Research Book Summaries: Craft of Research & Diffusion

Part I: An Introduction to Foundational Frameworks

1.1 Situating the Seminal Texts

In the landscape of academic thought, certain works achieve a foundational status, providing the essential frameworks through which entire fields of inquiry are understood and practiced. Two such texts, Everett M. Rogers’s Diffusion of Innovations and The Craft of Research by Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams, stand as pillars in their respective domains. Though they address seemingly disparate subjects—one the macro-level social process of how new ideas spread, the other the micro-level intellectual process of how sound arguments are built—they are deeply complementary. Together, they offer a comprehensive toolkit for the modern researcher, explaining both the phenomena to be studied and the rigorous methods by which that study should be conducted.

Diffusion of Innovations, first published in 1962, is the classic, seminal work on the spread of new ideas. Originating from communication studies but drawing from a wide array of disciplines, Rogers’s theory seeks to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technologies are adopted by participants in a social system. Its coverage is comprehensive, ranging from the core elements of the diffusion process to the characteristics of adopters and the consequences of innovation. The theory’s robust explanatory power has made it a cornerstone in fields as diverse as public health, where it has been used to promote hygiene and family planning; agriculture, where it explained the adoption of hybrid corn; and technology, where it helps predict the success of new inventions. The book’s enduring relevance is demonstrated by its fifth edition, which has been updated to address the unprecedented speed of diffusion in the internet age, a force that is fundamentally transforming human communication and the very nature of the diffusion process itself.

Parallel to this exploration of social change is The Craft of Research, a work described as an “unrivaled resource” for researchers at every level, from first-year undergraduates to professionals in business and government. First published in 1995, it has become a standard text in academic composition, providing a fundamental and practical guide to the entire research lifecycle. The book demystifies the research process, explaining how to move from a general interest to a significant topic, how to pose productive questions, find and evaluate sources, build sound and compelling arguments, and communicate those arguments effectively to an audience. Like Diffusion, The Craft of Research has evolved to meet the needs of contemporary scholars. Its latest edition acknowledges that research outputs may not always be traditional papers and addresses the challenges and opportunities presented by new technologies, including guidelines for the use of generative AI, while expanding its discussion on the ethical obligations of researchers.

1.2 Report Thesis: A Synthesis of “How Ideas Spread” and “How to Argue About Them”

While these two works are often studied in isolation, their true power emerges from their synthesis. This report advances the thesis that a mastery of the methodological principles articulated in The Craft of Research is indispensable for rigorously investigating, analyzing, and communicating the complex social phenomena described in Diffusion of Innovations. The frameworks of claim, reason, evidence, and warrant are the essential tools for transforming observations of diffusion into credible, scholarly knowledge. Conversely, a deep understanding of Rogers’s diffusion theory provides researchers with a critical meta-framework for navigating their own academic environments. It allows them to comprehend how their own scholarly contributions—their research “innovations”—are adopted, challenged, and disseminated within the unique “social system” of their academic discipline.

This analysis therefore explores the profound synergy between the “what” (the process of social diffusion) and the “how” (the craft of researching and arguing about that process). It posits that these two books represent a fundamental duality in the creation and dissemination of knowledge. Diffusion of Innovations describes the external, social process by which knowledge and practices move through a population, while The Craft of Research prescribes the internal, intellectual process by which an individual researcher constructs and validates a single piece of knowledge. They are not separate subjects but two integral sides of the same coin. To make a valid claim about why an innovation failed to diffuse—for example, the Dvorak keyboard mentioned by Rogers—a researcher cannot simply state an opinion. They must structure their analysis as an argument, following the blueprint provided by Booth, Colomb, and Williams. This would involve a central claim (e.g., “The Dvorak keyboard failed to achieve widespread adoption primarily due to its incompatibility with the established QWERTY infrastructure and a lack of perceived relative advantage sufficient to overcome switching costs”). This claim must be supported by reasons (e.g., the vast installed base of QWERTY typewriters, the prohibitive cost of retraining typists) and substantiated with evidence (e.g., historical market data, economic analyses of switching costs, contemporary reports from the era). The researcher must also anticipate and respond to counterarguments, such as the claim that Dvorak is objectively more efficient. The quality of this “craft” directly determines the validity of our understanding of “diffusion.” A poorly constructed argument about a diffusion process remains an anecdote; a well-crafted one becomes a contribution to knowledge.

Part II: The Anatomy of Social Change: A Deep Dive into Diffusion of Innovations

2.1 The Diffusion Process: Core Concepts and Definition

At the heart of Everett M. Rogers’s theory is a clear and powerful definition that has become a cornerstone of communication and social science research. Diffusion is defined as “the process in which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system”. This definition is not merely descriptive; it is analytical, breaking down a complex social phenomenon into four constituent elements—the innovation, communication channels, time, and the social system—that serve as the foundational pillars of the entire theory. Each of these elements provides a distinct lens through which to analyze the success or failure of a new idea’s spread.

A central, unifying theme that runs through the entire theory is the concept of uncertainty. Rogers explains that new ideas are initially perceived as uncertain and even risky by potential adopters. The inherent newness of an innovation means that individuals cannot be sure of its consequences, leading to a state of ambiguity that they are motivated to resolve. The diffusion process, therefore, can be understood as a large-scale social mechanism for managing and reducing this uncertainty. To overcome their apprehension, most people seek out information and social proof from others like themselves who have already adopted the new idea. The decision to adopt is fundamentally a process of dealing with the uncertainty involved in choosing a new alternative over an existing, familiar one. The various components of the diffusion model are, in effect, the tools and stages through which individuals and social systems collectively convert the unknown into the known, transforming a risky novelty into an accepted norm.

2.2 The Four Core Elements of Diffusion: A Detailed Analysis

Rogers’s framework is built upon four main elements that interact to govern the diffusion process. A comprehensive analysis of each is essential to understanding the theory’s predictive and explanatory power.

2.2.1 The Innovation

The starting point of any diffusion process is the innovation itself. Critically, Rogers defines an innovation not by its objective novelty but by its subjective perception: it is “an idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption”. This perceptual definition is paramount because it is the individual’s interpretation of the innovation, not its technical specifications, that drives their decision to adopt or reject it. The characteristics of an innovation, as perceived by members of a social system, are the primary determinants of its rate of adoption.

Characteristics of Innovations

Rogers identified five such characteristics that he argued account for between 49% and 87% of the variation in adoption rates across all categories of adopters.

-

Relative Advantage: This is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being superior to the idea, practice, or product it supersedes. The advantage is not limited to economic terms; it can manifest as increased convenience, higher social status, time savings, or improved performance. The greater the perceived relative advantage of an innovation, the more rapid its rate of adoption will be. For example, the shift from compact discs to digital music streaming offered a massive relative advantage in terms of accessibility and library size, which fueled its rapid diffusion.

-

Compatibility: This refers to the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with the existing values, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters. An innovation that aligns with established socio-cultural norms and practices faces fewer obstacles to adoption because it requires less disruptive change on the part of the individual. For instance, a new agricultural technique that is compatible with existing farming equipment and local traditions will be adopted more quickly than one that requires a complete overhaul of the farming system.

-

Complexity: This is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to understand and use. Simplicity is a key accelerator of diffusion; new ideas that are more straightforward are adopted more readily than those requiring the development of new skills and understandings. Complexity is the only one of the five attributes that is negatively related to the rate of adoption.

-

Trialability: This is the degree to which an innovation may be experimented with on a limited basis before a full commitment is required. Trialability is a powerful tool for reducing uncertainty. By allowing individuals to test an innovation, it lowers their perceived risk and allows them to learn by doing. Innovations that can be broken down into smaller, testable parts are generally adopted more rapidly than those that require an all-or-nothing decision. The prevalence of free 30-day software trials is a direct application of this principle.

-

Observability: This is the degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others. The more visible the benefits of an innovation are, the more likely it is to be adopted. High observability stimulates peer discussion and provides tangible social proof that the innovation works, which in turn reduces uncertainty for later adopters. Publicly visible technologies, such as electric scooters or smartphones, have higher observability than private innovations like new accounting software.

A related and important concept is re-invention, which refers to the degree to which an innovation is changed or modified by a user in the process of its adoption and implementation. Innovations that are flexible and can be adapted to fit the specific needs of different users are often seen as more versatile. This adaptability can increase the rate of adoption by improving the innovation’s fit with a wider range of potential adopters, effectively enhancing its compatibility and relative advantage for different user groups.

The following table provides a consolidated overview of these five critical attributes and their influence on the diffusion process.

| Attribute | Definition | Impact on Rate of Adoption | Illustrative Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Advantage | The degree to which an innovation is perceived as superior to what it replaces. | Positive (Higher advantage leads to faster adoption) | The speed and convenience of email over postal mail. |

| Compatibility | The degree to which an innovation is perceived as consistent with existing values, experiences, and needs. | Positive (Higher compatibility leads to faster adoption) | A new smartphone app that uses familiar swipe gestures. |

| Complexity | The degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to understand or use. | Negative (Higher complexity leads to slower adoption) | The steep learning curve of professional video editing software. |

| Trialability | The degree to which an innovation can be experimented with on a limited basis. | Positive (Higher trialability leads to faster adoption) | Test-driving a car before purchase or using a free software trial. |

| Observability | The degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others. | Positive (Higher observability leads to faster adoption) | The public use of wearable fitness trackers like Fitbit. |

2.2.2 Communication Channels

Innovations do not spread in a vacuum; they are communicated through channels, which are “the means by which messages get from one individual to another”. The nature of these channels has a profound impact on the diffusion process. Rogers makes a critical distinction between two main types of communication channels:

-

Mass Media Channels: These channels, such as television, radio, and newspapers (and more recently, the internet), are most effective at rapidly reaching a large audience to create knowledge and awareness about an innovation. They excel at the initial “knowledge” stage of the decision-making process.

-

Interpersonal Channels: These involve face-to-face (or mediated, person-to-person) exchanges between two or more individuals. Interpersonal channels are more effective in forming and changing attitudes toward a new idea and are therefore more influential at the “persuasion” stage of the decision process. The subjective evaluation of an innovation from a trusted peer is often the final push needed to overcome uncertainty and influence the decision to adopt or reject.

The interplay between these channels is crucial. A potential adopter might first learn about an innovation from a mass media source but will likely turn to their interpersonal network for validation before making a final decision. This dynamic is influenced by the concepts of homophily and heterophily. Homophily is the degree to which two or more individuals who interact are similar in certain attributes, such as beliefs, education, or social status. Communication is most effective when it occurs between homophilous individuals. However, for diffusion to occur, new information must be introduced into a group, which requires at least some degree of heterophily—interaction between individuals who are different. The most effective diffusion occurs when individuals are homophilous on most variables but heterophilous regarding the innovation itself (i.e., one has adopted and the other has not).

2.2.3 The Dimension of Time

Time is not merely a backdrop for diffusion; it is an integral variable in the process. Its importance is manifested in three distinct ways:

-

The Innovation-Decision Period: This is the length of time required for an individual or other decision-making unit to pass through the entire innovation-decision process, from first gaining knowledge of an innovation to either adopting or rejecting it. This period can vary significantly depending on the individual and the nature of the innovation.

-

Innovativeness of an Individual: This refers to the relative earliness or lateness with which an individual adopts a new idea compared with other members of their social system. This relative position is the basis for classifying individuals into the adopter categories discussed later.

-

Rate of Adoption: This is the relative speed with which an innovation is adopted by the members of a social system, usually measured by the number of individuals who adopt the innovation in a given time period. The rate of adoption is the ultimate dependent variable that the theory seeks to explain, and it is typically represented graphically by the S-curve.

2.2.4 The Social System

The fourth core element is the social system, which provides the context and boundaries within which diffusion occurs. A social system is defined as a set of interrelated units that are engaged in joint problem-solving to accomplish a common goal. The system’s structure, norms (established behavior patterns), and leadership dynamics can either facilitate or hinder the diffusion of innovations.

Key actors and structures within the social system include:

-

Opinion Leaders: These are individuals who are able to informally influence other individuals’ attitudes or overt behavior in a desired way with relative frequency. They are not necessarily formal leaders but are respected for their technical competence, social accessibility, and conformity to the system’s norms. Opinion leaders are critical to the diffusion process because they serve as a social model for others, and their adoption of an innovation legitimizes it for many of their peers. They exert the most influence during the evaluation stage of the decision process and on later adopters.

-

Change Agents: These are individuals who seek to influence clients’ innovation-decisions in a direction that is deemed desirable by a change agency. Unlike opinion leaders who are members of the social system, change agents are often professionals from outside the system (e.g., public health workers, agricultural extension agents, technology salespeople). Their success is positively related to the extent of their effort, their focus on clients’ needs rather than their own agency’s goals, and their ability to work through local opinion leaders.

-

Types of Innovation-Decisions: The social system’s structure also determines how adoption decisions are made. Rogers identifies three main types:

-

Optional Innovation-Decision: This decision is made by an individual independent of the decisions of other members of the system.

-

This is the most common type of decision studied in diffusion research.

- Collective Innovation-Decision: This decision is made by consensus among the members of a system. All members must conform to the group’s decision once it is made.

- Authority Innovation-Decision: This decision is made by a few individuals in positions of power or authority within a social system (e.g., an organization or government). The individual members of the system have little or no influence in the decision; they are simply expected to implement it.

2.3 The Adopter’s Journey: The Innovation-Decision Process

Diffusion is the aggregate result of many individual decisions. The innovation-decision process is the mental sequence through which an individual passes from first knowledge of an innovation to forming an attitude toward it, to a decision to adopt or reject, to implementation of the new idea, and finally to confirmation of this decision. This process is fundamentally an information-seeking and information-processing activity in which the individual is motivated to reduce uncertainty about the advantages and disadvantages of the innovation. Rogers conceptualized this journey as a series of five distinct stages. While early versions of the theory used terms like “awareness, interest, evaluation, trial, and adoption”, the model was later refined into the following five stages:

- Stage 1: Knowledge: This stage begins when an individual (or other decision-making unit) is first exposed to an innovation’s existence and gains some understanding of how it functions. At this point, the individual may have only “awareness-knowledge”—the simple fact that the innovation exists. This awareness can then motivate them to seek “how-to knowledge” (how to use it properly) and “principles-knowledge” (understanding the underlying principles of how it works). Mass media channels are particularly important at this stage for creating broad awareness.

- Stage 2: Persuasion: In the persuasion stage, the individual forms a favorable or unfavorable attitude toward the innovation. While the knowledge stage is primarily a cognitive (knowing) activity, the persuasion stage is mainly affective (feeling). The individual becomes more psychologically involved with the innovation, actively seeking information and assessing its potential based on the five perceived attributes (relative advantage, compatibility, etc.). It is at this stage that interpersonal channels and discussions with peers become critical for shaping attitudes.

- Stage 3: Decision: This stage involves the individual engaging in activities that lead to a choice to either adopt or reject the innovation. Adoption means deciding to make full use of the new idea, while rejection means deciding not to. To cope with the uncertainty that still exists, many individuals will seek to try the innovation on a partial basis if possible—a key function of trialability. A small-scale trial can provide a great deal of information and significantly reduce the perceived risk of full adoption.

- Stage 4: Implementation: During the implementation stage, the individual puts the innovation into use. Until this point, the process has been a purely mental exercise. Implementation marks the transition to overt behavior change. A degree of uncertainty about the innovation’s outcomes can still persist, and the adopter may actively seek technical assistance or information on how to use the new idea most effectively. It is also during this stage that re-invention—modifying or adapting the innovation to better suit one’s needs—is most likely to occur.

- Stage 5: Confirmation: In the final stage, the individual seeks reinforcement for the innovation-decision already made. They evaluate the results of their decision and may be exposed to conflicting messages from their peers or their own experiences. If an individual encounters messages that conflict with their decision, a state of dissonance may arise, which could lead to a later reversal of the decision. This reversal is known as discontinuance. There are two types of discontinuance: replacement discontinuance, where an idea is rejected in order to adopt a better one, and disenchantment discontinuance, where an idea is rejected as a result of dissatisfaction with its performance.

The following table provides a structured summary of this five-stage process, mapping the individual’s internal journey and the external factors that are most influential at each step.

| Stage | Primary Mental Activity | Key Questions for the Individual | Most Influential Communication Channels |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Knowledge | Cognitive (Knowing) | “What is this innovation and how does it work?” | Mass Media Channels (for awareness) |

| 2. Persuasion | Affective (Feeling) | “What are its advantages/disadvantages for me?” | Interpersonal Channels (for attitude change) |

| 3. Decision | Conative (Choosing) | “Should I try it? What are the risks?” | Peer Networks and Trial Experiences |

| 4. Implementation | Behavioral (Doing) | “How do I use this? What problems might I face?” | Technical Assistance and Change Agents |

| 5. Confirmation | Evaluative (Reinforcing) | “Was this the right decision? What are others experiencing?” | Peer Reinforcement and Personal Experience |

2.4 Mapping the Social Landscape: Adopter Categories and the S-Curve

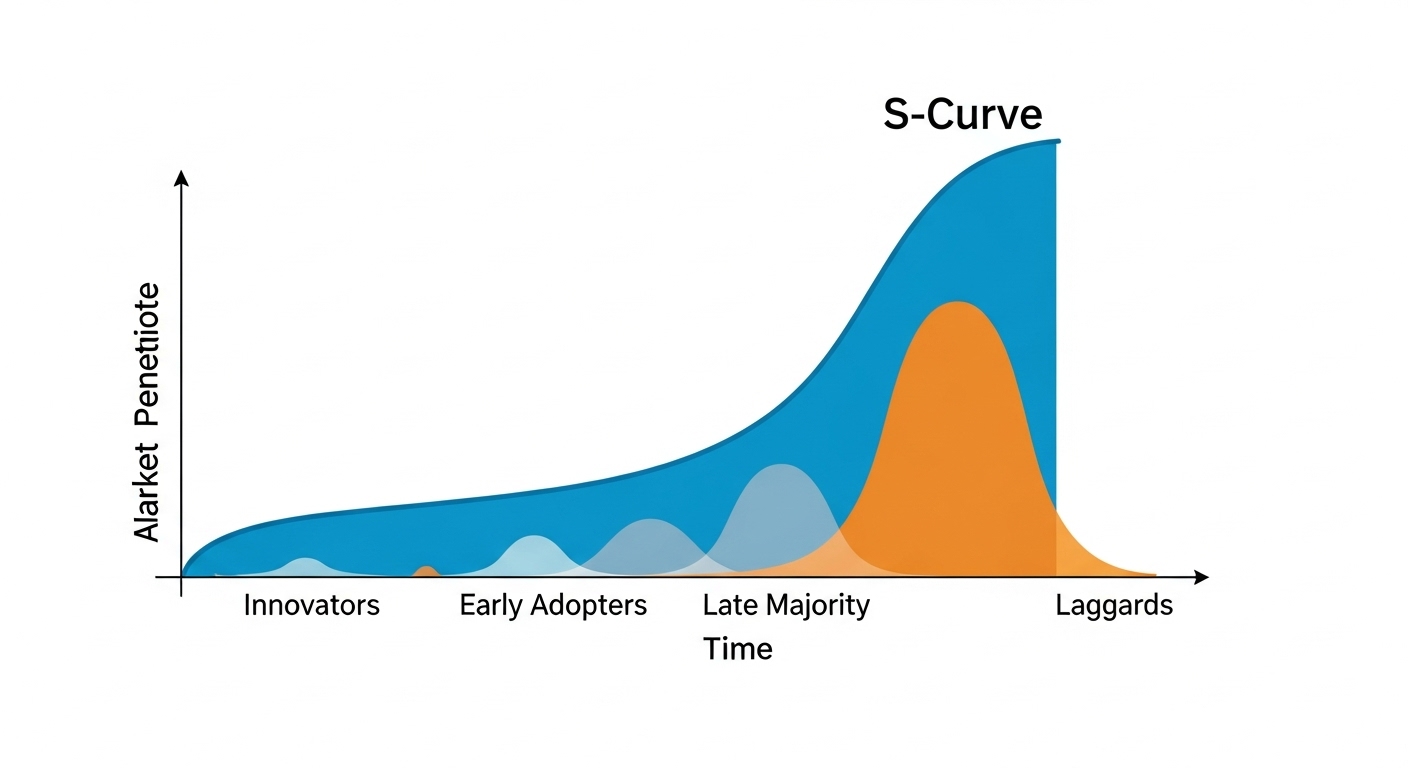

While the innovation-decision process describes the individual’s journey, diffusion theory’s broader power lies in its ability to describe and predict patterns of adoption across an entire social system. This is achieved through two of its most famous concepts: the classification of the population into adopter categories and the graphical representation of adoption over time as an S-curve.

2.4.1 The Five Adopter Categories

Innovations are not adopted by all members of a social system at the same time. Instead, individuals adopt in a time sequence, and they can be classified into categories based on their innovativeness. Rogers proposed a standardized classification system based on a normal, bell-shaped distribution, dividing the population into five segments. These categories are ideal types, designed to make it possible to compare diffusion processes across different innovations and social systems.

- Innovators (2.5%): This first group to adopt an innovation is characterized by venturesomeness and a high tolerance for risk. They are technology enthusiasts who are eager to try new ideas, often before they are fully proven. Innovators typically have the highest social status, greater financial liquidity to absorb potential losses from failed innovations, and are more cosmopolitan, with social networks that extend beyond their local community. They are the gatekeepers who bring new ideas into the social system from the outside world.

- Early Adopters (13.5%): This second group is more integrated into the local social system and represents the embodiment of successful, discrete use of new ideas. Early adopters hold the highest degree of opinion leadership in most systems. They are respected by their peers and serve as role models whose adoption decisions signal to others that an innovation is worthwhile. While they are visionaries like innovators, they are more judicious in their adoption choices, as their reputation depends on making successful ones. They are the crucial bridge between the innovators and the mainstream.

- Early Majority (34%): This group adopts new ideas just before the average member of a social system. They are deliberate and thoughtful, interacting frequently with their peers but seldom holding positions of leadership. The early majority is pragmatic; they are not interested in technology for its own sake but for the solutions and convenience it provides. Their adoption is a key indicator that an innovation has crossed into the mainstream, and their decision to adopt is what provides the momentum for the rapid acceleration phase of the S-curve.

- Late Majority (34%): This group is characterized by skepticism. They adopt new ideas just after the average member of a social system, often out of economic necessity or in response to increasing social pressure. They are cautious and will not adopt until most others in their social system have already done so, requiring the weight of system norms and strong social proof before they are convinced.

- Laggards (16%): This is the final group to adopt an innovation.

They are traditionalists whose point of reference is the past. Laggards are typically suspicious of innovations and of the change agents who promote them. They have the lowest social status and financial liquidity and are the most localite in their outlook, with their social network consisting mainly of close friends and family who share similar traditional values. By the time a laggard adopts an innovation, it may already have been superseded by a newer idea that the innovators are already using.

The following table provides a concise, comparative overview of the distinct socio-psychological profiles of each adopter segment, highlighting their role in the diffusion process.

| Adopter Category | % of Population | Key Characteristics | Role in Diffusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovators | 2.5% | Venturesome, risk-tolerant, high social status, cosmopolitan, financially liquid. | Gatekeepers; introduce new ideas into the social system. |

| Early Adopters | 13.5% | Respected opinion leaders, visionaries, well-integrated into the local social system, judicious. | Legitimizers and Role Models; crucial for bridging to the majority. |

| Early Majority | 34% | Deliberate, pragmatic, adopt just before the average, focus on solutions and convenience. | The Tipping Point; their adoption signals mainstream acceptance. |

| Late Majority | 34% | Skeptical, cautious, adopt after the average, motivated by social pressure and economic necessity. | Provide the weight of system norms; confirm the innovation is standard. |

| Laggards | 16% | Traditional, suspicious of change, past-oriented, most localite, lowest financial liquidity. | Point of reference for the past; their adoption signals full saturation. |

2.4.2 The S-Curve of Adoption

When the cumulative number of individuals who have adopted a new idea is plotted over time, the resulting distribution is an S-shaped curve. This curve is one of the most recognizable and powerful visualizations of the diffusion process. It graphically illustrates the typical pattern of adoption: a slow initial rate of adoption, followed by a period of rapid acceleration, and finally a leveling off as the innovation approaches saturation within the social system.

The shape of the S-curve is a direct result of the interaction between the adopter categories and their social networks. The initial slow ramp-up represents adoption by the innovators and early adopters. The steep acceleration in the middle of the curve occurs as the early majority and then the late majority adopt the innovation, driven by interpersonal communication and growing social proof. The curve then flattens out as only the laggards remain to adopt.

A key concept associated with the S-curve is critical mass. This is the point in the adoption process at which enough individuals in a system have adopted an innovation so that the innovation’s further rate of adoption becomes self-sustaining. This “tipping point,” which typically occurs when around 10% to 25% of the population has adopted, marks the moment when the diffusion process takes on a life of its own and no longer requires significant external effort from change agents to continue spreading.

Another important concept, particularly in technology marketing, is the chasm. Theorized as a significant gap between the early adopters (visionaries who are excited by new technology) and the early majority (pragmatists who want proven solutions), this chasm represents a major hurdle that many innovations fail to cross. Successfully navigating this transition requires a fundamental shift in marketing and product strategy to meet the very different needs of the pragmatic mainstream market.

The entire Diffusion of Innovations theory can thus be reframed as a comprehensive model for understanding how societies manage uncertainty. An innovation, by its nature, introduces uncertainty into a social system. The five perceived attributes—relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability—are the cognitive tools or heuristics that individuals use to perform a personal cost-benefit analysis and reduce this uncertainty. For example, high compatibility reduces uncertainty about social and technical disruption, while high trialability reduces uncertainty about performance and value. The five-stage decision process maps an individual’s personal journey from a state of high uncertainty (mere knowledge) to a state of resolved certainty (confirmation). Communication channels are the conduits for the uncertainty-reducing information, with trusted interpersonal channels being particularly effective at resolving the affective, or emotional, uncertainty that can be a major barrier to adoption. The S-curve, then, is the emergent, macro-level visualization of this collective uncertainty-reduction process. The slow start represents the high initial uncertainty when only risk-tolerant innovators are willing to engage. The steep climb represents a rapid decrease in social uncertainty as peer adoption provides powerful social proof. Finally, the plateau represents a state of near-certainty where the innovation has become the established, low-risk norm. This perspective elevates the theory from a simple descriptive model to a dynamic model of social epistemology—a theory of how a group of people collectively comes to “know” that a new idea is valuable and safe enough to adopt.

Part III: The Architecture of Inquiry: Mastering The Craft of Research

While Diffusion of Innovations provides a powerful lens for observing and understanding social change, The Craft of Research provides the essential toolkit for conducting the inquiry itself. It offers a systematic and rigorous methodology for constructing knowledge, transforming a researcher from a passive consumer of information into an active and persuasive contributor to a scholarly dialogue. The book’s framework is not merely a set of rules for writing but a comprehensive approach to the entire process of research, from conceptualization to final revision.

3.1 The Philosophy of the Craft: Research as a Social Conversation

The foundational premise of The Craft of Research is a reconceptualization of the research act itself. It posits that research is not a solitary journey into a library or laboratory to uncover facts, but rather a profoundly social activity—a dynamic “conversation” with a community of readers and fellow researchers, both past and present. Every research project is an entry into an ongoing dialogue. This perspective fundamentally shifts the researcher’s task from simply reporting information to engaging in a persuasive and collaborative effort to build shared understanding.

This conversational model requires the researcher to be constantly mindful of their audience. They must consciously create a role for themselves (e.g., as a problem-solver, a synthesizer of new information) and simultaneously imagine the role of their readers, anticipating their existing knowledge, their interests, their values, and, most importantly, their potential questions and objections. The ultimate goal is not just to present a claim but to motivate readers to accept that claim and to understand its significance within the broader scholarly conversation. This reader-centric approach is the guiding principle that informs every stage of the research process described in the book.

3.2 Framing the Inquiry: From Vague Interest to Significant Problem

The book provides a clear, iterative process for moving from a nascent idea to a well-defined research project that is worth pursuing for both the researcher and their audience.

- Step 1: From Interest to Topic: All research begins with an interest, but a general interest is too broad to be the subject of a focused project. The first step is to narrow this interest into a manageable and specific topic. This often involves preliminary reading and exploration to understand the contours of a subject area and identify a plausible niche.

- Step 2: From Topic to Questions: A topic alone is not enough; it is merely a subject. To give the research direction and purpose, the topic must be interrogated to generate genuine, productive research questions. These are not simple “look-up” questions that can be answered with a single fact, but rather analytical or interpretive questions that require the researcher to synthesize information and develop an argument.

- Step 3: From Questions to a Problem: The most critical step in framing the inquiry is to elevate a research question into a research problem. A research problem is formulated by identifying a gap, a contradiction, or an area of incomplete understanding within the existing scholarly conversation. The book distinguishes between a practical problem (a condition in the world that needs to be changed) and a conceptual problem (a condition of incomplete knowledge or flawed understanding that needs to be resolved). Academic research primarily addresses conceptual problems. The solution to a research problem is not just an answer to a question, but a contribution that helps the entire research community understand something more clearly or accurately.

- The “So What?” Question: To ensure the research is meaningful, the authors insist that every researcher must be able to answer the most demanding question a reader can ask: “So what?”. The researcher must articulate the significance of their problem—the costs of not solving it and the benefits of solving it. Answering the “So what?” question establishes the relevance and importance of the research, providing the motivation for readers to engage with the work.

3.3 Constructing the Argument: The Five Pillars of Persuasion

The heart of The Craft of Research is its robust and detailed framework for building a persuasive research argument.

This framework is not a rigid formula but a flexible structure composed of five essential, interconnected elements that work together to create a sound and compelling case.

3.3.1 Claim

The claim is the central assertion, the main point, or the conclusion of the argument. It is the answer to the primary research question. To be effective, a claim must be both substantive (important enough to warrant consideration) and contestable (not a statement of fact but an assertion that others might reasonably challenge). It must also be stated with specificity and clarity, avoiding vague language.

3.3.2 Reasons

Reasons are the statements that provide the logical support for the claim. They answer the reader’s implicit question, “Why should I believe your claim?” Reasons are typically linked to the claim by the word “because” and form the main sections or sub-arguments of a research paper. A strong argument is built upon a foundation of clear and logical reasons.

3.3.3 Evidence

Evidence is the bedrock of a research argument. It consists of the data, facts, quotations, examples, or other sources that are used to support the reasons. Reasons are assertions made by the researcher; evidence is the verifiable information that makes those assertions credible. The authors stress that evidence must be evaluated for its reliability, sufficiency, representativeness, and accuracy. It is also crucial for researchers to distinguish between the evidence itself and mere reports of evidence, as the act of reporting can shape and interpret the raw data.

3.3.4 Acknowledgment and Response

A sophisticated argument does more than just present its own case; it anticipates and engages with the views of its readers. The process of acknowledgment and response involves identifying potential questions, objections, counterarguments, or alternative interpretations and addressing them directly in the text. This demonstrates the researcher’s thoroughness and fairness, thereby building their credibility, or ethos, with the reader. By thoughtfully responding to potential challenges, the researcher strengthens their own argument and shows respect for the complexity of the issue and the intelligence of their audience.

3.3.5 Warrant

The warrant is arguably the most complex but most crucial element of the argument. It is the underlying principle, assumption, or general rule that connects a particular reason to a particular claim. It answers the reader’s skeptical question, “How does your reason logically lead to your claim?” or “What’s the connection?”. Warrants are often unstated because they are assumed to be part of the shared understanding within a specific research community. However, making warrants explicit is essential when addressing a diverse audience, when the logic is novel or controversial, or when the connection between a reason and a claim might not be immediately obvious. A sound argument requires not only valid reasons and evidence but also a strong and appropriate warrant to justify the logical leap from one to the other.

This entire framework is more than just a template for organizing a paper; it is a powerful cognitive tool for critical thinking. A novice researcher might begin with a topic, collect a large amount of information, and then attempt to assemble it into a coherent paper—a bottom-up process that often results in a “data dump” rather than an argument. The framework from The Craft of Research inverts this process. It encourages a top-down approach where the researcher begins by formulating a tentative claim (a hypothesis). This immediately provides direction and focus for the research. To support this claim, the researcher must then actively seek out logical reasons, which structures the inquiry into clear sub-topics. For each reason, the researcher must then find specific, targeted evidence, making the data collection process far more efficient. Most importantly, the framework forces the researcher to constantly evaluate the warrant that connects their reasons to their claim. For example, a researcher might have the reason, “Interviewee A stated a strong preference for product X,” and the claim, “Therefore, the target market prefers product X.” The framework forces the researcher to confront the weak underlying warrant: “The opinion of one individual is representative of an entire market.” Recognizing this logical flaw early in the process prompts the researcher to either gather more representative evidence or to qualify and narrow their claim. In this way, the framework transforms the research process from a passive aggregation of facts into an active, rigorous testing of a logical structure. It is a tool for thinking, not just for presenting.

The following table provides a definitive, at-a-glance reference for this logical structure, deconstructing the framework into its core components and their functions.

| Component | Definition | Function in the Argument | Key Question it Answers for the Reader |

|---|---|---|---|

| Claim | The central, contestable assertion or conclusion of the research. | To state the main point or thesis of the argument. | “What is your point?” |

| Reason | A statement that provides logical support for the claim. | To explain why the claim should be accepted; to structure the argument. | “Why should I believe you?” |

| Evidence | The verifiable data, facts, or sources that support the reasons. | To ground the reasons in credible, factual information. | “How do you know that?” or “Can you prove it?” |

| Acknowledgment & Response | The anticipation and addressing of alternative views, questions, or objections. | To demonstrate thoughtfulness, build credibility (ethos), and strengthen the argument. | “But what about…?” or “Have you considered…?” |

| Warrant | The underlying principle or assumption that connects a reason to a claim. | To provide the logical bridge that justifies the inference from reason to claim. | “How does your reason support your claim?” or “So what’s the connection?” |

3.4 Executing the Craft: A Cyclical Process of Drafting and Revision

A key insight from The Craft of Research is that the research and writing process is not linear but cyclical and recursive. Experienced researchers rarely move in a straight line from question to outline to final draft. Instead, they loop back and forth, allowing the act of drafting to reveal problems in an argument, which in turn prompts further research or a rethinking of the initial claim.

- Planning and Drafting: The book advises against common but flawed organizational plans, such as structuring a paper around the chronological story of one’s research or simply summarizing sources one by one. Instead, the plan should be built around the logical structure of the argument itself: the claim and its supporting reasons. The drafting process then becomes an exercise in fleshing out this logical skeleton.

- Revision: Revision is presented not as a final step of polishing and proofreading but as the core of the writing process. It is the act of “re-seeing” the draft through the eyes of a reader. This involves revising on multiple levels: checking the global organization of the argument, strengthening the claims and evidence, clarifying the logic, and improving the style of individual sentences and paragraphs to ensure clarity and impact.

- Introductions and Conclusions: The book provides a powerful template for introductions, which should accomplish three tasks: establish common ground with the reader, state the problem (the gap in knowledge or understanding), and present the claim or response that solves the problem. Conclusions should do more than simply summarize; they should restate the main point in a new light and, most importantly, reflect on its broader significance, once again answering the “So what?” question.

- Ethics: Woven throughout the process is a deep commitment to the ethics of research. This includes the obvious prohibitions against plagiarism and data fabrication but extends to a broader set of intellectual virtues: reporting evidence fairly, acknowledging the work of others accurately, representing opposing views without distortion, and accepting the shared responsibility of contributing to a trustworthy body of knowledge.

Part IV: Synthesis and Application: A Unified Framework for Analysis

By integrating the macro-social perspective of Diffusion of Innovations with the micro-methodological rigor of The Craft of Research, a unified and powerful framework for analysis emerges. This synthesis allows a researcher not only to understand the complex dynamics of how ideas spread but also to investigate and communicate those dynamics with precision and persuasive force. Furthermore, it provides a reflexive lens through which researchers can understand their own role and the fate of their work within the academic ecosystem.

4.1 Applying the Craft to Diffusion: A Methodological Blueprint

To illustrate the practical synergy between the two books, consider a hypothetical research scenario: investigating the surprisingly slow diffusion of a new, evidence-based educational technology within a large school district.

The framework from The Craft of Research provides a step-by-step blueprint for structuring this investigation, while the concepts from Diffusion of Innovations provide the theoretical vocabulary and analytical tools.

Step 1: From Topic to Problem

The researcher moves from a broad interest in “educational technology” (the topic) to a focused inquiry: “Why has the district’s new ‘SmartRead’ literacy software, despite positive external reviews and significant investment, seen only 15% teacher adoption after its first year?” (the question). This question is then framed as a research problem with clear significance: “This low adoption rate represents a failure to capitalize on a substantial financial investment and, more importantly, a missed opportunity to improve student literacy outcomes. Understanding the barriers to its diffusion is a problem of both practical consequence for the district and conceptual significance for the field of educational technology implementation”. The “So what?” is explicitly defined by the wasted resources and the potential harm to student learning.

Step 2: Constructing the Argument using Diffusion Concepts

The researcher can now build a formal argument using the five-pillar structure, populating it with concepts from Rogers’s theory.

Claim: The slow diffusion of SmartRead is primarily attributable to its high perceived complexity and its incompatibility with established teaching workflows, which have negated its perceived relative advantage.

Reasons: Teachers perceive the software as overly complex because they have not received adequate, hands-on training. The software’s rigid, data-entry-heavy structure is incompatible with the dynamic and flexible lesson planning habits valued by experienced educators.

Evidence: To support these reasons, the researcher would gather targeted evidence: survey data measuring teacher perceptions of all five of Rogers’s innovation attributes; interview transcripts with innovators, early adopters, and a large sample of the early majority (the non-adopters); usage logs from the software platform to quantify adoption rates; and a content analysis of the district’s training materials to assess their quality and thoroughness.

Warrant: The argument rests on a central warrant drawn directly from diffusion theory: in the adoption of new technologies, subjectively perceived attributes like complexity and compatibility are often more powerful determinants of behavior than objective measures of the technology’s benefits.

Acknowledgment and Response: The researcher must anticipate the common alternative explanation: that the teachers are simply laggards who are “resistant to change”. They can respond to this objection with evidence showing that this same group of teachers has readily adopted other, simpler innovations in recent years (e.g., a new grading portal). This response effectively isolates the cause of the problem to the attributes of the specific innovation, not the inherent characteristics of the adopters, thereby strengthening the original claim.

This example demonstrates how The Craft of Research provides the logical architecture for the investigation, while Diffusion of Innovations provides the specialized theoretical content needed to build a meaningful and insightful analysis.

4.2 The Diffusion of Research Itself: Academia as a Social System

The synthesis becomes even more profound when Rogers’s theory is applied reflexively to the very process of academic research. The academic world, with its distinct disciplines, invisible colleges, and pecking orders, is a perfect example of a social system through which new ideas—research findings, theories, methodologies—diffuse.

Academic Paradigms as Innovations

A groundbreaking new theory, a novel research methodology, or a startling empirical finding can be understood as an “innovation” that must diffuse through the “social system” of its academic field. Its adoption is not guaranteed by its intellectual merit alone; it is subject to the same social dynamics that govern the spread of hybrid corn or new medicines.

Mapping Diffusion Concepts onto Academia

-

Adopter Categories: The academic community can be segmented just like any other population. The innovators are the scholars who create the new paradigm. The early adopters are often prominent, well-respected figures in the field who champion the new idea, giving it legitimacy. The early majority consists of the graduate students and junior faculty who begin to use the theory in their own work, teach it in their courses, and cite it, pushing it into the mainstream. The late majority are established scholars who adopt the idea only after it has become a standard part of the disciplinary canon. And the laggards are those who cling to older paradigms, often resisting the new idea for their entire careers.

-

Innovation Attributes: The success of a new academic idea depends on its perceived attributes. Its relative advantage is its explanatory power over existing theories. Its compatibility is how well it aligns with or builds upon the established knowledge and methodological norms of the discipline. Its complexity is its intellectual difficulty and the steepness of the learning curve required to master it. Its trialability is the ease with which it can be applied to a small-scale research project to test its utility. Its observability is the visible success and prestige of the scholars who adopt it, measured in publications in top-tier journals, major grants, and prominent conference presentations.

-

Communication Channels: Formal channels like peer-reviewed journals and academic conferences serve as the primary mass media for creating awareness. However, the crucial work of persuasion happens through interpersonal channels: mentor-student relationships, co-authorship networks, scholarly societies, and the informal “invisible colleges” of researchers who share and critique each other’s work before publication.

-

The S-Curve: The rise of a new academic paradigm—from behavioral economics to post-structuralism—often follows a classic S-curve, which can be tracked through citation counts, appearances in course syllabi, and the number of dissertations based on the new framework.

4.3 The Researcher as Strategic Change Agent

This synthesis culminates in a new, more complete portrait of the modern researcher. The researcher is not merely a dispassionate observer of diffusion, nor are they solely a logical constructor of arguments. They are, in fact, an active participant in a diffusion process and can be understood as a strategic change agent seeking to promote the adoption of their own intellectual “innovations”.

By mastering the principles of The Craft of Research, a scholar learns how to design and package their innovation—their research findings—to maximize its positive perceived attributes. A clearly written, well-organized, and logically sound paper reduces its perceived complexity. A thorough literature review that explicitly connects the new findings to existing scholarly conversations increases its compatibility. A study with a robust methodology and unambiguous results enhances its observability and demonstrates its relative advantage.

Simultaneously, by understanding the principles of Diffusion of Innovations, the researcher gains a strategic map of their academic landscape. They can identify the opinion leaders in their field whose endorsement would be most valuable. They can choose the most appropriate communication channels—the right journals, the right conferences—to reach their target audience. They can understand the social norms and network structures that will govern the reception and potential adoption of their work.

There is, however, a fundamental tension that the successful researcher must navigate. The Craft of Research operates on the assumption of a rational reader who can be persuaded by a logically sound argument built on evidence and valid warrants. It represents an idealized model of intellectual discourse.

Diffusion of Innovations, on the other hand, reveals that real-world adoption decisions are heavily influenced by social pressures, peer behavior, subjective perceptions, and other factors that are not purely rational. The early majority often adopts not because they have rigorously analyzed the innovation’s merits, but because the respected early adopters have, a powerful heuristic of social proof. This creates a critical paradox for the academic researcher. A logically perfect paper, the epitome of the Craft, may fail to diffuse if it is not “compatible” with the prevailing norms of the field, if its ideas are too “complex,” or if it is not championed by influential “opinion leaders.” Conversely, a flawed or less rigorous idea might diffuse rapidly if it offers a high “relative advantage” in the form of a simple, elegant theory that appears to explain a great deal, and if it is promoted effectively through the right social networks.

Conclusion

The ultimate conclusion of this synthesis is that sustained academic impact requires a dual mastery. The researcher must possess the intellectual rigor to construct a logically sound and evidence-based argument, as prescribed by The Craft of Research. But they must also possess the social and strategic intelligence to navigate the complex, often non-rational, diffusion process described by Diffusion of Innovations. One skill set without the other is insufficient. The ability to craft a perfect argument is of little use if that argument is never read or adopted. The ability to market an idea is intellectually hollow if the idea itself lacks substance and rigor.

The truly effective researcher, therefore, is one who can operate in both domains, seamlessly integrating the craft of inquiry with an understanding of the dynamics of social change. They are architects of knowledge who also understand the social physics of its dissemination. By bringing these two foundational texts into a single, unified framework, we equip the researcher not only to produce knowledge of the highest quality but also to ensure that knowledge has a meaningful and lasting impact on the world.

📚 For more insights, check out our comprehensive SEO guide.