Jekyll Plugins & GitHub Pages: Architecture & Deployment

Section 1: The Jekyll Plugin Architecture: A Deep Dive into Core Extension Mechanisms

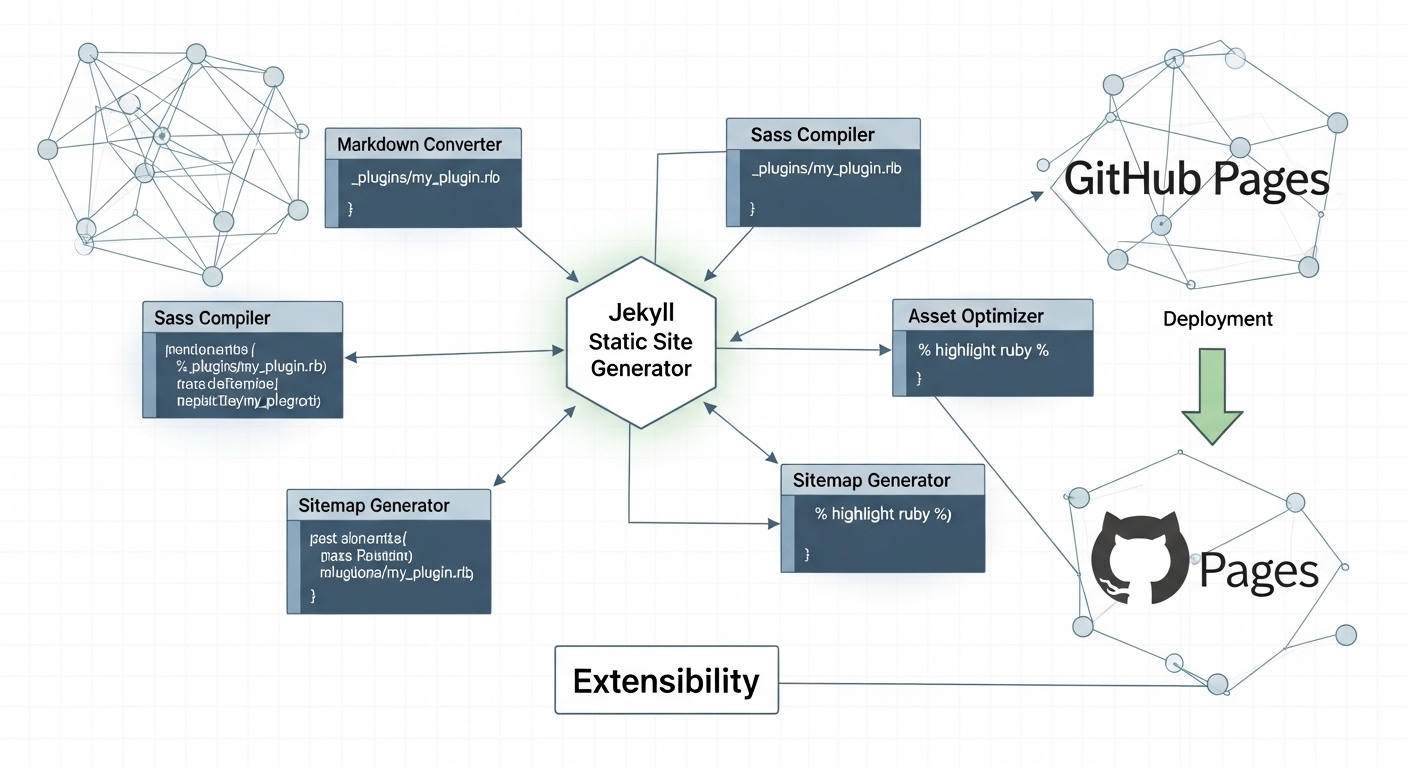

Jekyll, a static site generator, offers a robust plugin system that serves as a core architectural feature, enabling developers to extend and customize its behavior without modifying the underlying source code. This approach is fundamental to the platform’s philosophy, promoting maintainability, modularity, and the separation of site-specific logic from the generator’s core engine. By leveraging a system of hooks and well-defined extension points, developers can inject custom Ruby code at various stages of the site generation process, thereby tailoring the final output to meet highly specific requirements.

1.1 The Philosophy of Extensibility: Modifying Behavior Without Altering Core Code

The design of Jekyll’s plugin system is centered on a hook-based architecture. This model allows custom code to be executed at specific, predefined moments within the build lifecycle. Instead of requiring developers to fork and alter the Jekyll source for custom functionality—a practice that would create significant maintenance overhead and complicate future upgrades—the plugin system provides a stable and documented Application Programming Interface (API). This API allows for the creation of new content, the transformation of existing content, and the modification of the build process itself.

The primary benefit of this architecture is the ability to run arbitrary Ruby code within the context of the Jekyll build. This empowers developers to automate complex tasks, integrate with external data sources, and implement features not available in the core generator. For example, a plugin can be designed to fetch data from an API and generate a new page for each data point, or to implement a custom markup language converter. This extensibility transforms Jekyll from a simple content processor into a versatile framework for static site generation.

1.2 Plugin Loading and Installation Protocols

Jekyll supports two primary methods for installing and loading plugins, each with distinct advantages and use cases. The evolution from a simple directory-based approach to a sophisticated gem-based dependency management system reflects the maturation of the Jekyll ecosystem and its alignment with standard practices in the broader Ruby community.

The _plugins Directory

The most direct method for loading a plugin is to place its source file—a Ruby file with a .rb extension—into a _plugins directory at the root of the Jekyll site. During the build process, Jekyll automatically loads and executes any Ruby files found in this directory. This approach is straightforward and well-suited for developing site-specific, custom-coded plugins that are not intended for wider distribution. However, its simplicity comes with a significant limitation: it is the primary mechanism disabled by security-conscious environments like GitHub Pages, which run Jekyll in a “safe mode” that prevents the execution of arbitrary code from this directory.

Gem-based Management

The modern and recommended approach for managing plugins is through RubyGems, the standard package manager for the Ruby language. This method treats plugins as versioned, distributable packages and leverages Bundler, a dependency management tool, to ensure a consistent and reproducible build environment. Implementation involves two key configuration files:

- _config.yml: This is Jekyll’s main configuration file. To activate a gem-based plugin, its name must be listed under the plugins array (or the gems key for Jekyll versions prior to 3.5.0). This explicitly instructs Jekyll to require and load the specified gem during initialization.

- Gemfile: This file is used by Bundler to manage all of the project’s gem dependencies, including Jekyll itself and any plugins. By listing plugins in the Gemfile, a developer can lock in specific versions, preventing unexpected breakages when a dependency is updated. Running the bundle install command reads this file and installs all the necessary gems.

This gem-based workflow is considered a best practice because it makes a Jekyll project self-contained and portable. A new developer can clone the repository, run a single command, and have the exact same environment, which is crucial for collaborative projects and reliable deployments.

The :jekyll_plugins Group

Within the Gemfile, Bundler allows for the organization of gems into groups. Jekyll recognizes a special group named :jekyll_plugins. Any gem placed within this group is automatically required and loaded by Jekyll at the very beginning of its execution, bypassing the need for it to be listed in the _config.yml file. This early-loading mechanism is powerful and serves a specific purpose. It is designed for plugins that need to modify Jekyll’s core behavior or extend its command-line interface before the standard site build process begins. For instance, a plugin like jekyll-compose, which adds new commands such as jekyll post “My New Post”, must be loaded when the jekyll executable is invoked, not when the build is already underway. The standard loading mechanism via _config.yml occurs too late for such functionality, making the :jekyll_plugins group an essential hook for these runtime-enhancement plugins.

1.3 The Jekyll Build Lifecycle and Plugin Intervention Points

To fully appreciate how plugins function, it is essential to understand the sequential stages of a jekyll build. While the process is complex, it can be simplified into several key phases. Each phase presents an opportunity for a specific type of plugin to intervene and modify the outcome.

- Configuration and Initialization: Jekyll reads the _config.yml file and command-line flags to establish the build environment. Gem-based plugins are loaded during this phase.

- Site Inventory (Reading): Jekyll traverses the source directory, reading all files and parsing YAML front matter to create in-memory objects for pages, posts, and collection documents.

- Generation: This is the first major extension point. Generator plugins run after the initial inventory is complete. They can programmatically create new page and post objects that are added to the site’s collection of content to be processed in subsequent stages.

- Conversion: Each document is passed through the appropriate converter based on its file extension. For example, a .md file is processed by a Markdown converter to produce HTML. This is where Converter plugins execute.

- Rendering: The converted content of each document is then rendered within its specified layout(s) using the Liquid templating engine. During this phase, Tag and Filter plugins are executed to process Liquid markup and manipulate data.

- Writing: The final, fully rendered HTML for each page is written to the destination directory (typically _site).

Hooks provide an even more granular level of control, allowing plugins to execute code at very specific moments, such as before or after a page is rendered (:pages, :pre_render or :pages, :post_render). This structured, phased approach is what makes the plugin system so robust, as it ensures that different types of extensions operate in a predictable order, preventing conflicts and enabling complex interactions between them.

Section 2: A Taxonomy of Jekyll Plugins: Types and Use Cases

The Jekyll plugin system is organized into a clear taxonomy of types, each designed to hook into a specific part of the build lifecycle. This classification is not merely academic; it is a direct reflection of Jekyll’s internal architecture, with each plugin type corresponding to a distinct, extensible module within the Jekyll codebase. Understanding this taxonomy provides developers with a mental model for selecting the right tool for a given task or for designing their own custom plugins.

2.1 Generators

Generators are plugins that programmatically create new content during the build process. They execute after Jekyll has inventoried all existing static files, pages, and posts but before any content is rendered to the final site. A generator’s primary function is to create new Jekyll::Page, Jekyll::Post, or Jekyll::Document objects in memory, which are then treated by Jekyll as if they were physical files in the source directory. This capability is invaluable for automating the creation of content that follows a predictable pattern or is based on data.

- Use Cases: Common applications for generators include creating an Atom/RSS feed from the site’s posts (jekyll-feed), generating a sitemap.xml file for search engine crawlers (jekyll-sitemap), and building archive pages for each category or tag used on the site (jekyll-archives).

2.2 Converters

Converters are responsible for transforming content from one markup language into another, most commonly from a format like Markdown or Textile into HTML. A converter plugin registers itself with Jekyll, declaring which file extensions it can process (e.g., .md, .textile) and what the file extension of its output will be (e.g., .html). Jekyll’s core includes a Markdown converter, but plugins can be used to add support for other languages or to replace the default converter with an alternative one that has different features.

- Use Cases: Examples include adding support for the Textile markup language (jekyll-textile-converter), converting CoffeeScript files to JavaScript (jekyll-coffeescript), or even transpiling Ruby code to JavaScript using Opal (jekyll-opal).

2.3 Tags

Tag plugins create custom Liquid tags, which allow for the embedding of complex or dynamically generated content directly within Markdown or HTML files. Liquid tags are denoted by the {%…

“`

%} syntax. When Jekyll’s Liquid renderer encounters a custom tag during the rendering phase, it executes the corresponding plugin’s code. This allows developers to abstract complex logic into a simple, reusable tag.

- Use Cases: Built-in examples include the {% include %} and {% highlight %} tags. Custom tag plugins are often used for embedding external content, such as a YouTube video (jekyll-youtube), or for generating dynamic output, such as a relative URL path to a site asset (jekyll-asset-path-plugin).

2.4 Filters

Filter plugins create custom Liquid filters, which are used to manipulate text, numbers, or other data within a template. Filters are applied using the pipe | character within a Liquid output tag, which uses the {{… }} syntax. A filter is essentially a method that takes an input, processes it, and returns the modified output.

- Use Cases: Filter plugins are ideal for formatting data for display. Examples include a filter that converts a date into a human-readable “time ago” format (jekyll-time-ago), a filter that generates a table of contents from a page’s headings (jekyll-toc), or a filter that obfuscates email addresses to protect them from spam bots (jekyll-email-protect).

2.5 Commands

Command plugins extend the jekyll command-line executable with new subcommands. This allows developers to automate common workflow tasks and integrate custom scripts directly into the Jekyll CLI. These plugins must be loaded using the :jekyll_plugins group in the Gemfile to ensure they are available when the jekyll command is run.

- Use Cases: The most prominent example is jekyll-compose, which adds subcommands like

jekyll post,jekyll page, andjekyll draftto streamline the creation of new content files with the correct naming convention and front matter boilerplate.

2.6 Hooks

Hooks are the most powerful and low-level plugin type, providing fine-grained control over the build process by allowing custom code to be triggered at specific lifecycle events. Unlike the other plugin types, which are tied to a specific function (like generating a page or converting a file), hooks can be registered to run at dozens of different points, such as before or after the site is processed, or before or after an individual document is rendered. This versatility means hooks can often be used to achieve the functionality of other plugin types, albeit with potentially more complex code. They represent the ultimate escape hatch for developers needing to implement highly customized build logic.

- Use Cases: Hook-based plugins are often used for site-wide modifications that need to happen at a precise moment. Examples include jemoji, which uses a hook to render GitHub-flavored emoji in rendered HTML, and jekyll-mentions, which converts @username mentions into links to GitHub profiles.

The following table provides a comparative summary of the different plugin types, clarifying their roles and intervention points within the Jekyll build process.

| Plugin Type | Primary Function | Execution Stage in Build Lifecycle | Example Syntax/Invocation | Canonical Example Plugin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generator | Programmatically create new pages, posts, or documents. | After site inventory, before rendering. | N/A (Automatic) | jekyll-sitemap |

| Converter | Transform content from one markup format to another. | During the conversion phase. | N/A (Based on file extension) | jekyll-textile-converter |

| Tag | Embed complex or dynamic content within layouts/pages. | During the Liquid rendering phase. | {% my_custom_tag %} |

jekyll-youtube |

| Filter | Manipulate data or text output within templates. | During the Liquid rendering phase. | {{ variable | my_custom_filter }} |

jekyll-time-ago |

| Command | Extend the jekyll executable with new subcommands. | At the command-line interface level. | jekyll my_command |

jekyll-compose |

| Hook | Execute custom code at specific build lifecycle events. | Various (e.g., :site, :post_render). |

N/A (Automatic, event-triggered) | jemoji |

Section 3: Core Functionality Enhancement: In-Depth Analysis of Essential Plugins

While the Jekyll plugin ecosystem is vast, a small suite of plugins has emerged as essential for transforming a basic Jekyll site into a fully-featured, modern publishing platform. These plugins address fundamental requirements for search engine optimization (SEO), content syndication, and user navigation. Their inclusion as dependencies in both the default minima theme and the official github-pages gem underscores their status as a “core suite” of functionality. Without them, developers would face the complex and error-prone task of manually implementing these critical features.

3.1 jekyll-seo-tag: Mastering On-Page SEO and Structured Data

The jekyll-seo-tag plugin is a comprehensive solution for managing on-page SEO. Its primary purpose is to automatically generate a complete set of metadata tags in the <head> of a site’s HTML, which are crucial for how search engines and social networks index and display content.

- Purpose: The plugin outputs title tags, meta descriptions, canonical URLs, Open Graph tags for social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter Card metadata, and JSON-LD structured data for rich search results. This automates adherence to SEO best practices, a task that would otherwise require meticulous manual effort.

- Installation and Usage: Installation follows the standard gem-based method: add

gem 'jekyll-seo-tag'to the Gemfile and add- jekyll-seo-tagto thepluginsarray in_config.yml. The plugin is then activated by placing a single Liquid tag,{% seo %}, just before the closing</head>tag in the site’s default layout file. - Configuration: The plugin is highly configurable through both global settings and page-specific overrides. In

_config.yml, a developer can define site-wide values fortitle,description,url,logo, and social media handles fortwitterandfacebook. These global defaults can be overridden on any page or post by setting corresponding variables (e.g.,title,description,image,author) in the YAML front matter. - Advanced Features: For more granular control, the plugin offers advanced customization. Developers can specify the type of content for JSON-LD structured data (e.g.,

BlogPosting,NewsArticle), which helps search engines better understand the page’s content. It is also possible to set a customcanonical_urlin the front matter, a critical feature for managing syndicated content or avoiding duplicate content penalties. The plugin also allows for defining a default fallback image for social sharing and customizing the image output with specific dimensions and alt text.

3.2 jekyll-sitemap: Ensuring Search Engine Discoverability

The jekyll-sitemap plugin provides a simple yet vital function: it automatically generates a sitemaps.org-compliant XML sitemap for the entire site. This file acts as a roadmap for search engine crawlers, helping them discover and index all of the site’s pages and posts efficiently.

- Purpose: By providing a comprehensive list of all site URLs, a sitemap ensures that search engines are aware of all available content, including pages that might not be easily discoverable through internal links alone. This is a foundational element of technical SEO.

- Installation and Usage: This plugin is a prime example of a “set it and forget it” tool. It is installed as a gem and added to the

pluginslist in_config.yml. As a generator plugin, it requires no template tags; it runs silently in the background during every build, creating or updating thesitemap.xmlfile in the root of the output directory. - Configuration: The single most critical configuration setting for this plugin is the

urlvariable in_config.yml. This must be set to the site’s full base URL (e.g.,https://example.com) to ensure that the links in the sitemap are absolute, as required by the sitemap protocol. - Customization: While the plugin is designed to be automatic, it offers control over which pages are included. A developer can exclude any page or post from the sitemap by adding

sitemap: falseto its front matter. It is also possible to exclude entire directories or files based on a glob pattern using thedefaultsconfiguration in_config.yml. The plugin also intelligently determines the<lastmod>date for each URL, prioritizing alast_modified_atfront matter variable, then falling back to the file’s modification timestamp (if the jekyll-last-modified-at plugin is used), and finally to the post’s date.

3.3 jekyll-feed: Generating Atom/RSS Feeds for Content Syndication

The jekyll-feed plugin automates the creation of an Atom (a modern alternative to RSS) feed for a site’s posts. This allows users to subscribe to the site’s content using a feed reader, providing a direct channel for content distribution and audience engagement.

- Purpose: Content syndication via feeds is a long-standing web standard that remains a powerful tool for building a loyal readership. The jekyll-feed plugin makes implementing this feature trivial.

- Installation and Usage: Following the standard installation process, the plugin automatically generates a feed at

/feed.xml. To help browsers and feed readers discover this feed, the plugin provides an optional helper tag,{% feed_meta %}, which should be placed in the<head>of the site’s layout. This tag renders the necessary<link>elements for autodiscovery. - Configuration: The plugin intelligently reuses existing site-wide variables from

_config.yml, such astitle,description, andauthor, to populate the feed’s metadata.

“`html

The output path of the feed can be customized (e.g., to /blog/feed.atom), and the number of posts included in the feed can be adjusted from the default of 10 using the posts_limit setting.

- Advanced Features: The plugin’s flexibility extends to more complex use cases. It can be configured to generate separate feeds for specific categories, tags, or even other content collections. For sites where full content syndication is not desired, an excerpt_only flag can be set to include only the post summary in the feed. It also supports sophisticated author management, allowing author information to be defined globally, on a per-post basis, or centrally in a _data/authors.yml file.

jekyll-paginate: Managing Content Archives and User Navigation

The jekyll-paginate plugin addresses the fundamental need for pagination on content-heavy sites, particularly blogs. It provides a mechanism to break up the main list of posts into multiple, digestible pages, improving user experience and site navigation.

- Purpose: Without pagination, a blog with hundreds of posts would present them all on a single, unwieldy page. This plugin automates the process of splitting this list into numbered pages.

- Installation and Usage: The plugin is enabled by adding it to the Gemfile and _config.yml. Two key settings are required in _config.yml: paginate, which defines the number of posts per page, and paginate_path, which specifies the URL structure for subsequent pages (e.g., /blog/page:num/).

- Implementation: To render the paginated content, a developer uses the paginator object that the plugin makes available to Liquid. In a file named index.html, one would loop through paginator.posts instead of site.posts. The plugin also provides variables like paginator.next_page_path, paginator.previous_page_path, and paginator.total_pages to build the “Next,” “Previous,” and page number navigation links.

- Limitations and Alternatives: The original jekyll-paginate plugin has significant limitations that are important to understand. It can only paginate the main site.posts collection; it does not support pagination for categories, tags, or other collections. Furthermore, it is designed to work only from a file named index.html. These constraints led the community to develop a more powerful successor, jekyll-paginate-v2. This alternative plugin supports pagination on any collection, filtering by category or tag, custom sorting, and more flexible naming for pagination templates. This evolution serves as a perfect microcosm of the Jekyll ecosystem: a simple core feature was eventually superseded by a more robust, community-driven solution. However, this creates a critical divergence for developers, as jekyll-paginate-v2 is not supported by the native GitHub Pages build environment, forcing those who need its advanced features to adopt a custom deployment workflow.

The GitHub Pages Constraint: Security, Safe Mode, and the Plugin Whitelist

GitHub Pages provides a powerful and convenient platform for hosting Jekyll sites for free. However, this convenience comes with a significant trade-off: a strict limitation on which Jekyll plugins can be used. This restriction is not arbitrary; it is a deliberate architectural and security decision rooted in the nature of GitHub Pages as a free, multi-tenant, shared hosting service. Understanding the rationale behind these constraints is crucial for any developer choosing to host a Jekyll site on the platform.

Understanding the Shared Environment: The Rationale Behind –safe Mode

GitHub Pages operates on a massive scale, building and serving millions of websites from a shared infrastructure. The platform’s primary mandate is to ensure the security, stability, and fair use of its resources for all users. The single greatest threat to this mandate is the potential for arbitrary code execution. A Jekyll plugin, at its core, is a piece of Ruby code that runs on GitHub’s servers during the site build process. If developers were allowed to run any plugin they wished, a malicious actor could easily upload a plugin designed to:

- Launch denial-of-service attacks against other websites.

- Use server resources for unauthorized activities like cryptocurrency mining.

- Attempt to access or steal data from the build environment or other users’ sites.

- Compromise the integrity of the GitHub Pages build servers.

To mitigate this fundamental security risk, GitHub Pages runs all Jekyll builds with the –safe command-line flag enabled. This is a built-in Jekyll feature specifically designed for environments where arbitrary code execution is not permissible. When active, –safe mode disables the loading of any custom plugins from the _plugins directory and restricts the use of symbolic links. This effectively sandboxes the build process, preventing unvetted code from running on GitHub’s infrastructure.

The github-pages Gem: A Curated, Version-Locked Build Environment

While –safe mode locks down the _plugins directory, GitHub recognized that a useful Jekyll environment requires a baseline of essential plugins. Their solution was to create and maintain the github-pages RubyGem. This gem serves as the definitive, canonical definition of the entire build environment used by the GitHub Pages service.

The github-pages gem is more than just a list of approved plugins; it is a comprehensive bundle of specific, version-locked dependencies. It dictates the exact version of Jekyll, as well as the exact versions of all whitelisted plugins and their own dependencies, that will be used to build a site. This approach provides two key benefits for the platform:

- Security: Every plugin included in the gem has been vetted by GitHub’s security team to ensure it does not pose a risk to the shared environment.

- Consistency: It guarantees a stable and reproducible build process. By encouraging developers to use the github-pages gem in their local Gemfile, it ensures that the site they preview on their own machine will be identical to the one built and deployed by GitHub, eliminating “it works on my machine” issues.

The trade-off for this stability and security is a loss of flexibility. Developers are locked into the specific versions of software that GitHub has approved, which often lag behind the latest releases available in the broader community. A new version of Jekyll or a popular plugin might not be available on GitHub Pages for weeks or months after its release, if ever.

The Official GitHub Pages Plugin Dependency List

The definitive answer to the question “What plugins can I use on GitHub Pages?” is found by examining the runtime dependencies of the github-pages gem itself. This is not a manually curated marketing list but the technical source of truth. Any plugin listed as a dependency of this gem is supported in the native GitHub Pages build environment.

The following table details the officially supported plugins as defined by a representative version (v228) of the github-pages gem. This list includes the essential plugins analyzed in Section 3, as well as others that provide GitHub-specific functionality and other common utilities.

| Plugin Name | Version | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| jekyll-avatar | 0.7.0 | Renders a user’s GitHub avatar. |

| jekyll-coffeescript | 1.1.1 | A converter for CoffeeScript files. |

| jekyll-commonmark-ghpages | 0.4.0 | A CommonMark converter with GitHub Flavored Markdown extensions. |

| jekyll-default-layout | 0.1.4 | Assigns a default layout to posts and pages without one. |

| jekyll-feed | 0.15.1 | Generates an Atom (RSS-like) feed of posts. |

| jekyll-gist | 1.5.0 | A Liquid tag for embedding GitHub Gists. |

| jekyll-github-metadata | 2.13.0 | Populates the site.github variable with repository metadata. |

| jekyll-include-cache | 0.2.1 | Caches includes to speed up build times. |

| jekyll-mentions | 1.6.0 | Converts @mention syntax to links to GitHub profiles. |

| jekyll-optional-front-matter | 0.3.2 | Allows pages to be processed without requiring YAML front matter. |

| jekyll-paginate | 1.1.0 | The original pagination generator for posts. |

| jekyll-readme-index | 0.3.0 | Renders the repository’s README.md as the site’s index page. |

| jekyll-redirect-from | 0.16.0 | Generates redirect pages for posts and pages. |

| jekyll-relative-links | 0.6.1 | Converts relative links to Markdown files into proper permalinks. |

| jekyll-remote-theme | 0.4.3 | Enables the use of Jekyll themes hosted in GitHub repositories. |

| jekyll-sass-converter | 1.5.2 | A converter for Sass and SCSS files. |

| jekyll-seo-tag | 2.8.0 | Generates a comprehensive set of SEO-related meta tags. |

| jekyll-sitemap | 1.4.0 | Generates a sitemaps.org-compliant sitemap. |

| jekyll-titles-from-headings | 0.5.3 | Automatically sets a page’s title from its first heading. |

| jemoji | 0.12.0 | Renders GitHub-flavored emoji. |

Source: github-pages gem, version 228

This strict, dependency-managed approach represents a classic “Platform vs. Flexibility” trade-off. GitHub has prioritized the integrity, security, and stability of its platform over the freedom of individual developers. This business and architectural decision has profoundly shaped the Jekyll deployment ecosystem, creating a clear bifurcation in the user base. Developers whose needs are met by the curated whitelist can enjoy the unparalleled simplicity of the native platform.

“`

Those with more advanced requirements must adopt strategies that treat GitHub Pages not as a Jekyll build service, but as a simple hosting target for pre-compiled static files.

Section 5: Modern Deployment Strategies for Custom Plugins on GitHub Pages

5.1 The Pre-Compilation Method: A Foundational (but Outdated) Approach

The original workaround for GitHub Pages’ plugin limitations was a manual pre-compilation process. The core concept is simple: since GitHub Pages will happily serve any static HTML, CSS, and JavaScript files, a developer can run the Jekyll build process on their local machine and then push the resulting static site to GitHub.

- Concept: The developer runs the

jekyll buildcommand locally. This command processes the entire Jekyll source and generates the complete, ready-to-deploy static site in a destination folder, typically named_site. The developer then commits and pushes only the contents of this_sitefolder to the branch that GitHub Pages is configured to serve from (e.g.,gh-pagesor themainbranch). - Workflow: This approach necessitates careful management of Git branches. A common pattern is to maintain the Jekyll source code on a development branch (e.g.,

sourceordevelop) and use themainorgh-pagesbranch exclusively for the compiled output. The developer works on the source branch, and when ready to deploy, they build the site, switch to the deployment branch, copy the contents of_siteover, and push the changes. - Drawbacks: While effective, this manual workflow is highly inefficient and prone to human error. It requires disciplined Git usage, clutters the repository’s history with generated build artifacts, and makes collaboration difficult, as each contributor must have a perfectly configured local Jekyll environment. For these reasons, the manual pre-compilation method is now considered a legacy approach, superseded by automated solutions.

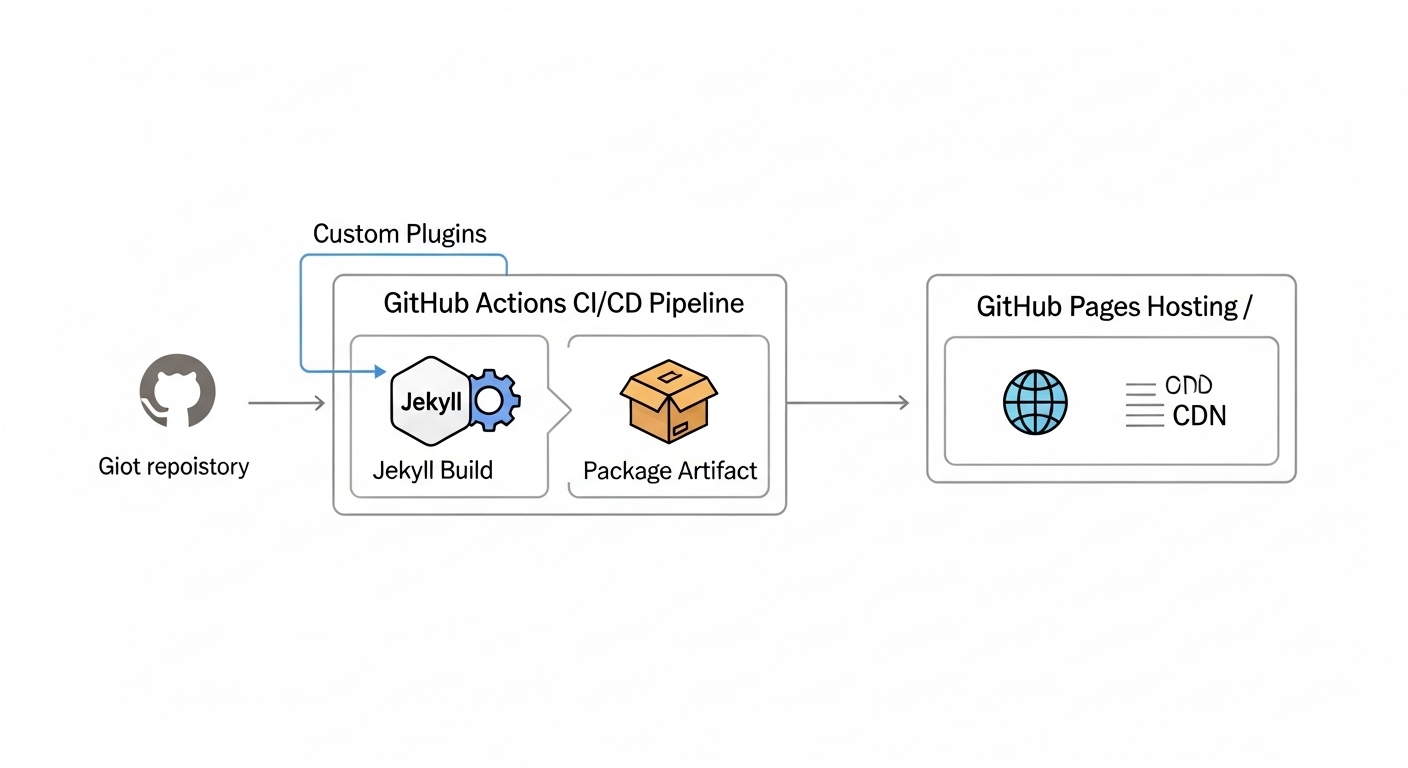

5.2 The CI/CD Paradigm: Automating Builds with GitHub Actions

The modern, recommended solution for deploying a Jekyll site with custom plugins to GitHub Pages is to use a CI/CD service to automate the entire build-and-deploy process. GitHub’s own integrated CI/CD product, GitHub Actions, has become the de facto standard for this task. This paradigm completely decouples the build process from the hosting platform. The developer pushes their Jekyll source code, and GitHub Actions automatically executes a series of predefined steps to build the site in a fully customizable environment and then deploy the static output to the GitHub Pages hosting infrastructure.

This approach represents a fundamental shift in how GitHub Pages is utilized. It evolves from an integrated “Jekyll-as-a-Service” platform into a pure “Static Hosting Target” that is agnostic to the build process. This change dramatically broadens its utility, as a developer can now use GitHub Actions to build a site with any static site generator—not just Jekyll—and deploy the output to GitHub Pages.

Comparative Analysis: Native Build vs. GitHub Actions Workflow

The choice between the native build process and a custom GitHub Actions workflow has significant implications for a project. The following table provides a side-by-side comparison of the two approaches across key criteria.

- Plugin Support:Native GitHub Pages Build: Restricted to a specific, whitelisted set of plugins.

GitHub Actions Workflow: Unrestricted. Any Jekyll plugin, including custom .rb files, can be used.

- Jekyll Version:Native GitHub Pages Build: Locked to the version specified in the

github-pagesgem.GitHub Actions Workflow: Full control. Any version of Jekyll can be specified in the

Gemfile. - Build Customization:Native GitHub Pages Build: Fixed build process with limited configuration options.

GitHub Actions Workflow: Highly customizable. Can include pre-build and post-build steps like asset minification, running tests, or fetching data from APIs.

- Debugging:Native GitHub Pages Build: Opaque build process. Errors can be difficult to diagnose.

GitHub Actions Workflow: Transparent. Provides detailed, verbose build logs for every step, simplifying troubleshooting.

- Build Speed:Native GitHub Pages Build: Generally fast for simple sites. No caching of dependencies.

GitHub Actions Workflow: Can be faster for complex sites due to caching of gem dependencies between builds.

- Setup Complexity:Native GitHub Pages Build: Zero configuration. Enabled by default.

GitHub Actions Workflow: Requires initial setup of a YAML workflow file in the repository.

Step-by-Step Implementation of a Jekyll Deployment Workflow

Setting up a GitHub Actions workflow for Jekyll is a straightforward process that turns the deployment logic into version-controlled code, a practice known as “infrastructure as code.”

- Repository Setup: The first step is to configure the repository’s GitHub Pages settings. Navigate to Settings > Pages. Under “Build and deployment,” change the “Source” from “Deploy from a branch” to “GitHub Actions”. This tells GitHub Pages to expect deployments from a workflow rather than building from a source branch.

- Workflow File Creation: In the root of the repository, create a directory structure

.github/workflows/. Inside this directory, create a new YAML file, for example,deploy.yml. GitHub provides a pre-configured Jekyll workflow template that serves as an excellent starting point. - Workflow Breakdown: The YAML workflow file defines the sequence of jobs and steps that GitHub Actions will execute. A typical Jekyll deployment workflow consists of the following key steps:

- Trigger (

on): Defines when the workflow should run. A common configuration ison: push: branches: ["main"], which triggers the workflow every time code is pushed to themainbranch. - Permissions: Sets the necessary permissions for the workflow to write to the GitHub Pages environment.

- Job Definition: A workflow is composed of one or more jobs. A standard Jekyll workflow has a build job and a deploy job.

- Build Steps:

actions/checkout@v: This action checks out the repository’s source code so the workflow can access it.ruby/setup-ruby@v: This action sets up the specified version of Ruby and, crucially, configures caching for Bundler. This means gems are downloaded and installed only once, and subsequent builds reuse the cached versions, significantly speeding up the process.bundle install: This command installs all the project dependencies defined in theGemfile.bundle exec jekyll build: This is the core command that builds the Jekyll site and outputs the static files to the_sitedirectory.actions/upload-pages-artifact@v: This action takes the contents of the_sitedirectory, packages it as an artifact, and uploads it for the deployment job to use.

- Deploy Step:

actions/deploy-pages@v: This final action takes the artifact uploaded by the build job and deploys it to the GitHub Pages hosting environment, making the site live.

- Trigger (

This version-controlled workflow file makes the entire deployment process transparent, reproducible, and robust, representing a massive leap forward from the opaque native build or the error-prone manual methods.

5.3 Alternative Hosting and Build Services

While GitHub Actions is the most integrated solution for deploying custom Jekyll sites to GitHub Pages, it is important to note that other platforms in the Jamstack ecosystem offer similar or even more streamlined experiences. Services like Netlify and CloudCannon provide first-class support for Jekyll and can connect directly to a GitHub repository. These platforms typically support any Jekyll plugin out-of-the-box without requiring the manual configuration of a CI/CD pipeline, as their build environments are inherently more flexible than the native GitHub Pages service. They represent excellent alternatives for developers seeking maximum flexibility with minimum setup complexity.

Section 6: Conclusion and Strategic Recommendations

The Jekyll plugin ecosystem provides a powerful and flexible architecture for extending the core functionality of the static site generator. Through a well-defined taxonomy of plugin types—including Generators, Converters, Tags, and Filters—developers can hook into virtually every stage of the build lifecycle to automate content creation, transform markup, and customize site output. This extensibility is central to Jekyll’s enduring appeal, allowing it to be adapted for a wide range of use cases, from simple personal blogs to complex documentation sites.

However, the unconstrained power of plugins presents a security challenge for shared hosting environments. GitHub Pages, as a free, multi-tenant platform, addresses this by running all builds in a sandboxed “safe mode” and restricting execution to a curated whitelist of vetted plugins. This policy, implemented through the version-locked github-pages gem, creates a fundamental dichotomy for developers.

6.1 Synthesizing the Trade-offs: Simplicity vs. Flexibility

The decision of how to build and deploy a Jekyll site on GitHub Pages hinges on a core trade-off between simplicity and flexibility.

- The Path of Simplicity: The native GitHub Pages build environment offers an unparalleled “push-to-deploy” experience.

It requires zero configuration and is the ideal choice for projects whose requirements can be fully met by the officially supported, whitelisted plugins. This path prioritizes ease of use and rapid deployment over custom functionality.

- The Path of Flexibility: The custom GitHub Actions workflow offers complete and unrestricted control over the build environment. It allows the use of any plugin, any version of Jekyll, and the integration of complex, multi-step build processes. This path prioritizes power and customization at the cost of a modest initial setup investment in creating a workflow file.

6.2 Recommendations for Project Scenarios

The optimal deployment strategy is dictated by the specific needs of the project. The following recommendations provide a clear decision framework:

- When to Use the Native GitHub Pages Environment:

- Personal Blogs and Simple Websites: For projects that primarily require content authoring and can leverage the core suite of whitelisted plugins (jekyll-seo-tag, jekyll-sitemap, jekyll-feed, jekyll-paginate), the native environment is the most efficient choice.

- Project Documentation: When the goal is to quickly generate documentation sites that do not require advanced features like custom data processing or asset pipelines.

- Beginner Projects: For developers new to Jekyll, the native workflow provides the shallowest learning curve and allows them to focus on content rather than deployment infrastructure.

- When to Use a Custom GitHub Actions Workflow:

- Projects Requiring Non-Whitelisted Plugins: This is the most common driver. If a project depends on a plugin not on the official list—such as the advanced jekyll-paginate-v2 for category pagination or jekyll-assets for an asset pipeline—a custom workflow is mandatory.

- Need for a Newer Jekyll Version: When a project needs to leverage features or bug fixes available only in a version of Jekyll more recent than the one bundled in the github-pages gem.

- Complex Build Requirements: For professional projects that require custom build steps, such as fetching data from an external API, running automated tests, or performing advanced image optimization before the Jekyll build.

- Professional and Collaborative Projects: The “infrastructure as code” approach of a version-controlled workflow file makes the deployment process transparent, reproducible, and robust, which are essential qualities for team-based development and long-term project maintainability.

6.3 The Future of Jekyll and Serverless Deployment

The standardization of the GitHub Actions workflow does more than just solve the plugin limitation; it firmly positions Jekyll within the modern Jamstack and serverless development paradigm. By decoupling the build process from the hosting environment, this model aligns Jekyll with contemporary best practices, where source code lives in a Git repository, and a CI/CD pipeline automates the process of building and deploying immutable static assets to a global content delivery network (CDN). This ensures that Jekyll, despite its maturity, remains a relevant, high-performance, and strategically sound choice for building fast, secure, and scalable websites.

📚 For more insights, check out our complete web development guide.