Pricing Psychology: Decoy Effect, Bundling & Behavioral Economics

Section 1: The Psychological Foundations of Price Perception

1.1 Beyond Cost-Plus: Defining Psychological Pricing

In the conventional economic model, price is a straightforward function of supply, demand, and production costs. However, this view fails to capture a crucial dimension of commerce: the human element. Psychological pricing is a strategic framework built on the theory that certain prices exert a distinct psychological impact, influencing consumer perception and purchasing decisions in ways that transcend rational calculation. It is a discipline that moves beyond the balance sheet to operate within the cognitive and emotional landscape of the consumer.

The core objective of psychological pricing is not merely to cover costs or match competitors but to shape how customers feel about a price. It leverages an understanding of human psychology to frame a price in the most attractive light possible, tapping into unspoken consumer desires: to secure the best deal, receive the best value, and choose the best quality. By presenting prices in specific ways—such as expressing them as just-below numbers like $19.99 or bundling multiple items into a single package—businesses can subtly guide consumer behavior, enhance the perceived value of their offerings, and ultimately drive sales and profitability.

This strategic approach recognizes that the consumer’s perception of price is more significant than the actual monetary value. It is an exercise in applied psychology, transforming pricing from a simple accounting function into a sophisticated tool for shaping the customer’s decision-making process. The most effective pricing strategies are not developed by finance departments in isolation but are crafted by strategists who understand and can build the consumer’s “choice architecture”—the context in which decisions are made. This reframes the entire discipline from a financial calculation to a strategic design problem rooted in behavioral science.

1.2 The Predictably Irrational Consumer: Key Behavioral Economics Concepts

The efficacy of psychological pricing is rooted in the principles of behavioral economics, a field that demonstrates how economic decisions are systematically influenced by psychological, social, cognitive, and emotional factors. The traditional assumption of a perfectly rational consumer who makes optimal choices based on complete information has been consistently challenged by research showing that human behavior is often, and predictably, irrational. Several foundational cognitive biases and principles underpin the strategies of psychological pricing.

- Anchoring Bias: This is the tendency for individuals to rely heavily on the first piece of information they receive (the “anchor”) when making decisions. In pricing, a high initial price can serve as an anchor, making subsequent, lower prices seem far more reasonable and attractive by comparison. For instance, a subscription service might first display a fully-featured enterprise plan for $500 per month. When the consumer then sees the business plan for $150 per month, that price is evaluated relative to the $500 anchor, making it appear to be a bargain, even if it might have seemed expensive in isolation.

- Loss Aversion: First proposed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, loss aversion describes the human tendency to feel the pain of a loss more acutely than the pleasure of an equivalent gain. Studies suggest the psychological impact of a loss is roughly twice as powerful as that of a gain. This principle is a potent motivator in marketing. Pricing strategies often frame offers to highlight a potential loss if the consumer fails to act, such as “Don’t miss out on 50% savings!” or through limited-time offers that create a sense of urgency and fear of missing out (FOMO).

- Choice Architecture: This concept refers to the practice of organizing the context in which people make decisions to “nudge” them toward certain choices without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. The design of a pricing page—the number of options, their order, the visual emphasis on a particular tier—is a form of choice architecture. It doesn’t force a consumer’s hand but makes one path feel more natural, logical, or attractive than others.

- Heuristics: When faced with complex decisions, consumers often rely on mental shortcuts, or heuristics, to simplify the process. Psychological pricing tactics are designed to align with these shortcuts. For example, the heuristic that “a higher price equals higher quality” is the foundation of prestige pricing, where luxury brands set high prices to signal exclusivity and superior craftsmanship. Conversely, charm pricing ($9.99) leverages the heuristic of focusing on the leftmost digit, simplifying the price to “$9 and something”. These heuristics allow for faster, if not always perfectly rational, decision-making.

1.3 The Primacy of Relative Value

A fundamental principle that unifies these cognitive biases is that human beings are far better at making relative judgments than absolute ones. Most consumers do not possess an innate, absolute sense of what a product or service should cost. Is a cup of coffee worth $5? Is a software subscription worth $50 per month? The answers are rarely clear in a vacuum. Instead, value is determined through comparison. We assess the fairness of a price by comparing it to other available options, to past prices, or to the prices of similar goods.

This reliance on relative comparison is the bedrock upon which many of the most powerful psychological pricing strategies are built. Marketers and pricing strategists understand that by controlling the context and the points of comparison, they can profoundly influence the perception of value. They can introduce a new option not because they expect it to sell, but because its very presence changes the relative attractiveness of the other options. This manipulation of the choice set is the core mechanism of the decoy effect, a powerful technique that demonstrates how easily and predictably consumer preferences can be shaped by the architecture of the choice presented to them.

Section 2: Mastering Asymmetric Dominance: A Deep Dive into the Decoy Effect

2.1 The Mechanics of the Nudge: Deconstructing the Decoy

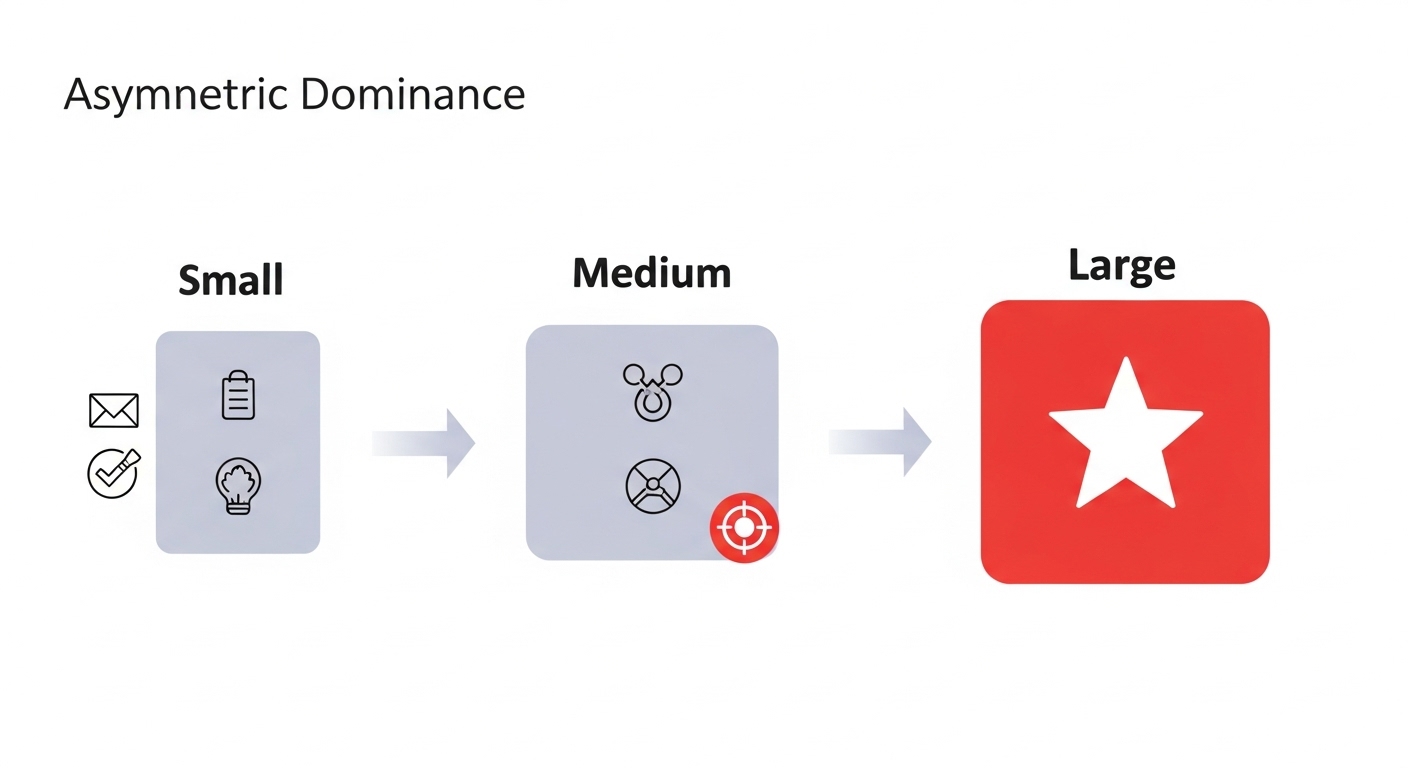

The decoy effect, also known as the attraction effect or the asymmetric dominance effect, is a cognitive bias wherein the introduction of a third, strategically inferior option causes a significant shift in preference between two original options. It is a powerful form of behavioral nudge that can steer consumers toward a more profitable choice while giving them the feeling that they are making a perfectly rational decision. The effect was first identified and described in the early 1980s by researchers Joel Huber, John Payne, and Christopher Puto, whose findings challenged the classical economic principle that a new, irrelevant alternative should not affect choices between existing options.

The strategy is engineered around three distinct components that form the choice set presented to the consumer:

- The Target: This is the option that the business wants the consumer to select. It is typically the higher-margin or more profitable choice.

- The Competitor: This is the original alternative to the target. In a simple two-option scenario, the consumer’s choice between the target and the competitor might be split or lean toward the competitor (e.g., the cheaper option).

- The Decoy: This is the third option, introduced specifically to be “asymmetrically dominated.” This means the decoy is designed to be clearly and unambiguously inferior to the target on all key attributes (e.g., price and quality/quantity). However, it is only partially inferior to the competitor; it may be better on one attribute but much worse on another.

The decoy is not intended to be chosen. Its sole purpose is to alter the choice context, making the target appear overwhelmingly superior by comparison. By providing a simple, direct point of comparison that highlights the target’s strengths, the decoy makes the target the seemingly logical and “smart” choice.

2.2 The Cognitive Science Behind the Choice

The decoy effect’s remarkable power stems from its ability to exploit several fundamental psychological principles that govern human decision-making. It works because it provides a cognitive shortcut that alleviates the stress of difficult choices and offers a clear path to a defensible decision.

- Simplifying Cognitive Load: When faced with multiple options, consumers can experience “choice overload,” a state of anxiety and indecisiveness that can hinder purchasing. The decoy effect simplifies this complex cognitive task. By being clearly inferior to the target, the decoy provides an easy way to eliminate one option, making the decision feel more manageable. It reduces a difficult trade-off (e.g., between price and quality) to a simple judgment of dominance, which is cognitively much easier to process.

- The Contrast Effect: The human brain evaluates options by comparing them. The decoy is engineered to create a stark and favorable contrast for the target option. Consider a classic example: a small popcorn for $3 and a large for $7. The choice is a trade-off between price and quantity. By introducing a medium popcorn (the decoy) for $6.50, the contrast shifts dramatically. The large popcorn is now only 50 cents more than the medium, making it seem like an incredible value, whereas the medium seems like a terrible deal. The decoy makes the target’s attributes appear far more attractive than they did in its absence.

- Loss Aversion Framing: The decoy can subtly frame the choice in terms of loss aversion.

By making the decoy clearly inferior in value to the target, choosing any option other than the target can be perceived as accepting a loss. The decoy highlights what the consumer stands to lose in value by not selecting the target, making the target option feel like the “safe” choice to avoid a bad deal.

- Choice Justification: Perhaps the most profound psychological mechanism at play is the need for justification. Humans do not just want to make a choice; they want to feel that their choice is rational and defensible. The decoy provides a simple, ready-made rationale for selecting the target. A consumer can easily explain, to themselves or others, “I chose the large popcorn because it was only 50 cents more than the medium for a lot more popcorn.” This justification is a powerful driver of behavior; research has shown the decoy effect is even stronger when participants know they will have to explain their decision afterward. This moves the decoy effect beyond a simple pricing trick; it is a justification engine that increases a consumer’s confidence and satisfaction with their decision, reducing the likelihood of post-purchase regret.

2.3 Case Studies in Asymmetric Dominance

The decoy effect is not a theoretical curiosity; it is a widely deployed strategy visible across numerous industries. Analyzing these real-world applications reveals the underlying architecture of the tactic.

- The Economist Subscription Model: This seminal case study, popularized by behavioral economist Dan Ariely, provides a clear illustration of the effect. When students were offered two subscription options—an online-only subscription for $59 and a print-and-web subscription for $125—most chose the cheaper online option. However, when a third option was introduced—a print-only subscription for $125 (the decoy)—the results flipped dramatically. With the decoy present, 84% chose the print-and-web option. The print-only decoy was clearly inferior to the print-and-web bundle at the same price, making the bundle seem like an exceptional deal and the only logical choice.

- Cinema Popcorn Pricing: This is a classic example of manipulating quantity and price. A cinema might offer a small popcorn for $3 (the competitor) and a large for $7 (the target). To steer customers toward the large, they introduce a medium popcorn for $6.50 (the decoy). The medium is asymmetrically dominated by the large—it offers less popcorn for only a marginal price difference. No one is expected to buy the medium; its presence makes the large seem like an undeniable bargain.

- Starbucks Sizing: The coffee giant’s sizing structure—Tall (small), Grande (medium), and Venti (large)—often employs the Grande as a decoy. For example, if a Tall is $3, a Grande is $4.50, and a Venti is $5, the price jump from Tall to Grande is significant ($1.50). However, the jump from Grande to Venti is only 50 cents. This positions the Venti as a much better value proposition relative to the Grande, nudging customers who might have otherwise settled for the medium to upgrade to the large, more profitable size.

- Apple’s Product Tiers: Technology companies frequently use the decoy effect in their product lineups. When launching a new iPhone, Apple might offer three storage options: 128 GB, 256 GB (the target), and 512 GB. The price difference between 128 GB and 256 GB might be $100, while the difference between 256 GB and 512 GB is also $100. For many users, the jump to 512 GB feels excessive, making it a form of decoy that positions the 256 GB model as the “sweet spot” with the best balance of price and features. In other cases, an ultra-high-end model can serve as a decoy to make the next model down seem more reasonably priced.

- SaaS and Streaming Subscriptions (Netflix): Subscription services often present tiered pricing plans that leverage the decoy effect. Netflix might offer a Basic, Standard, and Premium plan. The Premium plan, with features like 4K streaming and more simultaneous screens for a higher price, can act as a decoy. Its purpose is not necessarily to be the most popular choice, but to make the Standard plan—the one Netflix aims to sell most—appear to be the best value for the average user, providing a clear upgrade from Basic without the high cost of Premium.

The following table provides a structured breakdown of these classic examples, illustrating the consistent application of the target, competitor, and decoy framework.

| Case Study | Competitor (Option A) | Target (Option B) | Decoy (Option C) | Psychological Nudge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Economist | Web-Only: $59 | Print + Web: $125 | Print-Only: $125 | The decoy is the same price as the target but offers far less value, making the target seem like a free upgrade. |

| Cinema Popcorn | Small: $3 | Large: $7 | Medium: $6.50 | The decoy is priced very close to the target but offers significantly less quantity, making the target’s value proposition irresistible. |

| Starbucks Coffee | Tall (12 oz): $3 | Venti (20 oz): $5 | Grande (16 oz): $4.50 | The price per ounce for the target is much better than for the decoy, encouraging a small incremental spend for a large gain in quantity. |

| Apple iPhone | 128 GB Model: $799 | 256 GB Model: $899 | 512 GB Model: $1099 | The highest-priced model serves as a decoy anchor, making the mid-tier target seem like the most reasonable and balanced choice. |

| Netflix Subscription | Basic Plan: $9.99 | Standard Plan: $15.49 | Premium Plan: $19.99 | The decoy (Premium) offers features many users don’t need at a high price, framing the target (Standard) as the best value for money. |

2.4 Strategic Implementation and Pitfalls

While the decoy effect is a powerful tool, its successful implementation requires careful design and an awareness of potential risks. Careless application can not only be ineffective but can also damage consumer trust.

Best Practices for Implementation:

- Limit the Options: The decoy effect is most potent when the choice set is simple. The classic and most effective structure involves three options: the target, the competitor, and the decoy. Adding more choices can introduce complexity, trigger choice paralysis, and dilute the effect’s power.

- Design an Effective Decoy: The decoy must be carefully calibrated. It should be similar enough to the target to invite direct comparison but be clearly inferior in terms of value (e.g., price-to-feature ratio). It should feel like a real choice, even if it is rarely selected.

- Strategic Placement: The decoy should be positioned physically or visually next to the target to facilitate the comparison that drives the effect.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid:

- The Obvious Decoy: If the decoy is so unattractive or nonsensical that consumers immediately recognize it as a manipulative tactic, the strategy can backfire. This can erode trust and lead to a negative perception of the brand. The decoy must be inferior, but not absurd.

- Overuse and Customer Dissatisfaction: Repeated or clumsy use of decoy pricing can lead customers to feel manipulated, especially if they later realize they were nudged into a more expensive purchase than they needed. The target option should still represent genuine value for the customer segment it is aimed at.

- Contextual Dependence: The effectiveness of the decoy effect is not universal. It can vary based on the product category, cultural context, and the consumer’s level of expertise or sophistication. What works for a low-stakes purchase like popcorn may be less effective for a complex, high-stakes decision.

Section 3: The Power of the Package: A Strategic Guide to Product Bundling

3.1 The Psychology of the Bundle: Why We Love a Package Deal

Product bundling is a marketing strategy in which a company groups two or more products or services together and sells them as a single combined unit, often for a lower price than if the items were purchased separately. While the economic incentive of a discount is a primary driver, the enduring success of bundling lies in its deep-seated psychological appeal, which taps into several cognitive shortcuts that simplify and enhance the consumer’s purchasing experience.

- Simplification and Reduced Cognitive Load: In a marketplace saturated with options, consumers often face the “paradox of choice,” where an excess of alternatives leads to decision fatigue and anxiety. Bundling acts as a powerful antidote. By pre-selecting complementary items—such as a camera, lens, and memory card—businesses reduce the cognitive load on the consumer. This simplifies the decision-making process, eliminates the need for extensive research on compatibility, and provides a frictionless path to a complete solution, leading to faster and easier purchases.

- Perceived Value and Savings: The most explicit appeal of bundling is the perception of getting more for less. When a bundle is priced lower than the sum of its individual components, it triggers a powerful sense of reward and makes the consumer feel they have secured a “smart deal”. This perception of value is a key driver of purchasing decisions and can be enhanced by clearly communicating the savings, for example, by showing the original combined price struck through next to the new bundle price.

- Reduced “Pain of Paying”: Behavioral economics research has identified the “pain of paying”—the negative emotion experienced when parting with money. Bundling can effectively mitigate this pain.

By combining multiple items into a single price point, it becomes more difficult for consumers to evaluate the exact cost and “right” price for each individual component. This obfuscation of individual prices makes the overall transaction feel less like a series of small, painful expenses and more like a single, value-oriented purchase.

-

The Illusion of Abundance: Bundles can create an illusion of value through sheer volume, even if the consumer does not need or use every component. A cable television package with over 200 channels, for example, feels more valuable than a 50-channel package, even though the average viewer may only watch a small fraction of them. This sense of abundance can make the bundle feel like a better and more comprehensive option, justifying the expense.

3.2 The Presenter’s Paradox: When Bundling Backfires

Despite its psychological advantages, bundling is not without its risks. A critical nuance that strategists must understand is the “presenter’s paradox,” a phenomenon where adding a less desirable or inexpensive item to a bundle can paradoxically decrease the perceived value of the entire package.

Research has shown that when consumers evaluate a bundle, they don’t always sum the values of the individual items; instead, they often engage in “categorical thinking” or “value averaging.” This mental shortcut means that a highly desirable, expensive product (e.g., a $2,299 home gym) can be devalued when bundled with a cheap, low-value item (e.g., a free fitness DVD). The presence of the inexpensive item can dilute the premium perception of the main product, causing consumers to be willing to pay less for the bundle than for the high-end product alone.

This phenomenon, termed “negative bundling,” occurs when the included items are perceived as irrelevant, mismatched, or so cheap that they cheapen the overall brand image. For example, bundling a luxury handbag with a cheap plastic keychain could damage the perceived exclusivity of the handbag. To be effective, every item in a bundle must be perceived as adding genuine, relevant value. The strategic balancing act is to offer a package that feels like a cohesive, value-additive solution, ensuring that the consumer’s focus remains on the overall benefit rather than on the diminished value of a minor component.

3.3 A Taxonomy of Bundling Strategies

Bundling is not a monolithic strategy; it encompasses a variety of models that can be adapted to different business goals, from clearing inventory to introducing new products. Understanding this taxonomy is essential for designing effective bundling programs.

-

Pure Bundling: In this model, the products are available only as a bundle and cannot be purchased individually. This strategy is common when the components have a high degree of complementarity or when the business model relies on selling a complete ecosystem. Examples include Microsoft Office Suite (where individual apps like Word and Excel are primarily sold as part of the 365 subscription) and traditional cable television packages.

-

Mixed Bundling: This is a more flexible approach where consumers have the choice to either buy the bundle or purchase the individual components separately. This model is widely used in the fast-food industry, where a customer can buy a burger, fries, and a drink individually or as a discounted “Value Meal”. Mixed bundling caters to a broader range of preferences and gives customers a sense of control while still nudging them toward the better-value bundle.

-

Mix-and-Match (“Build Your Own”) Bundling: This strategy empowers customers to create their own personalized bundle from a predefined list of options, often for a fixed price or a tiered discount. Examples include “build your own snack box” services or apparel promotions like “choose any 3 T-shirts for $50”. This approach enhances customer satisfaction by providing a sense of control and personalization, and it can yield valuable data on which product combinations are most popular.

-

Cross-Sell Bundling: This involves grouping complementary products that fall into different categories or may even be from different vendors. Amazon’s “Frequently Bought Together” feature is a prime example of data-driven cross-sell bundling, suggesting items like a camera, a tripod, and a memory card based on the purchasing patterns of other customers. This strategy is highly effective at increasing the average order value by anticipating customer needs.

-

New Product Bundling: To encourage trial and accelerate the adoption of a new product, businesses can bundle it with a popular, established bestseller. A new video game console, for example, is often launched in a bundle with a highly anticipated game or popular accessories. This reduces the perceived risk for the customer and leverages the popularity of the existing product to generate momentum for the new one.

-

Inventory Clearance Bundling: Bundling provides an effective mechanism for managing inventory by pairing slow-moving or excess stock with high-demand products. This helps clear out old inventory that might otherwise become a depreciating asset, making space for new products and recouping costs on items that are difficult to sell on their own.

3.4 Case Studies in Value Creation

The application of bundling strategies is ubiquitous across modern commerce, demonstrating its versatility and effectiveness in driving business objectives.

-

Food & Beverage: McDonald’s Value Meals are a quintessential example of mixed bundling, simplifying the ordering process and offering clear value to customers. Starbucks employs seasonal bundling, pairing a new holiday drink with a festive pastry to encourage impulse purchases and create a sense of timely appeal.

-

Technology & Software: The Microsoft Office Suite and Adobe Creative Cloud are classic examples of pure bundling, where a comprehensive set of powerful tools is offered as a single subscription, making it the industry standard for professionals. Dell and other hardware manufacturers use add-on bundling, packaging a laptop with essential accessories like a mouse and carrying case to provide a complete, convenient solution for the customer.

-

Entertainment: The entertainment industry thrives on bundling. Streaming services like Netflix and Spotify often partner with telecommunication companies to bundle their subscriptions with internet or mobile plans, increasing customer retention for both parties. Sony’s PlayStation and Microsoft’s Xbox have long used new product bundling, launching consoles with popular games to create an attractive, all-in-one entry point for gamers.

-

Travel & Services: Online travel agencies like Expedia are masters of mixed and build-your-own bundling, allowing travelers to combine flights, hotels, and car rentals into a customized vacation package for a discounted price. The insurance industry uses pure bundling to sell auto, home, and life insurance policies together, offering convenience and significant cost savings to create long-term customer relationships.

-

Retail & Apparel: Beauty retailers like Sephora curate themed bundles or “beauty kits” that group complementary skincare or makeup products, introducing customers to new items and encouraging a more comprehensive brand experience. Home improvement stores like Home Depot offer DIY kits (e.g., a complete painting set with brushes, rollers, and trays), positioning themselves as solution providers that simplify projects for their customers.

3.5 Designing High-Performance Bundles

Creating a successful bundle is more art than science, requiring a strategic approach that balances customer value with business objectives. An effective framework for designing high-performance bundles includes several key components.

-

Data-Driven Product Selection: The most effective bundles are not random assortments but are thoughtfully curated based on customer data. Businesses should analyze purchasing patterns to identify products that are frequently bought together or that logically complement one another. A bundle should “make sense” to the customer and solve a genuine need or problem. Bundling unrelated items can confuse customers and reduce the perceived value of the offer.

-

Strategic Pricing and Discounting: The bundle must offer a clear and compelling value proposition, which typically involves a discount compared to the sum of the individual items’ prices. However, the discount should be carefully calculated to ensure it is attractive enough to drive sales without excessively eroding profit margins. The goal is to increase the total average order value, so the profitability of the overall transaction must be maintained.

-

Clear Value Communication: It is not enough for a bundle to offer good value; that value must be communicated explicitly to the customer. Marketing materials should clearly state the benefits of the bundle, how the products complement each other, and, most importantly, the exact savings the customer receives by purchasing the package. Visual cues, such as showing the higher, non-bundled price crossed out, can be particularly effective at highlighting the value of the deal.

An Integrated Toolkit for Psychological Pricing

Effective pricing strategy is rarely about the application of a single tactic in isolation. The most sophisticated approaches construct a multi-layered “choice architecture,” where different psychological levers work in concert to guide consumer behavior. Understanding how the decoy effect and product bundling fit within this broader toolkit—and how they interact with other techniques—is essential for developing a truly strategic pricing model.

4.1 Comparative Analysis: Decoy Effect vs.

Product Bundling

While both the decoy effect and product bundling are powerful tools that leverage cognitive biases to influence purchasing decisions, they operate through distinct mechanisms and are often suited to different strategic goals.

The decoy effect is fundamentally a strategy of context manipulation. It does not create a new product; rather, it introduces a new point of comparison to alter the perceived value of existing options. Its primary function is to simplify a trade-off decision (e.g., price vs. quantity) and make one option—the target—appear dominant and logically superior. It is a scalpel, used to precisely steer a choice between two well-defined alternatives.

In contrast, product bundling is a strategy of value creation and simplification. It combines multiple products to create a new, single offering or SKU. Its psychological power comes from reducing cognitive load, creating a perception of savings, and providing a convenient, all-in-one solution. It is a tool for increasing the average order value and introducing customers to a wider range of a company’s products.

These two strategies can also be used synergistically. A business could, for example, offer three distinct product bundles, where one is intentionally designed as a decoy to make another, more profitable bundle the clear target. Imagine a software company offering a “Basic Bundle,” a “Pro Bundle” (the target), and a “Standard Bundle” (the decoy). The Standard Bundle might be priced very close to the Pro Bundle but lack one or two critical features, making the small price increase for the Pro Bundle seem like an obvious and valuable upgrade. In this way, the principles of asymmetric dominance are applied not to individual products, but to entire packages.

4.2 Essential Complements in the Pricing Strategist’s Toolkit

To build a robust choice architecture, the decoy effect and bundling should be integrated with other foundational psychological pricing techniques.

Price Anchoring

As previously discussed, anchoring is the practice of establishing a reference point to influence subsequent judgments. It is a natural partner to both the decoy effect and bundling. A high-priced, ultra-premium product can serve as an anchor that makes all other options, including the target, seem more reasonably priced. Similarly, when presenting a bundle, showing the total price of the items if purchased separately ($150) before revealing the bundle price ($99) anchors the consumer’s perception of value on the higher number, making the savings feel more substantial.

Charm Pricing (The Left-Digit Effect)

This is one of the most pervasive and well-documented pricing tactics. It involves setting prices just below a round number, such as $9.99, $19.95, or $49. The strategy works because of the “left-digit bias”: consumers process numbers from left to right, and their perception of the price is anchored on the first digit they see. Thus, $19.99 is psychologically encoded as being in the “ten-dollar range” rather than the “twenty-dollar range,” making it feel significantly cheaper than $20.00, despite the one-cent difference. This tactic is most effective for products where a “value” perception is desired.

Prestige Pricing

This strategy operates at the opposite end of the spectrum from charm pricing. It involves setting high, often rounded, prices (e.g., $500, $10,000) to signal luxury, exclusivity, and superior quality. For certain consumer segments, a high price is not a deterrent but an attraction, as it serves as a heuristic for quality and status. Luxury brands like Rolex and Louis Vuitton meticulously avoid charm pricing because it would undermine their premium positioning by signaling “discount” or “bargain”.

Price Framing

The presentation of a price can be as important as the price itself. Price framing is the art of contextualizing a price to make it seem more palatable or attractive. For example, a high annual cost can be reframed into a small daily or monthly equivalent: a $1,825 annual subscription feels daunting, but framing it as “just $5 a day” makes it seem far more manageable. Similarly, a promotion can be framed in different ways to maximize its psychological impact. Research shows that for low-priced items, a percentage discount (“50% off”) is often perceived as more significant, while for high-priced items, an absolute dollar amount (“$500 off”) can feel more substantial. The classic “Buy One, Get One Free” is another powerful frame that often proves more appealing than the mathematically equivalent “50% off two items,” as it taps into the zero-price effect, our irrational love for getting something for “free”.

The most effective pricing pages and marketing campaigns do not rely on a single one of these tactics. Instead, they integrate them into a cohesive system. A modern SaaS pricing page is a masterclass in this integrated approach. It might feature three tiers (leveraging the decoy effect), with prices ending in .99 (charm pricing), an option to pay annually to “save 20%” (price framing and loss aversion), and a highlighted “Most Popular” plan (social proof). This is not a collection of disparate tricks but a carefully designed choice architecture where every element works in concert to guide the consumer toward a specific outcome while making them feel confident and intelligent in their decision.

Strategic Implementation, Market Positioning, and Ethical Guardrails

5.1 Pricing for Market Position: Signaling Value to the World

Psychological pricing strategies are not merely short-term sales tactics; their consistent application becomes a core component of a brand’s identity and market positioning. The pricing choices a company makes send powerful signals to consumers about its values, its target audience, and the quality of its products. A coherent pricing strategy reinforces the brand narrative, while an inconsistent one can create confusion and undermine credibility.

Value Brands

Companies competing on price and accessibility, such as Walmart or fast-fashion retailers, consistently employ tactics that signal affordability. Their heavy reliance on charm pricing (prices ending in .97 or .99), prominent “rollback” or “sale” signs (high-low pricing and anchoring), and frequent “Buy One, Get One” (BOGO) offers all reinforce a brand promise centered on saving the customer money. Their use of bundling is typically focused on volume discounts (e.g., multi-packs of household goods).

Premium and Luxury Brands

At the other end of the market, luxury brands like Tiffany & Co. or Tesla use pricing to signal exclusivity, superior quality, and status. They deliberately use prestige pricing, setting high, rounded numbers (e.g., $5,000 for a piece of jewelry) that convey a sense of simplicity, transparency, and quality. They actively avoid charm pricing, as the “.99” ending is psychologically associated with discounts and bargains, which would dilute their premium image. Their bundling strategies, if used, focus on value-adds and enhanced experiences rather than discounts, such as a premium support package or exclusive accessories.

Convenience-Oriented Brands

Brands that position themselves as solution-providers often build their strategy around product bundling. Meal-kit services like HelloFresh, for example, don’t compete on being the cheapest way to eat; they sell the convenience of a curated, all-in-one solution that saves customers time and mental effort. Similarly, travel companies like Expedia bundle flights, hotels, and car rentals to position themselves as a one-stop shop for frictionless travel planning. For these brands, the bundle is the product, and its value is communicated in terms of convenience and simplicity, not just cost savings.

5.2 The Ethics of Influence: Drawing the Line at Manipulation

The power of psychological pricing comes with significant ethical responsibilities. These techniques are designed to leverage cognitive biases, and there is a fine line between ethically guiding a consumer’s choice and unethically manipulating it. The failure to navigate this distinction can lead to consumer backlash, loss of trust, and long-term damage to a brand’s reputation.

Key Ethical Concerns:

- Manipulation of Autonomy: At its most aggressive, psychological pricing can undermine a consumer’s ability to make an autonomous choice that serves their best interests, instead nudging them toward a decision that primarily benefits the seller.

- Lack of Transparency: Businesses rarely, if ever, disclose that they are using a decoy or other psychological tactics. This lack of transparency can be perceived as a form of deception, especially if a consumer later feels they were tricked into overspending.

- Exploitation of Biases: These strategies work by taking advantage of inherent weaknesses in human cognition. A critical ethical debate centers on whether it is fair to exploit these predictable irrationalities for commercial gain.

- Impact on Vulnerable Consumers: Certain populations, such as those with limited financial literacy or cognitive impairments, may be more susceptible to these tactics, raising questions about consumer protection.

Establishing Ethical Guardrails:

- The key to deploying these strategies ethically lies in a commitment to transparency and genuine value alignment. The goal should be to use choice architecture to help a customer easily identify and select the option that genuinely provides the best solution for their needs, not to deceive them into a purchase that will lead to buyer’s remorse.

- An ethical application of the decoy effect, for instance, would guide a customer toward a mid-tier product that offers significantly more value and features than a basic model, representing the best choice for the majority of users.

An unethical application would use a decoy to push a customer toward an overpriced product with marginal benefits. Ultimately, if customers discover the “scheme” and feel they have been manipulated, the short-term revenue gain will be dwarfed by the long-term loss of trust.

A Data-Driven Approach: A/B Testing and Optimization

Implementing psychological pricing should never be based on intuition alone. What works for one audience or product may not work for another. A rigorous, data-driven methodology is essential for optimizing these strategies and ensuring they achieve the desired outcomes without alienating customers.

- A/B Testing: Before rolling out a new pricing structure across the board, businesses should use A/B testing (or split-testing) to compare different versions on small, controlled segments of their audience. One group might see a pricing page with a decoy, while another sees a page without it. This allows the company to measure the real-world impact on key metrics and validate that the strategy is working as intended. Different bundle configurations, discount levels, and price points can all be tested to find the optimal combination.

- Audience Segmentation: Consumers are not a monolith. Different segments will respond to pricing tactics in different ways based on their demographics, purchasing history, and price sensitivity. A data-driven approach allows businesses to segment their audience and tailor pricing strategies accordingly. A price-sensitive segment might respond well to charm pricing and discount bundles, while a quality-focused segment might be more receptive to prestige pricing.

- Monitoring Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): The success of a pricing strategy should be measured holistically. While conversion rate is a critical metric, it is also important to track the average order value (AOV) to see if the strategy is successfully encouraging larger purchases. Furthermore, monitoring customer satisfaction scores, refund rates, and customer lifetime value can provide crucial insight into whether the pricing strategy is building long-term, positive relationships or creating short-term gains at the expense of customer loyalty.

Conclusion: Pricing as a Strategic Narrative

Psychological pricing, when understood and applied with sophistication, transcends the simple act of putting a number on a product. It is the art and science of crafting a strategic narrative of value. Techniques like the decoy effect and product bundling are not just tools for increasing revenue; they are methods for simplifying complex decisions, building consumer confidence, and shaping the perception of a brand in the marketplace.

The immediate goal of these tactics may be to increase the value of a single transaction—to sell the large popcorn instead of the small, or the premium bundle instead of the basic one. However, the consistent warnings about the risk of eroding consumer trust reveal a deeper strategic tension. This tension forces a high-level choice: a business can use these tactics aggressively to extract maximum profit from every sale, risking long-term brand damage. Alternatively, it can use these same principles to guide customers toward the option that genuinely offers them the best value, thereby increasing their satisfaction and confidence.

The most advanced application of pricing psychology, therefore, is not about optimizing for a single transaction but about building long-term relational equity. It involves architecting a choice that leaves the customer feeling empowered, intelligent, and satisfied with their decision. When used in this manner—ethically, transparently, and in true service of the customer’s needs—pricing strategy is transformed from a tool of extraction into a powerful and sustainable engine of relationship-building, creating a competitive advantage rooted not just in cognitive bias, but in enduring customer trust.