Mastering SEO Permalinks & URL Structure for Better Rankings

Section 1: The Anatomy of a URL: Understanding Permalinks, Slugs, and Their Strategic Value

In the architecture of the modern web, the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) serves as the fundamental addressing system, enabling navigation and resource identification. Within this system, the concept of a “permalink” represents a critical evolution from a simple address to a strategic asset. This section deconstructs the components of a URL, defines the permalink, and establishes its foundational importance in creating a stable, understandable, and trustworthy digital presence.

1.1 Defining the Permalink: The Digital Address of Content

A permalink, a portmanteau of “permanent link,” is the static and unchanging URL assigned to a specific piece of online content. Every individual post, page, category archive, or other distinct resource on a website has its own unique permalink. For example, a website’s homepage might be https://example.com/, while a specific blog post resides at https://example.com/blog/seo-best-practices/. The defining characteristic of a permalink is its permanence; it is designed to remain a consistent address for its associated content indefinitely, ensuring that links shared across the web do not become broken over time.

While every permalink is a URL, not every URL is a permalink. A URL is a general web address that can be static or dynamic, permanent or temporary. A permalink, however, specifically refers to the permanent URL structure intended for long-term content sharing and indexing. This distinction is vital for understanding the architectural choices that underpin a durable web presence.

A permalink is composed of several key parts:

- Protocol: Typically https (Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure), which indicates a secure connection.

- Domain Name: The primary address of the website, such as example.com.

- Path: The directory structure that organizes content, for example, /blog/ or /services/.

- Slug: The final, unique part of the URL that identifies the specific page or post. In the URL https://kinsta.com/blog/wordpress-widgets/, the slug is wordpress-widgets. The slug is automatically generated from the content’s title but can and should be manually optimized.

This concept of permanence establishes a permalink not merely as a technical address but as a form of digital contract. When a URL is created, shared, bookmarked, or linked to by another website, an implicit promise of stability is made to both users and other web platforms. A user who discovers a link in an old email or a researcher following a citation expects the resource to be accessible. Search engines that have indexed a page and assigned it authority through backlinks expect to find it at the same address. Changing a permalink without proper redirection protocols breaks this contract, resulting in a 404 “Not Found” error. This failure erodes user trust, invalidates social shares, and, most critically, severs the pathways of authority (link equity) that are the foundation of search engine rankings. Therefore, the initial selection of a permalink structure is a long-term architectural commitment with significant consequences for a brand’s digital reliability and authority.

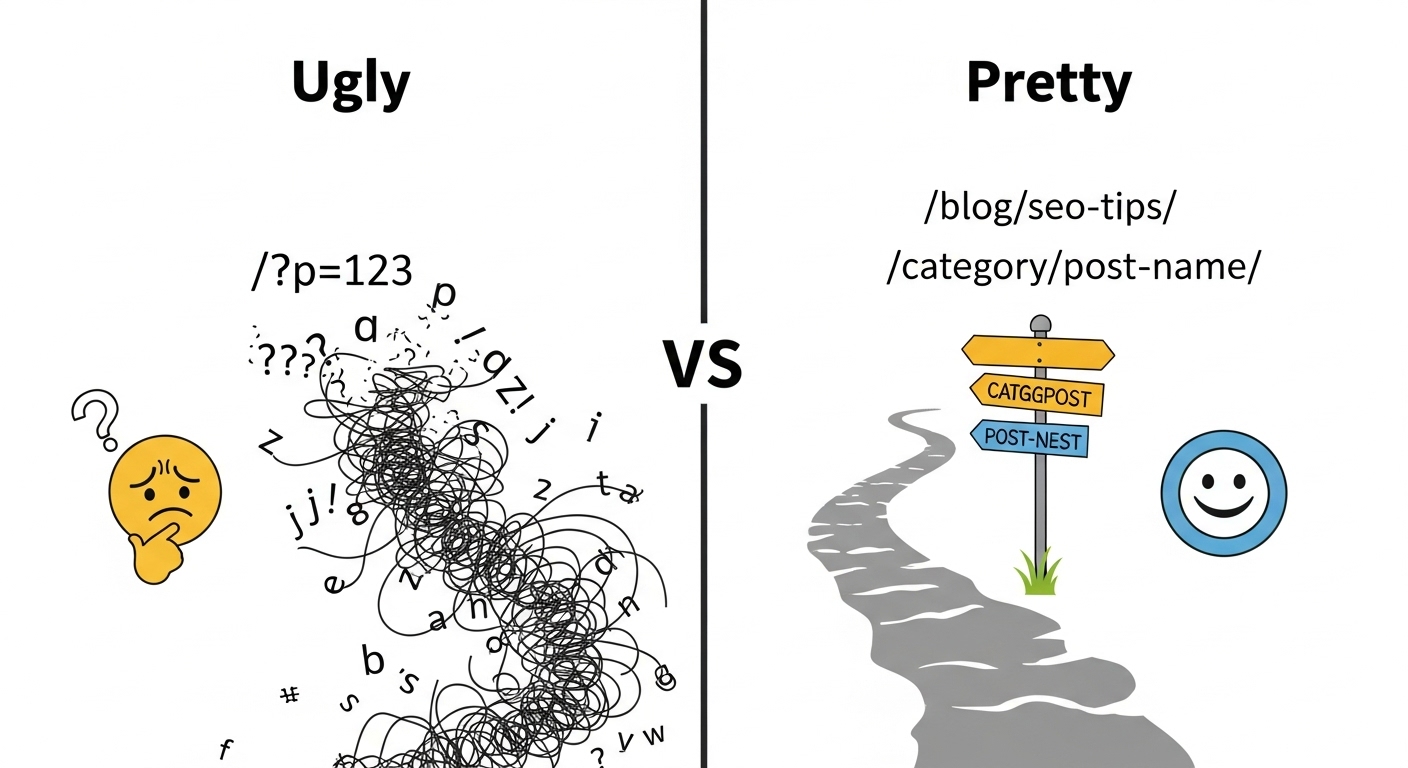

1.2 The Spectrum of URL Structures: From “Ugly” to “Pretty”

URL structures exist on a spectrum of readability and semantic value, ranging from machine-generated “ugly” links to human-readable “pretty” links.

- “Ugly” Permalinks (Default/Plain): These are the default structures in many content management systems (CMS) upon initial installation. They are programmatically generated and rely on query strings to pull content from a database, using parameters like a post’s unique ID. An example is http://example.com/?p=123. While functionally capable of retrieving content, these URLs provide no contextual information to humans or search engines and are considered detrimental to both user experience and SEO.

- “Almost Pretty” Permalinks: This is an intermediate structure that often includes the script name index.php within the URL path, such as http://example.com/index.php/2024/05/13/post-name/. It represents an improvement over ugly permalinks by incorporating descriptive words but is still considered suboptimal due to its unnecessary length and technical artifacts.

- “Pretty” Permalinks: These are the industry standard for modern websites. They are intentionally structured to be readable, descriptive, and optimized for search engines. By using a logical path and a keyword-rich slug, a pretty permalink like http://example.com/blog/seo-tips/ clearly communicates the content’s topic to both users and search engine crawlers.

1.3 Static vs. Dynamic URLs: A Key Architectural Distinction

The nature of a URL—whether it is static or dynamic—is another critical architectural consideration with direct implications for SEO and usability.

- Static Permalinks: A static permalink is fixed and does not change. It points to a specific piece of content, such as a blog post, an “About Us” page, or a service page. Their stability and descriptive nature are favored by search engines, as they provide a reliable and clear signal about the content’s topic and location.

- Dynamic URLs: In contrast, a dynamic URL is generated on the fly and changes based on user interactions, database queries, or other parameters. They are common on e-commerce sites for filtering products (e.g., by color or size) or on platforms with extensive user-generated content. An example might be example.com/products?category=shoes&color=blue. While essential for certain functionalities, dynamic URLs can pose significant SEO challenges. They can lead to a proliferation of near-identical pages (duplicate content), which dilutes ranking signals and consumes a search engine’s crawl budget inefficiently. These issues are typically managed through the use of canonical tags, which specify the preferred version of a URL for indexing purposes.

Section 2: The Symbiotic Relationship Between URL Structure, SEO, and User Experience

A well-architected permalink structure is not merely a technical best practice; it is a cornerstone of a successful digital strategy. Its impact extends across Search Engine Optimization (SEO) and User Experience (UX), creating a symbiotic relationship where optimizations for one domain invariably benefit the other. The URL is a fundamental signal used by both machines and humans to interpret and evaluate web content.

2.1 Permalinks as a Search Engine Ranking Factor

Search engines like Google use a multitude of signals to rank pages, and the URL structure itself is a recognized, albeit moderate, ranking factor. Its influence is multifaceted, affecting relevance, crawlability, and user behavior signals.

- Content Relevance Signal: The words within a URL are a direct signal to search engines about the page’s topic. Including the primary keyword in the slug reinforces the page’s relevance for that search term. One analysis of Google ranking factors identified the presence of a keyword in the URL as the 55th most important signal, highlighting its role in contextual understanding.

- Crawlability and Indexing: A logical, hierarchical URL structure (e.g., …/category/post-name/) helps search engine crawlers understand the architecture of a site and the relationships between different pieces of content. This clear organization facilitates more efficient crawling and indexing. Conversely, complex, parameter-laden dynamic URLs can create challenges for crawlers, potentially leading to an incomplete index of the site’s content.

- Click-Through Rate (CTR) from SERPs: In a list of search engine results, a clean, descriptive URL is more appealing to users and can significantly improve CTR. A URL that clearly reflects the page’s content allows users to predict its relevance to their query before clicking, increasing the likelihood that they will choose that result over one with a cryptic or generic URL.

- Link Equity: Clean, professional-looking URLs are more likely to be trusted and shared, thereby attracting more backlinks from other websites. Since backlinks are a primary driver of SEO authority, a URL structure that encourages their acquisition is inherently valuable.

The URL is, in effect, a micro-marketing message. It is often the most concise and portable piece of marketing copy a page possesses. When a link is shared on social media, pasted into a plaintext email, or displayed in a browser tab, the URL may be the only available context. A well-structured URL like brand.com/resources/complete-guide-to-permalinks acts as a powerful, self-contained advertisement. It communicates the brand (brand.com), the content type (resources), the topic (permalinks), and the value proposition (complete-guide). In contrast, a URL like brand.com/?p=123 communicates nothing and can appear untrustworthy, deterring clicks and shares. Optimizing a permalink is therefore not just a technical SEO task; it is the act of crafting a potent marketing asset that functions across multiple channels.

2.2 Enhancing User Experience (UX) and Trust

The same characteristics that make a permalink valuable for SEO also enhance the experience for human users.

A user-centric URL structure fosters trust, improves navigability, and sets clear expectations.

-

Readability and Memorability: Simple, semantic URLs are easy for users to read, understand, and remember. A user is far more likely to recall and manually type example.com/contact than example.com/index.php?page_id=2.

-

Setting Expectations: A well-crafted permalink provides a clear preview of the page’s content, helping users make informed decisions about which links to follow. This transparency reduces user frustration and lowers bounce rates, as visitors are more likely to land on a page that meets their expectations.

-

Shareability: Clean URLs are easily copied and pasted into social media posts, emails, and messaging applications without appearing spammy or breaking due to special characters. This facilitates the organic spread of content.

-

Navigational Hierarchy (“Hacking” URLs): A logical folder structure within the URL, such as example.com/services/web-design/, empowers users to navigate the site’s hierarchy intuitively. By deleting the final segment of the URL (a practice known as “URL hacking”), a user can easily move up to the parent services category page. This provides a predictable and efficient method of site exploration, a key principle of good usability.

Section 3: A Comparative Analysis of Permalink Structures in WordPress

WordPress, as the world’s most popular CMS, provides a powerful yet straightforward interface for controlling URL architecture. The choices made within its Settings → Permalinks screen are foundational and have long-term consequences for a site’s SEO and usability. It is critical to establish an optimal structure at the outset of a project, as changing it on an established site introduces significant risks and technical complexity. This section provides a detailed analysis of the default and custom permalink options available in WordPress to guide this crucial decision.

3.1 Overview of WordPress Permalink Settings

The WordPress dashboard offers a dedicated settings panel for managing the site-wide permalink structure. This panel presents several predefined options and a field for creating a custom structure using specific tags. This initial configuration dictates the template for all future post and page URLs, making it one of the most important settings for a new website.

3.2 Deconstructing the Default Options

WordPress offers several out-of-the-box permalink structures, each with distinct advantages and disadvantages.

-

Plain (/?p=123): This is the default setting on a fresh WordPress installation. It uses the post’s unique ID from the database as a query parameter.

-

Pros: It is guaranteed to work on any server environment without requiring special configurations like Apache’s mod_rewrite module.

-

Cons: This structure is completely opaque to both users and search engines. It offers zero SEO value, is not user-friendly, looks unprofessional, and is strongly discouraged for any modern website.

-

-

Day and Name (/2024/05/13/sample-post/): This structure includes the full publication date (year, month, and day) in the URL, followed by the post slug.

-

Pros: It is highly effective for time-sensitive content, such as news websites or publications that release multiple articles daily. The date provides immediate context about the content’s timeliness.

-

Cons: The primary drawback is that it makes “evergreen” content appear dated. A user searching for a guide in 2024 might be hesitant to click a link with “2021” in the URL, even if the content is still relevant. It also creates unnecessarily long URLs.

-

-

Month and Name (/2024/05/sample-post/): This is a slightly more concise version of the “Day and Name” structure, omitting the day.

-

Pros: Similar to the above, it is suitable for date-driven content while creating a marginally shorter URL.

-

Cons: It shares the same fundamental issue of making evergreen content appear outdated and adds unnecessary length to the URL.

-

-

Numeric (/archives/123): This structure uses the post’s ID, prefixed with an /archives/ segment.

-

Pros: The URLs are relatively compact.

-

Cons: Like the “Plain” option, it provides no descriptive information about the content. The /archives/ prefix can further reinforce the perception of outdated material, making it a poor choice for both SEO and user experience.

-

-

Post Name (/sample-post/): This structure uses only the post slug after the domain name.

-

Pros: This is the most widely recommended structure for the vast majority of websites. It creates short, clean, memorable, and highly descriptive URLs. It focuses the URL entirely on the content’s title and primary keyword, maximizing its SEO impact.

-

Cons: There is a minor theoretical risk of URL conflicts if two posts have the exact same title (and thus the same default slug), but WordPress automatically prevents this by appending a number (e.g., /sample-post-2/).

-

3.3 The Power of Custom Structures

For sites with complex content hierarchies, WordPress offers the ability to create a custom permalink structure using a set of predefined tags.

Common tags include:

-

%postname%: The post’s slug.

-

%category%: The primary category of the post.

-

%author%: The author’s name.

-

%year%, %monthnum%, %day%: Date components.

-

%post_id%: The post’s unique ID.

A popular and effective custom structure is /%category%/%postname%/. This format creates a clear, hierarchical URL like example.com/technology/new-smartphone-review/. This approach is excellent for large blogs or informational sites, as it helps organize content logically and provides strong contextual signals to both users and search engines about the site’s structure. However, care must be taken to ensure that category names are concise to avoid creating overly long or deeply nested URLs, which can harm readability and usability.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Default WordPress Permalink Structures

Section 4: The Blueprint for Optimal URLs: A Synthesis of SEO Best Practices

Constructing an optimal URL is a deliberate process that balances technical requirements, SEO strategy, and user psychology. A well-formed URL serves as a clear, concise descriptor of its destination page. This section synthesizes authoritative best practices from search engine documentation and industry experts into a comprehensive blueprint for creating SEO-friendly permalinks.

4.1 Core Principles of an SEO-Friendly URL

At its heart, an effective URL is simple, descriptive, and focused. Adhering to these core principles ensures that the URL serves its dual purpose of informing search engines and guiding users.

-

Be Descriptive and Relevant: The URL must accurately describe the content of the page. The words used should be easily understood by the target audience and reflect the language they use in their searches. A URL like …/organic-herbal-tea is far more effective than …/item-8721.

-

Incorporate Keywords Strategically: The primary keyword for the page should be included in the slug, ideally near the beginning to give it prominence. However, this should be done naturally. Overloading the URL with keywords, known as keyword stuffing, can make it appear spammy to both users and search engines and should be avoided.

-

Prioritize Brevity and Simplicity: Shorter URLs are generally better. They are easier to read, remember, and share, and they tend to perform better in search rankings. A common guideline is to aim for a slug of three to five words or a total URL length of under 60 characters. To achieve this, it is often beneficial to remove unnecessary “stop words” such as ‘a’, ‘an’, ‘the’, ‘of’, and ‘in’, unless they are essential for clarity.

4.2 Technical and Formatting Requirements

Proper formatting is crucial for ensuring that URLs are correctly interpreted by servers, browsers, and search engine crawlers.

-

Use Hyphens as Separators: Hyphens are the universally accepted standard for separating words in a URL. Google’s crawlers are programmed to interpret hyphens as spaces, allowing them to parse individual words and keywords correctly. Underscores (_), in contrast, are often interpreted as word joiners, causing a phrase like seo_best_practices to be read as a single, nonsensical word, which negates its keyword value.

-

Maintain Lowercase: URLs are case-sensitive on many servers. Using a mix of uppercase and lowercase letters can lead to 404 errors or, more insidiously, create duplicate content issues where …/My-Page and …/my-page are seen as two distinct URLs with identical content. Adhering strictly to lowercase letters is the safest and most consistent approach.

-

Avoid Unsafe Characters: URLs should only contain standard, unreserved characters. Special characters such as #, <, >, %, {}, “, and spaces must be percent-encoded to be valid, which makes the URL cluttered and difficult to read. Sticking to alphanumeric characters and hyphens is the best practice.

-

HTTPS is Non-Negotiable: All modern URLs should use the https:// protocol. HTTPS encrypts data between the user’s browser and the server, which is essential for security and user trust. It is also a confirmed, albeit minor, Google ranking signal.

4.3 Structural Best Practices

Beyond the individual URL, the overall structure of a site’s URLs should create a logical and intuitive hierarchy.

A URL like example.com/services/seo/technical-seo clearly indicates the page’s position within the site’s architecture, aiding both user navigation and search engine understanding of topical relationships.

- Avoid Excessive Nesting: While a hierarchical structure is beneficial, it should be kept relatively shallow. URLs with too many subdirectories (e.g., …/blog/2024/marketing/seo/guides/post-name) become long, difficult to read, and can dilute the perceived importance of the page. A structure that is one or two levels deep is generally optimal.

- Avoid Dates and Numbers (for Evergreen Content): For content that is intended to be relevant over a long period, including a date in the URL is a significant mistake. It instantly dates the content and can deter users from clicking on it in the future. Similarly, using arbitrary numbers or database IDs in the slug provides no value and should be avoided unless absolutely necessary (e.g., for product SKUs in a non-user-facing context).

Table 2: SEO-Friendly URL Pre-Publication Checklist

Checkpoint

- Keyword Usage

- Length & Brevity

- Word Separators

- Case

- Character Set

- Stop Words

- Dates/Numbers

- Hierarchy

Section 5: The Engine Room: Deconstructing the WordPress Routing and Request Process

To gain full control over URLs, it is essential to understand the underlying mechanics of how a web application processes a URL request and maps it to the correct content. This process, known as routing, is the engine that powers navigation. While modern web frameworks often use a direct routing system, WordPress employs a more intricate, translation-based mechanism that relies on a symbiotic relationship between the web server, a configuration file (.htaccess), and its internal Rewrite API. This section provides a detailed, step-by-step deconstruction of this process.

5.1 Introduction to Web Routing

At its core, routing is the mechanism that directs an incoming HTTP request to the specific code responsible for handling it. When a user enters a URL into their browser, the server-side routing system analyzes the URL’s path to determine which content or function to deliver. In traditional multi-page applications like those built on WordPress, this is a server-side process that results in the server sending a complete HTML document back to the browser for rendering.

A fundamental architectural distinction exists between how different systems handle this mapping. Many modern frameworks like Laravel or Express use a system of direction, where a URL pattern is explicitly mapped to a specific controller or function that executes a response. For example, a route might be defined as Route::get(‘/products/{id}’, ‘ProductController@show’), directly telling the application to run the show method in the ProductController when a matching URL is requested.

WordPress, however, operates on a system of translation. It does not directly map a pretty URL to a piece of code. Instead, it translates the human-readable “pretty” URL into an internal, machine-readable “ugly” URL with query parameters. This translated query then implicitly determines which content to fetch from the database. This architectural difference explains many of WordPress’s unique behaviors, such as the need to “flush” rewrite rules, and underscores its origin as a content-centric platform rather than an application framework.

5.2 The WordPress Request Lifecycle: A Step-by-Step Journey

The journey from a user entering a “pretty” permalink to viewing a rendered page in WordPress involves a precise sequence of events.

- Step 1: The Web Server Intercepts the Request (Apache & .htaccess) When a request for a pretty permalink like https://example.com/sample-post/ arrives at an Apache web server, the server initially finds that no file or directory exists at that path. This is where the .htaccess file becomes critical. This configuration file contains directives for the mod_rewrite module, which is responsible for URL rewriting. The standard WordPress .htaccess rules check if the requested filename is not an existing file (RewriteCond %{REQUEST_FILENAME}!-f) and not an existing directory (RewriteCond %{REQUEST_FILENAME}!-d). If both conditions are true, the RewriteRule directive funnels the entire request to a single point of entry: the index.php file in the WordPress root directory. This crucial step transforms the web server from a simple file server into a gateway for the WordPress application.

- Step 2: WordPress Boots Up (index.php → wp-blog-header.php → wp-load.php) The index.php file is the main entry point for all front-end requests. Its primary job is to load the WordPress environment. It does this by requiring wp-blog-header.php, which in turn loads wp-load.php. This file then includes wp-config.php to establish database credentials and other core settings, followed by wp-settings.php, which loads the bulk of the WordPress core functions, active plugins, and the active theme’s functions.php file. At the end of this stage, the entire WordPress application is loaded and ready to process the request.

- Step 3: Parsing the Request (The WP Class and the Rewrite API) With the environment loaded, control is passed to the main WP class. Its main() method initiates the request parsing process by calling the parse_request() method. This is the core of the routing mechanism. WordPress takes the original “pretty” URL string that was passed to index.php and compares it against a comprehensive list of “rewrite rules”.

- Step 4: The Rewrite API in Action The WordPress Rewrite API is the set of functions and filters that manage these rewrite rules. A rewrite rule is essentially a key-value pair, where the key is a regular expression (regex) that matches a URL pattern, and the value is the corresponding “ugly” URL with query variables. For example, a rule might match the pattern ^sample-post/?$ and translate it to index.php?name=sample-post. These rules are generated based on the permalink settings and any custom rules added by plugins or themes using functions like add_rewrite_rule(). For performance reasons, this master list of rules is stored (cached) in the database. This is why any changes to the permalink structure or custom rules require the rules to be “flushed”—a process that regenerates and saves the entire list to the database.

- Step 5: Building the Database Query (WP_Query) Once the Rewrite API finds a matching rule and generates the query string (e.g., name=sample-post), these query variables are used to populate the main WP_Query object. This powerful class is responsible for constructing and executing the final SQL query to retrieve the appropriate content from the wp_posts table in the database. The query variables directly control what is fetched—whether it’s a single post by its slug, an archive of posts from a specific category, or a static page.

- Step 6: Selecting the Template After WP_Query has successfully retrieved the content from the database, it sets various conditional flags (e.g., is_single(), is_page(), is_category()). The final step in the lifecycle is for the WordPress template loader to use these flags to determine which template file from the active theme should be used to render the page. It follows a specific template hierarchy, looking for the most specific template first (e.g., single-sample-post.php), then falling back to more general ones (e.g., single.php, and finally index.php) until a match is found. The selected template then uses the data from WP_Query to generate the final HTML, which is sent back to the user’s browser.

Section 6: Navigating Change: A Strategic Guide to Modifying Permalinks on an Established Website

The term “permalink” contains an implicit promise of permanence. However, strategic pivots, site redesigns, or the correction of a suboptimal initial setup may necessitate changing the URL structure of an established website. This is a high-stakes operation that, if handled improperly, can have devastating consequences for a site’s search engine visibility and user experience. This section provides a comprehensive playbook for managing this change, detailing the risks involved and the critical procedures for mitigating them through the correct implementation of 301 redirects.

6.1 The High Cost of Broken Links: Why Changing Permalinks is Risky

Changing a URL on a live website fundamentally breaks the web. Every existing link—whether internal from other pages on the site, external from backlinks, or shared on social media—will instantly point to a non-existent location, resulting in a 404 “Not Found” error. The cascading effects of this are severe.

- SEO Consequences:

- Loss of Link Equity: Backlinks from other authoritative websites are a primary driver of search engine rankings. When a URL changes without a redirect, the accumulated value, or “link equity,” from all backlinks pointing to that old URL is completely lost. Even with a proper permanent redirect, there is a historical belief among SEO professionals that a small amount of PageRank may be diluted in the process, though Google has indicated that this loss is now minimal or non-existent for 301s.

- Wasted Crawl Budget: Search engine crawlers have a finite amount of resources (a “crawl budget”) to spend on any given site. When they repeatedly encounter 404 errors or have to process long chains of redirects, this budget is wasted on non-productive tasks, which can delay the discovery and indexing of new, valuable content.

- Ranking Fluctuations and De-indexing: When a URL changes, Google must crawl the new URL and re-evaluate its content and signals from scratch.

This re-indexing process can lead to temporary, and sometimes permanent, fluctuations or drops in search rankings. If redirects are not implemented, Google will eventually de-index the old URL, removing it from search results entirely.

User Experience and Business Impact

-

User Frustration: Encountering a 404 error is a jarring and frustrating experience for users, often leading them to abandon the site (a high bounce rate) and seek information elsewhere.

-

Broken Marketing Channels: All previously shared links in email marketing campaigns, social media posts, paid ad campaigns, and referral traffic sources will become dead ends. This not only creates a poor user experience but also negates the value and investment of past marketing efforts.

6.2 The Solution: Mastering the 301 Redirect

The essential tool for mitigating the risks of changing permalinks is the 301 redirect. A 301 is an HTTP status code that signals to browsers and search engines that a page has permanently moved to a new location. When a server issues a 301 redirect, it instructs the client to update its records and automatically forwards the user to the new URL. Crucially, it also tells search engines to transfer the vast majority of the link equity and ranking signals from the old URL to the new one, thereby preserving SEO value.

6.3 A Step-by-Step Guide to Safely Changing Permalinks

A successful permalink migration requires careful planning, precise execution, and thorough verification.

-

Step 1: Pre-Change Preparation

-

Full Site Backup: The first and most critical step is to perform a complete backup of the website’s files and database. This provides a safety net in case of any unforeseen errors during the process.

-

Crawl and Map URLs: Use a website crawling tool (e.g., Screaming Frog) to generate a complete list of all existing URLs on the site. This spreadsheet will serve as a master map, documenting every old URL that will need to be redirected to its new counterpart.

-

Finalize the New Structure: Decide definitively on the new permalink structure. This decision should be based on the best practices outlined in Section 4. The migration process is not a time for experimentation.

-

-

Step 2: Implementation

-

Change the Permalink Setting: In the WordPress dashboard, navigate to Settings → Permalinks. Select the desired new structure (e.g., “Post Name”) and save the changes. This action will immediately update the URL structure for all content across the site. At this point, all external links and bookmarks will be broken until redirects are in place.

-

-

Step 3: Implementing 301 Redirects

There are two primary methods for implementing 301 redirects in a WordPress environment. The choice depends on the user’s technical proficiency and the scale of the migration.

-

Method A: Using a Plugin (Recommended for Most Users):

Dedicated redirection plugins offer a user-friendly interface for managing redirects without directly editing server files.

-

Install a Plugin: Install and activate a reputable plugin such as Redirection, or use the built-in redirect manager of a comprehensive SEO suite like AIOSEO or Yoast SEO Premium.

-

Configure Redirects: Many of these plugins can automatically monitor for permalink changes and create the necessary redirects. For manual setup, the interface typically requires two fields: the Source URL (the old relative path, e.g., /2023/01/my-post/) and the Target URL (the new, full URL, e.g., https://example.com/my-post/).

-

-

Method B: Manual .htaccess Configuration (For Advanced Users):

Directly editing the .htaccess file is a powerful and highly efficient method, especially for site-wide structural changes.

-

Access .htaccess: Connect to the server via an FTP client or a cPanel File Manager and locate the .htaccess file in the website’s root directory.

-

Add Redirect Rules: Add the appropriate redirect directives to the file. For changing from a date-based structure to a post-name structure, a single RedirectMatch rule using regular expressions can handle all posts simultaneously, which is far more efficient than creating individual redirects.

-

Example (Day and Name to Post Name):

RedirectMatch 301 ^/({4})/({2})/({2})/(.*)$ https://yourdomain.com/$4 -

Example (Month and Name to Post Name):

RedirectMatch 301 ^/({4})/({2})/(.*)$ https://yourdomain.com/$3

-

-

-

-

Step 4: Post-Change Verification

-

Test Redirects: Use the previously created URL map to test a significant sample of old URLs. Verify that they correctly 301 redirect to their new destinations.

-

Update Internal Links: While the redirects will handle traffic from old internal links, it is a best practice to update these links to point directly to the new URLs. This avoids unnecessary redirect hops, which can slightly impact page load speed and user experience.

-

Monitor 404 Errors: Use Google Search Console’s Coverage report and 404 monitoring plugins to identify any broken links that were missed during the migration process and create redirects for them.

-

Submit a New Sitemap: Generate a new XML sitemap containing all the new URLs and submit it to Google Search Console to encourage faster discovery and re-indexing of the updated site structure.

-

Table 3: 301 Redirect Implementation Methods Comparison

| Method | WordPress Plugin | Manual .htaccess Edit | Server-Level Config |

|---|

Conclusion

The architecture of a website’s URLs, governed by its permalink structure and routing mechanisms, is a foundational element of its digital identity. This report has established that the URL is far more than a simple address; it is a strategic asset that directly influences search engine optimization, user experience, brand perception, and the long-term stability of a web property.

The analysis reveals a clear consensus: a “pretty” permalink structure, characterized by its brevity, descriptive nature, and logical hierarchy, is the undisputed standard for modern web development. The widely recommended /%postname%/ structure offers an optimal balance of simplicity and SEO efficacy for the majority of websites, while custom structures like /%category%/%postname%/ provide necessary organizational depth for larger, content-rich platforms. The initial choice of this structure is a critical, long-term commitment, as the risks and complexities associated with changing it on an established site are substantial.

Delving into the technical underpinnings of WordPress, it becomes evident that its routing system is a sophisticated translation engine. It leverages the web server’s .htaccess file and its internal Rewrite API to convert human-readable URLs into machine-readable database queries. Understanding this step-by-step process—from server interception to template rendering—is essential for developers and technical SEOs seeking to troubleshoot issues or extend the platform’s capabilities.

Finally, for those facing the necessary task of modifying an existing permalink structure, a disciplined and methodical approach is paramount. The strategic use of 301 redirects is not merely a best practice but an absolute requirement to preserve hard-won link equity, maintain user trust, and prevent catastrophic losses in search visibility. By following a rigorous process of planning, implementation, and verification, the inherent risks of such a migration can be effectively managed.

Ultimately, taking full control of a website’s URLs requires a holistic understanding that bridges high-level strategy with low-level technical execution. By architecting permalinks with intention and managing them with precision, webmasters can build a more stable, visible, and user-friendly presence on the web.

📚 For more insights, check out our SEO best practices.