Jekyll Front Matter: YAML’s Power & Usage Explained

Unlocking the Data Layer: A Comprehensive Guide to YAML Front Matter in Jekyll

The Foundation: Defining and Structuring Front Matter

At the core of Jekyll’s processing model lies a simple yet powerful convention known as front matter. It serves as the primary signaling mechanism that distinguishes a passive file to be copied from a dynamic document to be rendered. This section establishes the conceptual and syntactical foundation of front matter, detailing its role as Jekyll’s processing trigger and exploring the expressive capabilities of YAML, the language that gives this metadata its structure and power.

The Front Matter Block: Jekyll’s Processing Signal

Any file that contains a YAML front matter block is treated by Jekyll as a special file requiring processing. The front matter must be the very first thing in the file and takes the form of a valid YAML snippet placed between two triple-dashed lines. This block’s presence is the essential trigger that instructs Jekyll to run the file through its conversion pipeline—transforming Markdown into HTML, for instance—and to process any embedded Liquid templating tags. This authoring convention, popularized by Jekyll, has become so influential that it has been adopted by a wide array of other static site generators and content management systems, establishing it as a de facto standard for embedding metadata within content files.

The role of front matter as a processing signal is so fundamental that its presence is required even when no specific metadata is needed for a particular file. For files such as CSS, RSS feeds, or simple pages that need to access site-wide Liquid variables but do not have unique variables of their own, an empty front matter block is used.

YAML

---

---

This empty block serves no data-provisioning purpose but successfully triggers Jekyll’s processing engine, making global variables like site.title available within the file. This illustrates a core design principle of Jekyll: the build process is explicit. The developer must clearly signal which files are dynamic. This deliberate choice ensures a predictable build process, but it can introduce a small amount of friction for simpler use cases. This friction, the need for boilerplate in every processable file, has in turn fostered a plugin ecosystem to address it. Tools like jekyll-optional-front-matter exist specifically to automate this signaling process for Markdown files, effectively altering Jekyll’s core philosophy of explicitness in favor of convenience for those who opt in. This reveals a fundamental tension between a tool’s design for predictability and user demand for streamlined workflows, a common dynamic in the evolution of software development tools.

YAML Fundamentals: The Language of Metadata

Front matter uses YAML (a recursive acronym for “YAML Ain’t Markup Language”), a human-readable data serialization language. Its clean, indentation-based syntax makes it ideal for managing configuration and metadata.

Core Syntax and Structure

The basic unit of YAML is the key-value pair, separated by a colon and a space (key: value). The structure of the data is defined by indentation. A critical rule, and a common source of errors, is that YAML uses spaces for indentation, not tab characters. Consistent indentation is essential for defining the nesting of data, particularly in more complex object structures.

To improve the readability and maintainability of front matter, comments can be added using the hash symbol (#). Any text following a # on a line is ignored by the parser.

YAML

---

# This is a comment explaining the purpose of the title variable.

title: Home

---

```Character Encoding Considerations

A crucial technical detail, especially for developers working on Windows, is character encoding. All files should be saved with UTF-8 encoding. Furthermore, it is imperative to ensure that no Byte Order Mark (BOM) header characters exist in the files. The presence of a BOM can lead to parsing failures and “very, very bad things” during the Jekyll build process.

Mastering Data Types: From Simple Values to Complex Structures

YAML’s power lies in its support for a rich set of data types, allowing developers to define everything from simple flags to deeply nested data structures directly within a content file’s front matter.

Primitive Types

- Strings: Textual data. Quotation marks are often optional but become necessary when a string could be misinterpreted as another data type (e.g., “5.0” to ensure it’s treated as a string, not a number) or when it contains special characters. For strings containing a single quote, the YAML-preferred escaping method is to double the single quote (‘O”Malley’). Alternatively, the entire string can be enclosed in double quotes (“O’Malley”).

- Numbers: Both integers (e.g., 5) and floating-point numbers (e.g., 4.1) are supported.

- Booleans: The values true and false are used for logical flags.

Complex Structures

- Arrays (Lists): An ordered sequence of items. YAML provides two syntaxes for arrays. The more common vertical, or block, style uses a hyphen and a space to prefix each item on a new line. The inline style uses square brackets with comma-separated values […]. Arrays are fundamental for variables like

tagsorcategories. - Objects (Maps/Dictionaries): Collections of key-value pairs, used to create nested, structured data. Indentation is used to define the structure of the object. This allows for the creation of rich data entities, such as a detailed author profile with multiple attributes.

Handling Multiline Text

For text that spans multiple lines, such as a detailed description or a block of custom code, YAML provides two special block scalar styles:

- Folded Style (>): This style converts newlines within the text block into spaces, effectively “folding” the text into a single long string. It is ideal for paragraph-style text where line breaks in the source code are for readability only. The variant

>-also removes the trailing newline. - Literal Style (|): This style preserves newlines, making it suitable for content where line breaks are significant, such as poetry or pre-formatted text. The variant

|-removes the trailing newline. When using the literal style to embed Markdown that needs to be rendered as HTML, it is often necessary to apply themarkdownifyLiquid filter in the template (e.g.,{{ page.my_multiline_text | markdownify }}) to ensure the content is processed correctly.

The following table provides a consolidated reference for YAML data type syntax within Jekyll front matter.

| Data Type | Syntax Example | Notes / Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| String | title: "My Awesome Post" |

Quotes are optional for simple strings but required for ambiguity. |

| Number | version: 2.1 |

Can be an integer or a float. |

| Boolean | published: true |

Must be true or false (unquoted). |

| Array (Vertical) | tags: |

Preferred for readability with multiple items. |

| Array (Inline) | tags: [jekyll, webdev] |

Convenient for short lists. |

| Object | author: |

Indentation defines the nested structure. |

| Multiline (Folded) | description: >- |

Line breaks become spaces. Ideal for paragraphs. |

| Multiline (Literal) | code_snippet: |- |

Line breaks are preserved. Ideal for code or poetry. |

Jekyll’s Predefined Variables: The Core Control System

Jekyll provides a set of predefined front matter variables that act as a core control system, directly influencing how pages and posts are rendered, organized, and structured within the final site. These variables are the primary interface for interacting with Jekyll’s built-in logic for layouts, URLs, and content organization. Understanding this reserved vocabulary is essential for effectively managing a Jekyll project.

Global Variables: Controlling Page Rendering and Identity

These variables are applicable to any file being processed by Jekyll, including pages, posts, and items in collections. They control the fundamental aspects of a document’s presentation and location.

- layout: This is arguably the most critical variable in Jekyll’s templating system. It specifies the name of a layout file within the

_layoutsdirectory (used without the.htmlfile extension) that will be used to wrap the content of the current file. This mechanism allows for the creation of reusable site structures (headers, footers, sidebars) and is the foundation of the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle in Jekyll. Thelayoutvariable also supports special values:nullwill render the file without any layout, andnone(available since Jekyll 3.5.0) will also produce a file without a layout, with the added behavior of overriding any layout specified in front matter defaults. - permalink: This variable provides granular control over the output URL of a page or post, overriding Jekyll’s default URL generation scheme. For posts, the default is typically

/year/month/day/title.html. By settingpermalink: /about/my-custom-path/, a developer can create clean, human-readable URLs that are independent of the file’s location or date, a crucial feature for search engine optimization (SEO) and logical site architecture. - published: This boolean variable acts as a toggle for content visibility. If set to

published: false, the specific post or page will be excluded from the site during the build process. This is an invaluable tool for drafting content, allowing authors to commit unfinished work to version control without it appearing on the live site.

“`

“`html

To preview this unpublished content locally, one can run the Jekyll server with the –unpublished flag.

Post-Specific Variables: Organizing Chronological Content

Jekyll’s “blog-aware” nature is most evident in a set of variables designed specifically for managing posts within the _posts directory.

- date: While Jekyll can infer a post’s date from its filename (e.g., 2023-10-27-my-post.md), the date variable allows for a more precise timestamp to be set. This overrides the filename-inferred date and is crucial for ensuring correct chronological sorting of posts. The value must be specified in the format YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM:SS +/-TTTT, though the time and timezone components are optional.

- category / categories: These variables are used to assign a post to one or more high-level content groups. Instead of relying solely on physical folder structures for organization, categories provide a flexible, metadata-driven approach. The singular

categorykey accepts a single value, while the pluralcategorieskey can accept either a YAML list or a space-separated string of multiple category names. Jekyll uses this data to populate thesite.categoriesvariable, enabling the creation of category-based archive pages. - tags: Similar in function to categories, tags allow for more granular, non-hierarchical labeling of posts. A post can have multiple tags, which are useful for describing its specific topics. Like categories, the

tagsvariable accepts either a YAML list or a space-separated string and populates thesite.tagsvariable for use in templates.

The specific design of these predefined variables tells a story of Jekyll’s origins and its subsequent evolution. The prominence of date, categories, and tags points to its initial focus as a tool for bloggers. However, the abstract and powerful nature of global variables like layout and permalink provided the foundation for Jekyll to grow beyond this niche. These tools allow developers to effectively disable the “blog” features and use Jekyll to build any type of static site, from documentation portals to e-commerce front-ends, by defining custom content structures and URL schemes.

Implicit Variables: De Facto Standards

In addition to the officially documented predefined variables, the Jekyll ecosystem has established several de facto standards that, while not hardcoded into the Jekyll core, are universally recognized by themes and essential plugins.

- title and description: These are the most common examples. Nearly every Jekyll theme and layout expects a

titlevariable to be present for use in the HTML<title>tag and the main<h1>heading of a page. Similarly, adescriptionorexcerptvariable is widely used by SEO plugins, such as the popular jekyll-seo-tag, to populate the<meta name="description">tag. The power of these variables comes not from a core implementation but from community consensus, a testament to the organic evolution of best practices within the Jekyll ecosystem.

The following table serves as a comprehensive reference for Jekyll’s predefined and de facto standard front matter variables.

| Variable | Data Type | Scope | Function and Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| layout | String | Global | Specifies the layout file from _layouts. Special values: null (no layout), none (no layout, overrides defaults). |

| permalink | String | Global | Overrides the default output URL for the page/post. |

| published | Boolean | Global | If false, the file is excluded from the site build. |

| date | Date String | Posts | Overrides the date from the filename. Format: YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM:SS +/-TTTT. |

| category | String | Posts | Assigns the post to a single category. |

| categories | Array / String | Posts | Assigns the post to multiple categories (as a list or space-separated string). |

| tags | Array / String | Posts | Assigns one or more tags to the post (as a list or space-separated string). |

| title | String | Global (De Facto) | The main title of the page/post, used in headings and HTML <title>. |

| description | String | Global (De Facto) | A brief summary used for meta descriptions and SEO. |

Unleashing Custom Variables: Tailoring Content and Functionality

Beyond the predefined control variables, the true power of front matter lies in its capacity to hold arbitrary, custom-defined data. By defining their own variables, developers can create rich, structured metadata schemas tailored to their specific content needs. This transforms each content file from a simple document into a self-contained, structured data record, effectively turning a Jekyll site into a “flat-file Content Management System (CMS).”

This architectural pattern, where content (Markdown) and metadata (YAML) coexist within the same version-controlled file, represents a significant paradigm shift from traditional database-driven systems. Instead of separating content and metadata into different database tables, the file itself becomes the atomic unit of data. This approach leverages the file system as a database and a text editor as the content management interface, offering profound benefits in developer workflow, versioning with Git, performance, and security.

Defining and Scoping Custom Variables

The mechanism for creating custom variables is straightforward: any valid YAML key-value pair included in the front matter that is not a predefined Jekyll variable is automatically registered as a custom variable. These variables are then made accessible within the Liquid templating context through the page object.

For example, adding author: "John Doe" to a post’s front matter allows for its value to be rendered in a template using the Liquid tag {{ page.author }}.

Use Case: Advanced Author and Contributor Metadata

For a multi-author blog or a documentation site with various contributors, a simple author string is insufficient. A more robust solution involves defining the author as a YAML object with nested properties.

YAML

---

author:

name: Dr. Eleanor Vance

affiliation: Institute for Static Web Studies

twitter_handle: evance_web

avatar_url: /assets/images/authors/evance.jpg

---

This structured data can then be used in a reusable _includes/author_bio.html partial, which can render a rich author box with a name, affiliation, and social media links, all driven by the data in the post’s front matter.

Use Case: Implementing Feature Flags and Conditional Content

Custom boolean variables serve as powerful feature flags, allowing for page-level control over a site’s features and layout. A developer can toggle the visibility of elements like a table of contents, a promotional banner, or a comments section on a per-page basis.

YAML

---

title: Advanced Installation Guide

show_toc: true

featured_post: true

comments_enabled: false

---

In the corresponding layout file, Liquid conditional logic can then be used to render these elements only when the flag is set to true.

Code snippet

{% if page.show_toc %}

{% include table_of_contents.html %}

{% endif %}

This technique turns front matter into a dynamic control panel for each page, enabling significant layout variations without requiring separate layout files.

Use Case: Managing Page-Specific Assets and SEO

Front matter is the ideal location for managing metadata related to page-specific assets and search engine optimization.

- Featured Images: Instead of just a simple image path, a structured image object can store comprehensive data, including the path, alternative text for accessibility, dimensions, and custom classes. This provides all the necessary information to render a fully compliant and responsive image tag.YAML

--- image: path: /assets/images/featured/server-racks.png alt: "Racks of servers in a data center." width: 800 height: 450 class: shadow-none --- - Granular SEO Control: Custom variables can be defined to override site-wide SEO settings. Variables like

meta_description,keywords, andcanonical_urlcan be set on individual pages and then injected into the<head>of the final HTML document, providing precise control over how search engines index the content. - Custom Code Injection: Using YAML’s multiline string syntax, page-specific CSS or JavaScript can be embedded directly in the front matter. This code can then be outputted within

<style>or<script>tags in the site’s layout, allowing for targeted styling or functionality without cluttering global asset files.

Use Case: Driving Navigation and Content Relationships

Custom front matter variables can be used to manage the site’s structure and create explicit relationships between different pieces of content.

- Navigation Ordering: By default, when iterating through

site.pages, the order is alphabetical. A custom variable such asnav_order: 2can be used to assign a numerical weight to pages. The navigation include can then use a Liquid filter to sort the pages based on this variable, creating a manually curated menu order.Code snippet{% assign sorted_pages = site.pages | sort: "nav_order" %} {% for p in sorted_pages %} <a href="{{ p.url }}">{{ p.title }}</a> {% endfor %} - Content Relationships: To create “Related Posts” sections that are more specific than what tag or category matching can provide, an array variable like

related_postscan be used to manually list the slugs or IDs of other relevant articles. The template can then loop through this array to find and display links to the specified posts.

The Liquid Interface: Accessing and Rendering Front Matter Data

Once data is defined in the YAML front matter, the Liquid templating language provides the necessary tools to access, manipulate, and render that data in the final HTML output.

“`

“`html

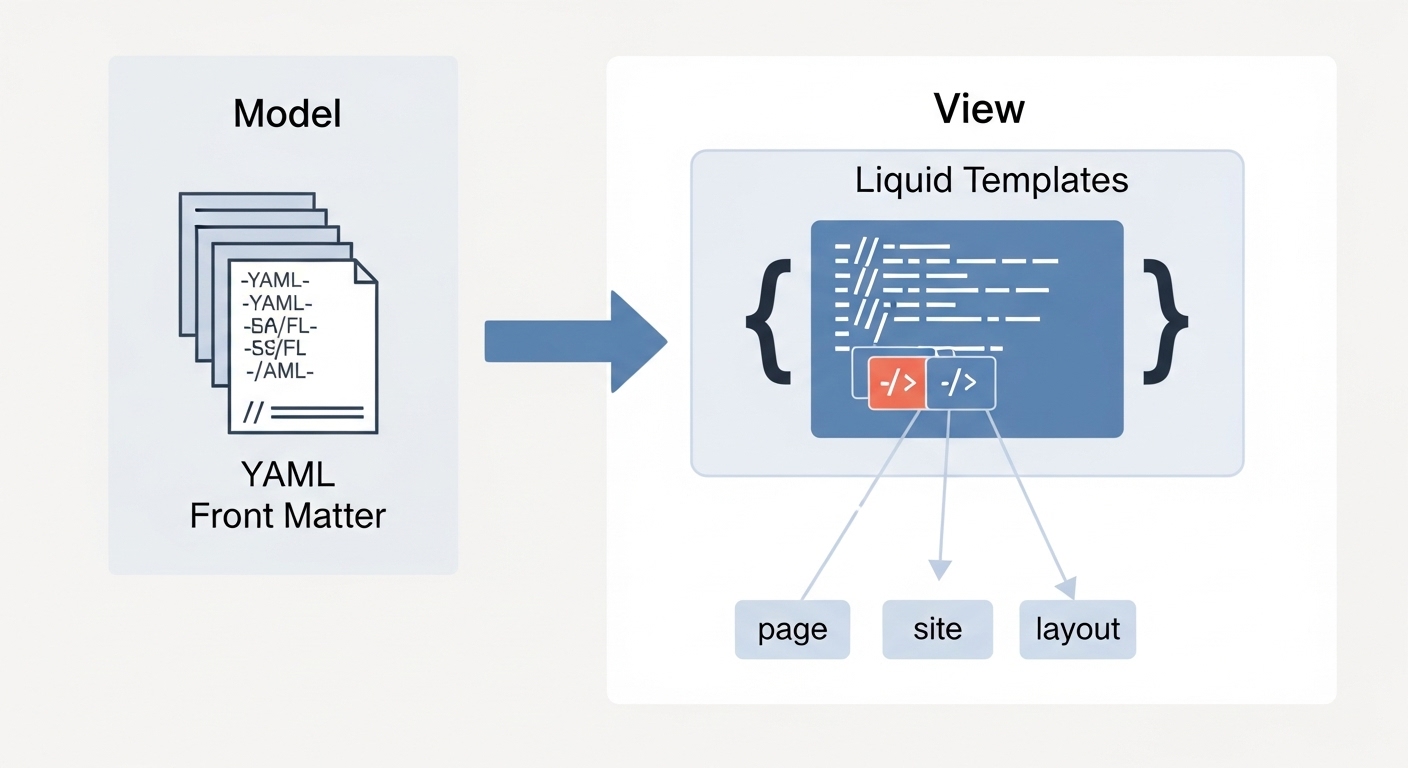

The relationship between front matter and Liquid is fundamental to Jekyll; front matter provides the “model” (the data), while Liquid operates in the “view” (the template) to create the presentation layer. This one-way data flow—from static YAML definitions into the dynamic Liquid rendering context—is a deliberate architectural choice that ensures a simple, predictable build process. It prevents complex circular dependencies and makes template logic easier to trace and debug.

The Global Objects: Your Gateway to Data

- page: This is the most frequently used object. It acts as a hash containing all the front matter variables defined in the specific file currently being processed by Jekyll. Any custom variable, such as author, is accessed via page.author. Predefined variables like title and layout are also available under this object (e.g., {{ page.title }}).

- site: This object contains site-wide information and configuration settings from the _config.yml file. It also holds aggregated data from across the entire site, such as site.posts (an array of all post objects), site.pages (an array of all page objects), and site.categories (a hash of all categories and their associated posts).

- layout: This object contains the front matter variables that are defined within the layout file being used to wrap the current page. This allows layouts themselves to have their own metadata.

Rendering Simple Variables and Object Properties

The most common way to access and render data is through dot notation. This syntax is used to access top-level variables from an object or to traverse into nested objects.

- Top-level variable: {{ page.title }}

- Nested object property: {{ page.author.name }}

An alternative syntax, bracket notation, is also available: {{ page[‘title’] }}. This is particularly useful when the key to be accessed is itself stored in a variable.

Iterating Over Arrays with Loops

To render the contents of an array, such as a list of tags or a collection of product features, Liquid’s for loop is essential.

Code snippet

<ul>

{% for tag in page.tags %}

<li>{{ tag }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

This same construct can be used to iterate over an array of objects. Within the loop, the properties of each object can be accessed using dot notation.

Code snippet

<div class="authors-list">

{% for author in page.contributors %}

<div class="author">

<img src="{{ author.avatar_url }}" alt="Avatar for {{ author.name }}">

<p>{{ author.name }}</p>

</div>

{% endfor %}

</div>

Implementing Logic with Conditionals

Liquid’s conditional tags—if, unless, elsif, and else—allow template logic to be controlled by the values in the front matter. This is commonly used with boolean flags to show or hide entire blocks of HTML.

Code snippet

{% if page.comments_enabled == true %}

<section id="comments">

</section>

{% endif %}

Liquid supports standard comparison operators (==, !=, <, >) as well as the contains operator, which can check for the presence of a substring within a string or an item within an array.

Code snippet

{% if page.tags contains "featured" %}

<span class="featured-badge">Featured</span>

{% endif %}

Advanced Topic: The Limitation of Liquid within Front Matter

A crucial concept to understand is that Jekyll, by default, does not process Liquid tags inside the YAML front matter block. A definition like title: "A Post About {{ site.product_name }}" will not work as expected; the output will be the literal string, not the rendered value.

This limitation is a direct consequence of Jekyll’s build order. The front matter of a file is parsed first to collect all necessary metadata. This data is then used to populate the page variable before the Liquid rendering engine begins processing the file’s content and layout. This strict sequence prevents the circular dependencies that could arise if front matter variables depended on other Liquid-rendered variables.

While this architecture ensures predictability, advanced use cases sometimes require more dynamic data composition. Several workarounds exist to address this limitation:

- Client-Side JavaScript: A simple but often undesirable approach is to render a placeholder in the HTML and use JavaScript to populate it on the client side. This is generally discouraged as it can negatively impact SEO, since search engine crawlers may index the page before the JavaScript has executed.

- Jekyll Plugins: For environments where custom plugins are permitted (i.e., not the default GitHub Pages environment), plugins provide the most robust server-side solution. A plugin like jekyll-liquify or a custom-written filter can be created to add a post-processing step that explicitly parses and renders Liquid within specified front matter variables. This approach retains the benefits of server-side rendering while enabling more dynamic metadata.

Centralized Control with Front Matter Defaults

For any project larger than a few pages, repeating the same front matter variables—such as layout: post or author: "Your Name"—in every file is inefficient and error-prone. Jekyll provides a powerful solution to this problem through its defaults configuration key in the _config.yml file. This feature allows developers to define default front matter values that are programmatically applied to files based on their path and type, embodying the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle at a site-wide architectural level.

Mastering front matter defaults elevates a Jekyll project from a mere collection of files into a cohesive, architected system. It enables a “site architecture as code” paradigm, where content rules and metadata are defined centrally in a single, version-controlled configuration file. This declarative approach—stating a rule like “all files in the _posts directory shall use the post layout”—is vastly more scalable and maintainable than the imperative approach of manually editing each file.

The defaults Configuration Key: Scope and Values

The defaults key in _config.yml holds an array of objects, where each object is a scope/values pair.

- The scope defines a set of criteria to target specific files within the project.

- The values object contains the key-value pairs of front matter variables that will be applied to all files matching that scope.

YAML

# In _config.yml

defaults:

-

scope:

path: ""

type: "posts"

values:

layout: "post"

comments_enabled: true

Applying Defaults by Path and Type

The scope is defined using two primary keys: path and type.

- Scoping by path: This key targets files based on their location within the project directory.

- An empty string (

path: "") sets a global scope, targeting all files in the project. - A specific folder name (

path: "projects") targets all files within that folder and its subfolders. - Scoping by type: This key filters the files within the specified path based on their Jekyll collection type. Valid types include the built-in

pages,posts, anddrafts, as well as the pluralized name of any custom collection defined in the configuration (e.g.,my_collectionfor a collection namedmy_collection).

These two keys can be used in combination to create highly specific targeting rules. For example, one could apply one set of defaults to all pages in the site, and a different, more specific set of defaults to pages within the projects path.

Precedence Rules: The Cascade of Configuration

Jekyll applies defaults using a clear order of precedence, ensuring that configurations cascade in a predictable manner.

- Base Defaults: The process begins with the defaults defined in

_config.yml. - Scope Specificity: Within the defaults configuration, more specific path scopes override broader ones. For example, a default set for

scope: { path: "projects" }will take precedence over a default for the same variable set forscope: { path: "" }for any file inside the projects folder. - Page-Level Front Matter: The final and highest level of precedence is the front matter written directly within a content file. Any variable explicitly set in a page’s front matter will always override any value for that same variable set via the defaults configuration.

This cascade allows for a flexible yet powerful system where global rules can be established, with specific sections of the site overriding those rules, and individual pages having the final say.

Advanced Scoping with Glob Patterns

Since Jekyll 3.7.0, the path key in a scope definition can use glob patterns for even more granular file matching. This allows for the creation of complex rules, such as targeting all files with a specific name across multiple subdirectories (path: "section/*/special-page.html"). While powerful, it is important to note that using glob patterns can have a negative impact on build performance, particularly on large sites or on the Windows operating system, as it requires more complex file system traversal.

The following table summarizes the properties used to define a scope for front matter defaults.

| Property | Data Type | Description and Examples |

|---|---|---|

path |

String |

Defines the file path to target. An empty string ("") targets all files. |

“`

A folder name (“articles”) targets all files in that directory. Glob patterns (“docs/*/”) can also be used.

type

String

Filters files within the specified path by their collection type. Valid values include pages, posts, drafts, or the name of a custom collection (e.g., “portfolio_items”).

Conclusion

Jekyll’s front matter is far more than a simple mechanism for adding metadata to a page. It is the foundational data layer that elevates Jekyll from a basic file converter to a sophisticated, data-driven static site generator. By embracing the expressive power of YAML, developers can define a rich, structured schema for their content, transforming individual Markdown files into self-contained data records. This approach fosters a “flat-file CMS” architecture, which offers significant advantages in version control, portability, performance, and security over traditional database-driven systems.

The journey from a basic understanding to mastery of front matter follows a clear progression. It begins with the core concept of the front matter block as Jekyll’s primary processing signal and the use of predefined variables like layout and permalink to control the fundamental structure of the site. It then expands to the creation of custom variables, which unlock the ability to implement advanced features such as conditional content rendering, detailed author profiles, granular SEO controls, and curated navigation systems.

The interaction between this data layer and the presentation layer is managed through the Liquid templating language, which provides the necessary tools for accessing, iterating, and logically processing front matter variables. While the one-way data flow from YAML to Liquid imposes certain limitations, it is a deliberate architectural choice that ensures a predictable and debuggable build process.

Finally, the defaults configuration in _config.yml provides the mechanism for scaling this data-driven approach across an entire site. By centralizing the definition of front matter variables, developers can enforce consistency, reduce repetition, and manage the architecture of hundreds or thousands of pages from a single, declarative configuration file.

Ultimately, a deep understanding of front matter—from its basic syntax to its role in site-wide architecture—is the definitive characteristic of an expert Jekyll developer. It is the key to unlocking the full potential of static site generation, enabling the creation of websites that are not only fast and secure but also highly structured, maintainable, and dynamically controlled by the data embedded within their very content.

📚 For more insights, check out our web development best practices.