Long-Term EdTech Impact: Longitudinal Measurement Framework

Executive Summary: The Shift from Adoption to Institutionalization

The integration of technology into K-12 and higher education environments has historically been measured by “deployment metrics”—ratios of devices to students, bandwidth capacity, and software licensing acquisition. However, the presence of technology does not guarantee pedagogical transformation or sustained educational impact. As schools move beyond the initial phases of purchasing and installation, the evaluative focus must shift toward longitudinal impact measurement—tracking how teaching practices evolve over time, how deeply technology is embedded into the curriculum, and whether these changes persist across semesters and school years.

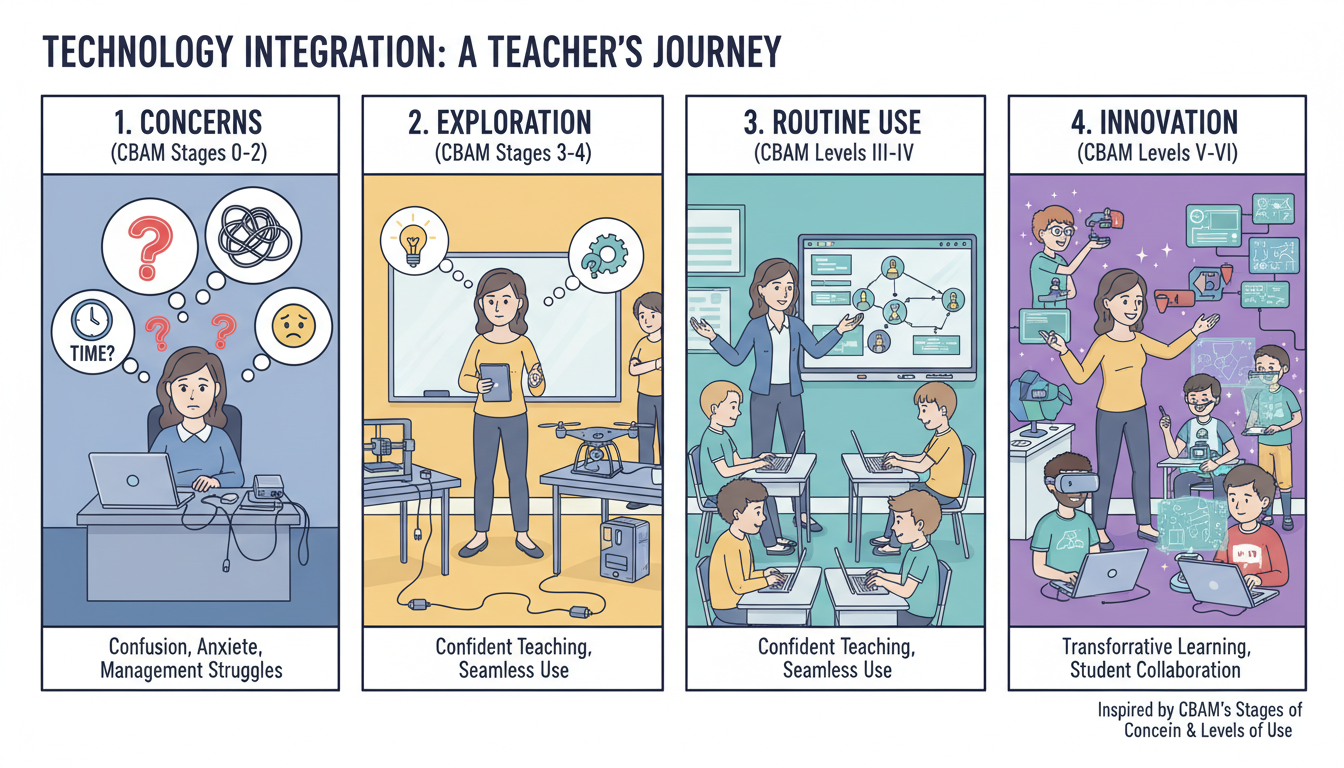

Sustained change in educational technology is not a singular event but a developmental process. Research indicates that “one-time success” or “short-term retention” metrics often fail to capture the complexities of teacher adoption and the eventual institutionalization of practice. To measure true growth, educational leaders must employ longitudinal tracking methods that follow the same cohorts of teachers over extended periods, utilizing a blend of quantitative tracking and qualitative inquiry. This report outlines a comprehensive methodology for designing simple yet robust longitudinal studies, grounded in established theoretical frameworks such as the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) and the Technology Integration Matrix (TIM). It provides a roadmap for shifting from “snapshot” evaluations to “motion picture” analysis of classroom practice.

The core thesis of this report is that sustained technology integration is a human process, not a technical one. Therefore, measurement tools must track human variables—attitudes, concerns, behaviors, and pedagogical shifts—alongside technical proficiency. By leveraging accessible tools like spreadsheets and dashboards and employing basic qualitative research methods like structured interviews and focus groups, districts can generate deep, actionable insights that drive professional development and ensure long-term return on investment (ROI).

The findings synthesized in this report suggest that the “Implementation Dip”—a temporary drop in performance and confidence as teachers grapple with new tools—is an inevitable phase of the integration lifecycle. Longitudinal tracking is the only methodology capable of distinguishing this temporary dip from permanent failure. Furthermore, the data indicates that peer-to-peer collaboration and “Teaching Squares” are far more effective predictors of long-term adoption than isolated workshops. Ultimately, this report argues for a democratization of data, where simple, transparent tracking mechanisms empower teachers to own their professional growth trajectories, transforming evaluation from a punitive measure into a supportive, developmental tool.

Section I: The Landscape of Evaluation and the Longitudinal Imperative

1.1 The Limitations of Snapshot Evaluation

In the landscape of educational technology, the “pilot study” is ubiquitous. Schools implement a new tool—VR headsets, a new LMS, or 1:1 tablets—and evaluate it after six months. Invariably, these short-term evaluations yield “honeymoon effect” data: excitement is high (Innovation), usage is frequent (Novelty), and self-reported satisfaction is positive. However, research consistently shows that these short-term gains often evaporate within 12-18 months as the novelty wears off, technical glitches accumulate, and the “Management” burden sets in.

Snapshot evaluations (cross-sectional data) fail to capture the Implementation Dip. Fullan’s change theory suggests that performance often drops during the early stages of adoption as teachers struggle to master new skills. A snapshot taken during this dip might erroneously deem a successful program a failure. Conversely, a snapshot taken during the “peak of inflated expectations” might overestimate success. Only longitudinal data—tracking the same users through the dip and out the other side—can accurately assess the viability of an integration initiative.

Furthermore, snapshot evaluations often rely on “vanity metrics”—counts of logins, downloads, or page views. While these metrics prove that the technology is being accessed, they offer zero insight into whether it is being integrated into a meaningful pedagogical strategy. A teacher might log in to a sophisticated adaptive learning platform daily (high usage metric) but use it only as a “digital babysitter” while they grade papers (low integration level). Without longitudinal qualitative inquiry—observing the classroom in October, and again in April—this distinction remains invisible to administration.

1.2 Defining Sustained Change: Institutionalization

“Sustained change” in this context is defined not merely as the continued purchase of software licenses, but as the institutionalization of pedagogical shifts. Institutionalization is the phase where the innovation becomes “the way we do things around here.” It is characterized by resilience; the practice persists even when the enthusiastic “early adopter” principal leaves or when the grant funding expires.

This report identifies three key markers of sustained change that longitudinal studies must track:

- From Episodic to Routine: Technology use moves from being a “special event” (going to the computer lab on Fridays) to a seamless part of the daily workflow (using a tablet to document science experiments as they happen). This shift is captured by the CBAM “Levels of Use” framework, specifically the move from Level 3 (Mechanical) to Level 4A (Routine).

- From Teacher-Centered to Student-Centered: The locus of control shifts from the teacher delivering content to the student creating content. This is the ultimate goal of frameworks like TIM and SAMR, but it is a multi-year developmental arc. In the first year, a teacher might use an interactive whiteboard to lecture (Teacher-Centered). By year three, students might be using the same board to present their own findings (Student-Centered).

- Resilience and Adaptability: The integration survives technical glitches and curriculum changes. A teacher with “sustained” integration skills doesn’t abandon technology when the wifi goes down; they have a backup plan. They also adapt their use of the tool as the curriculum evolves, demonstrating the “Refinement” and “Renewal” levels of use.

1.3 The Role of the “Researcher-Practitioner”

To measure these complex shifts, school leaders must adopt the mindset of a “researcher-practitioner.” This does not require a Ph.D. in statistics; it requires curiosity, consistency, and a systematic approach to inquiry. It involves asking the same questions, to the same people, over an extended period.

The methods outlined in this report—simple spreadsheets, structured interviews, and observational rubrics—are designed to be executed by instructional coaches, department heads, and district administrators without requiring external consultants. This democratization of research is crucial. When teachers and internal leaders conduct the research, the findings are more likely to be trusted and acted upon. Action research, where educators study their own schools to improve them, empowers the staff and frames data collection as a tool for professional growth rather than external judgment.

Section II: Theoretical Architectures for Measuring Change

To effectively measure the long-term impact of technology integration, one must utilize robust theoretical frameworks that describe how change occurs. Without a map, it is impossible to track the journey. The following frameworks provide the necessary vocabulary and metrics for longitudinal analysis.

2.1 The Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM)

The Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) is widely regarded as the most rigorous framework for measuring educational change. Unlike models that focus solely on the technology (hardware/software), CBAM focuses on the individual user. It acknowledges that “organizations don’t change; individuals do”. For longitudinal tracking, CBAM provides three distinct diagnostic dimensions: Stages of Concern, Levels of Use, and Innovation Configurations.

2.1.1 Diagnostic Dimension 1: Stages of Concern (SoC)

The SoC framework tracks the emotional and cognitive progression of a teacher interacting with a new technology. In a longitudinal study, the researcher administers the SoC Questionnaire (SoCQ) or conducts SoC interviews annually. The progression is not strictly linear, but generally moves from “Self” to “Task” to “Impact” concerns over time.

| Stage | Focus | Typical Teacher Statement (The “Voice” of the Stage) | Longitudinal Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0. Unconcerned | Unrelated | “I’m more worried about the new bus schedule than this new software.” | Baseline. If this persists in Year 2, adoption has failed to launch. |

| 1. Informational | Self | “I’ve heard about it, but I don’t know the details. What does it require of me?” | Typical for Year 1 / Semester 1. Indicates awareness but lack of engagement. |

| 2. Personal | Self | “Will I lose control of the class? Will this double my grading time?” | High anxiety. Intervention needed: Reassurance & policy clarity. Common in the first 6 months. |

| 3. Management | Task | “I spend 20 minutes just getting students logged in. The wifi keeps dropping.” | The “Implementation Dip.” If a cohort stays here >1 year, the tech infrastructure or training is likely faulty. |

| 4. Consequence | Impact | “I see that my students are more engaged, but are they learning the core concepts?” | The turning point to sustained integration. Focus shifts to students. |

| 5. Collaboration | Impact | “I want to share this lesson with Mr.” |

Jones so we can run a joint project.

Indicator of institutionalization. Silos are breaking down.

6. Refocusing

Impact

“This software is okay, but I found a plugin that does it better. Let’s try that.”

Mastery. The teacher is now an innovator.

Application: By plotting the “Peak Stage of Concern” for a cohort over 3 years, a district can see if the group is maturing. A “wave” motion is expected. If the wave flatlines at Stage 3, the district must address “Management” obstacles (e.g., better wifi, easier logins) before pushing for “Transformation”. This longitudinal view prevents the common mistake of offering advanced pedagogical training (Stage 4/5) to teachers who are still struggling with logins (Stage 3).

2.1.2 Diagnostic Dimension 2: Levels of Use (LoU)

While SoC measures feelings, LoU measures behaviors. This distinction is vital because teachers often report high enthusiasm (SoC) while exhibiting low actual usage (LoU) due to barriers. The LoU framework describes eight levels of behavioral engagement.

- Non-Use (Levels 0-2): Ranging from ignorance (Level 0) to seeking information (Level 1) to preparing to use (Level 2).

- Level 3 (Mechanical Use): The user is disjointed and inefficient. They are “coping.” Crucial Insight: High scores in Level 3 are good in the first year—it means they are trying. However, Level 3 is unsustainable long-term. Teachers will eventually either quit (revert to Non-Use) or master the tool (move to Routine).

- Level 4A (Routine): The use is stable and comfortable. This is “sustained integration.” The teacher no longer has to “think” about the tech; it is automatic.

- Level 4B (Refinement): The teacher varies the use to increase impact on students. They are tweaking the process based on student data.

- Level 5 (Integration): The teacher combines efforts with colleagues.

- Level 6 (Renewal): The teacher re-evaluates the quality of use and seeks major modifications.

Longitudinal Application: Use the LoU Branching Interview Protocol to categorize teachers. Tracking the percentage of staff at “Routine” (4A) or higher is a key metric for institutionalization. A successful longitudinal trajectory shows a cohort moving from Level 2 (Preparation) to Level 3 (Mechanical) in Year 1, and settling into Level 4A (Routine) by Year 2 or 3.

2.1.3 Diagnostic Dimension 3: Innovation Configurations

An IC Map describes what the innovation actually looks like in practice, ranging from “Ideal” to “Unacceptable.” This tool is essential for defining “fidelity of implementation.” Without an IC Map, one teacher might define “using the LMS” as uploading a PDF syllabus (low fidelity), while another defines it as running interactive discussion boards (high fidelity).

- Example: For “Student Collaboration via Cloud Docs”:

- Variation A (Ideal): Students co-edit in real-time, commenting on peers’ work.

- Variation B (Acceptable): Students type individually and share the final link.

- Variation C (Unacceptable): Students type individually, print the doc, and hand it in.

Application: Developing an IC Map allows observers to specifically code what they see in classrooms, creating a standard for observation. This standardization is critical for longitudinal comparison—it ensures that “Usage” means the same thing in Year 3 as it did in Year 1.

2.2 The Technology Integration Matrix (TIM)

While CBAM focuses on the adopter, the Technology Integration Matrix (TIM) focuses on the pedagogy and the learning environment. Developed by the Florida Center for Instructional Technology, TIM provides a vocabulary for describing the complexity of integration.

TIM intersects five levels of technology integration (Entry, Adoption, Adaptation, Infusion, Transformation) with five characteristics of meaningful learning environments (Active, Collaborative, Constructive, Authentic, Goal-Directed). This creates a 25-cell matrix.

- Entry: The teacher uses technology to deliver curriculum content to students (e.g., lecture slides).

- Adoption: The teacher directs students in the conventional and procedural use of technology tools (e.g., “Open the app and click start”).

- Adaptation: The teacher facilitates students in exploring and independently using technology tools (e.g., students choose which video editor to use).

- Infusion: The teacher provides the learning context and the students choose the technology tools to achieve the outcome.

- Transformation: The teacher encourages the innovative use of technology tools. Higher-order thinking activities that would be impossible without technology.

Longitudinal Application: By using the TIM-O (Observation Tool), a researcher can generate a “TIM Profile” for a teacher. Over 3 years, we want to see movement from the “Entry/Adoption” left-hand side of the matrix to the “Infusion/Transformation” right-hand side. This shift proves that the quality of teaching is improving, not just the quantity of tech use.

2.3 SAMR and ACOT: Developmental Context

- SAMR (Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition): This model is excellent for quick, reflective checks (“Is this task Substitution or Redefinition?”). However, it lacks the behavioral detail of CBAM and the environmental detail of TIM. In a longitudinal study, SAMR serves well as a self-assessment rubric for teachers to evaluate their own lesson plans over time.

- ACOT (Apple Classrooms of Tomorrow): The ACOT research remains relevant for its identification of the “Appropriation” phase. ACOT found that it typically takes 3-5 years for teachers to reach the stage where they appropriate technology as a personal tool. This finding is a critical benchmark for managing stakeholder expectations; it provides empirical evidence that sustained change is a marathon, not a sprint.

Section III: Designing the Longitudinal Study: Cohorts and Methodology

To measure “sustained change,” the research design must control for the variables of time and participant continuity. Cross-sectional studies (surveying different random groups each year) fail to show individual growth trajectories. A longitudinal cohort design is essential.

3.1 Cohort Methodology: Following the Same Teachers

The most effective method for tracking growth is to select a representative cohort of teachers and follow them for a minimum of three years.

3.1.1 Selection Strategies and Retention

Tracking every teacher in a large district generates excessive data noise. A “Sentinel Cohort” of 30-50 teachers can provide representative data.

- Stratified Random Sampling: Select teachers to mirror the district’s makeup. Ensure representation from different grade levels (Elementary, Middle, High), subject areas (STEM, Humanities, Arts), and experience levels (Novice, Veteran).

- New Teacher Cohorts: Tracking a cohort of first-year teachers for their first 3-5 years provides critical data on how induction programs and early mentorship influence long-term technology habits. Research suggests the first three years are pivotal for retention and habit formation.

- Retention Strategy: Longitudinal studies suffer from attrition (teachers leaving or dropping out). To maintain the cohort:

- Incentives: Offer Continuing Education Units (CEUs) or “Micro-credentials” for participation in the study (interviews/surveys).

- Feedback Loops: Promise and deliver personalized data reports to the participants. Teachers are more likely to stay involved if the data helps them reflect on their own practice.

3.1.2 The “Teaching Square” Model

For a more qualitative, peer-driven approach, organize the cohort into “Squares” (groups of 4).

- Mechanism: In a square, Teacher A observes B, B observes C, C observes D, and D observes A. They do not evaluate; they “mirror” what they see using the TIM or LoU protocols.

- Longitudinal Benefit: The “Square” stays together for a year or more. The trust built allows for deeper vulnerability. Teachers are more likely to admit to “Personal” or “Management” concerns to a peer than to an administrator. This yields high-validity qualitative data regarding the true state of integration.

3.2 Timeframes and Intervals

Longitudinal does not mean “once a year.” To capture the nuance of change—including the inevitable “implementation dip”—data should be collected at multiple strategic intervals.

| Timeframe | Activity | Tool | Metric Captured | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 – Fall (Aug) | Baseline Survey | TUPS / SoCQ | Attitudes, Initial Skills (Entry Level) | Establish the starting point. |

| Year 1 – Fall (Oct) | Initial Interview | CBAM LoU Interview | Behavioral Baseline (Non-Use/Orientation) | Identify early barriers (“Survival Mode”). |

| Year 1 – Spring (Apr) | Classroom Observation | TIM-O / IC Map | Pedagogical Practice (Mechanical Use?) | Assess fidelity of implementation. |

| Year 1 – Summer | Data Review 1 | Spreadsheet Analysis | Identification of the “Implementation Dip” | Plan PD for Year 2 based on “stuck” points. |

| Year 2 – Fall | Follow-up Survey | SoCQ | Shift in concerns (Self -> Task?) | Measure emotional maturation. |

| Year 2 – Spring | Observation + Focus Group | TIM-O + Focus Group | Practice refinement; Cultural barriers | Dig deeper into cultural enablers/blockers. |

| Year 3+ | Annual Maintenance | LoU Interview | Check for “Routine” or “Refinement” status | Confirm institutionalization. |

3.3 Mixed Methods Approach

A robust report must combine numbers with narratives. Quantitative data (usage logs, survey scores) tells you what is happening. Qualitative data (interviews, observations) tells you why.

- Sequential Explanatory Design: Collect quantitative data first (e.g., a survey showing a drop in usage), then use qualitative methods (interviews) to explain the drop. Example: Survey shows LMS logins dropped in October.”

Interviews reveal that the wifi network was unstable that month, causing teachers to abandon the tool.

- Convergent Parallel Design: Collect survey data and conduct interviews simultaneously, then compare the results to look for contradictions. Example: Teachers say they are transforming learning (High Self-Report), but observations show only substitution (Low TIM Score). This discrepancy highlights a need for PD on what “transformation” actually looks like.

Section IV: Quantitative Instrumentation and Simple Tracking

Complex, expensive software systems are not required to conduct high-quality longitudinal research. In fact, standard office tools (spreadsheets) and simple cloud-based dashboards are often superior because they allow for complete customization and remain accessible even if a specific vendor contract is cancelled.

4.1 Designing the “Master Tracker” Spreadsheet

A single, well-structured spreadsheet can serve as the central database for a multi-year study. This “Master Tracker” is the engine of the longitudinal analysis.

4.1.1 Data Structure Guidelines

The spreadsheet should be organized with rows representing individual teachers (anonymized) and columns representing time points and metrics.

- Tab 1: Demographics & Codes:

- Teacher_ID (e.g., T-101) – Crucial for anonymization.

- School_Site

- Grade_Level

- Subject_Area

- Years_Experience

- Cohort_ID (e.g., Cohort_2024)

- Tab 2: Longitudinal Data (Wide Format):

- T_ID

- Y1_Fall_SoC_Stage

- Y1_Fall_LoU_Level

- Y1_Spring_TIM_Score

- Y2_Fall_SoC_Stage

- Y2_Fall_LoU_Level

- …and so on.

- Tab 3: Professional Development Log:

- T_ID

- Date

- PD_Topic

- Hours

- Artifact_Link (Link to a lesson plan or student work sample).

4.1.2 Formulas for Insight

Using simple Excel/Google Sheets formulas allows for automated analysis of growth.

- Calculating Growth: = (Y2_Score – Y1_Score) / Y1_Score. This formula calculates the percentage growth in self-efficacy or usage frequency year-over-year.

- Identifying “Stuck” Teachers: =IF(AND(Y1_LoU=”Mechanical”, Y2_LoU=”Mechanical”), “FLAG”, “OK”). This logic visually flags teachers who have not progressed from “Mechanical Use” after a full year. These are the teachers who need targeted coaching intervention, rather than generic PD.

- Cohort Aggregation: Use Pivot Tables to group data by School or Department. This allows you to say, “The Science Department is progressing faster than the Math Department,” triggering an investigation into why (e.g., maybe Science has a better mentor).

4.2 Visualizing Growth: Dashboards

Dashboards provide an “at-a-glance” view of longitudinal trends, making complex data digestible for stakeholders. Tools like Google Looker Studio or Microsoft Power BI are free/low-cost and connect directly to the Master Tracker spreadsheet.

4.2.1 The “Teacher Growth” Dashboard (Teacher-Facing)

This dashboard can be shared with the individual teacher as a form of feedback.

- Visual: A line graph tracking their personal “Stage of Concern” over 3 years.

- Insight: Seeing the line move from “Self” (Stage 1-2) to “Impact” (Stage 4-5) validates their professional growth. It turns the evaluation into a reflective tool.

4.2.2 The “District Health” Dashboard (Admin-Facing)

- Visual: A “Sankey Diagram” or flow chart showing the movement of the cohort between levels. (e.g., “In 2023, 50 teachers were at ‘Entry’. In 2024, 30 moved to ‘Adoption’ and 20 stayed at ‘Entry’.”)

- Visual: A “Heat Map” of the TIM matrix.

- Data: The frequency of observations in each cell.

- Insight: If 80% of observations cluster in “Entry-Passive” (top left), the district knows that despite buying 1:1 devices, teaching has not changed. This is a powerful visual for School Boards to justify investment in coaching rather than just hardware.

4.3 Survey Instruments

Surveys allow for broad data collection across the cohort. However, “survey fatigue” is a risk in longitudinal studies. Keep instruments short and focused.

- Stages of Concern Questionnaire (SoCQ): A standard 35-item questionnaire that mathematically determines a teacher’s peak stage of concern. Administer this at the beginning and end of each year.

- Technology Uses and Perceptions Survey (TUPS): Assesses teacher attitudes and frequency of tool use. Helpful for correlating belief with practice.

Section V: Qualitative Inquiry: Unearthing the “Why”

While quantitative data tracks the status of integration (e.g., “Usage is down 10%”), qualitative inquiry reveals the mechanism of that status (e.g., “Usage is down because the new update deleted our saved lesson plans”). Learning basic qualitative methods allows the evaluator to understand the cultural, contextual, and personal factors that support or inhibit growth.

5.1 The Qualitative Research Cycle

The process of qualitative inquiry follows a rigorous cycle, not random anecdote collection. It involves: Data Collection -> Data Managing -> Reading/Memoing -> Describing/Classifying (Coding) -> Representing -> Interpreting.

5.2 Interviewing for Longitudinal Insight

Interviews in a longitudinal study must be consistent to allow for comparison over time. You cannot just “chat.” You must use a structured protocol.

5.2.1 The CBAM LoU Interview Protocol

This protocol acts as a decision tree to pinpoint exactly how a teacher is using an innovation.

- Opening: “Are you currently using?” (If no, branch to Non-Use questions).

- User-Oriented: “What kind of work does it require of you? How does it affect your time?” (Probes for Management concerns).

- Student-Oriented: “Have you seen any changes in student outcomes? How do you assess those?” (Probes for Consequence concerns).

- Modification: “Have you made any changes to how you use it recently? Why?” (Probes for Refinement).

- Collaboration: “Do you discuss your use with other teachers?” (Probes for Collaboration).

Tip: Record and transcribe these interviews (using AI tools like Otter.ai or Zoom transcripts) for coding. Listening to the recording allows you to hear the tone—is the teacher excited or exhausted?

5.2.2 Behavioral Event Interviewing (BEI)

Ask teachers to describe a specific recent lesson. “Walk me through the lesson you taught last Tuesday. What did you do? What did the students do?” This avoids the vague generalizations of self-reporting like “I use computers often” and grounds the data in actual practice.

5.3 Focus Groups: Leveraging Group Dynamics

Focus groups are efficient for gathering data from cohorts (e.g., “The 3rd Grade Team”) and observing the cultural norms of the group.

5.3.1 Guide Design

- The Warm-Up: “What is one ‘win’ and one ‘fail’ you’ve had with technology this week?” (Low stakes).

- The Longitudinal Reflection: “Think back to when we started this initiative 2 years ago. How has your daily routine changed? Is it better or worse?”

- The Barrier Probe: “If you stopped using this tool tomorrow, what would happen? Would you miss it?” (Tests for institutionalization—if they wouldn’t miss it, it’s not institutionalized).

5.3.2 Managing Dynamics and Bias

- The Dominator: The tech-savvy teacher who answers everything. Facilitator Move: “That’s a great example, Sara. I’d like to hear from someone who feels less confident with the tool. How is it for you?”

- Groupthink: If everyone agrees instantly, play Devil’s Advocate. “Some other schools have reported X problem. Have any of you experienced that?”

- Analysis: Note not just what is said, but who says it. Do early adopters dominate? Do skeptics remain silent? These dynamics are data points regarding the school’s culture.

5.4 Classroom Observations: The Truth on the Ground

Self-reporting (surveys/interviews) often inflates the reality of integration. Direct observation is the check against this bias.

- The TIM-O (Technology Integration Matrix – Observation): A validated tool for observing lessons. The observer notes the activity and maps it to the matrix.

- Procedure: Observe for 20-30 minutes. Focus on student behavior, not just teacher behavior. Is the student an active learner or a passive recipient?

- Walkthrough Protocols (OPTIC): Short, frequent 5-10 minute observations (e.g., the “OPTIC” protocol) can provide a high volume of data points to track frequency of use. OPTIC stands for Observe, Ponder, Talk, Implement, Check.

- Inter-Rater Reliability: To ensure data validity, two observers should watch the same lesson periodically and compare scores. If Observer A rates it “Adoption” and Observer B rates it “Transformation,” they need to calibrate their definitions.

5.5 Qualitative Data Analysis (Coding)

Coding is the process of labeling segments of text (interview transcripts, observation notes) to identify themes. It turns anecdotes into data.

- Open Coding: Read through the data and apply descriptive labels.

- Quote: “I tried to use the VR headsets, but the battery died halfway through.” -> Code: Technical Barrier / Hardware Failure.

- Quote: “My kids were so excited to see the volcano erupt.” -> Code: Student Engagement.

- Axial Coding (Categorization): Group the labels into categories.

- “Hardware Failure” + “Wifi Drop” = Infrastructure Barriers.

- “Student Engagement” + “Deep Questions” = Pedagogical Impact.

- Thematic Analysis: Identify the overarching narrative.

- Theme: “Teachers are willing to experiment but are hindered by unreliable hardware.”

- Longitudinal Comparison: Compare the codes from Year 1 to Year 3.

- Year 1 Dominant Codes: “Fear,” “Time,” “Passwords.”

- Year 3 Dominant Codes: “Student Projects,” “Assessment,” “Collaboration.”

- Analysis: The shift in codes proves the cohort has moved from Management Concerns to Impact Concerns.

This qualitative proof is often more compelling than a survey score.

- Tools: Simple color-coding in Microsoft Word or Excel is sufficient for most district-level reports. Specialized software (NVivo) is optional.

Section VI: Analysis and Interpretation

Collecting data is useless without rigorous analysis. This section details how to synthesize the “Mixed Methods” data into a coherent story of change.

6.1 Triangulation

Triangulation validates findings by cross-referencing data sources. It protects the study from the bias of any single instrument.

| Data Source A (Survey) | Data Source B (Observation) | Data Source C (Interview) | Synthesis / Truth |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Self-Reported Usage | Low TIM Score (Entry Level) | “I use the projector every day.” | Conflation: The teacher equates “using hardware” with “integration.” Needs PD on student-centered pedagogy. |

| Low Self-Reported Confidence | High TIM Score (Adaptation) | “I feel like I’m losing control.” | Growing Pains: The teacher is effective but anxious. Needs reassurance, not retraining. |

| High Concern (Management) | Low Usage | “The login process is broken.” | Infrastructure Block: The barrier is technical, not pedagogical. Fix the IT, don’t blame the teacher. |

6.2 Root Cause Analysis

When longitudinal data shows a “stalled” cohort (e.g., stuck at Level 3 Mechanical Use), apply Root Cause Analysis (The “5 Whys”) to the qualitative data.

- Observation: Teachers are not using the new tablets.

- Why? They say they aren’t charged.

- Why? The charging carts are locked in the library.

- Why? The librarian is afraid of theft.

- Why? There is no policy for lost devices.

- Root Cause: Lack of policy, not lack of teacher interest. The intervention should be policy creation, not teacher PD.

Section VII: Indicators of Institutionalization: Measuring Sustainability

When can a district declare “success”? When the change is self-sustaining. This requires looking beyond test scores.

7.1 Leading vs. Lagging Indicators

In education, we often rely too heavily on lagging indicators (test scores, graduation rates), which take years to manifest and are influenced by countless variables (poverty, home life). Leading indicators provide early warnings and allow for mid-course correction.

| Metric Type | Definition | Examples for Tech Integration | Longitudinal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leading Indicators | Predictive measures; inputs and early behaviors. |

|

High. These change first. If self-efficacy drops, usage will drop 6 months later. If “Square” meetings stop, collaboration is dying. |

| Lagging Indicators | Output measures; results of past actions. |

|

Moderate. These take 3-5 years to show valid shifts and are “noisy” data. Valid mainly for correlating with long-term “Routine” use. |

7.2 Sustainability Rubrics

Use a rubric to assess the system, not just the teachers. If the system is fragile, the integration will collapse when the grant ends.

- Resource Alignment: Is tech replacement built into the base operational budget? Or is it dependent on one-time funds?

- Leadership: Do site principals model technology use? Is there a designated “Tech Lead” on campus who is not the principal?

- Community Support: Do parents expect technology integration? (Parents are a stabilizing force for institutionalization).

- Score: If a district scores high on “Resource Alignment” but low on “Leadership,” the initiative is at risk of crumbling when funding dries up.

Section VIII: Case Studies and Applied Contexts

Examining how major districts have navigated this process illuminates the practical application of these frameworks.

8.1 Case Study: Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) – The Ecosystem Approach

FCPS has focused on creating a “learning ecosystem” rather than just deploying devices. Their approach to longitudinal measurement involves tracking “Portrait of a Graduate” attributes—skills like communication and critical thinking—which are difficult to measure via standardized tests.

- Mechanism: By using performance-based assessments and teacher portfolios over time, they track how technology supports these higher-order skills.

- Current Application: Their recent pilot with AI tools (ChatGPT) demonstrates a “Level of Use” strategy. Instead of a blanket rollout, they started with a small pilot cohort to identify “Management” concerns and “Innovation” configurations before scaling. This “go slow to go fast” approach is classic longitudinal best practice.

8.2 Case Study: Austin ISD – Strategic Scorecards

Austin ISD utilizes a “Scorecard” system to monitor strategic goals. This acts as a high-level dashboard.

- Mechanism: They align technology initiatives with broader district goals (e.g., equity, literacy). Their evaluations often use surveys (Climate Surveys, TELL Survey) to gather longitudinal data on teacher working conditions and resource availability.

- Insight: By linking tech data with “Climate” data, they acknowledge that technology integration relies on a supportive environment. If the climate score drops, they know tech adoption will likely stall.

8.3 Case Study: Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS)

MCPS conducted a study of their “21st Century Learning Spaces” initiative.

- Mechanism: They utilized a two-stage evaluation. Stage 1 examined implementation (Leading Indicator: PD attendance, device deployment). Stage 2 examined impact (Lagging Indicator: Student outcomes).

- Insight: This staged approach prevents the error of measuring impact before implementation is complete. They found that professional learning was the key variable in successful spaces.

Section IX: Conclusion and Recommendations

The measurement of long-term technology integration is a complex, multi-layered endeavor that requires a fundamental shift in perspective. It demands moving from counting “things” (devices, software logins) to mapping “people” (concerns, behaviors, pedagogical beliefs). Sustained change is a slow, developmental process often characterized by periods of regression (the “implementation dip”) before growth.

Recommendations for District Leaders and Evaluators

- 1. Adopt a Framework immediately: Do not invent home-grown metrics. Adopt CBAM or TIM to ensure your data has validity and can be compared to broader research.

- 2. Establish Cohorts: Identify a group of teachers to follow for 3 years. This “sentinel group” will provide the deepest insights into the health of your integration efforts. Use the “Teaching Square” model to drive peer-supported growth within this cohort.

- 3. Prioritize Leading Indicators: Pay more attention to “Stages of Concern” and “Levels of Use” in the first 2 years than to student test scores. If teachers are stuck at “Management” concerns, student achievement will not rise.

- 4. Democratize Data: Use simple tools like Google Sheets and Looker Studio to give teachers access to their own data. Make the tracking process transparent and developmental, not evaluative.

- 5. Invest in Qualitative Capacity: Train instructional coaches in basic interviewing (LoU protocol) and observation (TIM-O). The “why” uncovered in a 20-minute interview is often more valuable than a thousand survey responses.

- 6. Plan for the Dip: Expect the “Implementation Dip” in Year 1. Communicate this expectation to the School Board so they do not pull funding when scores temporarily flatten.

By implementing these strategies, educational organizations can move beyond the hype of the “latest tool” and foster a culture of sustained, meaningful, and transformative teaching and learning.