Viral Growth Mechanics: Engineering Exponential Product Spread

Section 1: Introduction: Deconstructing the Engine of Viral Growth

In the lexicon of modern business, few terms are as coveted or as misunderstood as “virality.” Often mistaken for a stroke of luck or an unpredictable cultural phenomenon, true virality is neither. It is an engineered outcome, the result of a meticulously designed and quantitatively managed system that transforms a product’s user base into its primary acquisition channel. This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the mechanics that power this engine of growth. It moves beyond superficial definitions to deconstruct the core components of viral systems: the self-perpetuating viral loop, the quantitative measure of its output known as the K-factor, and the psychological and economic levers of invite incentives. By examining the theoretical frameworks, practical applications, and strategic pitfalls of virality, this analysis serves as a strategic guide for product leaders, marketers, and founders seeking to build sustainable, exponential growth into the very fabric of their products.

Defining Virality as an Engineered Growth Mechanism

Virality is the tendency of a product, service, or piece of content to spread rapidly and exponentially from person to person through user-driven sharing and word-of-mouth. This process is analogous to the epidemiological spread of a virus, where each “infected” individual passes the “infection” to new hosts, creating a compounding growth curve. However, unlike a biological event, product virality is not an accident. It is the deliberate result of “very careful branding, positioning, and execution”.

The fundamental mechanism of virality is the integration of sharing into the core user experience. It occurs when existing users naturally and functionally promote a product while using it, thereby creating self-perpetuating growth cycles. This is a critical distinction from traditional marketing. In a paid acquisition model, a company pays for each new user through advertising. In a viral model, the product’s own users become the acquisition channel, driving compounding growth at a significantly lower, and often near-zero, marginal cost. This dynamic dramatically reduces customer acquisition costs (CAC), rapidly increases brand awareness, and builds a foundation of trust through peer-to-peer recommendations.

The most powerful and defensible form of virality is not an ancillary marketing campaign but a core product feature. When sharing is integral to deriving value from the product, the growth engine becomes intrinsic to its function. For example, a user must share a Zoom meeting link for the product to fulfill its purpose; in doing so, they expose the product to non-users and initiate a new acquisition cycle. This perspective reframes virality from a marketing task to a fundamental product design challenge, one that should be considered from the earliest stages of development rather than as a post-launch marketing initiative.

Distinguishing Virality from Word-of-Mouth and Network Effects

To strategically engineer virality, it is essential to first establish precise definitions and distinguish it from two related but distinct concepts: word-of-mouth (WOM) and network effects. Conflating these terms leads to flawed strategies and misaligned expectations.

Virality vs. Word-of-Mouth (WOM): While both involve user-driven promotion, their mechanisms differ. WOM occurs when customers are so highly satisfied with or “enamored” by a product that they naturally talk about it in their daily lives. It is a byproduct of an exceptional customer experience. Virality, conversely, is an engineered process where sharing is a functional part of using the product itself. As stated in the book Viral Loop, “Word of mouth is powerful, but viral marketing is like putting it on steroids”. A user recommending their Tesla is WOM; a user sharing a Dropbox folder, which requires the recipient to sign up to access it, is virality.

Virality vs. Network Effects: This is a more nuanced but critical distinction. Virality is a growth mechanism focused on the speed and efficiency of user acquisition. A product is viral if its rate of adoption increases with adoption. Network effects, on the other hand, are a value and defensibility mechanism focused on user retention. A product has network effects if its value to each user increases as more users join the network.

These two concepts are not mutually inclusive. A viral product does not necessarily have network effects; for example, a popular mobile game may spread rapidly through social sharing but does not become inherently more valuable to a player just because more people are playing it. Conversely, a product with strong network effects may not be viral; B2B marketplaces, for instance, derive immense value from having more buyers and sellers but often rely on traditional sales or paid marketing to acquire them.

However, when these two forces work in concert, they can create a powerful and defensible growth flywheel. A viral mechanism can be used to rapidly acquire the critical mass of users necessary for a network effect to activate. Once the network effect takes hold, the increased value of the product strengthens the intrinsic motivation for users to invite others, making the viral loop more efficient and creating a formidable competitive moat. PayPal’s aggressive early referral program is a classic example of using a high-cost viral strategy as a short-term investment to kickstart a long-term, defensible network effect in the payments space.

| Characteristic | Virality | Word-of-Mouth (WOM) | Network Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | User Acquisition (Growth) | Brand Affinity & Advocacy | User Retention (Value & Defensibility) |

| Core Mechanism | Sharing as an integral function of product usage | Sharing driven by high customer satisfaction | Product value increases as more users join |

| Primary Driver | Intrinsic or extrinsic incentives built into the product | Exceptional customer experience and delight | Increased utility, access, or liquidity |

| Growth Pattern | Potentially exponential and self-sustaining | Linear or organic | Compounding value leading to a competitive moat |

| Classic Example | Dropbox (sharing files), Zoom (meeting invites) | Tesla (owner enthusiasm), Apple (brand loyalty) | Facebook (social graph), Telephone (communication) |

Overview of the Core Components: The Viral Loop, K-Factor, and Incentives

The engine of virality is composed of three interconnected systems, which form the structure of this report:

- The Viral Loop: This is the mechanical process that powers growth. It is the cyclical, repeatable series of steps a user takes to discover a product, experience its value, and share it with others, who then begin the cycle anew. Understanding this loop is fundamental to engineering virality.

- The K-Factor: This is the primary performance metric of the viral engine. It is a mathematical coefficient that quantifies the number of new users generated by each existing user, providing a clear measure of a product’s viral potential.

- Incentives: This is the fuel for the engine. Incentives are the rewards—whether psychological, social, or economic—that motivate users to initiate and perpetuate the viral loop, overcoming inertia and friction in the sharing process.

By dissecting each of these components in detail, it becomes possible to move from hoping for virality to systematically designing, measuring, and optimizing for it.

Section 2: The Viral Loop: Engineering a Self-Sustaining Growth Cycle

The viral loop is the foundational mechanism of viral growth. It is a self-reinforcing, closed system where the output of one cycle—a new user—becomes the input for the next, leading to compounding growth. Unlike a traditional marketing funnel, which is linear and requires constant refilling from the top, a viral loop is cyclical and can become self-sustaining. Engineering a successful viral loop requires a deep understanding of its core stages and, most critically, the speed at which it operates.

Anatomy of a Viral Loop

A viral loop is a chain reaction that consists of a series of clearly defined stages or actions. While the specifics may vary by product, the fundamental process remains consistent. It begins with user acquisition and culminates in the acquisition of more users, who then repeat the process.

The key stages of a viral loop are:

- 1. Acquisition & Trigger: The loop begins when a new user discovers and signs up for the product. This can occur through organic discovery, paid marketing, or, ideally, as the result of a previous viral loop. Shortly after joining, the user encounters a “trigger”—a prompt or opportunity to share the product. This trigger is most effective when presented at a “magic moment” of high engagement, such as during onboarding or immediately after the user has experienced the product’s core value for the first time.

- 2. Activation & Action: The user becomes “activated” by experiencing the product’s “aha moment”—the point at which they understand and derive utility from it. This positive experience motivates them to take a specific action that shares the product with non-users. For the loop to be effective, this action must be as simple and frictionless as possible.

- 3. Sharing & Invitation: The user’s action generates an output, known as the “viral carrier,” which is shared with their external network. This carrier can take many forms: a direct invitation to join a platform, a shared piece of content created with the product (e.g., a design from Canva), a watermarked image or video, an embedded widget, or a report of results or achievements.

Conversion & Response: A recipient in the external network sees the viral carrier, is intrigued by its value proposition, clicks through, and converts into a new user of the product. This new user now enters the loop at the first stage, ready to be activated and become a referrer themselves, thus perpetuating the cycle.

The Critical Role of Viral Cycle Time

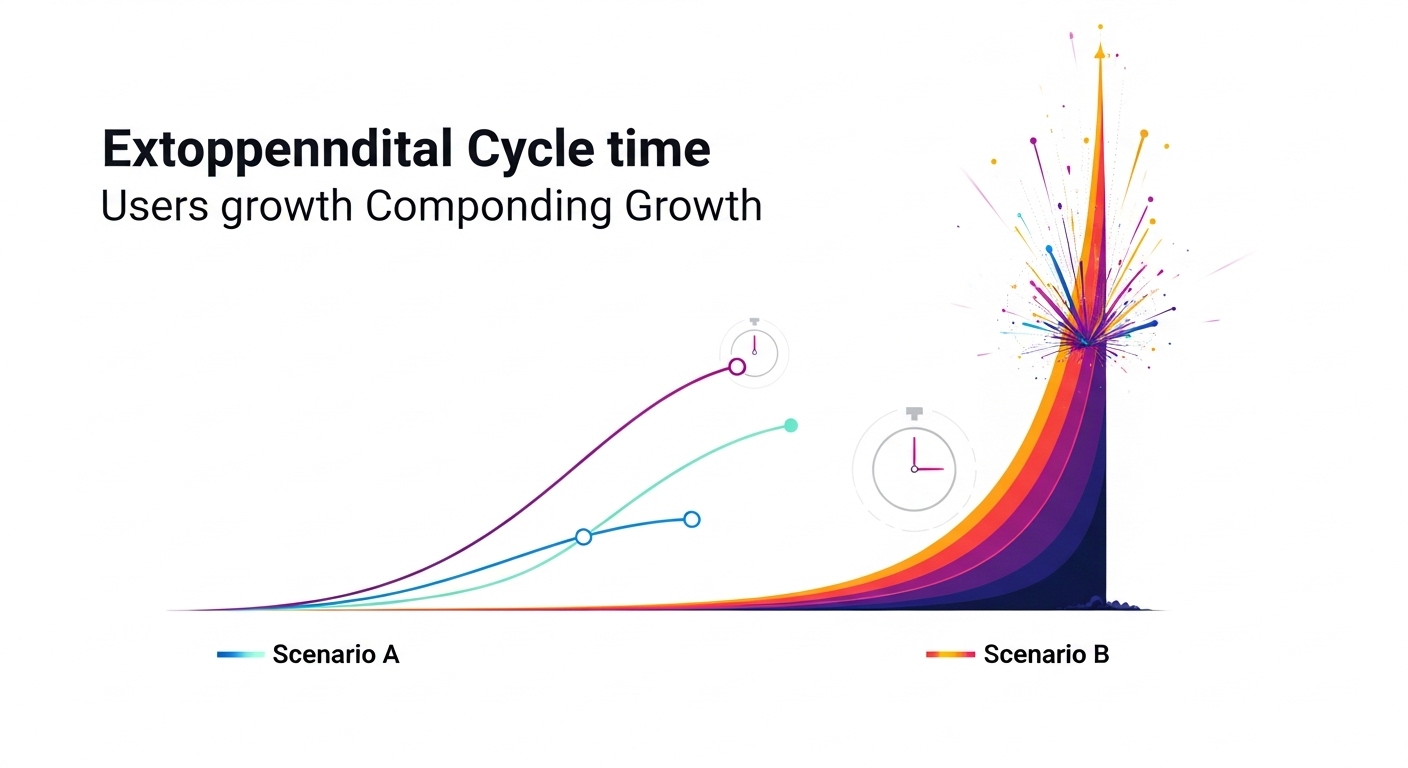

While the structure of the viral loop defines the path of viral growth, the Viral Cycle Time (CT) defines its speed. Viral Cycle Time is the median time it takes for one full loop to complete: from the moment a new user signs up to the moment their first successful referral also signs up. This metric is arguably more critical to achieving exponential growth than any other single variable.

The power of cycle time lies in the mathematics of compounding. A shorter cycle time means more growth loops can execute within a given period, and since each loop compounds on the last, the effect on user growth is exponential. The number of cycles that can run is an exponent in the viral growth formula, typically represented as , where is the time period and is the cycle time. Because of this exponential relationship, reducing the cycle time has a far more dramatic impact on growth than proportionally increasing the number of referrals per user (the K-factor), particularly once a product has achieved a K-factor greater than 1.

To illustrate this, consider a product starting with 10 users where each user, on average, successfully refers 2 new users.

- Scenario A (CT = 2 days): After 20 days, 10 cycles have completed. The user base would grow to approximately 20,470 users.

- Scenario B (CT = 1 day): After 20 days, 20 cycles have completed. By simply halving the cycle time, the user base would explode to over 20 million users.

This dramatic difference highlights that the frequency of compounding is a massive lever for growth. A viral loop that takes two months to complete is significantly less valuable than one that takes two weeks, even if the former has a higher K-factor.

However, this powerful engine is highly sensitive to user retention. A high churn rate acts as a major drag on the system, effectively nullifying any optimizations made to the cycle time. If users churn before they have a chance to complete a single viral loop, the speed of that loop becomes irrelevant. Analysis suggests that viral cycle time only becomes a meaningful growth lever when the churn rate is below approximately 15%; if churn is too high, the “leaky bucket” problem prevents the compounding effect from ever taking hold. This establishes a clear strategic hierarchy: a business must first solve for product value and retention before investing heavily in accelerating its viral cycle.

Strategies for Optimizing and Shortening Cycle Time

Optimizing Viral Cycle Time is fundamentally about accelerating a user’s journey from initial sign-up to their “aha moment” and subsequent share. It is a core product management challenge, not just a superficial marketing tactic. Strategies include:

- Streamline Onboarding: The most critical lever is a smooth, intuitive, and efficient onboarding process that guides the user to the product’s core value as quickly as possible. The goal is to minimize both “time to value” and “time to sharing”. This can involve interactive tutorials, pre-built templates, or a guided first-use experience.

- Reduce Sharing Friction: The act of sharing must be seamless. This can be achieved with one-click sharing buttons, pre-populated and customizable invitation messages, and direct integrations with the social and messaging platforms where the user’s network resides.

- Leverage High-Engagement Touchpoints: Instead of generic or disruptive prompts, invitations to share should be contextually placed at moments of peak user satisfaction and excitement. This could be immediately after a successful interaction, upon reaching a performance milestone, or when a user experiences the product’s “magic moment” for the first time.

- Design for Inherent Virality: For certain product categories, the cycle time is naturally short because sharing is a prerequisite for value. Collaboration tools (e.g., Figma, Slack), communication apps (e.g., WhatsApp), and social networks (e.g., Facebook) have inherently short cycle times because their core function involves inviting and interacting with others. Designing a product where the core use case itself is the viral loop is the most powerful way to ensure a short cycle time.

Quantifying Virality: A Deep Dive into the K-Factor

While the viral loop describes the qualitative process of user-driven growth, the K-factor provides the quantitative measure of its effectiveness. It is the single most important metric for understanding and predicting the trajectory of viral growth. However, the simplicity of its formula belies a significant degree of nuance. A sophisticated understanding of the K-factor requires moving beyond its basic definition to appreciate its limitations, common misinterpretations, and its true role as a diagnostic tool for the health of a viral system.

The K-Factor Formula () Explained

Before dissecting the formula, it is crucial to provide a point of clarification. The term “K-factor” is a homonym used across various disciplines. The research material for this report contained references to a K-factor in the contexts of sheet metal bending, fire sprinkler discharge rates, and actuarial risk science. The K-factor discussed herein is exclusively the viral coefficient used in growth marketing and has no relation to these other fields.

In the context of product growth, the K-factor (or viral coefficient) is defined as the average number of new users that each existing user successfully brings into the product over a defined time period. It is the numerical output of one full cycle of the viral loop.

The standard formula for calculating the K-factor is:

K-factor = (Invitation Rate) × (Conversion Rate)

where:

- represents the invitation rate: the average number of invitations, referrals, or shares sent by each existing user during the period.

- represents the conversion rate: the average percentage of those invitations that successfully convert the recipient into a new, active user of the product.

For example, if a product has 1,000 active users, and over one month they send a total of 4,000 invitations, the invitation rate is 4000/1000=4. If those 4,000 invitations result in 200 new users signing up, the conversion rate is 200/4000=0.05 (or 5%). The K-factor for that month would be:

K-factor = 4 × 0.05 = 0.2

This means that, on average, every 5 existing users brought in 1 new user during that period.

Interpreting the Viral Coefficient

The numerical value of the K-factor is a powerful predictor of a product’s growth trajectory, indicating whether its user base can grow on its own or if it requires continuous external stimulus from other acquisition channels.

- (Viral Growth): This is the threshold for true virality. When the K-factor is greater than one, each existing user, on average, brings in more than one new user. This creates a compounding effect, leading to exponential or “superlinear” growth. At this stage, the user base expands on its own, and acquisition costs approach zero. Achieving this is the “holy grail” for many startups, as it signifies a self-fueling growth engine.

- (Stable or Linear Growth): When the K-factor is exactly one, each existing user, on average, successfully replaces themselves with one new user. This results in steady, self-sustaining linear growth but does not produce the explosive acceleration characteristic of viral growth.

- (Sublinear Growth or Amplified Decay): When the K-factor is less than one, each user fails to bring in a full new user. In the absence of other acquisition channels, the growth from referrals will eventually slow down and plateau. While this is not exponential growth, it is a critical error to dismiss it as worthless.

Beyond the Formula: Common Misconceptions, Limitations, and the Impact of Churn

An expert-level analysis of the K-factor requires a critical examination of its practical limitations and the common misconceptions that arise from its oversimplified application.

Common Misconceptions:

- “A K-factor less than 1 is worthless.” This is demonstrably false and a dangerous misconception. A positive K-factor, even if small, acts as a powerful and highly cost-effective multiplier on all other acquisition efforts. A K-factor of 0.2, for instance, means that for every 5 customers acquired through paid channels, one additional customer is generated for free. For many SaaS businesses with high lifetime value (LTV), a K-factor as low as 0.16 has been a valuable “side growth accelerator” that enhances the ROI of all other marketing spend.

- “A high K-factor guarantees success.” This is another pervasive myth. A high K-factor is merely a vanity metric if it is not paired with strong user retention. A viral loop that acquires users who quickly churn creates a “leaky bucket” scenario, where growth is unsustainable. For a K-factor to translate into real, long-term growth, it must be greater than the user churn rate. If you acquire 1.2 users for every existing user but 30% of your user base churns in the same period, you are still shrinking.

Limitations of the K-Factor:

- Ignores Other Growth Channels: The basic K-factor model calculates viral growth in a vacuum, assuming no user acquisition from other sources like paid advertising, SEO, or content marketing. In reality, a healthy business has a portfolio of acquisition channels that interact with and influence each other.

- Susceptibility to Distortion: The K-factor can be artificially and temporarily inflated by large-scale paid marketing campaigns.

A sudden influx of new users can create a spike in referral activity that does not reflect the product’s true organic virality, leading to misleading conclusions if not properly cohortized and analyzed.

- Measurement and Attribution Challenges: The simple formula belies the difficulty of accurate measurement. Attributing new users to specific invitations, especially through untrackable word-of-mouth, is challenging.

- Time Lag and Unpredictability: Virality is not always instantaneous. The viral cycle time for some products can be months long (e.g., 8 months for the B2B product EchoSign). This makes the K-factor a lagging indicator that can be unpredictable and difficult to rely on for short-term strategic decisions.

- Not a Proxy for Product-Market Fit: While a high K-factor can be a symptom of a great product, it is not a direct measure of product-market fit, user satisfaction, engagement, or the total addressable market. It measures only one specific dimension: the efficiency of user-driven acquisition.

The true utility of the K-factor is not as a standalone goal, but as a system diagnostic. The formula elegantly splits the viral loop into two distinct, measurable phases. The invitation rate () is a proxy for the existing user’s experience and motivation to share. A low may indicate a lack of user satisfaction, high friction in the sharing process, or a weak incentive. The conversion rate (), on the other hand, is a proxy for the prospective user’s experience. A low suggests a weak value proposition in the invitation, a confusing landing page, or a difficult onboarding process. By measuring and independently, a growth team can diagnose precisely where the viral loop is breaking down and allocate resources to fix the correct problem.

Furthermore, the definition of a “good” K-factor is highly context-dependent and cannot be reduced to the universal benchmark of . Industry benchmarks reveal a wide variance: B2B communication tools like Slack have reported K-factors as high as 8.5, while a more typical B2B SaaS product might have a K-factor of 0.20, and a merchant payment system like Square found a valuable and predictable viral loop with a K-factor of just 0.01. For a high-LTV B2B product, a small K-factor can be enormously profitable. For a low-LTV, ad-supported consumer app, a much higher K-factor is required for the business model to be viable. A “good” K-factor, therefore, is not an absolute number but one that is positive in relation to the product’s unit economics (LTV and CAC).

Section 4: The Art of Persuasion: Designing Effective Invite Incentives

If the viral loop is the engine of growth and the K-factor is its tachometer, then incentives are the fuel. They provide the necessary motivation for users to overcome inertia and actively participate in the sharing process. Designing an effective incentive structure is a strategic exercise in psychology, economics, and product design. It requires a nuanced understanding of what drives users to share and how to align those motivations with the product’s core value and business model.

The Psychology of Sharing: Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation

User sharing behavior is driven by two primary types of motivation:

- Intrinsic Motivation: This is the desire to perform an action for its own sake, driven by internal rewards such as satisfaction, purpose, or social recognition. In the context of virality, intrinsic motivation fuels “organic viral loops”. Users share because:

- They have a genuine enthusiasm for the product and want to help others by recommending it.

- Sharing enhances their social status or makes them look good to their peers. This is known as gaining “social currency”.

- The act of sharing is necessary to unlock the product’s full value, as is the case with collaborative tools.

- Extrinsic Motivation: This is the desire to perform an action in order to obtain an external reward or avoid punishment. In virality, this fuels “incentivized viral loops”. Users share because they are offered a tangible reward, such as a discount, cash, or a product upgrade. These incentives leverage powerful psychological principles like the human desire for reward and the principle of reciprocity, where individuals feel compelled to return a favor.

The most potent viral engines do not rely on one type of motivation alone. They are built upon a foundation of a great product that users are intrinsically motivated to share, which is then amplified by a well-designed extrinsic incentive that provides a compelling reason to act now.

Monetary vs. Non-Monetary Rewards: A Cost-Benefit Analysis

Incentives can be broadly categorized as either monetary or non-monetary, each with distinct advantages and disadvantages.

- Monetary Rewards: These are financial incentives such as cash payments, account credits, gift cards, or discounts on future purchases.

- Pros: They are tangible, universally understood, and highly effective for driving short-term action and attracting new users. For transactional products like PayPal, offering cash was a powerful way to both demonstrate the product’s utility and rapidly acquire a user base.

- Cons: Monetary rewards can feel transactional, potentially weakening a user’s intrinsic motivation to share. They can create a sense of entitlement and are a strong magnet for fraudulent activity, as abusers are drawn to the direct financial gain. Furthermore, their motivational impact can be short-lived, fading once the reward is received.

- Non-Monetary Rewards: These are incentives that provide value without a direct cash equivalent, such as product upgrades, access to exclusive features, branded merchandise (swag), or free content.

- Pros: These rewards can be significantly more cost-effective and can have a higher perceived value than their actual cost to the company. They foster longer-term engagement by deepening a user’s investment in the product ecosystem. They also possess “trophy value,” serving as a lasting reminder of the achievement and making them easier for users to discuss socially. The classic example is Dropbox’s offer of additional storage space, which was not only low-cost to provide but also made the product stickier for the user.

- Cons: The perceived value of non-monetary rewards can vary greatly between individuals. An exclusive feature may be highly motivating to a power user but irrelevant to a casual one. They may also be less effective if users have more immediate financial needs.

The most successful incentive programs are not generic but are deeply aligned with the product’s core value. PayPal offered money. Dropbox offered storage. The reward should reinforce the reason users are using the product in the first place, thereby increasing their long-term engagement and LTV.

One-Sided vs. Two-Sided Incentives: Balancing Generosity and Motivation

Another critical design choice is who receives the reward.

- One-Sided Incentives: This model rewards only one party in the transaction: either the existing user (the referrer) or the new user (the friend).

- Rewarding the Referrer Only: This directly motivates the existing user to share but can feel self-serving, potentially reducing their willingness to invite close friends. It is often used by newer companies to quickly generate brand awareness.

- Rewarding the Friend Only: This acts as a strong acquisition offer for the new user but provides no extrinsic motivation for the existing user to make the effort to share.

- Two-Sided (or Double-Sided) Incentives: This model rewards both the referrer and the referred friend, creating a win-win scenario. This is widely considered the best option for most businesses.

- Psychological Advantage: Two-sided incentives are powerful because they reframe the social dynamic. The referrer is no longer just profiting from their friend; they are giving their friend a gift or a special offer. This leverages the principle of reciprocity and enhances the referrer’s social currency, making them more comfortable and enthusiastic about sharing.

- Symmetrical vs.

Asymmetrical Rewards: The rewards for both parties can be identical (e.g., “Give $10, Get $10”) or different (e.g., “Give your friend 20% off, Get a $20 credit”). Asymmetrical rewards can be used strategically to provide a more compelling offer to the new user to maximize conversion, while still rewarding the referrer.

Advanced Incentive Structures

Beyond the basic models, sophisticated viral engines often employ more complex structures to drive sustained engagement and maximize referrals.

- Tiered or Milestone Rewards: Instead of a flat reward for each referral, the value of the reward increases as the user reaches specific milestones (e.g., refer 1 friend, get 100 gems; refer 5 friends, get 1000 gems and an exclusive item). This gamifies the process, tapping into the human desire for achievement and progression.

- Gamification and Leaderboards: This involves adding game-like elements to the referral program, such as achievement badges, points systems, or public leaderboards that rank the top referrers for a given period. The element of competition can be a powerful motivator, as demonstrated by a pre-launch campaign for Jet.com where one participant reportedly spent $18,000 on ads to win the top spot on the referral leaderboard.

- Contests and Giveaways: This structure offers participants a chance to win one or more large prizes, with each successful referral counting as an entry into the drawing. This can attract a large volume of shares, though the quality of the resulting leads may be lower.

- Time-Limited Offers: Creating a sense of urgency by offering enhanced rewards for a limited time (e.g., “Refer a friend this week and get double rewards!”) can significantly boost short-term participation and create spikes in acquisition.

| Incentive Structure | Description | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-Sided (Referrer) | Only the existing user receives a reward for a successful referral. | Simple, directly motivates sharing, cost-effective. | Can feel self-serving to the referrer, provides no incentive for the friend to convert. | Early-stage companies needing brand awareness; products with a very strong intrinsic value. |

| Two-Sided Symmetrical | Both the referrer and the friend receive the same reward (e.g., “Give $10, Get $10”). | Creates a fair win-win, leverages reciprocity, easy to communicate. | Can be more expensive than one-sided models. | Most consumer products, e-commerce, and subscription services where a balanced offer is key. |

| Two-Sided Asymmetrical | The referrer and friend receive different rewards (e.g., “Give 20% off, Get $20”). | Allows for strategic optimization (e.g., a larger discount for the new user to drive conversion). | Can be more complex to communicate and balance. | High-value products or services where the value of a new customer justifies a larger acquisition incentive. |

| Monetary (Cash/Credit) | Rewards are in the form of direct financial value. | Universally appealing, strong short-term motivator. | Attracts fraud, can feel transactional, may devalue the brand. | Financial services (e.g., PayPal), marketplaces, and kickstarting growth in new networks. |

| Non-Monetary (Product) | Rewards are in the form of product features, usage, or upgrades (e.g., more storage). | Cost-effective, increases user investment in the product, builds long-term loyalty. | Perceived value can vary widely among users. | SaaS products, mobile games, and platforms where increased usage is a key business goal. |

| Tiered/Milestone | Reward value increases as the user refers more people. | Encourages repeat referrals, gamifies the experience, identifies super-advocates. | Can be complex to set up and track. | Mature products with an engaged user base looking to maximize output from top referrers. |

Section 5: Virality in Practice: Comparative Analysis of Industry Leaders

Theoretical frameworks and strategic models are best understood through their real-world application. By dissecting the viral engines of iconic companies, it is possible to see how these principles are translated into tangible product features and growth outcomes. This section examines the landmark cases of Dropbox, PayPal, and Airbnb, followed by a comparative analysis of how virality mechanics are adapted across different industries.

Case Study 1: Dropbox – The Product-Centric Viral Loop

- The Result: The company grew its user base by an astounding 3900%, from 100,000 to 4 million registered users, in just 15 months between 2008 and 2010. At its peak, the referral program was responsible for 35% of all daily signups. In April 2010 alone, users sent 2.8 million referral invitations.

- The Incentive: Dropbox employed a two-sided, non-monetary incentive that was perfectly aligned with its core product value. Both the referrer and the newly signed-up friend received 500MB of free bonus storage space. This strategy was brilliant for two reasons: first, the marginal cost of providing additional storage was near zero, making the program highly scalable and profitable. Second, the reward itself—more storage—increased the user’s dependency on and investment in the Dropbox ecosystem, making them less likely to churn and more likely to need even more storage in the future.

- The Viral Loop: The program’s success was rooted in its seamless integration into the user experience.

- Onboarding Integration: The referral offer was a key step in the user onboarding process, ensuring that nearly 100% of new users were aware of the program at the moment they were most engaged and excited about the product.

- Frictionless Sharing: The referral process was consolidated onto a single, simple page where users could invite contacts from their email address book or share a unique referral link with just a few clicks.

- Clear Motivation and Tracking: The program clearly displayed the benefits and provided users with a dashboard to track the status of their invitations and the total amount of bonus space they had earned, creating a compelling feedback loop that encouraged continued sharing.

Case Study 2: PayPal – Kickstarting a Network with Aggressive Monetary Incentives

PayPal’s early growth strategy demonstrates how a high-cost, aggressive viral campaign can be used as a short-term investment to solve the “cold start” problem and ignite a powerful network effect.

- The Result: The referral program was the catalyst for achieving a staggering 7% to 10% daily growth rate, catapulting the user base from 1 million to over 5 million in just a few months during the year 2000, and eventually to over 100 million users.

- The Incentive: PayPal deployed a direct and potent two-sided monetary incentive. Initially, the company literally paid users for growth, offering $20 to a new user for signing up and $20 to the referrer. This was real cash that could be withdrawn or used, representing a significant customer acquisition cost. As the network grew, the incentive was strategically reduced to $10, then $5, and was eventually phased out entirely once the network effect became strong enough to provide its own intrinsic incentive for joining. The total expenditure on this program was estimated by Elon Musk to be around $60 to $70 million.

- Strategic Context: This seemingly unsustainable strategy was a calculated move. PayPal was operating in a nascent, “winner-takes-all” market for online payments where having a large network of users was the primary determinant of value. Traditional advertising was proving too expensive and ineffective. The company’s leadership correctly identified that they needed to buy liquidity and reach critical mass faster than any competitor. The high cash incentive was the price they paid to rapidly build their two-sided network, a strategy that proved immensely successful and established their market dominance.

Case Study 3: Airbnb – Leveraging Trust, Altruism, and Two-Sided Value

Airbnb’s referral program showcases a more psychologically nuanced approach, designed not just to drive signups but to overcome the significant trust barrier inherent in its business model—staying in a stranger’s home.

- The Result: The company’s second-generation referral program, “Referrals 2.0,” was a massive success, driving a 300% increase in both bookings and signups compared to its initial, less-promoted version.

- The Incentive: Airbnb used a two-sided incentive model based on travel credits. Both the referrer and the referred friend received a $25 credit toward a booking. Critically, the program also featured a differentiated, higher-value incentive for host acquisition: a referrer would earn a more substantial $75 credit when their friend listed a property and completed their first booking. This asymmetrical structure smartly recognized that new inventory (hosts) was more valuable to the platform’s health than new demand (guests).

- The Psychology of the Loop:

- Building Trust with Social Proof: The invitation process was personalized to build immediate trust. The landing page shown to a new user prominently featured the name and profile picture of the friend who referred them, instantly transforming an anonymous corporate invitation into a trusted personal recommendation.

- Harnessing Altruism: Through extensive A/B testing, Airbnb’s growth team discovered a key psychological insight: messaging that framed the referral as an act of generosity (“Give your friends $25 to travel”) performed significantly better than messaging that focused on the referrer’s personal gain (“Get $25 when your friends travel”). This altruistic framing removed social friction and became the cornerstone of the program’s messaging.

These case studies reveal that there is no single “best” viral strategy.

The design of the viral engine—particularly its incentive structure—must be deeply and uniquely tailored to the product’s core value proposition, the primary barrier to its adoption, and the underlying economics of its business model.

Comparative Analysis: Virality Mechanics Across Industries

The principles of virality are universal, but their implementation varies significantly across different product categories. Understanding these patterns is crucial for setting realistic benchmarks and designing appropriate strategies.

| Industry | Primary Viral Mechanism | Common Incentive Types | Typical K-Factor Profile | Key Success Factors | Representative Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2B SaaS (Collaboration) | Pull Virality / Inherent: Value requires inviting colleagues to collaborate within the product. | Non-monetary: Feature unlocks, increased usage limits, extended trials. | Low to moderate (e.g., 0.2-0.7). Highly valuable due to high LTV. | Seamless team onboarding, frictionless invitation flow within core workflows. | Slack, Figma, Zoom |

| Social Networks | Network Virality / Infectious: Value is the network itself; users must invite friends to connect. | Implicit: The ability to connect with one’s social graph is the primary incentive. | Can be very high (>1) during the initial growth phase, then plateaus. | Reaching critical mass quickly, leveraging existing contact lists. | LinkedIn, Facebook |

| Mobile Games | Outbreak / Social Virality: Driven by competition, achievement, novelty, and social sharing of results. | In-game currency, exclusive items, power-ups, tiered rewards. | Can be high initially but often decays quickly; must outpace high churn. | Instant gratification, strong social hooks (leaderboards, challenges), gamified rewards. | Among Us, Candy Crush |

| E-commerce / DTC | Incentivized WOM: Sharing is not core to the product use but is encouraged via a referral program. | Two-sided monetary: Discounts, store credit for both referrer and friend. | Low (e.g., <0.5), but can significantly reduce CAC and increase LTV. | Compelling two-sided offer, easy sharing post-purchase, clear value proposition. | Harry’s, Rothy’s |

| Content Platforms (UGC) | Distribution / Exposure Virality: Users share content they create or discover, implicitly promoting the platform. | Implicit: Social currency, fame, or self-expression gained from sharing content. | Varies widely based on content quality and shareability. | Tools that create high-quality, shareable “viral carriers” (e.g., videos, designs). | TikTok, Canva, YouTube |

Section 6: Navigating the Pitfalls: Risks, Challenges, and Mitigation Strategies

While the pursuit of virality offers the promise of exponential growth, it is a high-stakes endeavor fraught with significant risks. A viral event, whether positive or negative, represents a loss of control for the brand. An expert approach to engineering virality must include a sober assessment of these potential pitfalls and the implementation of robust strategies to mitigate them. The primary challenges fall into three categories: loss of message control, operational strain from rapid scaling, and the financial and reputational damage from incentive abuse.

The Double-Edged Sword: Negative Virality and Loss of Control

The very mechanism that makes virality powerful—the rapid, decentralized spread of a message through user networks—is also its greatest risk.

- Loss of Control: Once content is released into the wild and begins to spread organically, the originating brand loses control over its context, interpretation, and modification. A message can be stripped of its original intent, parodied, or used in ways that were never anticipated, potentially diluting or damaging the brand’s image.

- Negative Virality: Not all virality is good virality. A campaign that is perceived as tone-deaf, offensive, or inauthentic can trigger a wave of public backlash. Negative sentiment often spreads faster and with greater emotional intensity than positive sentiment, and the resulting reputational harm can be swift and severe.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Craft Clear and Simple Messaging: A core message that is concise, unambiguous, and simple is less susceptible to misinterpretation as it propagates through networks.

- Active Monitoring and Engagement: Brands must use social listening and monitoring tools to track the conversation around their campaign in real-time. This allows for rapid engagement to correct misunderstandings, address criticism, and guide the narrative where possible.

- Prioritize Authenticity and Sensitivity: The risk of backlash is highest when a brand’s message feels inauthentic or insensitive to cultural or current events. Thorough audience research and a genuine alignment with brand values are the best defenses against this type of negative virality. The risk of message distortion is also inherently lower when the viral mechanism is built directly into the product’s core function (e.g., sharing a collaborative document) rather than existing as a separate, context-free marketing campaign (e.g., a humorous video).

Operational Strain: The Perils of Success

Ironically, one of the greatest risks of a successful viral campaign is success itself. A sudden, exponential spike in demand can place an unbearable strain on a company’s operational infrastructure.

- Scalability Problems: A viral hit can lead to a massive influx of website traffic, product signups, or customer orders that can overwhelm servers, deplete inventory, and overload customer support systems.

- Reputational Damage: If the company is unprepared, this operational failure can turn a marketing triumph into a brand disaster. Server crashes, shipping delays, unanswered support tickets, and a general decline in service quality can lead to widespread customer dissatisfaction, permanently damaging the brand’s reputation at the very moment of its greatest visibility.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Prepare for Scale: Before launching a campaign with viral potential, a company must stress-test its technical infrastructure and operational workflows. Systems should be designed to handle a significant increase in load.

- Transparent Communication: In the event of operational issues, proactive and transparent communication with customers is critical. Informing users about potential delays and managing their expectations can mitigate frustration and preserve trust.

Combating Incentive Abuse: Identifying and Preventing Referral Fraud

Referral programs, especially those with monetary incentives, are a natural and frequent target for fraudulent actors seeking to exploit the system for personal gain. This abuse inflates acquisition metrics, drains marketing budgets, and can damage the integrity of the program for legitimate users.

Common Types of Referral Fraud:

- Self-Referral: The most common form of abuse, where a single user creates multiple fake or duplicate accounts using different email addresses to refer themselves and collect rewards.

- Account Cycling: An extension of self-referral where fraudsters create, use, and then delete fake accounts in a continuous cycle to repeatedly exploit new-user bonuses.

- Return Abuse: A coordinated effort where a referred “friend” makes a qualifying purchase to trigger the reward for the referrer, and then returns the product for a full refund after the reward has been paid out.

- Discount Broadcasting: When a user posts their unique referral link or code on public coupon websites, forums, or social media, harvesting rewards from strangers rather than through genuine personal recommendations.

Prevention and Detection Strategies:

- Incentive Design: The first line of defense is a well-designed incentive structure. Offering non-monetary rewards (e.g., product features, in-game currency) is less attractive to fraudsters than direct cash payments. Furthermore, rewards should be tied to meaningful user actions that demonstrate real engagement—such as a completed purchase above a minimum value threshold—rather than just a simple signup.

- Technical Measures: Implement robust fraud detection systems. This includes tracking IP addresses and device fingerprints to identify and block users creating multiple accounts from the same source. Velocity checks can flag suspicious patterns, such as an unusually high number of referrals from a single user in a short time.

- Program Rules and Enforcement:

- Clear Terms and Conditions: Explicitly state in the program’s terms of service that fraudulent activities, including self-referral and posting on coupon sites, are prohibited and will result in disqualification.

- Implement a Review Period: Do not pay out rewards instantly. Institute a mandatory review or “pending” period before rewards are granted. This delay provides time to detect fraudulent activity and should ideally be aligned with the product’s return policy to mitigate return abuse.

Section 7: Conclusion: A Framework for Building a Sustainable Viral Engine

Virality is not an unpredictable force of nature but an outcome that can be systematically engineered. It is the result of a cohesive strategy that integrates product design, user psychology, and data-driven optimization. For businesses seeking to harness this powerful growth mechanism, the path forward is not to chase fleeting trends but to build a durable, self-sustaining viral engine. This concluding section synthesizes the report’s findings into an actionable framework and offers final recommendations for achieving long-term, defensible growth.

Synthesizing Best Practices into an Actionable Strategic Framework

A successful viral engine is built upon a clear and logical foundation. The following framework consolidates the best practices identified throughout this analysis into a strategic checklist for product leaders and growth teams.

Establish the Foundation (Product-Value Fit)

Before any viral mechanics are built, the product itself must be referable. It must deliver a remarkable, high-value experience that solves a real problem for its users. Virality amplifies what is already there; it cannot create value out of a mediocre product. The first step is always to build something that users are intrinsically motivated to share.

Design the Mechanism (The 4-Step Framework)

Based on the model for viral design, every aspect of the sharing process must be deliberately engineered.

- Step 1: Identify the “Why.” Determine the core motivation for a user to share. Is it for a professional benefit, to enhance their social status, out of practical necessity to use the product, or for a financial reward?

- Step 2: Define the “What.” Specify the “viral carrier”—the unit of value that will travel from the user to their network. This could be a direct invitation, a piece of user-generated content, a report of results, or an embeddable widget.

- Step 3: Determine the “Where.” Integrate sharing capabilities into the channels and platforms where the user’s target network already exists, such as email, social media, or messaging apps.

- Step 4: Craft the “Why” for the Recipient. The invitation or shared content must present a clear, compelling, and frictionless value proposition for the new user, answering the question “What’s in it for me?”

Align the Incentive

The reward structure must be a strategic extension of the business model, not an afterthought. The incentive should reinforce the product’s core value (e.g., offering storage for a storage product) and be economically sustainable in relation to customer lifetime value (LTV). Two-sided incentives that empower the referrer to give a gift are psychologically potent and generally outperform one-sided models.

Measure and Optimize the System

A viral engine requires continuous monitoring and iteration. Teams must obsessively track the key performance indicators of the system: the K-factor (broken down into its components, and ), the Viral Cycle Time, and the churn rate of virally acquired users. This data provides the necessary feedback to identify bottlenecks and systematically optimize each stage of the viral loop.

The Symbiotic Relationship Between Product Value and Viral Amplification

The central thesis of this report is that sustainable virality exists at the intersection of product value and network amplification. These two forces are symbiotic and mutually reinforcing. A viral loop without a valuable product at its core creates a “leaky bucket,” acquiring users who quickly churn because the product fails to deliver on its promise.

Conversely, a valuable product without well-designed viral mechanics will grow slowly, relying on less efficient and more expensive acquisition channels.

True exponential growth is achieved only when a high-value product experience is seamlessly connected to a low-friction viral engine. The exceptional product experience creates the intrinsic motivation to share, and the well-designed viral loop provides the extrinsic push and the mechanical means to do so. In this ideal state, the viral loop brings new users to the door, and the core product value convinces them to stay, engage, and ultimately become the next wave of advocates, perpetuating the cycle.

Final Recommendations for Long-Term, Defensible Growth

For organizations aiming to build an enduring business, virality should be viewed as a powerful tool, but not the ultimate goal. The following recommendations provide a strategic hierarchy for deploying this tool effectively.

- Prioritize Retention Above All Else: Before dedicating significant resources to optimizing viral loops or K-factor, a business must first solve for retention. A “sticky” product with low churn is the non-negotiable prerequisite for any sustainable growth strategy. Pouring users into a leaky bucket is a recipe for failure.

- Build Virality In, Don’t Bolt It On: The most effective and defensible viral mechanics are those that are integral to the core product experience. Virality should be a consideration in the initial product design phase, not a marketing program that is bolted on after launch.

- Measure Holistically: Do not become fixated on a single, top-line K-factor. A sophisticated growth strategy requires a dashboard of metrics. Track the invitation rate (), the conversion rate (), the Viral Cycle Time, and, most importantly, the cohort retention and LTV of virally acquired users to understand the true health and profitability of the viral engine.

- Choose Defensibility Over Speed: While virality provides speed, network effects provide defensibility. If a business model allows for the development of a network effect, that should be the ultimate strategic priority. Virality is the accelerator that helps a company reach the critical mass needed for a network effect to lock in, creating a long-term, sustainable competitive moat that a simple viral mechanism alone cannot provide.