Reusable Tech Lesson Plans: Reduce Teacher Workload & Burnout

Scalable Instructional Design: Architecting Reusable, Tech-Integrated Curricula for Teacher Efficacy and Workload Reduction

Executive Synthesis: The Intersection of Design, Trust, and Workload

The contemporary educational landscape is navigating a precarious equilibrium between two formidable forces: the imperative for sophisticated, technology-integrated instruction and the escalating crisis of teacher workload and burnout. The integration of technology into the classroom, whether face-to-face, online, or hybrid, presents a complex matrix of opportunities and challenges that requires more than just the procurement of hardware or software licenses. It demands a fundamental reimagining of how instructional materials are designed, shared, and implemented. Research consistently indicates that high staff workloads are not merely logistical challenges to be managed through better scheduling; they are significant drivers of stress, emotional exhaustion, and attrition. Recent data reveals that workload is consistently one of the least positive areas of staff experience, with surveys showing only 33% of staff responding positively to questions regarding their workload balance.

In this context, the design of lesson plans ceases to be solely a pedagogical exercise and becomes an operational imperative for retaining talent and sustaining school improvement. Teachers trust resources—and the people who provide them—that effectively reduce their cognitive and administrative load. This “trust” is not abstract; it is built on the pillars of benevolence, reliability, and competence. When teachers are provided with high-quality, reusable, and adaptable resources that align with curriculum standards and include explicit facilitation guidance, the cognitive load associated with curriculum creation is significantly reduced. This reduction allows educators to redirect their finite energy toward the interpersonal and instructional dynamics of the classroom—the “core business” of teaching.

However, the creation of such resources is not a trivial task. It requires a systematic approach to “educative curriculum design,” where the lesson plan itself serves as a vehicle for professional learning, containing facilitator guides, reflection mechanisms, and clear technical protocols. It requires moving beyond the “static PDF” to “living documents” that facilitate co-planning and continuous iteration. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the frameworks, structural templates, co-planning methodologies, and technical architectures required to build a repository of instructional assets that are exhaustive in detail, rich in insight, and capable of reducing workload while elevating instructional rigor.

________________

Part I: The Theoretical Architectures for Technology Integration

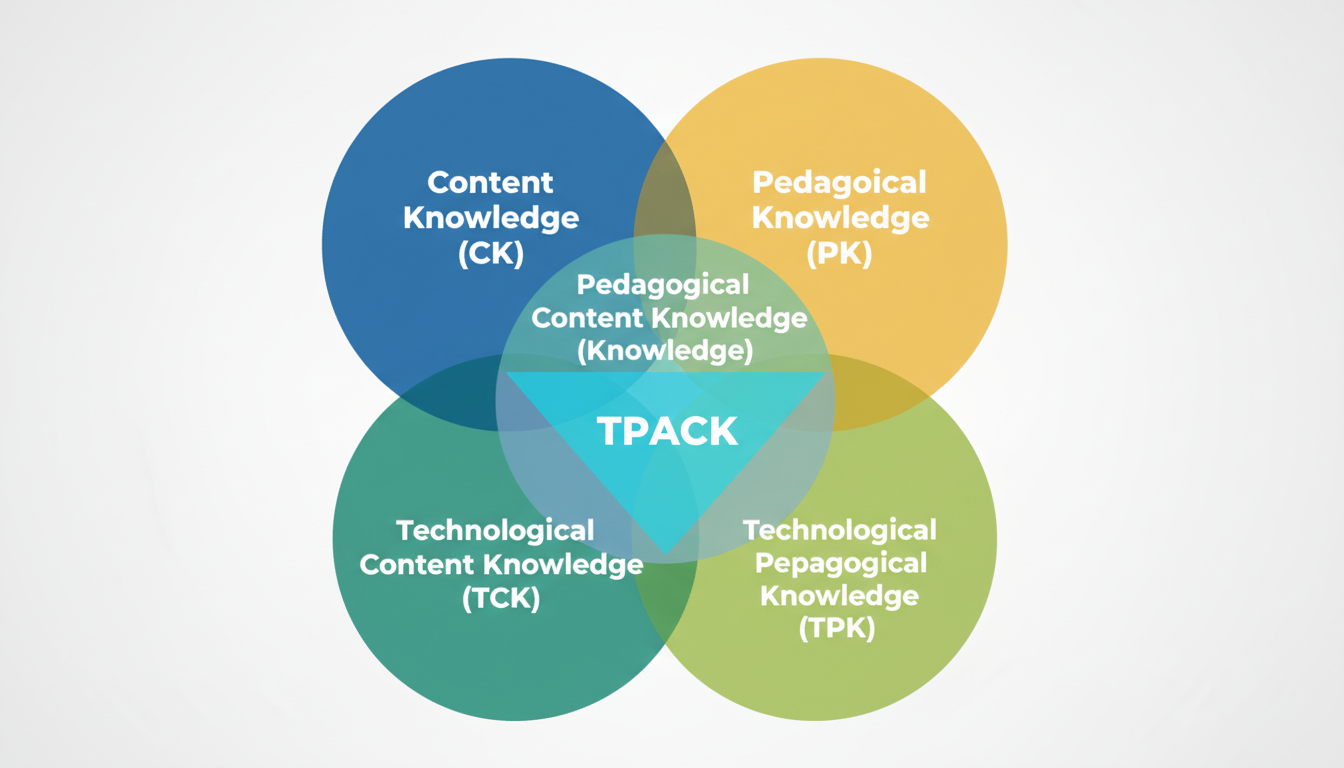

To design lesson plans that are both reusable and instructionally potent, instructional designers must ground their templates in robust theoretical frameworks. The integration of technology cannot be an additive process—simply overlaying digital tools on existing analog practices—but must be an integrative one that considers the complex interplay between content, pedagogy, and technology. Two primary models, the TPACK framework and the SAMR model, provide the necessary lexicon and conceptual scaffolding for designing templates that move beyond “digital worksheets” to truly transformative learning experiences.

1.1 The TPACK Framework: Balancing Content, Pedagogy, and Technology

The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework, first introduced by Punya Mishra and Matthew J. Koehler of Michigan State University in 2006, argues that effective technology integration occurs at the intersection of three primary knowledge domains: Content Knowledge (CK), Pedagogical Knowledge (PK), and Technological Knowledge (TK). For the design of reusable lesson plans, TPACK serves not just as a theoretical construct, but as a practical quality control mechanism.

1.1.1 The Interdependence of Domains

A reusable lesson plan that focuses heavily on a specific application (high TK) but fails to account for how students learn the specific concept (low PK) or misrepresents the subject matter (low CK) is destined to fail when transferred from the designer to another teacher. The power of the TPACK framework lies in its recognition that these domains are interdependent and of equal importance.

- Technological Knowledge (TK): This domain involves an understanding of digital tools, ranging from standard hardware like interactive whiteboards to advanced software and collaborative platforms. In the context of a reusable template, high TK manifests as explicit instructions on how to use the tool, troubleshooting guides, and alternative options if the technology fails. It requires the designer to consider digital literacy—both the teacher’s and the students’—and access to infrastructure.

- Pedagogical Knowledge (PK): This refers to the deep knowledge about the methods and processes of teaching and learning, including knowledge of classroom management, assessment, and lesson planning. Reusable plans must explicitly state the instructional strategy embedded in the technology use. Is the technology supporting inquiry-based learning? Is it facilitating direct instruction? Without this explicit pedagogical framing, the “why” of the lesson is lost.

- Content Knowledge (CK): This is the knowledge about the actual subject matter that is to be learned or taught. The technology selected must enhance the representation of this content, not obscure it. For instance, in a science lesson, a simulation tool is only valuable if it accurately models the scientific phenomenon in question.

1.1.2 TPACK as a Design Filter

When creating templates for reuse, instructional designers must use TPACK as a filter: Does this technology support the content and pedagogy, or does it distract from it? Research into ESL teachers’ use of technology suggests that many struggle with integration not because of a lack of general tech skills, but due to limited technological pedagogical knowledge—knowing how to use the tech to teach specific language concepts effectively. Therefore, a reusable lesson plan must explicitly bridge these gaps for the receiving teacher, providing the “Technological Pedagogical” glue that might otherwise be missing. This involves detailing not just which tool to use, but how that tool specifically elucidates the content at hand.

1.2 The SAMR Model: A Ladder for Depth and Transformation

While TPACK describes the knowledge required to integrate technology, the SAMR model (Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition) describes the impact of the technology on the learning task itself. Developed by Dr. Ruben Puentedura, this taxonomy is critical for evaluating whether a reusable lesson plan is worth the technical overhead required to create and share it.

1.2.1 The Enhancement Phase: Substitution and Augmentation

The first two levels of SAMR focus on enhancement.

- Substitution: At this level, technology acts as a direct tool substitute with no functional change. An example would be having students type a paper in a word processor instead of writing it by hand. While this may offer some efficiency, reusable plans at this level often do not justify the effort of complex template creation unless they offer significant workflow automation. The lesson design is fundamentally unchanged.

- Augmentation: Here, technology acts as a direct substitute but with functional improvement. An example includes using a Google Doc that offers spell check, grammar suggestions, and voice typing. This adds value, but the core task remains the same.

1.2.2 The Transformation Phase: Modification and Redefinition

For a lesson plan to be highly valuable as a shared resource—and to truly justify the “workload reduction” claim—it ideally targets the transformation levels. In these stages, the labor saved by sharing the plan is highest because the instructional design is inherently more complex and difficult for a single teacher to produce in isolation.

- Modification: Technology allows for significant task redesign. An example might be a social studies lesson where students collaborate on a shared document to write a policy paper, providing real-time peer feedback and integrating multimedia evidence. The task is fundamentally altered by the collaborative affordances of the technology.

- Redefinition: This is the pinnacle of the model, where technology allows for the creation of new tasks, previously inconceivable. An example would be connecting with a classroom in another country for a cultural exchange via video conference or having students create a virtual reality tour of a historical site.

Table 1: The SAMR Model and Reusable Template Implications

| SAMR Level | Definition | Reusable Template Implication | Workload Impact for Reuser |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substitution | Tech acts as a direct substitute, no functional change. | Low Value Reuse: Simple digitizing of worksheets. |

Augmentation

Tech acts as a direct substitute, functional improvement.

Moderate Value Reuse: Templates that auto-grade (e.g., Google Forms) or provide instant feedback mechanisms.

Moderate; saves grading time and enhances feedback speed.

Modification

Tech allows for significant task redesign.

High Value Reuse: Collaborative workspaces, project management boards (Trello/Notion), dynamic presentations.

High; provides complex structures the teacher would struggle to build alone.

Redefinition

Tech allows for new tasks, previously inconceivable.

Highest Value Reuse: VR expedition guides, global collaboration protocols, multimedia production kits.

Very High; unlocks entirely new pedagogical possibilities without the design burden.

1.3 Aligning Frameworks with Standards (ISTE & Common Core)

To ensure reusable plans are trusted and utilized across different districts and contexts, they must align with established standards. The ISTE Standards for Students emphasize empowering the learner, which aligns well with the “Apply” and “Share” phases of modern lesson design.

- Interoperability of Standards: A reusable lesson plan should map the technology activity (ISTE) to the content standard (Common Core/State Standards). For example, a lesson on “Analyzing Point of View” (CCSS ELA) can be paired with “Creative Communicator” (ISTE) by having students create a digital story from a character’s perspective. This dual coding ensures that the technology is seen as a vehicle for achieving rigorous content goals, rather than an add-on.

- Practical Application: When designing the template, metadata fields must be included for these standards. This allows teachers to search repositories by standard, increasing the discoverability and utility of the resource. The ISTE standards explicitly call for lesson designs that include “purposeful use of technology,” and aligning plans in this way helps districts meet their systemwide technology goals.

Part II: The Anatomy of a Reusable Tech-Integrated Lesson

A common failure mode in lesson sharing is the distribution of the student-facing document (the worksheet, the slide deck) without the teacher-facing context (the strategy, the pacing, the “gotchas”). A truly reusable resource functions as an an “educative curriculum,” helping the teacher learn the pedagogy while executing the lesson. The following components are essential for a comprehensive, reusable design.

2.1 The Facilitator Guide: The “Missing Link”

Research into effective professional development and curriculum scaling highlights the necessity of a “Facilitator Guide” or “Implementation Guide”. This document serves as the “brain” of the lesson, containing the tacit knowledge the original designer possesses but which is often lost in transfer.

2.1.1 Pedagogical Rationale and Trust Building

The facilitator guide must explain why specific choices were made. Why was this specific tech tool chosen? How does it serve the learning objective? This transparency builds “Competence Trust” with the receiving teacher—assurance that the designer knows what they are doing. It transforms the resource from a set of instructions into a professional learning tool.

2.1.2 Pacing and Logistics

Detailed timelines are crucial for novice teachers or those new to a specific technology. Guides should break down the lesson into manageable chunks (e.g., “0:00-0:10: Introduction,” “0:10-0:30: Exploration”). This granularity helps teachers manage the classroom flow and ensures that technology use does not consume the entire period at the expense of content.

2.1.3 Troubleshooting and Alternatives

Technology is inherently fallible. A high-quality facilitator guide acts as a safety net by asking and answering: “What if the internet goes down?” “What if the app is blocked?” Providing analog backups or alternative digital tools is a hallmark of “Benevolence Trust”—showing the designer cares about the user’s success and has anticipated potential points of failure.

2.1.4 Differentiation Protocols

To be truly reusable, a plan must work for diverse learners. The guide should include explicit guidance on how to modify the digital content for Special Education (SPED) or English Language Learners (ELL). This might include links to text-to-speech extensions, alternative simplified reading passages, or specific grouping strategies. OpenSciEd units, for instance, include specific “differentiation callouts” in their teacher guides, offering strategies for both support and extension.

2.2 The Student Interface (The “HyperDoc” or “Playlist”)

The student-facing component must be distinct from the facilitator guide. This is the digital workspace where the learner interacts with the content.

- Visual Clarity: The design must reduce cognitive load. Use of icons, consistent color coding, and clear headers (e.g., “Watch,” “Read,” “Do”) helps students navigate the resource independently.

- Embedded Choice: Reusable plans should include “Must Do” and “May Do” sections. This structure allows the receiving teacher to adjust the rigor or length of the lesson without breaking the core sequence. It empowers students to take ownership of their learning path.

- Force-Copy Mechanisms: To prevent students (or other teachers) from altering the master template, links should be modified to force a unique copy. This is typically achieved by changing the end of a Google Drive URL from /edit to /copy. This simple technical hack is vital for the integrity of shared resources.

2.3 The Reflection and Feedback Loop

For a lesson plan to evolve, it must include a mechanism for reflection. This transforms a static document into a living resource that improves over time.

- Teacher Reflection Section: A dedicated space in the facilitator guide for the teacher to record: “What went well?”, “Student misconceptions,” and “Tech glitches”. This prompts metacognition and helps the teacher internalize the lesson’s success and failure points.

- Iterative Design Notes: A “Notes for Future Teachers” section allows collaborative teams to leave breadcrumbs for one another. For example, a note might read, “Students struggled with the login process for this app; recommend doing a demo first.” This fosters a culture of continuous improvement and collective efficacy.

Part III: Structural Models for Digital Lesson Delivery

Different pedagogical goals require different structural templates. A “one-size-fits-all” lesson plan does not work for tech integration. Below are detailed analyses of four distinct architectures for reusable planning: The HyperDoc, The 5E Model, The Playlist, and the Educative Facilitator Guide.

3.1 The HyperDoc Model: Explore, Explain, Apply

HyperDocs are interactive digital lesson plans—usually built in Google Docs or Slides—that guide students through a learning cycle. They are highly reusable because they package content, instruction, and assessment into a single link. They are not merely digital worksheets; they are “transformative, interactive Google Docs” that replace the lecture-and-worksheet method.

3.1.1 The Framework

The core structure of a HyperDoc often follows the “Explore-Explain-Apply” cycle:

- Explore: In this phase, students engage with multimedia resources (videos, VR tours, articles) to build background knowledge before direct instruction. This flips the traditional model, shifting the teacher’s role from lecturer to facilitator. Resources might include a Wakelet collection or a ThingLink interactive image.

- Explain: Here, the teacher (or a curated video/text resource) clarifies concepts and addresses misconceptions identified during the exploration phase. This is the “direct instruction” component, but it is targeted and responsive. Tools like Screencastify or EdPuzzle are often used here to deliver content asynchronously.

- Apply: Students demonstrate understanding by creating a digital artifact—such as a video, infographic, or podcast—rather than simply answering multiple-choice questions. This is where the lesson reaches the “Modification” or “Redefinition” levels of SAMR.

3.1.2 Best Practices for Reuse

- Template Standardization: Using a consistent “Explore-Explain-Apply” header structure makes it easy for students to navigate different lessons and for teachers to design them.

- Multimedia Text Sets: Grouping links into “text sets” allows teachers to easily swap out a broken link or outdated article without redesigning the entire lesson structure.

- Design Aesthetics: HyperDocs rely on “packaging” to engage students. The use of color, tables, and clear fonts helps students navigate the document. Templates often include sections for “Engage,” “Explore,” “Explain,” “Apply,” “Share,” “Reflect,” and “Extend”.

3.2 The 5E Instructional Model in Technology

Widely used in science education and notably adopted by OpenSciEd, the 5E model provides a rigorous structure for inquiry-based learning. It is particularly effective for lessons that require students to construct their own understanding from evidence.

3.2.1 The Phases

- Engage: This phase captures interest and elicits prior knowledge, often through a “discrepant event” or phenomenon. Digital tools like short video clips or intriguing images are powerful here.

- Explore: Students actively investigate the phenomenon. This might involve digital simulations (e.g., PhET), data collection with sensors, or online research. The key is that students are doing science, not just reading about it.

- Explain: Students verbalize their understanding, and the teacher introduces formal vocabulary and concepts to connect their experiences to scientific principles.

- Elaborate: Students apply their new knowledge to different contexts or related problems.

This deepens understanding and facilitates transfer of learning.

5. Evaluate: This involves both formative and summative assessment of student learning. Digital tools like Google Forms, Quizizz, or digital portfolios are often used here.

3.2.2 Tech Integration in 5E

- Digital Phenomena: The “Engage” phase can utilize high-quality video or simulations to present phenomena that are impossible or dangerous to replicate in a physical classroom.

- Data Collection: The “Explore” phase can leverage digital sensors or collaborative spreadsheets for class-wide data aggregation and analysis, allowing for “Modification” level tasks.

3.3 The Playlist / Choice Board Model

This model is essential for differentiation and student agency. It presents a menu of learning options, often structured as “Must Do” (required) and “May Do” (extension) tasks. It allows for asynchronous learning and frees the teacher to work with small groups.

3.3.1 Structural Variations

- Linear Playlist: A sequential list of tasks (1, 2, 3) where students move at their own pace. This scaffolds learners from introduction to practice to mastery.

- Tic-Tac-Toe / Bingo Board: A grid where students choose a row or column of activities to complete. This ensures they hit necessary modalities (e.g., one reading task, one watching task, one creating task) while retaining choice.

- Must Do / May Do: A split list that prioritizes core standards (“Must Do”) while offering enrichment or choice activities (“May Do”) for fast finishers. This is excellent for managing diverse pacing in a classroom.

3.3.2 Reusability Factors

- Modularity: Choice boards are highly reusable because individual squares can be updated without scrapping the whole board. If a link breaks, only one option needs to be replaced.

- Student Autonomy: These models free up the teacher to work with small groups, effectively reducing the active instructional load during the class period. This shift from “sage on the stage” to “guide on the side” is a key element of workload reduction.

3.4 The “Educative” Facilitator Guide Template

Drawing from the OpenSciEd and professional development literature, a robust facilitator guide template should accompany the digital student resources to ensure implementation fidelity and teacher confidence.

Table 2: Facilitator Guide Template Structure

- Lesson Metadata

- Title, Grade, Subject, Standards (ISTE/CCSS), Estimated Time. Helps with cataloging and searchability.

- Preparation Checklist

- “Print X,” “Charge devices,” “Pre-load URLs,” “Check firewalls.” Reduces anxiety by making prep concrete.

- Instructional Sequence

- A scripted flow: Time Chunk (e.g., 10 mins) -> Teacher Move (e.g., “Launch the Anchoring Phenomenon video”) -> Student Action (e.g., “Record observations in digital notebook”) -> Differentiation Note (e.g., “Turn on captions for ELLs”).

- Key Discussion Questions

- Scripted higher-order thinking questions to guide discourse. Includes probing questions to deepen thinking.

- Assessment Look-fors

- What specific evidence of learning should the teacher observe? Helps the teacher focus their attention during the lesson.

Part IV: The Co-Planning Engine: Protocols, Scripts, and Coaching

The creation of these resources should not be a solitary endeavor. “Co-planning” is the engine that drives the quality and trust required for adoption. Research confirms that collaboration reduces isolation, improves efficacy, and builds the relational trust necessary for sharing work. Effective co-planning transforms lesson design from a chore into a professional learning experience.

4.1 The Role of the Instructional Coach

Instructional coaches play a pivotal role in this ecosystem. They are often the “architects” who build the master templates and facilitate the co-planning process. To build trust, coaches must demonstrate benevolence (caring about the teacher’s time and well-being), reliability (following through on promises), and competence (knowing the pedagogy and the tech).

4.1.1 The Co-Planning Cycle

- The Kick-Off Meeting: This is not just about logistics; it is about building a partnership. The coach should use a script or protocol to establish rapport. Questions might include: “What is your goal for this lesson?” “What are your fears about the tech?” “How can I reduce your workload today?”. This initial conversation sets the tone for a collaborative relationship.

- The Design Phase: The coach and teacher co-construct the lesson. The coach might handle the technical build (the “heavy lifting” of formatting the HyperDoc), while the teacher focuses on content rigor. This division of labor actively reduces the teacher’s workload and builds trust through service.

- The Implementation: The coach acts as a co-teacher or “tech support” during the lesson delivery. This reduces the risk of failure for the teacher—if the tech fails, the coach is there to fix it. This “in-the-trenches” support is crucial for building teacher confidence.

- The Reflection: A post-lesson debrief is essential. The coach and teacher analyze student work and discuss what worked and what didn’t. This reflection informs the revision of the template for future use.

4.2 Probing Questions for Deepening Design

To move teachers from “Substitution” to “Redefinition” in the SAMR model, coaches must use strategic questioning during the planning phase. These questions push the teacher to think deeper about the purpose of the technology.

- Metacognition: “How will this technology empower students to control their own learning?” “What questions do I still have about this topic?”.

- Depth: “Does the technology allow for the creation of a new task previously inconceivable?” “How might you use this tool to allow students to present to an authentic audience?”.

- Differentiation: “How can we use this tool to support students who struggle with reading/writing?” “Are there workarounds or supports we might consider to help them access the learning process?”.

4.3 Co-Planning Protocols

Effective co-planning requires structure to be efficient. Protocols ensure that time is used effectively (respecting the teacher’s limited time) and that all pedagogical bases are covered.

- The “Agenda Questions” Protocol: A checklist of questions regarding student needs, logistics, roles, and assessment data that guides the planning meeting. Questions include: “What are our expectations for this partnership?” “Who teaches what in the lessons?” “What plans might we have for classroom management?”.

- The “Scope and Sequence” Review: This involves ensuring the specific lesson fits into the broader unit trajectory and aligns with the long-term curriculum goals. This prevents the lesson from being a “one-off” activity unrelated to the broader learning arc.

Part V: Technical Infrastructures for Sharing and Remixing

For lesson plans to be truly reusable, they must be technically accessible and editable. A PDF is a “dead” document; a Google Doc with a “Force Copy” link is a living tool. The technical architecture must support the “5 Rs” of OER: Retain, Reuse, Revise, Remix, and Redistribute.

5.1 The Google Workspace Ecosystem

Google Workspace provides a robust platform for creating and sharing editable resources.

- Force Copy Hack: This is a critical technique for sharing templates. By changing the end of a Google Doc/Slide URL from /edit to /copy, the user is forced to make a copy to their own drive before seeing the document. This protects the master template from accidental edits while ensuring every teacher gets a fresh version to modify.

- Template Gallery: Districts can set up a “Template Gallery” within their Google domain. This allows teachers to submit and retrieve approved templates for docs, slides, and sheets, ensuring consistency across the organization.

- Placeholder Chips: New features in Google Docs allow for “variable chips” or placeholders. Teachers can create templates with smart chips for “Date,” “Student Name,” or “Instructions,” allowing users to quickly plug in specific information without breaking the formatting.

5.2 Learning Management Systems (Canvas/Schoology)

LMS platforms offer built-in repositories for sharing curriculum.

- Canvas Commons: This is a repository within Canvas where teachers can share modules, quizzes, assignments, or entire courses. Resources can be shared publicly, or restricted to a specific district or group. This integration allows teachers to import content directly into their courses with a few clicks.

- Blueprint Courses: Administrators can create a “Blueprint” course that pushes updates to all associated teacher courses. This is powerful for ensuring baseline curriculum fidelity while allowing for local adaptation. Teachers can add to the blueprint but cannot delete locked content.

5.3 Emerging Tools: Notion and Databases

Tools like Notion are emerging as powerful platforms for curriculum management due to their database capabilities.

- Notion for Education: Notion offers sophisticated databases that can link lesson plans to standards, resources, and student rosters. Its “template” button feature allows for infinite replication of lesson structures. Teachers can build a “Teacher OS” that tracks everything from lesson plans to student progress in one interconnected workspace.

Part VI: Legal and Ethical Frameworks for Sharing (OER)

Scaling reusable lesson plans requires a clear understanding of intellectual property. Open Educational Resources (OER) provide the legal framework for sharing and collaboration.

6.1 The “5 Rs” of OER

True OER allows users to engage in the “5 Rs”:

- Retain: Make, own, and control copies of the content.

- Reuse: Use the content in a wide range of ways.

- Revise: Adapt, modify, and improve the content (critical for localization and differentiation).

- 4.

Remix: Combine the original or revised content with other material to create something new.

5. Redistribute: Share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others.

6.2 Creative Commons Licensing

Teachers and districts should apply Creative Commons licenses to their work to clarify permissions and facilitate sharing.

- CC BY (Attribution): This license allows others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as they credit the original creation. This is the most accommodating of licenses.

- CC BY-NC (Non-Commercial): This license allows others to remix, adapt, and build upon the work non-commercially. Their new works must also be non-commercial and acknowledge the original author.

- CC BY-SA (ShareAlike): This license requires remixes to be shared under the same license terms. This “viral” openness ensures that improvements to the resource remain open to the community.

Best Practice: Facilitator guides and student resources should clearly state the license type in the footer, ensuring downstream users know their rights and responsibilities. This transparency builds trust and encourages legal sharing.

Part VII: Case Studies in Systemic Implementation

Theoretical models are validated by real-world application. The following case studies demonstrate how districts and organizations have successfully implemented collaborative, reusable curriculum models to improve teacher efficacy and student learning.

7.1 Vista Unified School District (California)

Vista Unified implemented a “Personal Learning Star” model emphasizing collaboration and trust. They utilized the “COW Project” (California-Ohio-Wisconsin) to collaborate inter-district on OER resources.

- Success Factor: A focus on “trust, kindness, and respect” as foundational to the vision. They recognized that collaboration requires a culture of safety.

- Strategy: They leveraged OER to create opportunities for student collaboration across state lines, which required teachers to first collaborate on curriculum design. This “inter-district” collaboration forced the creation of universally understandable and reusable plans.

- Impact: The initiative shifted the culture from isolation to collective efficacy, with teachers reporting higher satisfaction and students engaging in deeper learning experiences.

7.2 Kettle Moraine School District (Wisconsin)

This district is noted for its personalized learning environments and innovative micro-credentialing for teachers.

- Success Factor: Teachers were empowered to earn micro-credentials (competency-based PD) for designing and implementing specific instructional strategies. This aligned professional growth with curriculum development.

- Strategy: Collaborative planning was incentivized and structured. Resources were designed to be shared and iterated upon. The district focused on eliminating boundaries and providing resources so every teacher has the support needed to inspire.

- Impact: The district has seen high teacher retention and consistently “significantly exceeds expectations” on district report cards. The focus on micro-credentials has also led to salary increases for teachers, directly linking competence to compensation.

7.3 OpenSciEd (National)

OpenSciEd represents the gold standard in “educative curriculum.” It is a national initiative to create high-quality, open-source science curriculum.

- Strategy: They provide comprehensive Teacher Handbooks, slide decks, and student materials that are OER. These materials are designed to be “educative”—teaching the teacher how to teach the unit.

- Design: Every unit includes “Teacher Background Knowledge,” “differentiation callouts,” and specific “routines” (e.g., Anchoring Phenomenon Routine, Navigation Routine). The materials explicitly guide the teacher through the inquiry process.

- Impact: It reduces the burden of planning complex NGSS-aligned lessons while providing high-quality PD embedded in the materials. Teachers can trust the quality because it is backed by a consortium of states and rigorous field testing.

Part VIII: Overcoming Barriers to Adoption

Despite the clear benefits of reusable lesson plans, barriers to adoption exist. Research identifies “internal barriers” (beliefs, self-efficacy) and “external barriers” (time, access, resources). Addressing these is crucial for the success of any sharing initiative.

8.1 The “Not Invented Here” Syndrome

Teachers often resist using plans they didn’t create because they feel the plans don’t match their specific students’ needs or their personal teaching style.

- Solution: Design for adaptability (Remix), not just adoption. Templates must be editable (Google Docs vs. PDFs). Facilitator guides must explain the why so teachers can modify the how intelligently without breaking the lesson’s core logic. The “remix” culture of OER directly addresses this by inviting modification.

8.2 The “Context Gap”

A lesson plan that works in a high-tech suburban school with 1:1 devices may fail in a rural school with limited bandwidth or older hardware.

- Solution: Include “Low-Tech” alternatives in the Facilitator Guide. Explicitly list the necessary prerequisites (e.g., “Students need Google Accounts,” “Requires reliable WiFi”). Providing these alternatives demonstrates “Benevolence Trust” and inclusivity.

8.3 The “Static Document” Problem

Lesson plans often become outdated as links rot, tools change, or standards evolve. A static PDF is a snapshot in time that degrades in value.

- Solution: Use “Living Documents” (e.g., Google Docs, Notion, Canvas Commons) rather than static files. Encourage a culture of “versioning” where teachers upload their improved versions back to the repository (Remixing). This turns the repository into a dynamic, evolving ecosystem rather than a dusty archive.

Part IX: Conclusion and Strategic Recommendations

The creation of reusable, tech-integrated lesson plans is a high-leverage strategy for improving instruction and reducing teacher burnout. It moves the profession away from the “hero teacher” model—where every individual must invent their own curriculum from scratch—toward a model of collective efficacy and shared wisdom. However, success requires a shift from viewing lesson plans as administrative compliance documents to viewing them as “instructional assets” or “software code” that can be shared, forked, and improved.

Strategic Recommendations for Educational Leaders:

- Invest in “Educative” Templates: Move beyond the standard lesson plan box. Adopt comprehensive templates that include Facilitator Guides, Differentiation Protocols, and Reflection Logs. These templates should be the standard for the district.

- Formalize Co-Planning: Allocate specific time and personnel (instructional coaches) to support the design process. Use protocols to ensure this time is productive and focused on design, not just logistics.

- Build the Infrastructure: Establish a central repository (Google Team Drives, Canvas Commons) with clear naming conventions and tagging (ISTE/CCSS standards) to ensure discoverability.

- Cultivate Trust: Recognize that sharing work requires vulnerability. Celebrate “remixing” as a form of innovation, not plagiarism. Focus on “Benevolence” and “Competence” in coaching relationships to build the psychological safety needed for sharing.

- Prioritize OER: Adopt Open Educational Resources to ensure legal flexibility and cost savings. Use the savings to fund professional development and co-planning time.

By treating lesson planning as a collaborative, design-based engineering challenge rather than a solitary artistic endeavor, schools can build a sustainable ecosystem where technology truly enhances learning, and teachers are supported, empowered, and—most importantly—retained.

Appendix A: Reusable Lesson Plan Template (Example Structure)

Note: This structure is synthesized from the research on HyperDocs, 5E, and Facilitator Guides.

I. Facilitator Guide (Teacher Facing)

Section

Details

Title & Metadata

[Lesson Name]

Standards

- Content:

- Tech:

Learning Objectives

“Students will be able to…” (SWBAT)

Tech Stack

- Hardware: [Chromebooks/iPads]

- Software: [Apps/Links]

- Backups:

Preparation Checklist

- [ ] Copy Google Slides to Drive

- [ ] Create Flipgrid Topic

- [ ] Print Graphic Organizer for SPED students

Differentiation

- ELL:

- SPED:

- Extension:

II. Instructional Sequence (The “Script”)

Time: 0-10

Phase (5E/HyperDoc): Engage

Teacher Action: Show “Anchoring Phenomenon” video. Ask driving question.

Student Action: Watch video. Post questions to Padlet.

Formative Check: Check Padlet for prior knowledge.

Time: 10-30

Phase (5E/HyperDoc): Explore

Teacher Action: Circulate. Troubleshoot tech. Ask probing questions from guide.

Student Action: Navigate HyperDoc “Explore” links. Complete data table.

Formative Check: Observation of student screens.

Time: 30-50

Phase (5E/HyperDoc): Explain

Teacher Action: Facilitate discussion on findings. Clarify vocab.

Student Action: Share findings. Take notes.

Formative Check: “Fist to Five” check for understanding.

Time: 50-60

Phase (5E/HyperDoc): Apply/Evaluate

Teacher Action: Assign “Create” task.

Student Action: Begin drafting digital artifact.

Formative Check: Exit Ticket (Google Form).

III. Reflection & Iteration (Post-Lesson)

- What worked well?

- What failed?

- Changes for next time: