years, the dominant governance model for social media was one of industry self-regulation. However, a growing consensus has emerged that this model is insufficient to address the scale of the problem, leading to increasing calls for state-led or co-regulatory intervention.

Several regulatory strategies are now being pursued globally. UNESCO has been a leading voice advocating for a multi-stakeholder approach that protects human rights. Its proposed framework calls for regulation that is grounded in international human rights standards and is based on principles of platform transparency, accountability, and robust human rights due diligence. This includes requirements for platforms to have qualified moderators, be transparent about their algorithms and moderation processes, and establish independent oversight mechanisms.

Legislative action is also gaining momentum. The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) is a landmark piece of legislation that moves beyond self-regulation by imposing legally binding obligations on online platforms to mitigate systemic risks, such as the spread of disinformation and illegal content. It requires large platforms to conduct risk assessments, be more transparent about their content moderation and recommendation algorithms, and allow for independent audits.

The regulation of social media starkly illustrates a fundamental sovereignty mismatch in the digital age. The platforms themselves are global and borderless, operating under a single set of community standards, while the legal and regulatory authority of governments is bound by national territory. A user in Germany is subject to German law, but the platform they use, such as YouTube or Facebook, is headquartered in the US and operates under its own global rules. This mismatch makes unilateral action by any single state largely ineffective. It forces an evolution in governance away from traditional state-centric regulation and towards complex, multi-stakeholder, and transnational cooperative models. As UNESCO’s work suggests, the only viable path forward involves creating networks of independent regulators and developing shared international standards to ensure that global platforms are accountable to all the communities they serve.

5.3 Protecting Democratic Processes and Freedom of Expression

The central dilemma in regulating the digital public sphere is striking the right balance between countering harmful content and protecting the fundamental right to freedom of expression. International human rights law, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), permits restrictions on speech only under very strict conditions; they must be provided by law, pursue a legitimate aim, and be necessary and proportionate. Overly broad or vague regulations risk being used by governments to suppress dissent and silence critical voices.

Therefore, regulatory efforts must be narrowly tailored to address specific, well-defined harms. This is particularly crucial for protecting the integrity of electoral processes.

Specific measures being advocated include requiring platforms to conduct electoral risk assessments, clearly label all political advertising and provide transparency on its targeting, and actively combat content aimed at suppressing voter turnout.

A complementary strategy is to focus not just on removing harmful content, but also on actively promoting trusted, high-quality information. This involves regulatory measures to ensure that public service media and independent, fact-based journalism are given greater prominence and visibility on digital platforms, providing citizens with reliable alternatives to misinformation.

Part III: Fostering Innovation and Participation: Open Data and Civic Tech

This part explores the proactive side of GovTech, focusing on how governments can leverage technology and data not just to administer, but to innovate, empower citizens, and foster a more collaborative and transparent democracy.

Section 6: Open Government Data as a Catalyst for Innovation

Open Government Data (OGD) is a movement and a policy based on the premise that certain data should be freely available to everyone to use and republish as they wish, without restrictions from copyright, patents, or other mechanisms of control. When governments adopt this philosophy, they can unlock significant economic and social value.

6.1 The Core Principles of Open Government Data (OGD)

For government data to be truly “open” and useful, it must adhere to a set of internationally recognized principles. These principles ensure that the data is not just technically public but is genuinely accessible and usable for a wide range of purposes:

- Complete: All public data should be made available, not just a curated subset.

- Primary: Data should be published in its raw, original form (as collected at the source), with the highest possible level of granularity, not in aggregated or modified forms.

- Timely: Data should be released as quickly as necessary to preserve its value.

- Accessible: Data must be available to the widest range of users for the widest range of purposes, without requiring registration.

- Machine-Processable: Data must be published in structured, machine-readable formats (e.g., CSV, JSON, XML) that allow for automated processing, rather than in non-structured formats like PDF.

- Non-discriminatory: Data should be available to anyone, with no group or person having exclusive access.

- Non-proprietary: Data must be available in a format over which no single entity has exclusive control, avoiding reliance on proprietary software.

- License-free: Data should be explicitly placed in the public domain, free of copyright, patent, or trademark restrictions, to permit maximum reuse.

6.2 Unlocking Economic and Social Value: Case Studies in Growth and Public Good

The release of OGD has been shown to be a powerful catalyst for both economic innovation and social progress.

Economic Impact

A landmark 2013 report by the McKinsey Global Institute estimated that open data could help create over $3 trillion in additional value annually across seven domains of the global economy. This value is generated through the creation of new data-driven products and services, increased operational efficiencies in existing businesses, and greater market transparency. Subsequent analysis suggests the boost to GDP from broad adoption of open-data ecosystems could be as high as 1.5% in the EU and the US, and up to 5% in India by 2030.

Concrete case studies illustrate this economic potential:

- In Denmark, the decision to make the national address dataset open and free generated direct economic benefits of €62 million between 2005 and 2009, a massive return on the €2 million investment required to open the data. This has been particularly valuable for logistics and service industries.

- In the United Kingdom, the Open Banking initiative mandated that major banks share customer data (with consent) via secure APIs. This has fueled a vibrant financial technology (Fintech) sector, with startups creating new services for budgeting, lending, and mortgage applications.

- In India, the use of the Aadhaar digital ID system for “Know Your Customer” (KYC) verification in the financial sector reportedly reduced the cost for institutions from approximately $5 per customer to just $0.70, creating massive efficiency gains.

- The release of GPS data by the U.S. government, once a military-only technology, created a global public utility that now underpins countless industries, from ride-sharing and logistics to precision agriculture.

Social Impact and Improved Governance

Beyond its economic benefits, OGD is a critical tool for improving governance and creating social value. By making government operations more transparent, OGD enhances public accountability and serves as a powerful tool to combat corruption. It also enables better, data-driven public services and more effective crisis response.

- In Puerto Rico, following the devastation of Hurricanes Irma and Maria, federal agencies used open data initiatives to improve imperfect address data, which was hampering emergency response and relief efforts.

- In Nepal, after the 2015 earthquake, open data platforms were used to coordinate disaster relief and recovery, demonstrating the critical role of timely data sharing in a crisis.

- The National Broadband Map in the U.S. is an example of using open data and crowdsourcing to increase transparency and public engagement in a key national policy area, allowing citizens to verify and challenge data on internet service availability.

6.3 From Data Publication to Usable Ecosystems: Building Platforms for Impact

Early efforts in the OGD movement were often guided by a “publish and they will come” philosophy. Governments focused on the technical task of launching open data portals and populating them with datasets. However, experience has shown that this approach is often ineffective. Many of these portals saw little use because the data was of poor quality, poorly documented, or irrelevant to public needs. This led to the realization that simply publishing data is not enough; value is only created when that data is actively used.

This understanding has led to a crucial strategic shift. The value of open government data is not realized at the point of publication by the government (the supply side) but at the point of innovative reuse by external actors like entrepreneurs, researchers, and citizens (the demand side). Therefore, the most effective OGD strategies are those that move beyond simply increasing the supply of datasets to actively cultivating a demand-side ecosystem. This involves designing platforms for use, not just for compliance.

Key features of a use-oriented OGD platform include:

- User-Friendly Interfaces: Intuitive navigation, powerful search functions, and clear data descriptions are essential to lower the barrier to entry for non-technical users.

- Built-in Visualization Tools: Platforms should include tools for creating charts, maps, and dashboards directly on the site, allowing users to quickly explore and understand the data without needing specialized software.

- Robust APIs (Application Programming Interfaces): APIs are critical for enabling developers to build applications and services directly on top of government data, fostering an ecosystem of innovation.

- Fostering Communities of Practice: Successful OGD initiatives actively engage with and support the communities that use their data. This includes collaboration with civic tech groups, journalists, academics, and startups through events like hackathons and data jams.

By focusing on the needs of data users and actively fostering an ecosystem around them, governments can transform their open data portals from static repositories into dynamic engines of civic engagement and economic innovation.

Section 7: Civic Technology and the Future of Citizen Engagement

Civic technology, or “civic tech,” represents a grassroots, citizen-driven approach to using technology to improve society and governance. It is a complementary force to government-led GovTech initiatives, often leveraging open government data to build tools that empower citizens and foster a more participatory democracy.

7.1 Defining the Civic Tech Landscape: Tools for Participation and Community Action

Civic tech is broadly defined as the use of technology to enhance the relationship between people and government. While GovTech is primarily focused on improving the internal efficiency and service delivery of public institutions, civic tech is focused on empowering citizens to engage more effectively with those institutions. The two are symbiotic: effective GovTech can provide the data and platforms (like APIs) that civic tech needs to thrive, while a vibrant civic tech ecosystem can provide valuable feedback and innovative solutions that make government more responsive.

The civic tech landscape is diverse, encompassing a wide spectrum of tools and platforms that can be broadly categorized into two main areas:

- Open Government Tools: These are technologies that aim to make government more transparent and participatory. Examples include:

- Data Access and Transparency Portals: Platforms that make government data accessible and understandable.

- E-Petition and Public Consultation Platforms: Websites that allow citizens to propose and support policy ideas or provide feedback on government initiatives.

- Participatory Budgeting Tools: Platforms that enable residents to decide how to allocate a portion of a public budget.

- Resident Feedback Apps: Mobile applications that allow citizens to report local issues like potholes, broken streetlights, or illegal dumping directly to their municipality.

- 2.

Community Action Tools:

These are technologies that facilitate collaboration and problem-solving among citizens at the local level. Examples include:

- Neighborhood Forums and Mutual Aid Networks: Platforms that connect neighbors to share information, resources, and support.

- Civic Crowdfunding: Websites that allow communities to collectively fund local projects, such as a new playground or a community garden.

- Information Crowdsourcing: Tools that enable citizens to collectively gather and map information, such as mapping accessibility features in a city.

7.2 Measuring the Impact: Assessing Civic Tech’s Effect on Government Responsiveness

Quantifying the impact of civic tech is a significant methodological challenge. Early assessments often relied on simple output metrics like the number of app downloads or active users. However, measuring true impact requires moving beyond these vanity metrics to track on-the-ground outcomes, such as changes in government policy, improvements in service delivery, or shifts in civic behavior.

Despite these challenges, a growing body of empirical evidence demonstrates the potential of civic tech to enhance government responsiveness. A large-scale, cross-country study by the World Bank covering 176 nations found a significant and positive correlation between the presence of GovTech platforms for citizen participation and higher levels of citizen engagement. The study also found that these platforms are more effective in high-income economies and in countries with already efficient and stable governments.

Case studies provide concrete examples of impact:

- In Kenya, the MajiVoice platform was created to allow citizens to report complaints about water and sanitation services. Following its implementation, the number of complaints received surged from 400 to 4,000 per month, and more importantly, the resolution rate for these complaints increased dramatically from 46% to 94%, demonstrating a clear improvement in government responsiveness.

- In Pakistan, the government-developed “Pakistan Citizens’ Portal” mobile app has become a major channel for complaint management, with over 5 million users and more than 4.6 million complaints addressed since its launch.

- In Indonesia, the Opentender platform, a collaboration between government and civic tech communities, uses open data to facilitate transparency in public procurement and allow for citizen oversight.

However, the impact of civic tech is not always guaranteed. A comprehensive meta-analysis of ICT-enabled citizen voice initiatives in the Global South introduced a crucial conceptual distinction between “yelp” (the ability of citizens to express their voice) and “teeth” (the power to elicit a response from the state). The study found that while technology platforms have been highly effective at increasing citizens’ capacity to “yelp,” they have been far less successful at ensuring that this voice has “teeth.” The analysis concluded that while these platforms increased policymakers’ capacity to respond to citizen feedback, they had yet to consistently influence their willingness to do so.

This points to a fundamental “last mile” problem in civic tech. Technology is incredibly effective at solving the “input” problem—gathering, aggregating, and structuring citizen feedback at a scale never before possible. However, it cannot, by itself, solve the “output” problem of bureaucratic inertia, lack of resources, or political indifference within government. The ultimate impact of civic tech, therefore, depends not just on the quality of the technology but on the institutional capacity and political will of the government to listen and respond. Civic tech is a powerful tool for enhancing communication, but it is not a panacea for poor governance.

7.3 Synergies in Action: How Open Data Fuels Civic Tech Applications

Open government data is the essential raw material that fuels much of the civic tech ecosystem. The availability of reliable, machine-readable data via government APIs allows developers, non-profits, and engaged citizens to build a vast array of applications and tools that create public value.

Examples of this powerful synergy are abundant:

- Transportation: The Transit App, used in hundreds of cities worldwide, is a prime example. It aggregates open transportation data from various public transit agencies to provide users with real-time, multi-modal trip planning. Without open, standardized transit data feeds, such an application would be impossible to build and scale.

- Public Health and Environment: In Toronto, the Beaches Water Quality app uses open data on E. coli testing from Toronto Public Health to provide real-time notifications to swimmers about water safety. In Chicago, a civic tech volunteer group, Chi Hack Night, used open data to build a predictive analytics tool to track E. coli levels in Lake Michigan, which was eventually adopted by the city.

- Government Accountability: The Citizen Police Data Project in Chicago, created by the Invisible Institute, combines open geographic data with police misconduct records obtained through Freedom of Information requests to create a public database for tracking police accountability.

- Civic Information: The Represent API is an open-source tool that allows users to input their location and instantly find their elected officials and electoral districts, powered by open government data on political boundaries and representatives.

These examples demonstrate a clear value chain: governments release primary data, and the civic tech community acts as an intermediary, transforming that raw data into user-friendly applications and services that directly benefit the public.

Part IV: Overarching Challenges in Digital Governance

This part synthesizes the critical, cross-cutting challenges that affect all aspects of GovTech, from service delivery and regulation to citizen participation. These are the systemic issues that must be addressed for digital transformation to be successful and equitable.

Section 8: Bridging the Digital Divide: Ensuring Inclusive Transformation

The promise of e-governance—to make public services more accessible and democracy more participatory—is fundamentally threatened by the persistence of the digital divide. This divide is not a single gap but a multi-faceted phenomenon that creates significant barriers to inclusive digital transformation.

Defining the Divide

The digital divide is most commonly understood as the gap between those who have meaningful access to digital technologies and those who do not. This is a major hurdle for the adoption of e-governance, particularly in developing countries where disparities are most acute. However, the concept extends beyond mere access to infrastructure. It also encompasses gaps in:

- Affordability: The high cost of internet service and internet-enabled devices can be prohibitive for low-income households. In South Asia, for example, a staggering 61% of the population lives within range of a mobile network but does not use the internet, largely due to affordability and other barriers.

- Digital Literacy: The skills and knowledge required to confidently and effectively use digital tools are not evenly distributed. A lack of digital literacy can prevent individuals from taking advantage of online services, even when access is available.

- Relevance and Design: Services that are not designed with user needs in mind or are not available in local languages can also create barriers to adoption.

These disparities disproportionately affect already marginalized communities, including those in rural and remote areas, women, the elderly, persons with disabilities, and ethnic and linguistic minorities.

Impact on Governance

The digital divide has profound implications for governance. When public services are moved exclusively online, it risks creating a two-tiered system of citizenship, where those with digital access and skills can easily interact with the state, while those without are left behind, potentially cut off from essential services and democratic processes. Online public consultations, e-voting, and other forms of e-participation become inaccessible to large segments of the population, undermining the goal of inclusive governance and potentially widening existing social and economic inequalities. The divide also intersects with trust; those who are unfamiliar or uncomfortable with digital tools may inherently distrust e-services, further depressing adoption rates.

The Algorithmic Divide

As governments increasingly turn to AI and automated decision-making, a new and more insidious form of inequality is emerging: the algorithmic divide. This refers to the gap between those who understand, have access to, and can influence the design and deployment of algorithmic systems, and those who are merely subject to their decisions. This emerging divide threatens to create new forms of exclusion in political, social, and economic life, where opportunities are allocated by opaque systems that are beyond the comprehension or control of ordinary citizens.

Section 9: Surveillance, Security, and Public Trust in the Digital Age

The digital transformation of government, while offering immense benefits, also introduces significant risks related to cybersecurity, state surveillance, and the erosion of public trust. These challenges are deeply intertwined and represent a fundamental tension in the architecture of the digital state.

Cybersecurity Threats

As governments collect and centralize vast amounts of sensitive citizen data to power e-governance services and digital ID systems, they create high-value targets for malicious actors.

Cybersecurity is therefore a pervasive and critical challenge for all digital government initiatives. Data breaches of government servers, such as the incidents experienced in Nepal, can have devastating consequences, exposing citizens’ personal information, undermining national security, and severely damaging public confidence in the state’s ability to manage its digital infrastructure.

Risks of State Surveillance

The same technologies that enable efficient and personalized public services can also be repurposed as tools for mass surveillance and social control. This dual-use nature is a central ethical dilemma of GovTech. National digital ID programs, which can link biometric data to a wide range of government and private sector transactions, create the potential for a comprehensive surveillance architecture. AI-driven systems used for predictive policing or social welfare fraud detection can lead to pervasive monitoring and discriminatory targeting of certain populations. Social media platforms can be used by governments to monitor public discourse and identify dissidents. In some countries, vague and oppressive laws passed under the guise of “national security” have been used to justify widespread surveillance and undermine digital rights.

Erosion of Public Trust

Public trust is the currency of e-governance. Without it, even the most technologically advanced systems will fail due to low adoption rates. The perceived risks of data breaches, the misuse of personal information by the government, and a general lack of transparency can severely undermine citizens’ willingness to engage with digital government services. Building and maintaining this trust requires a demonstrated commitment to data protection, robust security, transparency in how data is used, and meaningful accountability mechanisms for when things go wrong.

Section 10: The Evolving Discourse on Digital Rights and Sovereignty

The governance of technology is not just a domestic policy issue; it is a central theme in modern geopolitics. The concept of “digital sovereignty” has emerged as a key framework through which states are attempting to assert control over the digital environment, leading to a complex and often contentious global discourse.

Defining Digital Sovereignty

Digital sovereignty refers to the ability of a state or region to exercise authority over its own digital infrastructure, data, and technological development, while protecting the rights and interests of its citizens in a globalized digital ecosystem. It is an extension of the traditional concept of state sovereignty into the digital realm and has become a central point of competition among global powers.

Competing Global Models

Three distinct models of digital sovereignty have emerged, each reflecting a different political and economic philosophy:

- The European Union Model: The EU pursues a rights-based and regulatory approach to digital sovereignty. It uses comprehensive legislation like the GDPR and the AI Act as tools to project its values globally, aiming to create a digital single market that is independent of non-EU technology companies and that guarantees the fundamental rights of its citizens.

- The United States Model: The U.S. has traditionally favored a market-driven, laissez-faire approach that promotes innovation and the free flow of data. This model leverages the global dominance of its major technology companies and advocates for a multi-stakeholder model of internet governance rather than state-led control.

- The Chinese Model: China has implemented a state-centric model of “cyber sovereignty,” which emphasizes strict state control over the internet and digital infrastructure. This approach involves extensive internet regulations, data localization requirements, and the promotion of domestic technology champions to minimize external influence.

Digital Colonialism and the Global South

This geopolitical competition has profound implications for developing countries. Many nations in the Global South find themselves as “rule-takers” in a digital world whose standards and architectures are defined by these major powers. This has given rise to the concept of “digital colonialism,” which argues that the concentration of data, capital, and digital infrastructure in the hands of a few powerful states and corporations creates new forms of economic exploitation and political subordination. In this view, developing countries risk having their data extracted and monetized by foreign platforms without receiving the economic benefits, while their own capacity for digital innovation is stifled.

The challenges of the digital divide, state surveillance, and the struggle for digital sovereignty are not isolated issues but are deeply interconnected crises of digital inequality. A government’s strategy for digital transformation must be three-dimensional to be successful. A nation that focuses only on asserting external digital sovereignty (e.g., by building its own data centers) without addressing its internal digital divide risks creating a technologically advanced state that serves only its elite, leaving the most vulnerable citizens behind. Conversely, a nation that focuses only on bridging the internal divide (e.g., by promoting access to global platforms) without a strategy for sovereignty may create a fully connected populace that is subject to the data extraction, surveillance, and governance regimes of foreign powers. Therefore, a truly successful and equitable digital governance strategy must simultaneously promote inclusive internal access, protect citizen rights from all forms of surveillance (both domestic and foreign), and build national capacity to govern effectively in the global digital ecosystem.

Part V: The Next Frontier: Emerging Technologies and Strategic Recommendations

This final part looks to the future, assessing the potential impact of next-generation technologies on governance and providing a consolidated set of strategic recommendations for policymakers and public administrators.

Section 11: Future Horizons: Blockchain, Quantum Computing, and the Metaverse in Governance

The current wave of digital transformation is only the beginning. A new generation of disruptive technologies is on the horizon, each with the potential to fundamentally reshape the landscape of public administration and governance.

- Blockchain Technology: Blockchain, or distributed ledger technology, offers a new model for trust and security based on decentralization and cryptographic verification. Its potential applications in governance are significant. It can be used to create transparent and tamper-proof records for land registries, supply chains, and public procurement, thereby reducing corruption. In the realm of democratic participation, blockchain could enable more secure and verifiable online voting systems. The tokenization of real-world assets on a blockchain could also create new efficiencies in how public assets are managed and traded. The core governance implication of blockchain is its ability to facilitate trusted transactions and agreements without relying on a central intermediary, which could transform many traditional functions of the state.

- Quantum Computing: Quantum computers operate on the principles of quantum mechanics, allowing them to solve certain types of problems that are intractable for even the most powerful classical supercomputers. For governance, this has a dual-edged potential. On the one hand, quantum computing could be used to solve complex optimization problems, such as optimizing national logistics, managing energy grids, or modeling climate change with unprecedented accuracy, leading to better policy decisions. It could also enable the creation of a perfectly secure “quantum internet”. On the other hand, quantum computing poses a profound threat to national and global security. A sufficiently powerful quantum computer will be able to break most of the public-key encryption standards that currently protect virtually all secure digital communication, from financial transactions to classified government data. This creates an urgent need for governments to develop and transition to “post-quantum cryptography” and to establish proactive governance frameworks to manage this disruptive technological shift.

- The Metaverse: The metaverse refers to the concept of persistent, shared, 3D virtual spaces linked into a perceived virtual universe. While still in its early stages, its potential implications for governance are far-reaching. Governments could provide immersive digital public services, where citizens interact with officials via avatars in virtual government offices. Public consultations and civic engagement could take place in shared virtual environments. Urban planners could use “digital twins“—highly detailed virtual models of cities—to simulate the impact of new infrastructure projects or policies. However, the metaverse also presents immense new governance challenges, raising complex questions about jurisdiction, law enforcement, data privacy, and economic regulation in virtual worlds that transcend physical borders. It will require entirely new models of governance that extend far beyond those currently applied to the internet.

Section 12: Strategic Recommendations for Policymakers and Public Administrators

Navigating the complexities of the digital transformation requires a strategic, forward-looking, and principled approach. Based on the comprehensive analysis presented in this report, the following recommendations are offered to guide policymakers and public administrators in building a more effective, inclusive, and accountable digital state.

1.

Adopt a Holistic, “Whole-of-Government” Approach

Digital transformation cannot succeed as a series of isolated IT projects confined to departmental silos. It requires a “whole-of-government” strategy with strong, high-level political commitment and a clear institutional mandate for coordination. This involves breaking down inter-agency barriers to data sharing and creating integrated, citizen-centric services that provide a seamless user experience.

Prioritize Inclusivity and Bridge the Digital Divide

The primary goal of digital government should be to serve all citizens, not just the digitally savvy. Governments must move beyond simply providing online services and make proactive, sustained investments in bridging the digital divide. This includes initiatives to improve the affordability of internet access and devices, nationwide digital literacy programs, and ensuring that all digital services are accessible to people with disabilities. Crucially, non-digital service channels must be maintained and strengthened to ensure that no one is left behind.

Embed Rights and Ethics by Design