Reusable Website Components: Layouts, Includes & Partials

Introduction: The Principle of Component-Based Architecture in Web Development

At the heart of modern software development lies a simple yet profound principle: “Don’t Repeat Yourself,” or DRY. Formulated by Andy Hunt and Dave Thomas, the DRY principle states that “Every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system”. This concept is not merely about avoiding the copy-pasting of code; it is a philosophy aimed at reducing the repetition of any piece of information that is likely to change, thereby making systems easier to maintain and evolve. When a single element of a system is modified, a successful application of DRY ensures that no changes are required in other logically unrelated elements.

The antithesis of this principle is often referred to as WET, an acronym for “Write Everything Twice” or “We Enjoy Typing”. A WET approach, where elements like a website’s navigation bar are duplicated across every single HTML file, creates a significant maintenance burden. A simple update, such as adding a new link, becomes a tedious and error-prone task of finding and replacing every instance across the entire project. This inefficiency is precisely the problem that modern templating systems, particularly within Static Site Generators (SSGs), are designed to solve.

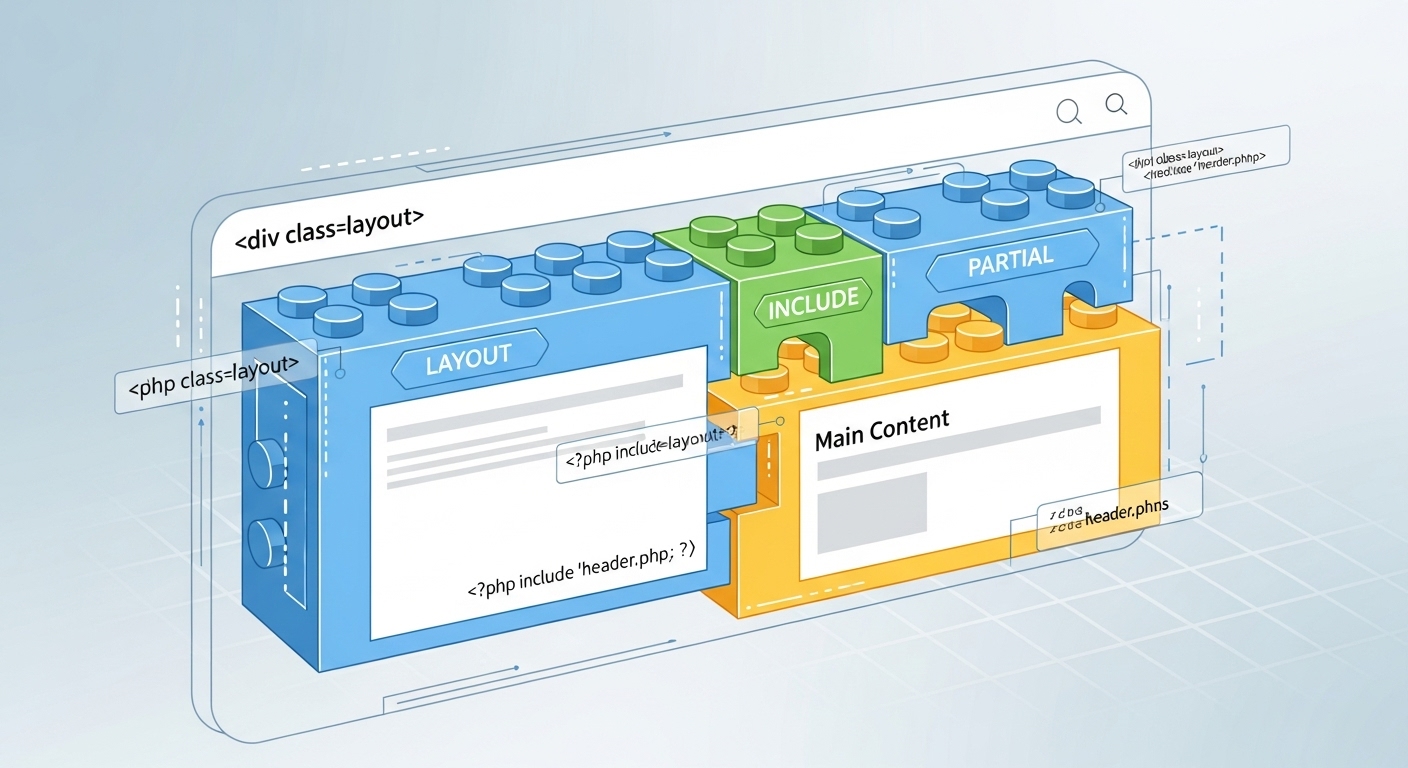

Layouts, includes, and partials are the primary architectural tools that SSGs provide to implement the DRY principle. They facilitate a paradigm shift away from managing individual, monolithic HTML files and toward composing web pages from smaller, manageable, and reusable components. While early web development tools like Dreamweaver attempted to solve this with proprietary features, and server-side technologies like PHP offered include statements, SSGs bring this component-based power to the build process itself. They compile templates and content into purely static HTML files that are exceptionally fast, secure, and simple to deploy. Understanding these templating concepts is therefore fundamental to leveraging the full power of SSGs and building scalable, maintainable websites.

Section 1: Deconstructing the Template: Core Concepts Defined

1.1 Layouts: The Architectural Blueprint

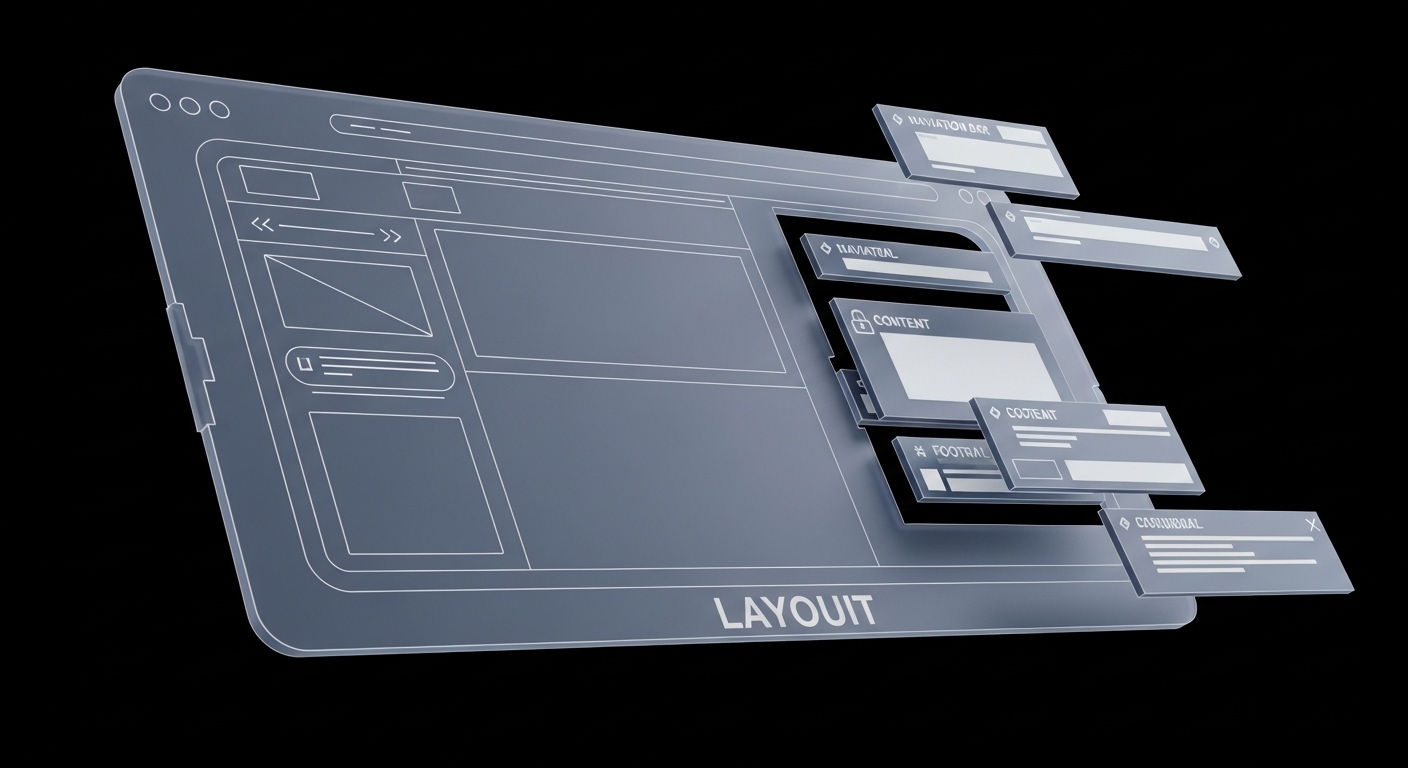

A layout is the highest-level structural template in an SSG’s templating hierarchy. It serves as the architectural blueprint, “frame,” or “shell” for a webpage. A layout typically contains the overarching HTML structure that remains consistent across many pages of a site, such as the <!DOCTYPE> declaration, the <html>, <head>, and <body> tags.

The defining feature of a layout is that it contains one or more placeholders where page-specific content is injected during the site generation process. This is commonly achieved with a special variable, such as {{ content }} in Jekyll and Eleventy, or a content block like {{ block “main”. }} in Hugo. Individual content files, such as a Markdown page for an “About Us” section, declare which layout to use within their “front matter“—a small block of metadata at the top of the file. For example, adding layout: default to a page’s front matter instructs the SSG to wrap that page’s rendered content within the default layout file. This establishes a clear relationship where the content file “fills in the blanks” defined by the layout. Conventionally, these layout files are stored in a dedicated directory, such as _layouts in Jekyll or within the _includes folder in Eleventy.

1.2 Partials & Includes: The Reusable Building Blocks

Partials, often called includes, are smaller, self-contained snippets of HTML designed to be reused in multiple places, such as within different layouts or even on different pages. While the terminology varies between generators—Jekyll and Eleventy favor the term “include” and the {% include %} tag, whereas Hugo standardizes on “partial” and the {{ partial }} function—their purpose is identical: to encapsulate a reusable piece of the user interface.

Classic examples of components perfectly suited for partials include website headers, navigation bars, footers, sidebars, author bio cards, social media sharing buttons, and contact forms. The primary benefits of using partials are twofold. First, they dramatically improve project organization by breaking down large, complex template files into smaller, more focused, and manageable pieces. Second, and more critically, they enhance maintainability by creating a single source of truth for repeated UI elements. When a change is needed—for instance, updating the copyright year in the footer—the developer only needs to edit a single partial file for that change to propagate across the entire website. These files are also stored in a conventional directory, typically _includes for Jekyll and Eleventy, and layouts/partials for Hugo.

1.3 The Symbiotic Relationship: How Layouts and Partials Work Together

Layouts and partials function together in a clear hierarchy to assemble a final HTML page. This process demonstrates a robust separation of concerns, where each file type has a distinct responsibility. The typical build process unfolds as follows:

- The SSG begins with a content file, such as about.md.

- It reads the front matter of about.md and identifies the specified layout, for example, layout: default.

- The generator then loads the corresponding layout file, _layouts/default.html.

- This layout file contains instructions to include various partials, such as {% include “header.html” %} at the top and {% include “footer.html” %} at the bottom.

- The SSG retrieves the content of header.html and footer.html from the _includes directory and injects them into their respective places within the layout.

- Finally, the SSG renders the Markdown from about.md into HTML and injects this final content into the {{ content }} placeholder within the layout.

This modular assembly line is highly efficient. A common mistake for beginners is to place large, complex chunks of HTML, like a 50-line navigation menu, directly into the layout file. While functional, this approach conflates the responsibilities of structure and component implementation. The layout’s primary role should be to act as an orchestrator—defining the main structural regions of the page and calling upon partials to fill those regions. The partials, in turn, are the implementers, containing the specific markup for each UI component. This architectural distinction between framing (the layout) and filling (the partials and content) is key to building clean, scalable, and easily maintainable websites.

Section 2: Strategic Implementation: When to Use Layouts vs. Partials

Choosing between a layout and a partial becomes straightforward when considering their distinct roles. A simple set of heuristics can guide this architectural decision.

2.1 The Litmus Test: Differentiating Structure from Component

To determine whether a piece of code should be a layout or a partial, developers can ask the following questions:

- Is it a full-page “shell”? Does the file contain the root <html>, <head>, and <body> tags, along with a primary placeholder for page-specific content? If yes, it is a layout.

- Is it a piece of a page? Is it a self-contained UI element, like a navigation bar, a footer, or a product card, that will be placed inside a layout or another template? If yes, it is a partial.

- Does it define where content goes, or what the content is? Layouts are concerned with defining where content will be injected (e.g., via {{ content }}). Partials are concerned with defining what the content is (e.g., the specific HTML for a navigation menu).

The following table provides an at-a-glance summary to aid in this decision-making process.

| Attribute | Layouts | Partials/Includes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Page structure, blueprint, or shell | Reusable UI component or code snippet |

| Scope | Wraps entire page content | A fragment within a page or another layout |

| Analogy | The Picture Frame | The Lego Brick |

| Typical Content | <html>, <head>, <body>, {{ content }} | <nav>, <footer>, <aside>, forms, cards |

| Invocation | Via front matter (layout: page.html) | Via template tag ({% include %} or {{ partial }}) |

| Key Feature | Content injection and inheritance | Encapsulation and reusability |

2.2 Advanced Layout Techniques: Inheritance and Chaining

Layouts can be made even more powerful by inheriting from other layouts, a technique known as layout chaining. This allows for the creation of structural variations without duplicating the common HTML foundation.

The process typically begins with a “base” layout (e.g., _layouts/default.html) that contains the absolute minimum HTML structure required for every page on the site. A more specific layout, such as _layouts/post.html for blog posts, can then extend this base layout by specifying layout: default in its own front matter. This post.html layout can introduce additional structural elements unique to blog posts, like a hero image container or an author byline section, while its own content is ultimately injected into the base layout’s {{ content }} block. This creates a chain: the blog post content fills the post layout, which in turn fills the default layout. This is an extremely effective DRY technique for managing page structure at scale. For example, a home page layout could add a full-width hero section, and a blog post layout could add a sidebar, but both would inherit the same <head>, header, and footer from a single base layout.

2.3 Advanced Partial Techniques: Parameterization and Context

While simple includes are static, their true power is unlocked when they are transformed into dynamic, reusable components by passing data to them.

“`

This evolution from simple code-chunking to a true component-based architecture is a hallmark of modern SSGs.

- In Jekyll, parameters can be passed directly within the include tag. For instance,

{% include note.html content="This is my sample note." %}passes a content variable to the note.html partial, which can then be accessed using{{ include.content }}. This is ideal for creating components like alert boxes or image figures where the structure is constant but the data varies. - In Hugo, passing context is a core concept. The

{{ partial "header.html". }}syntax uses a trailing dot (.) to pass the entire page context to the partial. This gives the partial access to all page variables, such as.Titleand any custom parameters defined in the front matter. Custom data can also be passed using adictfunction, such as{{ partial "header.html" (dict "color" "blue") }}. - In Eleventy, partials included with the

{% include %}tag automatically have access to the including page’s front matter data. For more complex components that require explicitly scoped parameters, templating languages like Nunjucks offer macros. For components that need to wrap a block of content, Eleventy’s paired shortcodes are the most powerful and appropriate tool.

This ability to pass data to partials mirrors the concept of “props” in modern JavaScript frameworks like React or Vue. The partial becomes analogous to a UI component, and the parameters become its props. This parallel reveals a deep architectural connection, demonstrating how skills in SSG templating are directly transferable to more complex front-end ecosystems.

Section 3: A Tale of Three Generators: A Comparative Analysis

While the core concepts of layouts and partials are shared, their implementation and capabilities differ across popular static site generators.

3.1 Jekyll: The Pioneer’s Approach with Liquid

- Structure: Jekyll establishes a clear and conventional separation of concerns with a

_layoutsdirectory for layouts and an_includesdirectory for partials. - Layouts: It employs a straightforward layout chaining model. A child layout specifies its parent in its front matter, and its content is injected into the parent’s

{{ content }}tag. - Includes: The Liquid templating engine provides the

{% include %}tag. It supports passing named parameters, making it quite capable for creating reusable components. It can also use variables for the filename itself (e.g.,{% include {{ page.my_variable }} %}), allowing for dynamic inclusion based on page data. - Nuance: Jekyll’s system is simple, intuitive, and effective. It set the standard for many SSGs that followed, though it lacks the more sophisticated block-based inheritance found in systems like Hugo.

3.2 Hugo: Performance and the baseof.html Model

- Structure: Hugo uses a powerful but more complex template lookup order. Partials reside in

layouts/partials/, while layouts can exist inlayouts/_default/or in more specific directories that mirror the content structure. - Layouts: The central concept in Hugo’s layout system is the

baseof.htmltemplate. This single file defines the entire page shell using named{{ block }}placeholders (e.g.,{{ block "main". }}and{{ block "title". }}). Other templates, likesingle.html(for single pages) orlist.html(for section pages), do not repeat this shell. Instead, they use{{ define }}blocks to provide the content for the corresponding placeholders in baseof.html. This is a more robust and explicit inheritance model than simple chaining. - Partials: Invoked with

{{ partial "name.html". }}, the trailing dot (.) is crucial for passing the current page context, a frequent point of confusion for newcomers. Hugo partials are extremely powerful for creating data-driven components and also support apartialCachedfunction for significant performance gains on large sites. - Nuance: Hugo’s model is arguably the most architecturally advanced, enforcing a strict separation between the page shell (baseof.html) and the content-specific templates that fill it.

3.3 Eleventy: The Flexible Contender

- Structure: Eleventy is highly flexible and configurable. By default, both layouts and includes are expected in the

_includesdirectory, but this can be easily customized in the.eleventy.jsconfiguration file. For better organization, many developers create separate_layoutsand_partialssubdirectories. - Layouts: Its system is similar to Jekyll’s, using front matter (

layout: base.njk) for layout chaining. A standout feature is its template language independence: a Markdown file can use a Nunjucks layout, which could in turn chain to a Liquid layout, offering unparalleled flexibility. - Partials/Includes: The standard

{% include %}tag is used for simple file inclusion, and the included file automatically inherits the parent template’s data. For parameterized components, Nunjucks macros are often used. For more advanced use cases, such as components that wrap around other content, Eleventy’s native paired shortcodes are the most powerful tool. - Nuance: Eleventy’s primary strength is its flexibility. It does not enforce a single architectural pattern but instead provides a spectrum of tools (includes, macros, shortcodes) to handle varying levels of component complexity. This power requires the developer to make more conscious architectural decisions.

The following table offers a comparative summary of these features.

| Feature | Jekyll (Liquid) | Hugo (Go Templates) | Eleventy (Nunjucks/Liquid) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layout Directory | _layouts/ |

layouts/_default/, etc. |

_includes/ (configurable) |

| Partial Directory | _includes/ |

layouts/partials/ |

_includes/ (configurable) |

| Layout Inheritance | Chaining via front matter | baseof.html with block/define |

Chaining via front matter |

| Partial Invocation | {% include 'file.html' %} |

{{ partial "file.html". }} |

{% include 'file.html' %} |

| Parameter Passing | {% include file.html var='val' %} |

{{ partial "f.html" (dict "k" "v") }} |

Accesses parent data; use macros for scoped params |

| Advanced Reusability | Parameterized includes | partialCached, dict context |

macros, paired shortcodes |

Section 4: Practical Workshop: Building a Universal Header and Footer

This section provides a hands-on, practical guide to creating a universal header and footer, applying the concepts discussed above to Jekyll, Hugo, and Eleventy.

4.1 Establishing the Foundation: The Base Layout

First, create the main layout file that will serve as the structural foundation for all pages.

-

Jekyll: Create

_layouts/default.html<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <title>{{ page.title }} | My Site</title> </head> <body> {% include header.html %} <main> {{ content }} </main&n> {% include footer.html %} </body> </html> -

Hugo: Create

layouts/_default/baseof.html<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> {{- partial "head.html". -}} <body> {{- partial "header.html". -}} <main> {{- block "main". }}{{- end }} </main> {{- partial "footer.html". -}} </body> </html> -

Eleventy: Create

_includes/base.njk<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <title>{{ title }} | My Site</title> </head> <body> {% include "partials/header.html" %} <main> {{ content | safe }} </main> {% include "partials/footer.html" %} </body> </html>

4.2 Encapsulating the Components: Creating Header and Footer Partials

Next, create the individual partial files for the header and footer. This isolates their code for easy maintenance.

Header Partial (with Navigation)

-

Jekyll: Create

_includes/header.html<header> <nav> <a href="/">Home</a> <a href="/about.html">About</a> </nav> </header> -

Hugo: Create

layouts/partials/header.html<header> <nav> <a href="{{.Site.BaseURL }}">Home</a> <a href="{{.Site.BaseURL }}about/">About</a> </nav> </header> -

Eleventy: Create

_includes/partials/header.html<header> <nav> <a href="/">Home</a> <a href="/about/">About</a> </nav> </header>

Footer Partial (with Copyright)

-

Jekyll: Create

_includes/footer.html<footer> <p>© {% now '%Y' %} My Awesome Site. All rights reserved.</p> </footer> -

Hugo: Create

layouts/partials/footer.html<footer> <p>© {{ now.Format "2006" }} {{.Site.Title }}. All rights reserved.</p> </footer> -

Eleventy: Create

_includes/partials/footer.html<footer> <p>© {% year %} My Awesome Site. All rights reserved.</p> </footer>Note: Requires a simple shortcode for

yearin.eleventy.js

4.3 Assembling the Page: Integrating Partials into the Layout

This step has already been completed in Section 4.1.

“`html

The base layout files were created with the include or partial calls already in place, demonstrating how the layout acts as the orchestrator that assembles the final page from its constituent parts.

Cross-Platform Implementation: The Final Code

To create a functional “About” page, you would simply create a content file and specify the layout in its front matter.

-

Jekyll: Create about.md

layout: default title: About Us

About Our Company

This is the about page content. -

Hugo: Create content/about.md

title: "About Us"

About Our Company

This is the about page content.

(Hugo will automatically use layouts/_default/single.html which should define the “main” block for baseof.html) -

Eleventy: Create src/about.md

layout: base.njk title: About Us

About Our Company

This is the about page content.

This workshop demonstrates a complete, working example that applies the principles of layouts and partials to achieve a clean, maintainable, and DRY site structure across three major SSGs.

Conclusion: Beyond Repetition—Building Maintainable and Scalable Web Systems

The concepts of layouts, includes, and partials are far more than simple templating features; they are the tangible implementation of a component-based design philosophy within the static site ecosystem. Mastering these tools is the critical step that elevates a developer from creating simple, static pages to architecting professional, large-scale websites that are efficient to build and a pleasure to maintain. By adhering to the “Don’t Repeat Yourself” principle, these mechanisms allow for the creation of a single source of truth for every piece of knowledge in the system, from a navigation link to a page’s structural blueprint.

The architectural thinking cultivated through the use of SSG templating is a universally applicable and transferable skill. The process of identifying components, managing their scope, and passing data as needed is the same whether one is using Jekyll includes, Hugo partials, or components in a JavaScript framework like React. This underscores the value of these concepts as foundational principles of modern web development.

Ultimately, the goal is not just to be DRY for its own sake, but to build systems where complexity is contained and future changes are manageable. As principles like “Avoid Hasty Abstractions” (AHA) suggest, the true mark of an expert developer is knowing when and how to create these abstractions. Often, the most pragmatic approach is to start with some repetition, and only refactor to a reusable component when a true pattern emerges—a practice sometimes called the “Rule of Three“. By thoughtfully applying layouts and partials, developers can build websites that are not only fast and secure but also robust, scalable, and resilient to the inevitable demands of change.

📚 For more insights, check out our web development strategies.