Marxism, Leninism, Maoism: Communist Ideologies Compared

I. Introduction: Deconstructing “Communism”

A. Clarifying the Terminological Complex

The term “communism” is frequently employed as a monolithic descriptor, obscuring a vast and deeply factionalized landscape of political theory and state practice. A rigorous analysis, as requested, necessitates a precise deconstruction of the terminology.

First, a distinction must be drawn between the method, the ideology, and the goal. Marxism is primarily a philosophical, economic, and historical-analytic method developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, rooted in concepts like historical materialism and class struggle. The communist goal is twofold: 1) a “lower-stage of communism,” (often called socialism) which is the transitional society following a revolution, characterized by the “dictatorship of the proletariat” and potentially retaining elements like money and a state; and 2) a “higher-stage of communism,” the final, utopian vision of a “classless” and “stateless” society.

The query’s “Leninist Marxist” is interpreted as Marxism-Leninism. This is a specific state-sanctioned ideology developed after Vladimir Lenin’s death, primarily by Joseph Stalin in the 1920s. It codified Lenin’s strategic and organizational adaptations of Marx into a rigid doctrine for governing one-party states. Maoism, in turn, is an adaptation and development of Marxism-Leninism, formulated to address the material conditions of a semi-feudal, agrarian society.

B. The Genealogical Approach: Ideology as Adaptation

This report proceeds not as a flat comparison but as a genealogical analysis, tracing the “tree” of communist thought. We begin with the common ancestor, Classical Marxism, which was formulated in the context of 19th-century industrial Europe. We then analyze how subsequent major ideologies—namely Marxism-Leninism and Maoism—”diverged” by adapting this core theory to vastly different material conditions. These adaptations were necessary as the revolutionary locus shifted from industrial Germany and Britain to the tsarist autocracy of Russia and, later, to the semi-feudal, agrarian landscape of mid-20th-century China.

C. Core Thematic Insight: The Dialectic of Determinism vs. Voluntarism

The primary “difference” between these ideologies is their attempt to resolve the core tension in Marx’s own work: the conflict between historical determinism and revolutionary voluntarism.

On one hand, Marx’s theory of historical materialism is deterministic. It posits that history progresses through inevitable stages (modes of production). Capitalism, therefore, must first mature and then collapse from its own internal contradictions, such as the falling rate of profit. This implies that revolution would occur in the most advanced industrial nations, like Britain or Germany.

On the other hand, Marx’s political writings, particularly The Communist Manifesto, are a work of revolutionary voluntarism—a call to consciously and willfully overthrow the existing order (“forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions”).

This created a historical problem: the deterministic prediction failed. Revolution did not occur in the advanced West. Instead, it erupted in “backward” societies like Russia and China, which were autocratic, semi-feudal, and agrarian—the opposite of what Marx’s deterministic model predicted.

Leninism and Maoism are, fundamentally, voluntarist ideologies. They are theories of action designed to force the revolution to happen in conditions that Marx did not foresee. Their “differences” lie in how they justify this voluntarism and what tools (the Party, the peasantry, the Red Army) they develop to achieve it.

II. The Foundation: Classical Marxism (Marx and Engels)

A. Historical Materialism: The Base and Superstructure

The philosophical foundation of Classical Marxism is Historical Materialism. This theory posits that society is fundamentally determined by its material conditions—the mode of production used to fulfill basic human needs.

This mode of production is divided into two parts:

- The Economic Base (Base): This consists of the “forces of production” (technology, raw materials, labor power) and the “relations of production” (the class structure and property relations, such as the relationship between lord and serf, or bourgeoisie and proletariat).

- The Societal Superstructure (Superstructure): The economic base gives rise to and determines the superstructure, which includes the state, legal systems, politics, religion, art, and culture.

Marx saw history as a progression of these modes of production, each defined by its own class conflict: from primitive communism to ancient slave society, to feudalism, to the contemporary mode of capitalism. He predicted this process would inevitably lead to a future communist society.

B. The Engine of History: Class Struggle (Bourgeoisie vs. Proletariat)

According to Marx and Engels, “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. This class struggle is the “engine” of historical change.

In the capitalist epoch, society is simplified into two “great hostile camps” :

- The Bourgeoisie: The “modern capitalists,” defined as the owners of the “means of social production” (factories, land, machinery) and the employers of wage labor.

- The Proletariat: The “modern wage labourers,” defined by their lack of ownership of the means of production. They are “reduced to selling their labour power in order to live”.

This antagonistic relationship, wherein the bourgeoisie extracts “surplus value” from the proletariat’s labor, is the central dialectic (or conflict) that Marx believed would intensify until it led to capitalism’s inevitable collapse and a proletarian revolution. Other classes, such as the peasantry or landlords, were seen as residual forces from feudalism, incapable of organizing and effecting systemic change.

C. The Revolutionary Transition: The “Dictatorship of the Proletariat”

One of the most critical and contested concepts in Marxism is the “dictatorship of the proletariat” (DoP). Marx most famously articulated this in his 1875 Critique of the Gotha Programme.

- Definition: For Marx and Engels, the term DoP was synonymous with the “rule of the proletariat” or a “workers’ state”. It did not imply a dictatorship by an individual or a small cabal. Rather, it referred to a class dictatorship—the organized political rule of the entire working-class majority. This was posed in contrast to bourgeois democracy, which Marxists view as a “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie,” where the state apparatus is wielded by the capitalist class to protect its interests.

- Purpose (Transitional State): The DoP is not the final goal. It is the “necessary transit point” and the “political transition period” between capitalism and higher-stage communism. Its purpose is to use state power to dismantle the old bourgeois structures, suppress counter-revolution from the defeated bourgeoisie, and build the new socialist (lower-stage communist) society.

- The “Withering Away”: The ultimate aim of the DoP is the abolition of all classes. Marx argued that once classes no longer exist, the state—as an instrument of one class’s rule over another—becomes obsolete. It therefore “becomes extinct” or “withers away”.

This concept, however, contained a profound ambiguity that became the central fissure of 20th-century communism. While Marx was specific that a DoP must exist, he was vague on its precise form. His only concrete example was the Paris Commune, a multi-partied, decentralized, and democratic council system. This left a critical question unanswered: Does “rule of the proletariat” mean the entire class rules directly, through democratic councils? Or can it mean “rule by a party that represents the proletariat’s ‘true’ interests”?.

Facing the realities of an autocratic state and a failed revolution in 1905, Vladimir Lenin seized upon the second interpretation. His innovation of the Vanguard Party would be the instrument that wields the DoP. This interpretation—the identification of the Party with the State, and the State with the Proletariat—is the foundational assumption that led to the 20th-century one-party state. Every subsequent split, from Trotskyism to Maoism to Luxemburgism, is, in essence, a different response to this fundamental Leninist “solution” to Marx’s ambiguity.

III. The Leninist Adaptation: Marxism-Leninism as Theory and Practice

A. The Global Context: Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism

Lenin’s Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism is his grand-strategic justification for revolution in a “backward” country. He argued that 19th-century competitive capitalism had mutated into a new, global stage defined by five features :

- The concentration of production has created Monopolies.

- The merging of bank and industrial capital has created Finance Capital and a “financial oligarchy”.

- The Export of Capital (investing in other countries), as distinguished from the export of commodities, becomes paramount.

- The formation of international monopolist associations (cartels) to divide the world.

- The territorial division of the entire world among the biggest capitalist powers is complete.

From this, Lenin derived the concept of the “Labor Aristocracy.” He argued that the “super-profits” extracted from the colonial exploitation of the “Third World” were used by capitalists to bribe an “upper stratum of the working class” (e.g., skilled union leaders) in the imperialist heartlands.

This theory accomplished two goals. First, it explained why Marx’s prediction of revolution in the West had failed: the Western proletariat had become reformist and “opportunist” because it was complicit in, and benefiting from, imperial exploitation. Second, it shifted the revolutionary locus. Capitalism was now a global system.

I. Introduction: Deconstructing “Communism”

A. Clarifying the Terminological Complex

The term “communism” is frequently employed as a monolithic descriptor, obscuring a vast and deeply factionalized landscape of political theory and state practice. A rigorous analysis, as requested, necessitates a precise deconstruction of the terminology.

First, a distinction must be drawn between the method, the ideology, and the goal. Marxism is primarily a philosophical, economic, and historical-analytic method developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, rooted in concepts like historical materialism and class struggle. The communist goal is twofold: 1) a “lower-stage of communism,” (often called socialism) which is the transitional society following a revolution, characterized by the “dictatorship of the proletariat” and potentially retaining elements like money and a state; and 2) a “higher-stage of communism,” the final, utopian vision of a “classless” and “stateless” society.

The query’s “Leninist Marxist” is interpreted as Marxism-Leninism. This is a specific state-sanctioned ideology developed after Vladimir Lenin’s death, primarily by Joseph Stalin in the 1920s. It codified Lenin’s strategic and organizational adaptations of Marx into a rigid doctrine for governing one-party states. Maoism, in turn, is an adaptation and development of Marxism-Leninism, formulated to address the material conditions of a semi-feudal, agrarian society.

B. The Genealogical Approach: Ideology as Adaptation

This report proceeds not as a flat comparison but as a genealogical analysis, tracing the “tree” of communist thought. We begin with the common ancestor, Classical Marxism, which was formulated in the context of 19th-century industrial Europe. We then analyze how subsequent major ideologies—namely Marxism-Leninism and Maoism—”diverged” by adapting this core theory to vastly different material conditions. These adaptations were necessary as the revolutionary locus shifted from industrial Germany and Britain to the tsarist autocracy of Russia and, later, to the semi-feudal, agrarian landscape of mid-20th-century China.

C. Core Thematic Insight: The Dialectic of Determinism vs. Voluntarism

The primary “difference” between these ideologies is their attempt to resolve the core tension in Marx’s own work: the conflict between historical determinism and revolutionary voluntarism.

On one hand, Marx’s theory of historical materialism is deterministic. It posits that history progresses through inevitable stages (modes of production). Capitalism, therefore, must first mature and then collapse from its own internal contradictions, such as the falling rate of profit. This implies that revolution would occur in the most advanced industrial nations, like Britain or Germany.

On the other hand, Marx’s political writings, particularly The Communist Manifesto, are a work of revolutionary voluntarism—a call to consciously and willfully overthrow the existing order (“forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions”).

This created a historical problem: the deterministic prediction failed. Revolution did not occur in the advanced West. Instead, it erupted in “backward” societies like Russia and China, which were autocratic, semi-feudal, and agrarian—the opposite of what Marx’s deterministic model predicted.

Leninism and Maoism are, fundamentally, voluntarist ideologies. They are theories of action designed to force the revolution to happen in conditions that Marx did not foresee. Their “differences” lie in how they justify this voluntarism and what tools (the Party, the peasantry, the Red Army) they develop to achieve it.

II. The Foundation: Classical Marxism (Marx and Engels)

A. Historical Materialism: The Base and Superstructure

The philosophical foundation of Classical Marxism is Historical Materialism. This theory posits that society is fundamentally determined by its material conditions—the mode of production used to fulfill basic human needs.

This mode of production is divided into two parts:

- The Economic Base (Base): This consists of the “forces of production” (technology, raw materials, labor power) and the “relations of production” (the class structure and property relations, such as the relationship between lord and serf, or bourgeoisie and proletariat).

- The Societal Superstructure (Superstructure): The economic base gives rise to and determines the superstructure, which includes the state, legal systems, politics, religion, art, and culture.

Marx saw history as a progression of these modes of production, each defined by its own class conflict: from primitive communism to ancient slave society, to feudalism, to the contemporary mode of capitalism. He predicted this process would inevitably lead to a future communist society.

B. The Engine of History: Class Struggle (Bourgeoisie vs. Proletariat)

According to Marx and Engels, “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. This class struggle is the “engine” of historical change.

In the capitalist epoch, society is simplified into two “great hostile camps” :

- The Bourgeoisie: The “modern capitalists,” defined as the owners of the “means of social production” (factories, land, machinery) and the employers of wage labor.

- The Proletariat: The “modern wage labourers,” defined by their lack of ownership of the means of production. They are “reduced to selling their labour power in order to live”.

This antagonistic relationship, wherein the bourgeoisie extracts “surplus value” from the proletariat’s labor, is the central dialectic (or conflict) that Marx believed would intensify until it led to capitalism’s inevitable collapse and a proletarian revolution. Other classes, such as the peasantry or landlords, were seen as residual forces from feudalism, incapable of organizing and effecting systemic change.

C. The Revolutionary Transition: The “Dictatorship of the Proletariat”

One of the most critical and contested concepts in Marxism is the “dictatorship of the proletariat” (DoP). Marx most famously articulated this in his 1875 Critique of the Gotha Programme.

- Definition: For Marx and Engels, the term DoP was synonymous with the “rule of the proletariat” or a “workers’ state”. It did not imply a dictatorship by an individual or a small cabal. Rather, it referred to a class dictatorship—the organized political rule of the entire working-class majority. This was posed in contrast to bourgeois democracy, which Marxists view as a “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie,” where the state apparatus is wielded by the capitalist class to protect its interests.

- Purpose (Transitional State): The DoP is not the final goal. It is the “necessary transit point” and the “political transition period” between capitalism and higher-stage communism. Its purpose is to use state power to dismantle the old bourgeois structures, suppress counter-revolution from the defeated bourgeoisie, and build the new socialist (lower-stage communist) society.

- The “Withering Away”: The ultimate aim of the DoP is the abolition of all classes. Marx argued that once classes no longer exist, the state—as an instrument of one class’s rule over another—becomes obsolete. It therefore “becomes extinct” or “withers away”.

This concept, however, contained a profound ambiguity that became the central fissure of 20th-century communism. While Marx was specific that a DoP must exist, he was vague on its precise form. His only concrete example was the Paris Commune, a multi-partied, decentralized, and democratic council system. This left a critical question unanswered: Does “rule of the proletariat” mean the entire class rules directly, through democratic councils? Or can it mean “rule by a party that represents the proletariat’s ‘true’ interests”?.

Facing the realities of an autocratic state and a failed revolution in 1905, Vladimir Lenin seized upon the second interpretation. His innovation of the Vanguard Party would be the instrument that wields the DoP. This interpretation—the identification of the Party with the State, and the State with the Proletariat—is the foundational assumption that led to the 20th-century one-party state. Every subsequent split, from Trotskyism to Maoism to Luxemburgism, is, in essence, a different response to this fundamental Leninist “solution” to Marx’s ambiguity.

III. The Leninist Adaptation: Marxism-Leninism as Theory and Practice

A. The Global Context: Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism

Lenin’s Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism is his grand-strategic justification for revolution in a “backward” country. He argued that 19th-century competitive capitalism had mutated into a new, global stage defined by five features :

- The concentration of production has created Monopolies.

- The merging of bank and industrial capital has created Finance Capital and a “financial oligarchy”.

- The Export of Capital (investing in other countries), as distinguished from the export of commodities, becomes paramount.

- The formation of international monopolist associations (cartels) to divide the world.

- The territorial division of the entire world among the biggest capitalist powers is complete.

From this, Lenin derived the concept of the “Labor Aristocracy.” He argued that the “super-profits” extracted from the colonial exploitation of the “Third World” were used by capitalists to bribe an “upper stratum of the working class” (e.g., skilled union leaders) in the imperialist heartlands.

This theory accomplished two goals. First, it explained why Marx’s prediction of revolution in the West had failed: the Western proletariat had become reformist and “opportunist” because it was complicit in, and benefiting from, imperial exploitation. Second, it shifted the revolutionary locus. Capitalism was now a global system.

Revolution would therefore not begin at the core, but at the “weakest link” in the imperialist chain—a less-developed, heavily exploited nation like Russia, where class contradictions were most acute. This theory validated the Russian Revolution within a global Marxist framework.

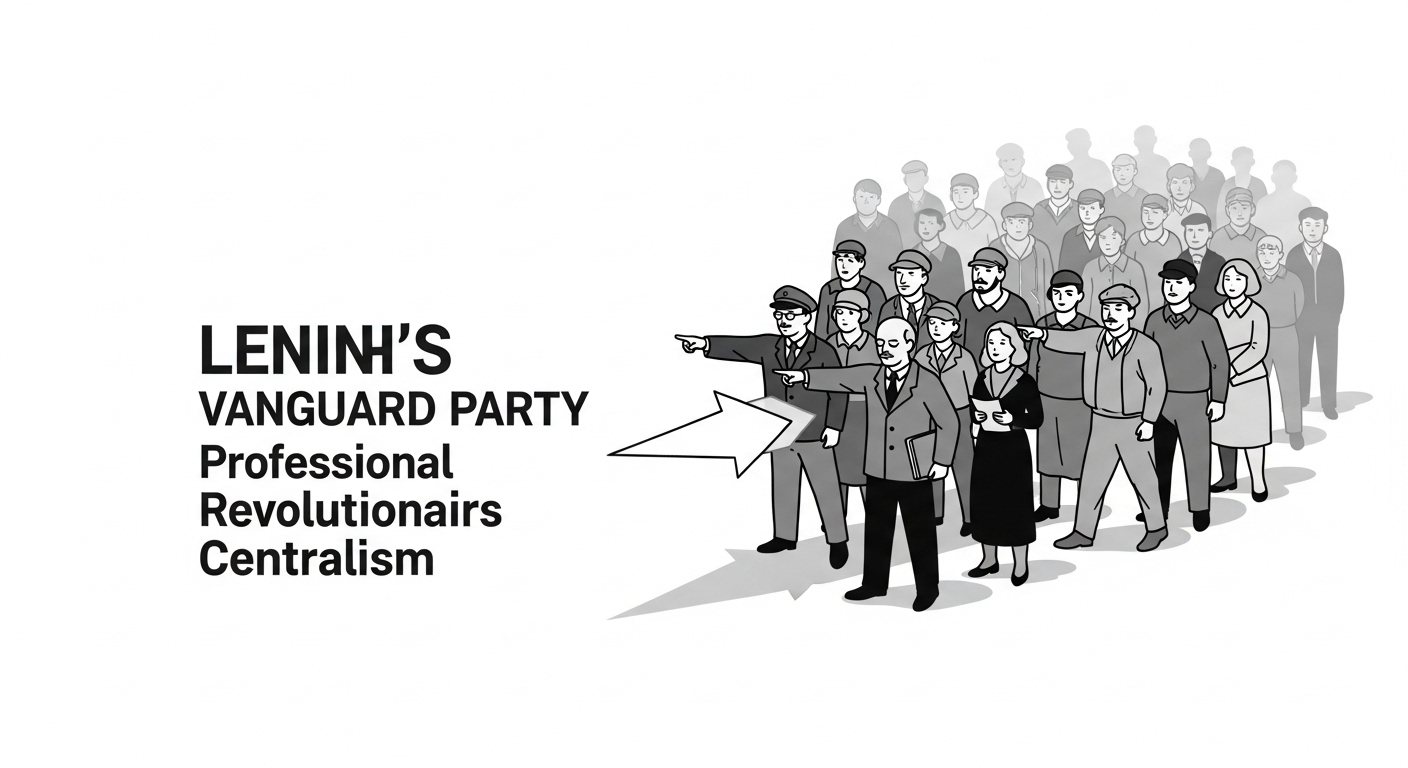

B. The Instrument of Revolution: The Vanguard Party and Democratic Centralism

If revolution was to happen in autocratic Russia, an instrument was needed to will it into existence. This instrument, outlined in Lenin’s What Is to be Done?, was the Vanguard Party.

- The Vanguard Party: Lenin was pessimistic about the “spontaneous” development of revolutionary consciousness. He argued that workers, left to their own devices, would only develop “trade-union consciousness” (seeking better wages and reforms, not revolution). Therefore, a Vanguard Party of “professional revolutionaries“, composed of the most “conscious and disciplined workers” and intellectuals, was necessary. The Party’s role is to bring Marxist theory to the proletariat from the outside and act as the “solely qualified” leader of the revolution. This Party is the instrument for establishing and exercising the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.

- Democratic Centralism: This is the organizational principle of the Vanguard Party. It purports to combine two opposing forms of leadership:

- Democracy: “Free and open discussion” and debate is encouraged before a decision is made.

- Centralism: Once a vote is taken, all discussion must end. The decision of the majority becomes the “party line,” which is binding on all members with “extreme discipline“.

This principle was formally adopted at the 10th Party Congress in 1921 in Lenin’s resolution “On Party Unity,” which banned factions, arguing they would prevent the party from acting effectively. In practice, this fusion of ideas (the Vanguard Party as the DoP, organized by Democratic Centralism) created a substitution: the Party, a minority of the class, became the de facto “dictator” on behalf of the class. This fusion of Party and State is the kernel of the 20th-century communist state and the primary target of all subsequent anti-Leninist critique.

C. The Stalinist Codification: “Marxism-Leninism” and “Socialism in One Country”

After Lenin’s death in 1924, Joseph Stalin consolidated power and codified these ideas into a rigid state ideology, which he termed “Marxism-Leninism“. This “-ism,” which Marx and Lenin never sanctioned, became the official ideology of the Soviet Union and the Communist International.

Stalin’s primary theoretical innovation was “Socialism in One Country,” developed during his power struggle against Leon Trotsky. This theory rejected the classical Marxist and Trotskyist idea that a socialist revolution could only succeed in the long term if it spread and became a world revolution.

By 1924, revolutions in Germany, Hungary, and elsewhere had failed, leaving the USSR isolated. Trotsky’s theory of “Permanent Revolution” implied that, without international help, the USSR was doomed. Stalin’s “Socialism in One Country” was a pragmatic, nationalist turn. It argued that the USSR could successfully build a “complete Socialist society” by itself (“with the aid of the internal forces of our country“), even while surrounded by capitalist states. This reframed the goal from exporting revolution (which Stalin dismissed as “nonsense“) to building and defending the Soviet state. This pivot transformed international communist movements from independent revolutionary actors into foreign policy tools dedicated to the defense of the USSR, cementing the schism with Trotsky.

IV. The Maoist Development: Revolution for the Global South

Maoism (or Mao Zedong Thought) is a variety of Marxism-Leninism developed by Mao Zedong to apply the ideology to the “agricultural, pre-industrial society” of China.

A. The Revolutionary Subject: The Peasantry as the “Mighty Storm”

Mao’s most radical departure from both Marx and Lenin was his re-evaluation of the revolutionary subject.

- Marxist Orthodoxy: The peasantry is a “scattered, individualistic, petty-bourgeois class“, not a revolutionary one. The proletariat is the only revolutionary class.

- Mao’s Re-evaluation: Based on his 1927 Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan, Mao argued that in a semi-feudal, semi-colonial country like China, the urban proletariat was tiny. The peasantry (comprising 70% of the population) was the “true revolutionary force“.

- Why? Mao saw that the peasants faced the most severe exploitation (from landlords, warlords, and foreign imperialists) and, as the “poor peasants,” had “neither a tile over their heads nor a speck of land under their feet“. They had “nothing to lose.” He described their revolutionary potential as a “mighty storm, like a hurricane, a force so swift and violent that no power, however great, will be able to hold it back,” sweeping their oppressors “into their graves“.

This was a synthesis of populism and Leninism. Mao identified the peasantry as the revolutionary force, but he retained the Leninist instrument—the vanguard party. He argued the peasantry could be a revolutionary force if it was guided by “Communist Party leadership“. Maoism is therefore Marxism-Leninism “applied to the particularities of the Chinese…Revolution“; it is the application of a Leninist vanguard structure to a peasant mass base.

B. The Revolutionary Strategy: Protracted People’s War (PPW)

If the revolutionary base is rural, the revolutionary strategy must be rural. This led Mao to reject the Leninist/Bolshevik model of a quick urban insurrection. Instead, he developed the strategy of Protracted People’s War (PPW), outlined in works like On Protracted War.

PPW is a three-stage military and political strategy:

- Stage 1: Strategic Defensive. The revolutionary forces are weak. The focus is on survival, organization, and political mobilization. They establish “revolutionary base areas” in remote countryside. The primary tactic is guerrilla warfare to harass the enemy, build popular support, and capture weapons.

- Stage 2: Strategic Stalemate. The revolutionary forces grow in strength. The strategy is to “bleed the enemy dry“, expand the base areas, and gain governing experience through programs like land reform. Guerrilla warfare and mobile warfare are used to wear down the enemy.

- Stage 3: Strategic Offensive. The balance of power shifts. The revolutionary army transitions from guerrilla to mobile and conventional warfare. The strategy becomes “encircling and capturing” small cities, then larger ones, from the countryside, leading to the final seizure of power.

PPW is not just a military strategy; it is a political one. Unlike an urban insurrection, which relies on speed and timing, PPW weaponizes time and space. Its center of gravity is not military might, but “maintaining the support of the population“. This makes political work (like land reform) more important than any single battle. This is why Maoists view PPW as a universal strategy for the “global countryside” (Third World) to overwhelm the “global cities” (First World).

C. The Leadership Model: The “Mass Line”

The “Mass Line” is Mao’s organizational innovation, designed to connect the Leninist Party to its new peasant mass base. It is summarized by the slogan “from the masses, to the masses” and represents a cyclical process of leadership:

- From the Masses: The Party (cadres) goes to the people and gathers their “scattered, unsystematic” ideas, “felt needs,” and grievances.

- To the Masses: The Party processes these ideas, “pooling the wisdom” and analyzing them through the “perspective of revolutionary Marxism” and the long-term interests of the masses. It turns these scattered grievances into a systematic political line or policy.

- This concentrated idea is then returned to the masses as a slogan or policy, which the masses then embrace and test in practice, starting the “endless spiral” of refinement over again.

This differentiates it from Lenin’s “Democratic Centralism.” Democratic Centralism is a top-down model of discipline for Party members. The Mass Line is a cyclical model of leadership for the non-Party masses. It was Mao’s theoretical solution to the problem of bureaucratic degeneration (which he saw in Stalin’s USSR), as it forces the Party vanguard to “link…with the masses” and avoid becoming a detached elite. However, it is still a vanguardist model: the Party retains the exclusive right to “process” the ideas and “return” the correct line.

D. The Post-Revolutionary Theory: Continuous Revolution

Mao’s theory of Continuous Revolution (or continuing the revolution under the dictatorship of the proletariat) is his theory for the period after seizing power.

- The Problem: Mao, observing the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death, concluded that seizing power and nationalizing property was not the end of class struggle.

- The Theory: He argued that a new bourgeoisie—”capitalist roaders” or “revisionists“—will inevitably “sneak into the party, the government, the army” and try to restore capitalism from within. He claimed the USSR had done just this, becoming “state capitalist” and “social imperialist” (“socialist in words, imperialist in deeds“).

- The Solution: The revolution must be “continuous“. This requires perpetual struggle within socialist society to identify and purge these “impure” elements.

- The Practice: The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) was the application of this theory. Mao mobilized the youth (Red Guards) to attack the Party-state bureaucracy itself.

This is not the same as Trotsky’s “Permanent Revolution“. Trotsky’s theory is pre-revolutionary (how to get to socialism) and international. Mao’s is post-revolutionary (how to stay socialist) and domestic.

It is a theory of destabilization, positing that the Party-state itself can become the enemy of the revolution.

V. The “Other” Communisms: Major Ideological Antagonists and Divergences

A. Trotskyism: The “Permanent Revolution” (The “Left” Opposition)

Trotskyism emerged as the primary “left” opposition to Stalin’s Marxism-Leninism. Its theories are foundational to understanding the splits within communism.

- The Precondition: Uneven and Combined Development (UCD): This is Trotsky’s theoretical justification for the Russian Revolution. He argued that “backward” countries like Russia do not develop linearly (stage by stage). Instead, they combine “archaic” forms (a semi-feudal peasantry and an absolutist state) with the most “modern” forms (advanced, concentrated industrial factories built with foreign capital). This combining of stages creates a politically weak bourgeoisie (dependent on the Tsar) but a hyper-concentrated and militant urban proletariat.

- The Strategy: Permanent Revolution: Because the weak bourgeoisie is incapable of even completing its own democratic revolution (e.g., land reform, establishing a republic), the proletariat (though a minority) must seize power and lead the peasants. The revolution thus becomes “permanent” in two ways:

- Domestically: It “flows” immediately from democratic tasks (overthrowing the Tsar) directly into socialist tasks (expropriating factories), with no distinct bourgeois “stage” in between. This is a rejection of the Menshevik and later Stalinist “two-stage theory”.

- Internationally: The revolution cannot survive in one backward country. It must spread to and be “rescued” by revolutions in the advanced capitalist countries of Europe. This is the direct antithesis of Stalin’s “Socialism in One Country”.

- The Critique: The Revolution Betrayed: This is Trotsky’s seminal analysis of Stalin’s USSR. He argued the USSR was a “degenerated workers’ state”.

- It remained a Workers’ State because it retained the economic gains of the revolution: nationalized property and a planned economy.

- It was Degenerated because a “parasitic bureaucracy”, led by Stalin, had usurped political power from the masses (the Soviets), destroying all workers’ democracy. This bureaucracy was a “caste,” not a new class.

- Trotsky’s solution was a political revolution to “debureaucratize the bureaucracy” and restore workers’ control, not a social revolution to overturn the nationalized property.

B. Luxemburgism: The “Democratic-Spontaneist” Critique (The “Libertarian” Marxist)

Rosa Luxemburg represents a profound libertarian-Marxist critique of the Leninist model, emphasizing mass democracy and spontaneity.

- The Engine of Revolution: The “Mass Strike” and Spontaneity: Based on her analysis of the 1905 Russian Revolution, Luxemburg argued against the Leninist conception of a party commanding a revolution. For her, the “Mass Strike” is not a tactic that can be “called” or “decided” by a party. It is an organic, historical process where economic and political struggles spontaneously merge and escalate, creating revolutionary consciousness through action. The Party’s role is not to command the spontaneous movement, but to agitate, educate, and provide clear political leadership to the already-moving masses.

- The Critique of Lenin and the Bolsheviks:

- In 1904, she critiqued Lenin’s “ultra-centralism”, warning it was a “Blanquist” (conspiratorial) model that would stifle the “spontaneous creativeness” of the workers and make the Central Committee the “only thinking element”.

- Later, in The Russian Revolution (written in prison in 1918), she passionately supported the Bolsheviks for making the revolution (“all the revolutionary honor…which western Social-Democracy lacked”). However, she prophetically condemned their post-revolutionary actions:

- Their suppression of democratic freedoms, including the press, assembly, and the Constituent Assembly.

- She issued her famous maxim: “Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently”.

- She warned that without this democratic life, the Dictatorship of the Proletariat would inevitably become a “dictatorship… of a handful of politicians,” leading to the “rise of a new bureaucracy”.

- Luxemburg advocated for a “third way”: both revolution and multi-party socialist democracy, believing the latter was the only way for the former to succeed.

C. Anarcho-Communism: The Rejection of the State (The “External” Critique)

Anarcho-Communism is not a “Marxist” ideology; it is a separate branch of communism that is fundamentally opposed to Marxism’s core tenets on the state. Its key thinker was Peter Kropotkin.

- Economic Vision: “Well-Being for All”: Based on “Mutual Aid” (cooperation) as the driving force of human progress, not “class struggle”. It calls for the immediate abolition of both private property and the wage system. It rejects the socialist principle “to each according to his deeds”. Instead, all wealth is a collective inheritance, and goods should be distributed immediately according to need—the “Right to Well-Being for All”.

- The Fundamental Critique of the State and DoP: This is the absolute point of divergence. Anarcho-Communists reject all states and all forms of hierarchy as inherently oppressive. They explicitly reject the “dictatorship of the proletariat”. Anarchist theorists like Joseph Déjacque argued that any dictatorship, even a “proletarian” one, is “inherently reactionary and counter-revolutionary”. Marxists see the (proletarian) state as a necessary transitional tool to defeat the bourgeoisie. Anarcho-Communists see the tool itself as the poison. They argue that power corrupts, and a “vanguard party” seizing control of an “authoritarian state” will not lead to the “withering away of the state.” It will only create a new ruling class and a new tyranny, confirming the 19th-century predictions of Marx’s rival, Mikhail Bakunin. The goal must be to abolish the state at the same time as capitalism, replacing it with “voluntary associations”.

VI. Synthetic Analysis: A Comparative Matrix of Core Ideological Contentions

A. Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Revolutionary Ideologies

| Ideology | Key Thinkers | Core Text(s) | Primary Revolutionary Class | Theory of Party/Organization | Revolutionary Strategy | View on Post-Revolutionary State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Marxism | Marx, Engels | The Communist Manifesto, Das Kapital, Critique of the Gotha Programme | Urban Proletariat | A mass working-class party (implied). | Spontaneous revolution from mature capitalism. | “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” as a transitional workers’ state that “withers away”. |

| Marxism-Leninism | Lenin (Adaptor), Stalin (Codifier) | What Is to Be Done?, Imperialism, The State and Revolution | Urban Proletariat | Vanguard Party based on Democratic Centralism. | Quick Urban Insurrection in the “weakest link” of imperialism. | One-party state as the DoP. “Socialism in One Country”. |

| Maoism | Mao Zedong | Report on Hunan Peasant Mvmt, On Protracted War, On Contradiction | Rural Peasantry (led by the Party). | Leninist Vanguard plus the Mass Line. | Protracted People’s War (Rural guerrilla war encircling cities). | DoP, but with Continuous Revolution to purge “capitalist roaders” within the Party. |

| Trotskyism | Leon Trotsky | Permanent Revolution, The Revolution Betrayed, History of the Russian Rev. | Urban Proletariat | Leninist Vanguard Party. | Permanent Revolution (democratic flows into socialist; must be international). | USSR is a “Degenerated Workers’ State” requiring a political (not social) revolution. |

| Luxemburgism | Rosa Luxemburg | The Mass Strike, Reform or Revolution?, The Russian Revolution | The Proletariat as a whole | Mass Spontaneity; Party as agitator, not director. | Mass Strike (organic, spontaneous escalation of struggle). | DoP with multi-party socialist democracy and full freedoms. Rejects one-party rule. |

| Anarcho-Communism | Peter Kropotkin, Joseph Déjacque | The Conquest of Bread, Mutual Aid | “The People”; all oppressed. | Decentralized, voluntary associations; mutual aid federations. | Social revolution to immediately abolish state and capital. | Immediate and total abolition of the state. Rejects DoP as inherently tyrannical. |

B. Narrative Analysis of Core Contentions

- The Revolutionary Subject (Proletariat vs. Peasantry): This is the central adaptation of Maoism. Classical Marxism and Leninism are “urban” ideologies focused on the industrial proletariat. Maoism is a “rural” ideology that transfers the revolutionary mandate to the peasantry. This fundamentally shifted Marxism from a “First World” to a “Third World” context.

- Revolutionary Strategy (Insurrection vs. PPW): The Leninist model is a quick, urban “blitzkrieg” insurrection (like the 1917 October Revolution) focused on decapitating the state. The Maoist model is a rural, long-term “war of attrition” (PPW) focused on building a new state and army from scratch in the countryside and bleeding the old one dry.

- The Nature of the Party (Vanguard vs. Spontaneity): This is the debate over how to lead. Lenin’s “Democratic Centralism” is a top-down, quasi-military model of command and discipline. Mao’s “Mass Line” is a consultative vanguardism, a cyclical method of leadership to prevent bureaucratic detachment. Luxemburg’s “Spontaneity” rejects command entirely, arguing the party must follow and articulate the organic movement of the masses.

- The Revolutionary Timeline (Stageism vs. Permanent vs. Continuous): This is the most complex theoretical dispute.

- Stalinist Two-Stage Theory: A country must first have a bourgeois-democratic revolution and then, at a later date, a socialist one.

- Mao’s New Democracy: A modification where the Communist Party leads a coalition of classes (proletariat, peasantry, petty bourgeoisie) to complete the first (democratic) stage as the necessary precondition for the second (socialist) stage.

- Trotsky’s Permanent Revolution: A rejection of stageism. The proletariat must immediately and continuously push the bourgeois revolution into a socialist one.

- Mao’s Continuous Revolution: This theory is entirely different from Trotsky’s. Trotsky’s theory is pre-revolutionary and international. Mao’s is post-revolutionary and domestic, arguing for the perpetual need for class struggle within the socialist state to prevent capitalist restoration.

The Post-Revolutionary State (DoP vs. Bureaucracy vs. Abolition)

This is the “end-game” debate.

- Lenin/Stalin: The One-Party State is the legitimate expression of the DoP.

- Trotsky: The state became a degenerated bureaucratic “caste” over the proletariat, requiring a new political revolution.

- Mao: The state/party is constantly at risk of producing a new bourgeoisie from within, requiring a cultural revolution to purge it.

- Luxemburg: The one-party state is a dictatorship over the proletariat and must be replaced by socialist democracy to be legitimate.

- Anarcho-Communism: The state itself is the enemy and must be abolished from day one.

Conclusion: The Legacy and Relevance of Divergent Marxisms

A. Summary of Findings

“Communism” is not a monolith. It is a dynamic, deeply factionalized intellectual and political tradition. The “differences” between Marxism-Leninism, Maoism, and its “other” variants are not arbitrary. They represent concrete, strategic answers developed by revolutionaries to address specific, unanticipated historical problems:

- Leninism answered: “How to have a revolution in an autocratic ‘weakest link,’ not an advanced industrial state?”.

- Stalinism (Marxism-Leninism) answered: “How to save the revolution when it is isolated and world revolution has failed?”.

- Maoism answered: “How to have a revolution in an agrarian, semi-colonial nation with no proletariat?”.

- Trotskyism answered: “What went wrong in the USSR, and how do we fix it?”.

- Luxemburgism answered: “How can we have a revolution without sacrificing the democratic, libertarian soul of socialism?”.

- Anarcho-Communism answered: “Is a ‘revolutionary state’ a fatal contradiction in terms?”.

B. Enduring Influence

These 19th and 20th-century ideological fissures are not merely historical. Their influence persists. Contemporary Maoist movements continue to wage Protracted People’s Wars in various parts of the “global countryside”. Trotskyist parties remain active globally, organized into various “Internationals.” The libertarian-socialist and anarchist critiques of state power —which echo the warnings of Luxemburg and Kropotkin—find new resonance in contemporary movements skeptical of centralized authority. The 21st-century legacies of these ideologies demonstrate that these fundamental questions—about the revolutionary subject, the strategy, the party, and the state—remain unresolved and continue to shape political thought and action.