Nepal Executive: Stability, Inclusivity, & Direct Election Debate

Introduction: A Nation at a Constitutional Crossroads

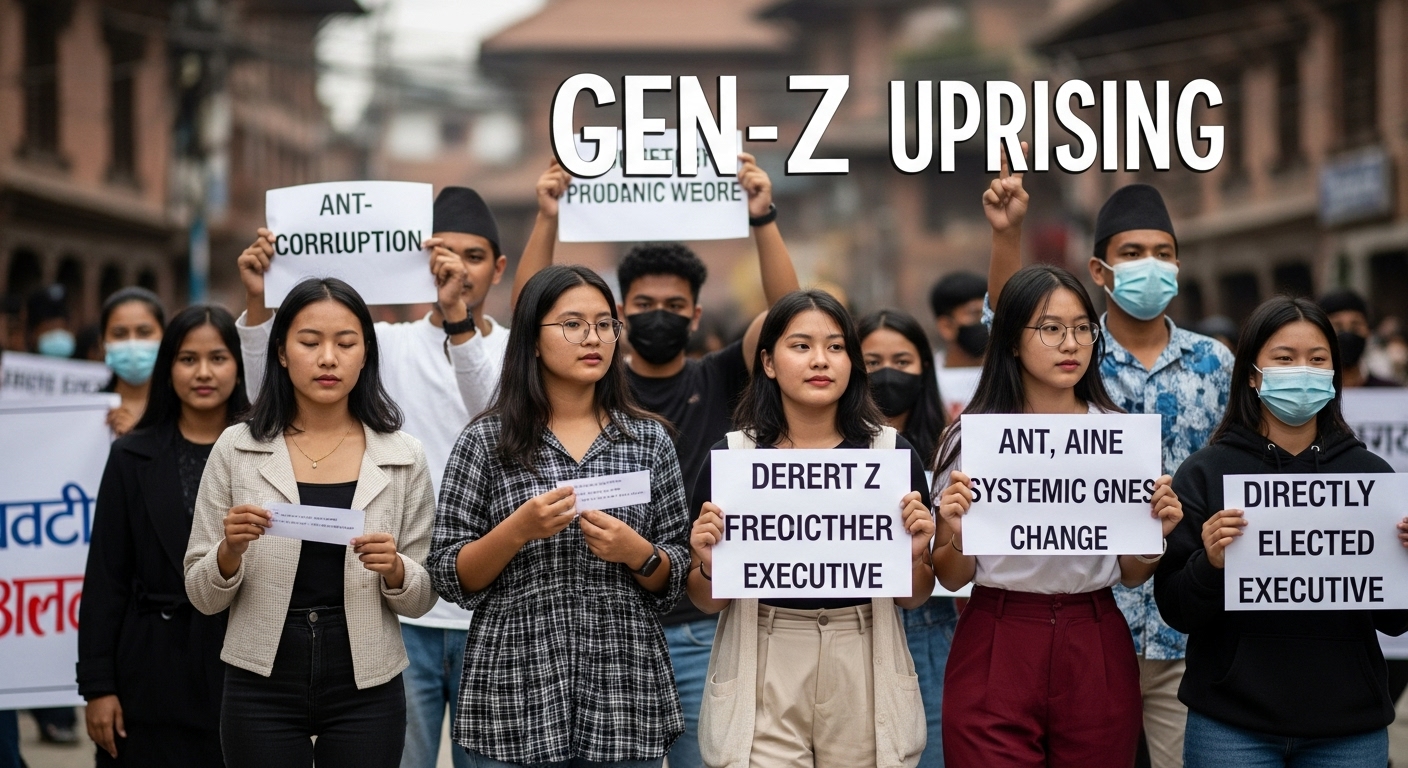

Nepal stands at a pivotal moment in its democratic journey. The recent “Gen Z uprising,” a wave of youth-led protests against endemic corruption, the perpetual dominance of an aging political class, and chronic government inefficiency, has shaken the foundations of the political establishment. This eruption of public discontent is more than a fleeting expression of anger; it has catalyzed a profound national conversation about the fundamental architecture of the state. From the streets of Kathmandu to the highest echelons of power, a powerful demand has emerged for systemic change, with the proposal to replace the current parliamentary system with a directly elected executive at its forefront.

The debate over the form of government is not merely a technical or academic exercise. It strikes at the heart of Nepal’s central political dilemma: the desperate search for political stability and decisive leadership in a nation long plagued by fractious coalition politics, versus the critical imperative to safeguard and deepen a pluralistic democracy in one of the world’s most diverse societies. The allure of a strong, popularly elected leader who can cut through parliamentary gridlock and deliver on long-deferred promises of development is powerful. Yet, this appeal is shadowed by deep-seated fears that such a concentration of power could pave the way for a new form of authoritarianism, unraveling the hard-won gains of inclusivity and representation that are the cornerstones of the 2015 Constitution. The debate, therefore, is a symptom of deeper maladies—a crisis of institutional performance, a breakdown in political culture, and a fraying social contract.

This report argues that while a directly elected executive appears to offer a straightforward solution to Nepal’s chronic political instability, a comprehensive analysis—informed by Nepal’s own turbulent history, the specific nature of its social cleavages, and comparative international experience—reveals profound and potentially irreversible risks. A presidential system in the Nepali context could concentrate power to a dangerous degree, exacerbate ethnic and regional tensions, marginalize minority communities, and create debilitating constitutional gridlock. It contends that sustainable reform lies not in a wholesale constitutional overhaul that risks sacrificing inclusivity for the promise of stability, but in addressing the underlying weaknesses in political culture, institutional integrity, and accountability mechanisms that would plague any system of governance.

To build this case, this report will first establish a conceptual framework defining the different architectures of executive power. It will then delve into the historical legacy of instability that has shaped Nepal’s political crucible. Following this, it will present a balanced examination of the arguments for and against a directly elected executive as they apply specifically to Nepal. The analysis will trace the evolution of this debate within the country’s political discourse, including the shifting stances of major political actors. Crucially, the report will draw lessons from comparative case studies in Sri Lanka, the Philippines, and Indonesia—nations that have grappled with similar challenges of diversity, development, and democratic consolidation under presidential systems. Finally, it will conclude with a synthesis of the findings and a set of strategic recommendations for policymakers, civil society, and the Nepali people as they navigate this critical constitutional crossroads.

I. The Architecture of Executive Power: A Conceptual Framework

The choice of an executive system is one of the most fundamental decisions in constitutional design, shaping the distribution of power, the nature of political accountability, and the overall stability of a government. The debate in Nepal revolves around moving from its current parliamentary model to a presidential one. Understanding the theoretical underpinnings of these systems is essential to evaluating their potential consequences.

Defining the Systems

Political systems are broadly categorized based on the relationship between the executive and legislative branches of government.

- Parliamentary System: This model is defined by a “fusion of powers,” where the executive branch, led by a Prime Minister and a cabinet, originates from and is directly accountable to the legislature (Parliament). The head of government’s democratic legitimacy is derived from their ability to command the confidence of a legislative majority. This confidence can be withdrawn at any time through a “vote of no confidence,” making the executive continuously answerable to the elected representatives of the people. In this system, the roles of head of state (often a ceremonial president or monarch) and head of government are typically separate.

- Presidential System (Directly Elected Executive): In stark contrast, a presidential system is founded on a strict “separation of powers“. The chief executive, the President, is popularly elected by the citizens, either directly or through an electoral college, for a fixed term of office. This direct popular mandate makes the president independent of the legislature. The president typically serves as both the head of state and the head of government, possessing significant executive authority over domestic and foreign policy. The legislature cannot easily remove the president, except through an extraordinary and often difficult impeachment process.

- Semi-Presidential (Hybrid) System: This model combines elements of the previous two, featuring a dual executive structure. A president is directly elected by the people and holds significant executive powers, particularly in areas like foreign policy and defense. Simultaneously, a prime minister, who is accountable to the legislature, serves as the head of government and manages the day-to-day affairs of the state. This system can lead to complex power-sharing arrangements, especially when the president and the parliamentary majority come from different political parties.

Core Analytical Dimensions

The choice between these systems involves navigating inherent trade-offs across several key dimensions of governance.

- Accountability vs. Stability: Parliamentary systems are designed for continuous accountability; a prime minister who loses the support of parliament can be removed quickly, ensuring responsiveness to the legislative will. However, this very feature can lead to chronic instability, especially in multi-party systems where coalitions are fragile and governments can collapse frequently. Presidential systems, with their fixed executive terms, offer a much higher degree of stability and predictability. The trade-off is that accountability is more periodic and less immediate, primarily occurring during scheduled elections, making it difficult to remove an unpopular or ineffective president before their term ends.

- Efficiency vs. Gridlock: In a parliamentary system where the executive commands a majority, the fusion of powers can lead to highly efficient policymaking and legislative action, as the government can confidently pass its agenda. Conversely, the separation of powers in a presidential system, while providing crucial checks and balances, carries a significant risk of legislative-executive gridlock. If the president’s party does not control the legislature (a common scenario known as “divided government”), the two branches can become locked in a stalemate, leading to policy paralysis and an inability to address pressing national issues.

- Representativeness vs. Concentration of Power: Parliamentary systems, particularly when paired with proportional representation electoral rules, tend to produce multi-party legislatures. This often necessitates coalition governments, which can provide representation for a wider array of social, ethnic, and ideological interests within the executive branch. A presidential system, however, is fundamentally a “winner-take-all” contest. It concentrates enormous executive power and national symbolism in a single individual. While this can create a unifying figure, it also risks marginalizing large segments of the population whose candidates lose, potentially alienating minority groups who may feel permanently shut out of the highest office.

The idealized definitions of these governmental systems often fail to capture their real-world performance, especially in nations grappling with post-conflict transitions, deep social divisions, and underdeveloped political institutions. The theoretical promise of parliamentary flexibility can devolve into chronic instability when political parties are fragmented and undisciplined, as has been the case in Nepal. Similarly, the stability offered by a presidential system can transform into a dangerous rigidity, leading to constitutional crisis when an unpopular president clashes with the legislature or when the office is used to enforce the will of a dominant ethnic group, as seen in Sri Lanka. This reveals that the political context—including the prevailing political culture, the strength of the judiciary and civil society, and the nature of social cleavages—is as determinative of outcomes as the constitutional blueprint itself. Therefore, the central task is not simply to compare abstract models, but to rigorously assess their suitability for the unique and challenging political landscape of Nepal.

II. The Nepali Political Crucible: A Legacy of Instability

The contemporary debate over Nepal’s form of government is not an abstract discussion; it is a direct response to a long and painful history of political volatility.

For decades, the nation has been caught in a cycle of aborted democratic experiments, autocratic rule, and violent conflict, creating a deep-seated public yearning for a system that can deliver stability and effective governance.

A History of Aborted Democratic Experiments

Nepal’s modern political history is a chronicle of struggle between autocratic and democratic forces. The century-long rule of hereditary Rana prime ministers, which reduced the monarch to a figurehead, was a period of tightly centralized autocracy. A brief democratic experiment in the 1950s, modeled on the British parliamentary system, culminated in the 1959 elections, which brought the Nepali Congress party to power. This democratic opening was short-lived. In 1960, the king dissolved parliament and banned political parties, instituting the “partyless” Panchayat system, a hierarchical structure of councils that enshrined the absolute power of the monarchy for the next three decades. This history has embedded a dual legacy in the national psyche: a familiarity with and, for some, a nostalgia for centralized, decisive rule, alongside a profound and hard-won aspiration for democratic freedoms.

The 1990 People’s Movement (Jana Andolan) forced the end of the Panchayat system and re-established a multiparty parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarchy. However, the period from 1991 to the early 2000s failed to deliver the promised stability. It was marked by a succession of short-lived, unstable coalition governments, hung parliaments, and intense infighting both between and within the major political parties, primarily the Nepali Congress and the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist) or CPN-UML. This era of political dysfunction, which saw five different governments in as many years during the mid-1990s, coincided with the start and escalation of the Maoist insurgency. This period is frequently cited by critics as definitive proof of the parliamentary system’s unsuitability for Nepal, as it failed to provide the strong, stable governance needed to address the country’s deep-seated socio-economic grievances.

The Post-Conflict Transition and the 2015 Constitution

The decade-long civil war and the subsequent 2006 People’s Movement (Jana Andolan II) led to another seismic political shift: the end of the 238-year-old monarchy and the declaration of Nepal as a federal democratic republic in 2008. This ushered in a protracted and often contentious constitution-making process through two elected Constituent Assemblies. The resulting Constitution of Nepal, promulgated in 2015, was a landmark achievement, representing a political consensus forged in the aftermath of conflict.

The 2015 Constitution establishes a bicameral federal parliament, with the executive power vested in a Prime Minister and their cabinet, who are accountable to the House of Representatives. A key feature of this framework is its mixed electoral system for the 275-member lower house: 165 members are elected through a first-past-the-post (FPTP) system in single-member constituencies, while 110 are elected through a proportional representation (PR) system with the entire country as a single constituency. This mixed system was a deliberate compromise intended to ensure both geographic representation (via FPTP) and the inclusion of Nepal’s diverse ethnic, caste, and gender groups (via PR).

Diagnosing the Pathology of the Current System

Despite the hopes invested in the 2015 Constitution, the post-promulgation era has been characterized by a continuation of the very political pathologies it was meant to cure.

- Chronic Governmental Instability: The pattern of fragile, short-lived governments has persisted. The mixed electoral system, while promoting inclusion, has also led to a fragmented parliament where no single party can easily command a majority. This has institutionalized a culture of unstable coalitions, often held together by opportunistic power-sharing agreements. A particularly glaring example is the arrangement for party leaders to take turns as prime minister for fixed periods, as such as 18 months, until the next election, which reduces the premiership to a rotational post rather than a position of national leadership based on a consistent mandate.

- Systemic Corruption and Patronage: The constant need to form and maintain these fragile coalitions has fueled a political economy of patronage and corruption. The focus of political leaders shifts from policy and governance to the distribution of ministerial portfolios and other state resources to keep coalition partners happy. This dynamic has been observed to have detrimental effects on governance at all levels, fostering an ethical degeneracy where short-term individual or party benefits are prioritized over long-term public welfare. This directly links the structure of parliamentary competition to the systemic corruption that has so enraged the public.

- Erosion of Public Trust: The relentless cycle of instability, coupled with pervasive corruption and the perception that a small, unchanging clique of elderly politicians is simply recycling power among themselves, has led to a profound crisis of legitimacy. Public trust in political parties, parliament, and the democratic process itself has been severely eroded, creating a fertile ground for anti-systemic sentiment.

- Atmosphere of Impunity: Compounding these issues is a persistent failure to ensure accountability for human rights abuses and corruption. The government has taken only limited steps to prosecute officials, including members of the security forces, who have committed abuses, both during the conflict and after. This has created a pervasive “atmosphere of impunity,” reinforcing the public’s belief that the political class is above the law and further alienating citizens from the state.

The interplay of these factors has created a vicious, self-perpetuating cycle. The constitutional design itself, particularly the mixed electoral system intended to foster inclusivity, contributes to parliamentary fragmentation. This fragmentation makes unstable coalition governments a near-inevitability. The political maneuvering required to build and sustain these coalitions normalizes “horse-trading” and patronage, which breeds systemic corruption. This combination of perpetual instability and corruption destroys public faith in the parliamentary system as a whole. This widespread disillusionment, in turn, fuels popular demand for a radical alternative—a strong, directly elected executive who is perceived as being able to transcend the messy, corrupt world of parliamentary politics and impose order. In this way, the very mechanisms designed to make the state more representative inadvertently generate the conditions that lead citizens to clamor for a less representative, more centralized form of rule.

The Promise of a New Order: The Case for a Directly Elected Executive

The growing call for a directly elected executive in Nepal is fueled by a deep-seated frustration with the status quo and a compelling set of arguments that promise a more stable, accountable, and effective form of governance. Proponents see it not as a minor tweak but as a fundamental solution to the chronic ailments of the Nepali state.

The Core Appeal: Political Stability and Decisive Governance

The most powerful argument in favor of a directly elected executive is the promise of political stability. A president or executive prime minister elected for a fixed term—for example, five years—would be insulated from the constant threat of no-confidence motions and the collapse of fragile parliamentary coalitions that have defined Nepali politics for over three decades. In a country that has witnessed 25 prime ministers in 35 years and where power-sharing deals involve leaders rotating the premiership every 18 months, the idea of a government that can serve a full term is deeply appealing. This stability is seen as a prerequisite for effective governance, allowing for the formulation and implementation of long-term development policies and infrastructure projects without the constant disruption caused by changes in government. Advocates argue that only a stable executive can break the cycle of policy paralysis and begin to address Nepal’s pressing socio-economic challenges.

A Direct Mandate and Enhanced Accountability

A directly elected leader would possess a powerful and unambiguous mandate directly from the people of the entire nation, not one derived from backroom deals among a few hundred parliamentarians. This is presented as a more authentic and potent form of democratic legitimacy. Accountability, in this model, is clarified and sharpened. The executive is directly answerable to the electorate at the next election. Their political survival depends on satisfying the public, not on placating coalition partners or maintaining a delicate “parliamentary arithmetic”. This direct link, it is argued, would force the executive to be more responsive to popular concerns and less beholden to the narrow interests of political parties or individual MPs.

Curbing “Horse-Trading” and Legislative Corruption

By creating a clear separation between the executive and legislative branches, a presidential system would fundamentally alter the incentive structure that currently drives political corruption.

In the parliamentary system, the primary ambition of many MPs is to secure a ministerial position, leading to the notorious practice of “horse-trading,” where parliamentary support is exchanged for cabinet posts or other state favors. A directly elected president would form a cabinet independent of the legislature, often appointing experts or technocrats who are not elected officials. This would, in theory, eliminate the market for “buying and selling MPs” and allow the legislature to focus on its core functions: law-making, oversight, and representation, rather than the constant machinations of government formation and dissolution.

National Unity and a Transcendent Leader

A nationwide election for a single executive office would compel candidates to build broad political platforms that appeal to a diverse electorate across Nepal’s many regions, ethnicities, and castes. Unlike parliamentary politics, which can sometimes amplify local or sectarian interests, a presidential campaign requires the construction of a national constituency. The resulting leader, having won a national mandate, could serve as a powerful symbol of unity, embodying the sovereignty of the entire nation rather than just a particular party or coalition. This figure could potentially stand above the fractious identity politics that often paralyzes the legislature, providing a focal point for national identity and purpose.

The intense public support for these arguments is not merely a rational calculation of constitutional mechanics. The call for stability is a proxy for a much deeper societal desire for order, efficacy, and an end to the perceived chaos and corruption that have held the nation back. Decades of political failure have created a vacuum that the public hopes a strong, singular leader can fill. The image of a directly elected executive becomes a vessel for the collective aspiration for a savior—a decisive, incorruptible figure who can finally deliver the development and prosperity that have been promised for so long but have never materialized. This emotional undercurrent makes the debate particularly potent and highly susceptible to populist appeals, transforming a discussion about governance structures into a quest for national renewal.

IV. The Perils of Concentrated Power: The Case Against a Directly Elected Executive

Despite its powerful appeal, the proposal for a directly elected executive in Nepal carries profound risks that could undermine the country’s fragile democracy, deepen social divisions, and create new forms of political dysfunction. Opponents argue that in Nepal’s specific context, concentrating power in a single, popularly elected individual is a cure that could be far worse than the disease.

The Specter of Authoritarianism

The foremost concern is the potential for a directly elected executive to devolve into an “elected autocrat”. Armed with a direct popular mandate, a president could claim to embody the will of the people, using this legitimacy to sideline or overwhelm Nepal’s relatively weak institutional checks and balances, such as the judiciary, the press, and civil society organizations. The country has already had a preview of this danger. Even within the constraints of a parliamentary system, Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli was widely accused of exhibiting authoritarian tendencies, attempting to centralize power under his office, and twice recommending the dissolution of Parliament in moves that were later deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. A directly elected president would face even fewer institutional constraints, making the risk of executive overreach and democratic backsliding significantly higher. While some argue that the Nepali people, having overthrown autocracy before, would rise up against any new dictator, this overlooks the immense social and economic costs of such struggles and the possibility that a determined leader could systematically dismantle democratic guardrails before a popular movement could effectively mobilize.

Threats to Minority Representation and Pluralism

The 2015 Constitution was a historic compromise designed to create a more inclusive state and address the long-standing grievances of marginalized communities. Its core principles are “proportional inclusive and participatory,” aiming to end discrimination based on class, caste, region, language, and gender. A presidential system, with its “winner-take-all” nature, runs directly counter to this foundational ethos. In a presidential election, a candidate can secure 100% of the executive power with just over 50% of the popular vote, leaving the remaining portion of the electorate with no representation in the executive branch.

This is acutely dangerous in Nepal, where political and social cleavages often align with ethnic and regional identities. There is a significant risk that a candidate from the numerically dominant hill-origin upper-caste groups could consistently win the presidency by mobilizing their demographic base. This could lead to the structural exclusion of Madhesi, Janajati, Dalit, and other minority communities from the country’s highest office, deepening their sense of marginalization and potentially reigniting the very conflicts the 2015 Constitution sought to resolve. The current parliamentary system, for all its instability, often forces the major parties to form coalitions with smaller, regional, or ethnic-based parties, ensuring them a share of executive power and a stake in the system. A presidential model would remove this incentive for cross-communal power-sharing at the executive level.

The Inevitability of Executive-Legislative Gridlock

The separation of powers that defines a presidential system is also a recipe for institutional paralysis. It is highly probable that a directly elected president in Nepal would face a legislature controlled by opposition parties, a condition known as divided government. In such a scenario, both the president and the parliament can claim a legitimate democratic mandate from the people, leading to a protracted and debilitating stalemate. The president would be unable to pass key legislation or budgets, while the parliament would be dedicated to obstructing the president’s agenda. Unlike in a parliamentary system, where a vote of no confidence can resolve such a deadlock by forcing new elections or a new government, a presidential system offers no easy escape valve. This “dual legitimacy” crisis can paralyze the state, and in many countries, it has been resolved only through unconstitutional power grabs by one branch or the other.

The Rise of Populism and Personality-Centric Politics

Presidential elections inherently focus public attention on the personal qualities of the candidates—their charisma, background, and rhetoric—often at the expense of substantive policy debate and party platforms. This creates an environment ripe for populist demagogues who can mobilize support by appealing directly to popular emotions, fears, and prejudices. Such leaders often thrive on a politics of division, demonizing opponents and targeting minority groups to build a fervent and loyal base of support. This candidate-centric approach can weaken political parties as institutions, transforming them into mere electoral vehicles for powerful individuals rather than organizations that aggregate interests and develop coherent policy programs.

The very design of the 2015 Constitution was a deliberate attempt to move away from the centralized, unitary, and exclusionary state that had defined Nepal’s history. The introduction of federalism and proportional representation were radical steps to devolve power and guarantee a voice for historically marginalized groups. A “winner-take-all” presidential system would represent a fundamental reversal of this principle. It risks creating a system where a candidate could win the nation’s highest office by appealing exclusively to the majority community, effectively formalizing a majoritarian rule that would be perceived by minority groups not just as a political defeat, but as an existential threat. This could unravel the delicate social compact that underpins the federal republic, undoing the most significant and hard-won achievements of the post-conflict era.

V. A Perennial Debate: The Evolution of Nepal’s Discourse on Governance

The question of whether Nepal should adopt a directly elected executive is not new. It has been a central and deeply divisive issue in the country’s political discourse for well over a decade, particularly during the critical period of constitution-making. Its recent resurgence, amplified by widespread public protest, represents the latest chapter in a long-running debate over the fundamental nature of the Nepali state.

The Constituent Assembly (CA) Era : A Contentious Issue

During the tenure of the two Constituent Assemblies, the form of government was one of the most contentious issues, contributing significantly to the political deadlock that led to the dissolution of the first CA in 2012. The debate within the CA’s Committee on Forms of Government crystallized around three main proposals: a directly elected presidential system, a reformed parliamentary system, and a mixed or semi-presidential model.

- The Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), which emerged as the largest party in the first CA, was the most forceful advocate for a directly elected executive president. They argued that such a system was necessary to end the chronic power struggles, ensure political stability, and balance power centers. Key Maoist leaders, most notably Dr.

Post-2015: Shifting Alliances and Resurfacing Demands

The persistent political instability, frequent changes of government, and widespread corruption that have continued under the 2015 Constitution have breathed new life into the debate.

- Political actors who were previously less vocal on the issue have now joined the call for change. For instance, Upendra Yadav, chairperson of the Janata Samajwadi Party (JSP), now argues that a directly elected executive head and a fully proportional electoral system are necessary to achieve stability and combat the corruption endemic to the current system.

- Most significantly, the demand for a directly elected executive has transitioned from an elite political debate to a grassroots popular movement. The recent “Gen Z” protests, driven by a generation with little patience for the old political games, have adopted this as a core agenda item. This has given the proposal a powerful new momentum and a sense of democratic urgency it previously lacked.

The complex and often tactical nature of these positions is best summarized in a comparative table.

| Political Party / Figure | Stated Position (CA Era, c. 2008-2015) | Stated Position (Post-2015 / Current) | Key Rationale / Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nepali Congress (NC) | Strong and consistent advocate for the Westminster-style parliamentary system. | Maintains its traditional support for the parliamentary system, viewing it as the bedrock of the republic. | Argues that a directly elected executive carries a high risk of authoritarianism and dictatorship. |

| CPN-UML | Officially favored a directly elected Prime Minister in its manifesto, but was inconsistent in negotiations, sometimes siding with the NC’s parliamentary model for tactical reasons. | Position has been less prominent since 2015, as the party and its leader, K.P. Sharma Oli, have operated within and led parliamentary governments. However, Oli’s actions in dissolving parliament were seen by critics as reflecting an impulse for unchecked executive power. | The party’s rationale has shifted with political context, oscillating between the need for stability (justifying a stronger executive) and the practicalities of coalition politics. |

| CPN (Maoist Centre) | The strongest proponent of a directly elected executive president, arguing it was essential for political stability and ending power struggles. | Party leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ has recently reiterated that a directly elected executive chief has been the party’s agenda “since the beginning,” aligning with the demands of the Gen Z movement. | Believes the current system fosters corruption and instability, and that a direct mandate would create a more accountable and effective government. |

| Dr. Baburam Bhattarai | As a leading Maoist ideologue, he was a primary architect of the party’s push for a directly elected executive. | Has remained one of the most consistent and vocal advocates for a directly elected executive presidential system, even after leaving the Maoist party. | Argues it is essential for political stability, national independence, and prosperity, and to overcome the failures of the parliamentary model. |

| Gen Z Movement | N/A | A directly elected executive has emerged as one of the central, “bottom-line” demands of the movement, along with voting rights for the diaspora. | Sees it as a direct solution to end the cycle of instability, corruption, and the dominance of the same elderly leaders, which they believe is caused by the parliamentary system. |

Lessons from the Region and Beyond: Comparative Perspectives

The debate in Nepal does not occur in a vacuum. Other nations, particularly in South and Southeast Asia, have grappled with similar challenges of democratic consolidation, ethnic diversity, and governance under different executive models. Examining their experiences provides invaluable, if cautionary, lessons for Nepal as it considers a fundamental constitutional change.

Sri Lanka: A Cautionary Tale of Presidentialism, Majoritarianism, and Ethnic Conflict

Sri Lanka’s shift from a parliamentary to an executive presidential system in 1978 offers perhaps the most sobering regional parallel for Nepal. The official rationale for the change was twofold: to create a stable, centralized state capable of driving market-oriented economic development free from populist pressures, and to establish an executive powerful enough to rise above the “ethnic outbidding” between the two main Sinhala-dominated parties and find a lasting solution to the Tamil National Question.

The outcome was a stark failure on the second front and a catastrophic one for national unity. Instead of resolving the ethnic conflict, the powerful presidency became an instrument of Sinhala-Buddhist majoritarianism, arguably exacerbating the very tensions it was meant to soothe. The institution itself promoted the ethnic outbidding it was supposed to eliminate, as presidential candidates found that appealing to the Tamil minority carried a severe political risk in mobilizing the Sinhala majority vote. This dynamic deepened the country’s ethnic polarization, contributing to the environment in which a full-blown civil war erupted. The concentration of power in a single individual also led to a significant erosion of democratic checks and balances, with presidents frequently manipulating the constitution to consolidate their authority.

For Nepal, Sri Lanka’s experience serves as a critical warning. It demonstrates that in a deeply divided, multi-ethnic society, a powerful, centralized presidency is not a neutral tool for governance. It can easily be captured by the majority community and used to enforce its will, transforming the state into a vehicle for one group’s aspirations and further alienating minorities, with potentially violent consequences.

The Philippines: A Case Study on “Hyper-Presidentialism,” Political Dynasties, and Systemic Corruption

The Philippines provides another crucial case study of a presidential system in a developing country. Its political system is often described as one of “hyper-presidentials,” where the president wields immense formal and informal power with weak institutional constraints from the legislature or judiciary.

This system has not proven to be a bulwark against two of the country’s most deep-seated problems: the dominance of political dynasties and pervasive corruption. Rather than checking these issues, the powerful presidency often sits at the apex of a system of patronage and rent-seeking. “Strong” presidents, despite running on anti-corruption platforms, have consistently failed to dismantle systemic corruption, often resorting to the selective persecution of political rivals while protecting allies. Political dynasties—powerful families that control political offices across generations—have thrived, using their access to the centralized power of the state to perpetuate their control, distribute patronage, and enrich themselves, often with negative consequences for local development and governance.

The relevance for Nepal is clear. This case demonstrates that a directly elected executive is no panacea for corruption or elite capture. In a context of weak institutions and a deeply embedded political culture of patronage—conditions that are strikingly similar to those in Nepal—a powerful presidency can be co-opted by entrenched elites. It risks becoming the ultimate prize in a political game fought by powerful families, thereby reinforcing and centralizing the very system of corruption and patronage that its proponents claim it will solve.

Indonesia: A Potential Model of Democratic Consolidation in a Diverse Society?

Indonesia’s journey offers a more complex and somewhat more hopeful narrative.

After the fall of the authoritarian Suharto regime in 1998, Indonesia embarked on a democratic transition, adopting a presidential system with direct elections for the president beginning in 2004.Despite its staggering ethnic, religious, and geographic diversity, Indonesia has managed to consolidate its democracy to a remarkable degree, holding regular, competitive elections and maintaining national unity and political stability. The presidential system has provided a stable anchor at the center, avoiding the kind of legislative paralysis seen in other countries. However, Indonesia’s experience is not an unqualified success story. The country continues to struggle with significant challenges, including systemic corruption, the growing influence of political dynasties, and threats to minority rights and civil liberties.

For Nepal, Indonesia’s case suggests that a presidential system is not inherently incompatible with democracy in a highly diverse nation. However, its relative success is likely attributable to a host of other factors unique to its context, such as the specific role of its military in the transition, its particular path of economic development, and a strong, overarching sense of national identity forged through its independence struggle. The persistence of corruption and dynastic politics in Indonesia also serves as a crucial reminder that these problems are not automatically resolved by the choice of executive model.

Global Evidence on Regime Durability

Beyond these specific case studies, broader quantitative research offers a sobering perspective. Cross-national studies have consistently found that, on a global scale, parliamentary democracies have historically proven to be more durable and less susceptible to collapsing into authoritarianism than presidential democracies. This is particularly true for countries at lower levels of economic development, a category into which Nepal falls. This statistical pattern suggests that, from a risk-management perspective, the parliamentary model has a better track record of survival under challenging conditions.

Analysis and Strategic Recommendations for Nepal

Weighing Stability Against Inclusivity: Nepal’s Core Constitutional Dilemma

For Nepal, this is not a choice between a flawed present and an ideal future, but a choice between different sets of risks. The potential gain in executive stability offered by a presidential system must be weighed against the tangible dangers it poses to the country’s delicate social fabric and nascent democratic institutions. The analysis presented in this report suggests that for a nation with Nepal’s specific vulnerabilities—its deep and often politicized ethnic, caste, and regional cleavages, its historically weak and often politicized state institutions, and its living memory of autocratic rule—the risks associated with concentrating immense power in a single, directly elected executive are exceptionally high. The Sri Lankan case vividly illustrates how such a system can become a tool for majoritarian dominance, while the Philippine experience shows its potential to entrench corruption and elite capture. These are not abstract threats; they are direct echoes of the very problems Nepal has struggled for decades to overcome.

Pathways to Reform: Incremental Adjustments vs. Systemic Overhaul

The national discourse has been largely framed as a binary choice between the current dysfunctional parliamentary system and a radical shift to a presidential one. This framing is a false dichotomy. Before undertaking a high-risk systemic overhaul, a more prudent approach would be to explore and implement significant reforms within the existing parliamentary framework to address its most glaring weaknesses. Such incremental reforms could mitigate instability without sacrificing the system’s inclusive character.

- Introduce a Constructive Vote of No Confidence: This is a mechanism, used successfully in countries like Germany, that would require any motion of no confidence against a sitting prime minister to simultaneously name and approve a successor. This would make it significantly harder to topple a government for purely opportunistic reasons, as the opposition would need to agree not just on removing the incumbent but also on who should replace them. This would discourage frivolous no-confidence votes and promote greater stability.

- Reform the Electoral System: The current mixed-member system contributes to legislative fragmentation. A national commission could be tasked with re-evaluating the balance between the First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR) components. For example, slightly increasing the threshold for a party to gain representation under the PR system could reduce the number of small, single-issue parties, thereby encouraging the formation of more stable and coherent coalitions, while still maintaining the principle of inclusivity.

- Strengthen Intra-Party Democracy: A key driver of instability is the top-down, personalized nature of Nepal’s political parties, which often function as the fiefdoms of a few senior leaders. Enforcing existing laws and enacting new ones to mandate and regulate regular, transparent, and democratic internal party elections for leadership positions and candidate selection would make parties more accountable to their members and less susceptible to the whims of their leaders.

Strengthening Institutions: Is the System or the Culture to Blame?

The central argument of this report is that the primary driver of Nepal’s political dysfunction is not the parliamentary model itself, but rather the deeply entrenched political culture of impunity, patronage, and short-termism, which operates within a framework of weak and compromised democratic institutions. A directly elected president would inherit and be forced to operate within this same political ecosystem. Without a fundamental commitment to strengthening the rule of law, a change in the executive model would merely alter the location of concentrated power, not its abusive and corrupt nature. The problem is less about the constitutional blueprint and more about the political actors and the environment in which they operate.

Recommendations for a Structured, Inclusive, and Evidence-Based National Dialogue

The current momentum for change, sparked by the Gen Z movement, offers a historic opportunity for genuine reform. However, this energy must be channeled into a process that is deliberative, inclusive, and evidence-based to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.

- Recommendation 1: Establish an Independent Constitutional Review Commission. The government should immediately establish a high-level, independent commission composed of respected constitutional lawyers, political scientists, sociologists, economists, and representatives of civil society. Its mandate should be to conduct a comprehensive and impartial assessment of the performance of the 2015 Constitution, analyzing its successes and failures, and to formally study the potential impacts of various proposed reforms, including the adoption of a directly elected executive. This commission should be time-bound and its findings made public.

- Recommendation 2: Facilitate Nationwide Public Consultation. The work of the commission must be informed by a structured and extensive process of public consultation. This process must go beyond elite circles in Kathmandu and actively engage with citizens, local governments, and community organizations in all seven provinces, with a special focus on ensuring that the voices of women, Dalits, Janajatis, Madhesis, and other marginalized groups are heard and documented.

- Recommendation 3: Prioritize Immediate Institutional Strengthening. While the constitutional debate proceeds, the government must take immediate and visible steps to address the root causes of public anger by strengthening key democratic pillars. This includes ensuring the full independence and adequate resourcing of the judiciary, the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA), and the Election Commission, as well as initiating meaningful security sector reform to end the culture of impunity.

- Recommendation 4: Any Fundamental Change Must Be Decided by a Referendum. Given the foundational nature of the form of government, any formal proposal to shift from a parliamentary to a presidential or semi-presidential system that emerges from the review process should ultimately be put before the Nepali people for a decision in a national referendum. This step, however, should only be taken after a sustained period of public education and debate, ensuring that voters are fully aware of the well-documented arguments, risks, and potential consequences associated with such a monumental change.

Conclusion: Charting a Democratic Future

The impassioned calls for a directly elected executive in Nepal are a clear and understandable verdict on the failures of the country’s political leadership and the persistent instability of its parliamentary system. The allure of a strong, decisive leader who can deliver stability and development is a powerful force in a nation weary of political dysfunction.

However, this report has argued that surrendering to this allure without a sober assessment of the profound risks would be a historic error. The experiences of other diverse, developing nations, particularly the cautionary tales of Sri Lanka and the Philippines, provide stark warnings. In contexts of deep ethnic division and weak institutional checks, a powerful presidency can become a vehicle for majoritarianism, a catalyst for conflict, and an enabler of systemic corruption and elite capture. For Nepal, a nation whose very constitution is a pact to protect and promote pluralism, the dangers of adopting a “winner-take-all” system are acute. It risks sacrificing the hard-won inclusivity of its democracy on the altar of a stability that may prove to be illusory.

Nepal’s path to a stable, prosperous, and just future does not lie in a constitutional “magic bullet.” No single institutional design can automatically solve problems that are rooted in a political culture of impunity and patronage. The true challenge, and the only sustainable solution, lies in the difficult, patient, and long-term work of building robust and independent institutions, fostering a political culture of accountability and public service, and renewing the social contract between the state and its diverse citizenry. The current debate offers a critical opportunity not just to change the structure of government, but to address the fundamental character of the Nepali state. It is an opportunity that must be seized with wisdom, foresight, and a steadfast commitment to the democratic and inclusive principles for which the Nepali people have struggled for so long.