Democracy, Governance & Development: Economic Prosperity

The Intertwined Destinies of Governance and Growth: A Global Analysis of Political Systems and Economic Prosperity

Introduction

The relationship between a nation’s political system and its economic prosperity is one of the most fundamental and fiercely debated questions in political economy. The query often presents as a paradox: what comes first, democracy or development? Does the establishment of a democratic government in a developed nation naturally lead to the adoption of specific political structures, such as a parliamentary system, or is it that developed nations, having achieved prosperity, then gravitate towards these systems? This report seeks to dissect this complex, cyclical relationship. It moves beyond a simplistic “chicken and egg” framing to explore the nuanced interplay between governance models and economic trajectories.

The central analytical tension lies in the competing claims of different governance systems. On one hand, the 20th century provided compelling examples of authoritarian regimes achieving rapid, state-directed economic modernization, suggesting that concentrated executive power can be a potent tool for “catch-up” growth. On the other hand, a wealth of historical and empirical evidence argues for the long-term superiority of democratic systems in fostering sustainable, inclusive, and innovative economies. This report will navigate this debate by first establishing a clear conceptual framework for governance and development, then examining the major theoretical paradigms that seek to explain their connection. It will proceed through a series of empirical case studies, contrasting the authoritarian development paths of East Asia with the diverse democratic experiences in the West and India. Finally, it will conduct a rigorous comparative analysis of parliamentary versus presidential systems to assess their relative economic efficacy.

This analysis will argue that while authoritarianism can be a powerful instrument for initial industrialization, sustainable prosperity and the transition to a high-income, knowledge-based economy are more robustly supported by democratic institutions. The relationship is not one of simple, unidirectional causality but rather a dynamic feedback loop. Economic changes create profound social shifts that generate pressure for political evolution, and the nature of a nation’s political institutions, in turn, shapes its long-term economic destiny. Ultimately, the evidence suggests that parliamentary systems, in particular, offer an institutional design that fosters the accountability, stability, and inclusivity most conducive to enduring economic success.

Section 1: Defining the Terrain: Governance, Democracy, and Development

To analyze the intricate relationship between political systems and economic outcomes, a precise and nuanced understanding of the core concepts is essential. Governance, democracy, and development are not monolithic categories but complex spectrums with varied historical and contemporary manifestations.

1.1 The Spectrum of Governance: From Authoritarianism to Democracy

At its most fundamental level, democracy is a system of “rule by the people”. This concept, originating in ancient Athens, is built on the key principles of individual autonomy—the right of people to control their own lives—and equality, meaning everyone should have the same opportunity to influence societal decisions. In its modern form, democracy is not merely the act of voting but a comprehensive system characterized by a government that derives its legitimacy from free, fair, and frequent elections; ensures justice and equality before the law; and operates within a constitutional framework of checks and balances on power. While direct democracy exists, the dominant global model is representative democracy, where citizens elect officials to govern on their behalf. It is best understood not as a binary state but as a continuum, where a country can always become more inclusive and more responsive to the will of its people.

In stark contrast, authoritarianism is a form of government defined by highly concentrated and centralized power, maintained through political repression and the exclusion of potential challengers. Such regimes suppress political freedoms and civil rights, shifting power from the populace to a single ruler or a small elite. Authoritarianism often emerges from periods of instability, with leaders promising order and stability at the expense of liberty, frequently resorting to fear and coercion to maintain control. Modern authoritarians have refined their methods, often maintaining the facade of democratic institutions like elections while systematically dismantling checks and balances, politicizing independent institutions, spreading disinformation, and scapegoating minorities—a process of hollowing out democracy from within using “salami tactics”.

1.2 The Mechanics of Representation: Parliamentary vs. Presidential Systems

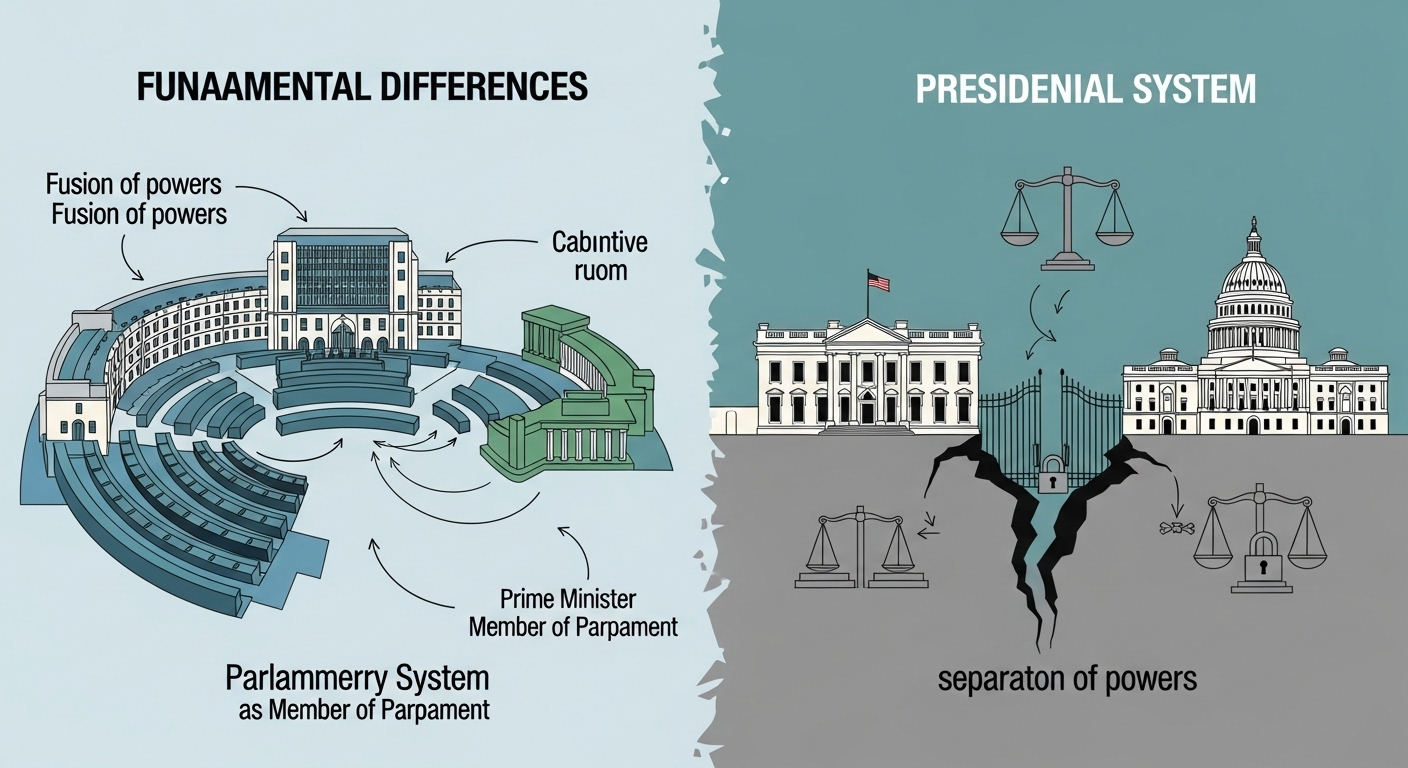

Within the broad category of democracy, the relationship between the executive and legislative branches of government creates a crucial distinction between parliamentary and presidential systems.

A parliamentary system is a democratic model where the executive branch derives its legitimacy from and is constitutionally accountable to the legislature. In this system, there is a fusion of powers; the head of government (typically a Prime Minister or Chancellor) and their cabinet are almost always members of the parliament. This structure creates what is often called a “responsible government,” as the executive is constantly answerable to the legislature through debates and can be removed from office via a “vote of no confidence” if they lose the support of the majority. Originating in Great Britain, this model typically features a separate head of state (a monarch or a ceremonial president) and head of government.

A presidential system, conversely, is characterized by a strict separation of powers between the executive and legislative branches. The president, who is typically the head of both state and government, is popularly elected and holds a fixed term of office. Crucially, the president’s survival in office is not dependent on maintaining the confidence of the legislature, and neither branch can easily remove the other. This “mutual independence” is the defining feature that distinguishes it from the “mutual dependence” of a parliamentary system.

The structural contrast between these two democratic forms is profound. The parliamentary system’s design institutionalizes a more immediate and constant form of accountability through the ever-present threat of a no-confidence vote. This arrangement at the elite level mirrors the broader democratic principle of accountability to the governed and, as will be explored later, has significant implications for policy stability and economic performance. The concentration of power and fixed terms in a presidential system, while offering decisiveness, can also lead to legislative gridlock and greater political volatility.

1.3 Measuring Progress: What Constitutes a “Developed Nation”?

The term “developed nation” or “advanced country” refers to a sovereign state with a high quality of life, a mature economy, and advanced technological infrastructure. Historically, the criteria for this designation have been dominated by economic metrics, such as a high gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, a high gross national income (GNI) per capita, and a high level of industrialization. Developed economies are typically post-industrial, meaning the service sector generates more wealth than the industrial sector.

However, modern definitions increasingly incorporate broader measures of human well-being. The most prominent of these is the Human Development Index (HDI), which provides a composite score based on life expectancy, education levels, and per capita income, offering a more holistic view of development than economic output alone. International organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank classify countries into categories such as “advanced economies” or “high-income economies,” but they often note that these groupings are for statistical convenience and do not represent a definitive judgment about a country’s stage of development. These classifications help to move beyond a simple binary of “developed” versus “developing,” recognizing a spectrum of economic conditions across more than 200 distinct countries.

Section 2: The Great Debate: Theoretical Frameworks of Political and Economic Change

The question of whether economic prosperity fosters democracy or vice versa has been central to political science for decades. Two major theoretical schools of thought, Modernization Theory and Institutional Economics, offer competing frameworks for understanding this dynamic relationship.

2.1 The Modernization Thesis: Does Wealth Create Democracy?

Modernization Theory, which gained prominence in the 1950s and 1960s, posits a direct and often linear relationship between economic development and democratization. The core argument is that as societies become more economically advanced—through processes like industrialization, urbanization, and rising wealth and education levels—their political institutions will inevitably trend towards liberal democracy. As political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset famously argued, “All the various aspects of economic development—industrialization, urbanization, wealth and education—are so closely interrelated as to form one major factor which has the political correlate of democracy”.

The primary mechanism driving this change is social transformation.

Economic growth is believed to create a larger, more educated, and more politically aware middle class. This new class, with its economic independence and desire to protect its property and rights, begins to demand greater political participation and accountability from the state. This process of social mobilization, amplified by urbanization and the spread of mass communication, creates irresistible pressure for political liberalization. W.W. Rostow’s influential model, The Stages of Economic Growth, provided a classic articulation of this presumed universal and unidirectional path, outlining a sequence from “traditional society” to an “age of high mass consumption” that all nations would follow.

2.2 Critiques and Counterarguments: The Limits of a Linear Path

Despite its initial influence, Modernization Theory has faced substantial criticism for its deterministic and simplified view of societal change. A primary critique is its inherent ethnocentrism, specifically a Western bias that presents the development trajectory of Europe and North America as the universal and ideal path for all nations to emulate. This perspective implicitly labels non-Western societies as “traditional” or “backward,” devaluing their unique cultural and historical contexts. Critics argue that development is not a one-size-fits-all process and that the theory’s linear model is overly simplistic, ignoring the complex interplay of local factors.

Furthermore, the theory is faulted for largely ignoring the impact of external global power structures. By treating nations as isolated units developing independently, it fails to account for the legacies of colonialism, imperialism, and ongoing global economic inequalities that fundamentally shape a country’s development possibilities. This critique is the cornerstone of Dependency Theory, which argues that the underdevelopment of some nations is a direct result of their exploitative relationship with developed ones, not an internal failure to modernize.

Empirically, numerous cases contradict the theory’s predictions. The economic rise of authoritarian states like China and Singapore demonstrates that high levels of wealth do not automatically lead to democracy. Conversely, the emergence of “bureaucratic authoritarianism” in some of Latin America’s most developed regions in the 20th century showed that modernization could even lead to democratic breakdown. Indeed, some scholars have argued that authoritarian regimes, by suppressing dissent and mobilizing resources, can at times generate faster economic growth than their democratic counterparts, directly challenging the modernization thesis.

2.3 The Primacy of Institutions: An Alternative Framework for Development

In response to the shortcomings of Modernization Theory, a more nuanced perspective emerged from the field of Institutional Economics. This school of thought contends that the primary determinants of long-term economic performance are a country’s institutions—the formal and informal “rules of the game” that structure human interaction. Formal institutions include constitutions, laws, and property rights, while informal institutions encompass norms, conventions, and codes of conduct.

From this perspective, the causal arrow is reversed or, more accurately, reconfigured. Instead of wealth automatically producing good governance, institutionalists argue that it is the presence of “good” institutions—such as the rule of law, secure property rights, and effective regulatory bodies—that creates the predictable and stable environment necessary for investment and sustained economic growth. Political institutions are paramount because they determine how power is distributed and, therefore, who gets to design and enforce the economic rules.

This framework allows for a more complex, bidirectional relationship between politics and economics. While economic development can increase demand for better institutions, the quality of a nation’s existing political and economic institutions is what ultimately determines its capacity for growth. This institutionalist lens provides a powerful tool for analysis. It helps explain why some authoritarian states can achieve initial success—by imposing order and basic property rights—but may later stagnate due to a lack of accountability and adaptability. It also explains why the specific type of democratic system (parliamentary versus presidential) matters profoundly, as these represent different institutional arrangements that create distinct economic incentives and outcomes. The focus thus shifts from a vague notion of “development” to the specific design of the institutions that govern power.

Section 3: The Authoritarian Path to Prosperity: A Viable Model?

The rapid economic transformations of several East Asian nations under non-democratic rule in the latter half of the 20th century presented a powerful challenge to the notion that democracy is a prerequisite for development. This “developmental dictatorship” model warrants critical examination to understand both its successes and its inherent limitations.

3.1 The East Asian “Miracle”: State-Led Development in South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore

The trajectories of the “Asian Tigers” provide compelling case studies of authoritarian-led modernization.

South Korea: Devastated by war, South Korea was one of the world’s poorest countries in the 1950s. Under the authoritarian leadership of Park Chung-hee, who seized power in a 1961 coup, the nation embarked on a state-led industrialization drive. The government implemented a series of five-year economic plans, pursued an aggressive export-oriented strategy, and fostered a close, collaborative relationship with large family-owned industrial conglomerates known as chaebol. This model produced what became known as the “Miracle on the Han River”, transforming South Korea into an economic powerhouse. However, this rapid development created significant societal change, giving rise to a large, educated middle class and a powerful labor movement. These new social forces began to demand political rights, leading to massive pro-democracy protests that culminated in the end of authoritarian rule in 1987.

Taiwan: Taiwan followed a similar path under the authoritarian one-party rule of the Kuomintang (KMT). The state orchestrated an “economic miracle” by first implementing a successful land reform program and then guiding the economy from light industry in the 1950s and 1960s to a focus on heavy and high-tech industries from the 1970s onward. As in South Korea, decades of economic success created a prosperous and educated middle class that became the driving force for political change. This pressure from below, combined with a process of liberalization from above, led to a remarkably peaceful democratic transition beginning in the late 1980s and culminating in the first direct presidential election in 1996.

Singapore: Singapore represents a significant variation on this theme. Under the long-ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), the city-state transformed itself from a poor colonial outpost into one of the world’s wealthiest nations per capita, all while maintaining a highly authoritarian political system. The Singaporean model of “authoritarian capitalism” masterfully combined a free-market economy, highly attractive to foreign multinational corporations, with a politically repressive state that suppressed dissent and controlled labor. A key state tool was the Central Provident Fund, a compulsory savings scheme that gave the government a vast pool of capital to fund infrastructure projects without relying on foreign debt, thereby creating a highly attractive environment for investment. Singapore stands as a primary case challenging the inevitability of democratization, demonstrating that it is possible to achieve first-world economic status while severely restricting political freedoms.

3.2 The China Enigma: State Capitalism and the “Autocracy Handicap”

The most formidable challenge to the Modernization thesis comes from the People’s Republic of China. Since Deng Xiaoping’s “Reform and Opening Up” policy initiated in 1978, China has experienced an unprecedented economic transformation, lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty and becoming the world’s second-largest economy. This “Chinese miracle” was achieved through a unique system of state capitalism, which combines market-based resource allocation with the unyielding political monopoly of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and significant state control over strategic sectors of the economy. The CPC explicitly uses this record of economic performance as the primary justification for its continued authoritarian rule.

However, the very factors that enabled China’s initial, investment-driven growth may now be evolving into an “autocracy handicap”. Autocratic systems can be exceptionally effective at mobilizing labor and capital for large-scale industrial and infrastructure projects. Yet, as an economy matures, sustained growth depends less on mobilization and more on innovation and productivity gains. This is where the handicap emerges. The arbitrary exercise of state power, crackdowns on private entrepreneurs, a weak rule of law, and the suppression of free inquiry create an environment that is hostile to the risk-taking and creativity necessary for a modern, knowledge-based economy. This raises the critical question of whether China’s model can escape the “middle-income trap”—where growth stagnates after reaching a certain level—without significant political liberalization.

3.3 The Limits of Autocratic Growth: From Initial Success to Long-Term Stagnation

Synthesizing these cases reveals a clear pattern.

The authoritarian development model is a high-variance strategy that appears particularly effective during a specific, early phase of “catch-up” industrialization. By concentrating power, autocrats can override entrenched interests, suppress wages and consumption in favor of forced savings and investment, and direct national resources toward strategic industries.

This model’s core strength—centralized control—eventually becomes its greatest weakness. The absence of accountability and transparency makes such regimes prone to massive corruption and the misallocation of resources on a grand scale. The concentration of power in a single leader or a small clique makes the system brittle, susceptible to catastrophic policy errors, and unable to self-correct. Most critically, as an economy transitions from imitation to innovation, the authoritarian suppression of civil society, free press, and open debate stifles the very creativity and dynamism required for long-term prosperity. The divergent paths of the East Asian cases are illustrative: in South Korea and Taiwan, growing economic complexity and social pressure forced a political opening that allowed them to continue their growth as innovative democracies. In China, the state’s resistance to such an opening raises fundamental questions about the long-term sustainability of its economic model.

Section 4: Democracy’s Dividend: Does Representation Foster Prosperity?

While authoritarianism can deliver rapid but often brittle growth, the historical record of democratic nations suggests a different, more resilient path to prosperity. However, there is no single “democratic model” of development; the sequence and interplay of political and economic liberalization have varied dramatically across countries and historical eras.

4.1 The Western Experience: The Co-evolution of Democracy and Capitalism in the UK and US

The development paths of the United Kingdom and the United States represent two foundational, yet distinct, models of democratic economic development.

United Kingdom: The British case is one of gradual, centuries-long co-evolution. The establishment of key institutional precedents, such as the Magna Carta in 1215 and the Bill of Rights of 1689 following the Glorious Revolution, created a system of parliamentary supremacy and constraints on monarchical power. This political stability and the protection of property rights created a fertile ground for the emergence of a market economy and, eventually, the Industrial Revolution. Full democratization, in the sense of universal suffrage, came much later. The rising economic power of the industrial and commercial middle classes drove the demand for greater political inclusion, leading to a series of Reform Acts in the 19th century that progressively expanded the franchise. In this model, the development of a capitalist market economy preceded and propelled the process of democratization.

United States: The United States represents a contrasting “institutions-first” model. The nation was founded with a democratic-republican framework and strong constitutional protections for private property already in place. This institutional environment fostered a culture of entrepreneurship and facilitated rapid economic growth throughout the 19th century. The government played an active role through the “American System” of tariffs to protect infant industries, a national bank to stabilize finance, and federal investment in infrastructure. While the U.S. path demonstrates how democratic institutions can be foundational to economic development, its history is also marked by deep contradictions, most notably the institution of slavery, which severely retarded the economic and social development of the South for centuries.

4.2 India’s “Precocious Democracy”: Development in a Pluralistic Society

India provides a crucial and unique test case for the relationship between governance and growth. Unlike the East Asian tigers, which developed first under authoritarianism, or the Western nations, which democratized gradually over centuries, India adopted a full-fledged, universal-suffrage parliamentary democracy in 1947 at a very low level of economic development. For its first few decades, India’s economy was characterized by state-led planning and protectionist policies, resulting in sluggish performance often dubbed the “Hindu rate of growth”. The immense challenge of policymaking in a vast, diverse, and decentralized democracy was evident.

However, following significant market-oriented economic reforms in the early 1990s, India’s growth trajectory accelerated dramatically. Many analysts now argue that India’s “precocious democracy,” once seen as a liability, has become a long-term advantage. Its democratic framework has fostered a vibrant private sector, a world-class information technology industry, and a system where the government sets broad objectives while allowing room for private innovation. While challenges of inequality and poverty remain, India’s experience suggests that a democratic system, though potentially slower to mobilize resources initially, can provide the resilience and foundation for robust, market-driven growth in the long run.

4.3 The Democratic Transition: When and Why Authoritarian States Liberalize

The experiences of South Korea and Taiwan demonstrate that while economic development under authoritarianism does not automatically cause democracy, it creates powerful pressures that make a political transition more likely. The process is typically driven by a combination of factors. From below, decades of growth create a large, educated, and urbanized middle class that is less tolerant of arbitrary rule and more organized in demanding political rights and civil liberties. From above, ruling elites may eventually view political liberalization as a necessary step to maintain stability in the face of growing social complexity and protest, or as a way to enhance their legitimacy. Modern economic forces can also play a role; for instance, financial globalization allows economic elites to diversify their assets internationally, reducing their personal stake in defending the domestic autocratic regime from redistributive pressures and thus lowering their resistance to democratization.

These cases challenge a deterministic view. The path is not automatic, but the common thread is that successful economic modernization generates social forces and institutional demands that are ultimately incompatible with a rigid, unaccountable authoritarian system.

Section 5: System Design and Economic Efficacy: The Parliamentary Advantage

While democracy in general is associated with long-term prosperity, the specific institutional design of a democratic government is not a neutral variable. A growing body of evidence indicates that, on average, parliamentary systems are more conducive to positive economic outcomes than their presidential counterparts.

5.1 A Comparative Analysis: Economic Outcomes in Parliamentary vs. Presidential Systems

Quantitative cross-national studies reveal a consistent and statistically significant performance gap between the two democratic models. The data, aggregated from numerous studies, paints a clear picture:

- Economic Growth: Countries with parliamentary systems consistently exhibit higher rates of GDP growth. On average, presidential systems experience growth rates that are 0.6 to 1.2 percentage points lower than parliamentary ones. This seemingly small annual difference compounds over time, leading to a substantial divergence in prosperity. For example, one analysis showed that in 1960, the median real GDP per capita in parliamentary countries was already over four times that of presidential countries; by 2019, that gap had widened even further.

- Inflation: Presidential regimes are associated with higher and more volatile inflation. One major study found that inflation is, on average, six percentage points higher under presidential systems. This macroeconomic instability can erode savings, deter investment, and harm the poorest citizens most acutely.

- Income Inequality: The distributional outcomes are also starkly different. Research indicates that income inequality is between 16% and 20% worse in presidential systems compared to parliamentary ones. This suggests that parliamentary systems are more effective at fostering inclusive growth.

The table below summarizes the mean differences in key macroeconomic indicators from a comprehensive study, illustrating the superior performance of parliamentary regimes.

| Indicator | Presidential Regimes (Mean) | Parliamentary Regimes (Mean) | Difference (Parl. – Pres.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual GDP growth (%) | 1.782 | 2.527 | 0.745 |

| Inflation | 0.142 | 0.070 | -0.072 |

| Income Inequality (Gini) | 43.6 | 35.8 | -7.8 |

Source: Adapted from data in studies by Persson & Tabellini and Bormann. Note: *** indicates the difference is statistically significant. Inflation is a transformed variable. Income inequality is measured by the Gini coefficient.

5.2 Explaining the Difference: Stability, Accountability, and Consensus

This performance gap is not coincidental but stems directly from the foundational institutional differences between the two systems.

First, the fusion of executive and legislative power in parliamentary systems reduces the likelihood of the political “gridlock” that frequently paralyzes presidential systems, particularly under conditions of divided government (when the presidency and legislature are controlled by different parties). Because the executive in a parliamentary system is, by definition, the leader of the legislative majority (or a coalition that forms a majority), it can more efficiently pass its budget and economic agenda.

This leads to greater policy stability and predictability, which is highly valued by economic actors and conducive to long-term investment.

Second, presidential systems, with their fixed terms and winner-take-all elections, can foster a more adversarial and polarized political environment. This can lead to sharp and disruptive policy reversals when power changes hands. In contrast, parliamentary systems, especially those that rely on multi-party coalitions, necessitate continuous negotiation, compromise, and consensus-building to form and maintain a government. This dynamic tends to produce more moderate, centrist policies and fosters more inclusive institutions that represent a broader range of societal interests.

Finally, the mechanism of the “vote of no confidence” provides parliamentary systems with greater flexibility and a more immediate form of accountability. An ineffective or unpopular government can be removed and replaced without waiting for the end of a multi-year fixed term, allowing for quicker course corrections in the face of an economic crisis. This “mutual dependence” between the executive and legislature fosters a cooperative dynamic that is structurally more resilient than the “mutual independence” that can breed conflict in presidential systems.

Conclusion: Synthesizing the Evidence – A Contingent and Cyclical Relationship

What comes first, democracy or development?

The historical record rejects a universal sequence. The paths of the United Kingdom, the United States, the East Asian Tigers, and India demonstrate that nations have arrived at prosperity and democracy through vastly different trajectories. The relationship is best understood as a feedback loop: economic modernization creates social classes and complexities that demand more accountable and representative governance, while robust democratic institutions, in turn, provide the stability, rule of law, and protection of rights necessary for a modern, innovation-driven economy to flourish. The process is contingent on history, culture, and the strategic choices of political actors.

Can executives with absolute power develop a nation more effectively?

The evidence suggests a qualified and time-bound “yes.” Authoritarian regimes have proven highly effective at mobilizing resources for a specific phase of “catch-up” industrialization, as seen vividly in East Asia and China. They can impose high savings rates, direct investment, and suppress dissent to achieve rapid growth. However, this model carries the seeds of its own limitations. The “autocracy handicap“—a vulnerability to corruption, policy error, and an inability to foster the innovation required for advanced economic status—poses a significant long-term risk. For achieving sustainable, high-income prosperity, democracy, with its mechanisms for accountability and self-correction, is the superior system.

Do developed nations later implement parliamentary systems?

This framing implies a passive evolution, but the evidence suggests a more active and causal relationship. While the parliamentary system was the product of a long historical evolution in its birthplace, the United Kingdom, the comparative data is now clear: as an institutional choice, parliamentary democracy is more effective at delivering positive economic outcomes. Nations do not simply drift toward this model; rather, the evidence strongly indicates that for a country seeking to maximize economic growth, macroeconomic stability, and social equity within a democratic framework, the parliamentary system is the superior institutional design. Its inherent advantages in promoting policy stability, fostering consensus, and ensuring executive accountability create an environment more conducive to long-term prosperity than the conflict-prone structure of presidentialism.

The ultimate determinant of both durable democracy and sustained development is the quality of a nation’s institutions. The core lesson is that inclusive political institutions—those that distribute power broadly and hold leaders accountable—are the most reliable foundation for creating inclusive economic institutions, which in turn generate shared and sustainable growth. The global evidence strongly suggests that parliamentary democracy is the most effective and resilient system yet devised for building and maintaining these vital institutions.