Teacher Tech Resistance: Empathy, Support & Digital Agency

Executive Overview: Dismantling the Myth of the Luddite

Table of Contents

- Executive Overview: Dismantling the Myth of the Luddite

- Part I: Theoretical Frameworks of Acceptance and Resistance

- ↳ 1.1 The Evolution of Acceptance: From TAM to UTAUT

- ↳ 1.2 The Competence Crisis: The TPACK Framework

- ↳ 1.3 Behavioral Intention and the “Sins of Omission”

- Part II: The Ecology of Beliefs – Pedagogical Conflicts and Cognitive Defense

- ↳ 2.1 The Conflict of Cognitive Depth: Deep Reading vs. Digital Skimming

- ↳ The Loss of Critical Analysis

- 2.2 The Motor-Cognitive Connection: Handwriting vs. Typing

- ↳ The “Reading Circuit” Activation

- 2.3 Philosophical Resistance: Montessori and Waldorf Perspectives

- ↳ Montessori: The Concrete before the Abstract

- ↳ Waldorf: Protecting the Human Connection

- 2.4 The Erosion of Empathy and Social Interaction

- ↳ Table 2: Cognitive and Pedagogical Conflicts

- Part III: The Psychology of the Teacher – Fear, Identity, and Burnout

- ↳ 3.1 The Spectrum of Fear: Incompetence and Obsolescence

- ↳ 3.2 Technostress: Overload and Invasion

- ↳ 3.3 The Veteran Teacher Paradox

- Part IV: Institutional Failures – The Ecology of Pressure

- 4.1 Top-Down Mandates and the Loss of Autonomy

- ↳ The Disconnect of Decision Making

- ↳ Coercive Isomorphism

- 4.2 Infrastructure and Reliability Friction

- ↳ Table 3: Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Implementation Impacts

- Part V: Strategic Frameworks for Support – From Coercion to Empathetic Leadership

- ↳ 5.1 The “Warm Demander” Leader

- ↳ 5.2 Building Psychological Safety: The “Sandbox” Approach

- ↳ 5.3 Instructional Coaching as Partnership

- ↳ 5.4 Bottom-Up Professional Development: Edcamps

- ↳ 5.5 Reducing Friction: The Principal as Buffer

- ↳ 5.6 Addressing the AI Elephant: From Policing to Literacy

- Detailed Analysis and Strategic Recommendations

- ↳ 6.1 The Friction Audit Checklist

- ↳ 6.2 Scripts for Empathetic Leadership

- ↳ 6.3 Designing the “Sandbox” PD

- Conclusion: Reframing Resistance as Engagement

- ↳ Key Takeaways

- ↳ Final Thought:

The narrative surrounding technology integration in education has historically been framed through a binary lens: the inevitability of digital progress versus the obstinance of traditional instruction. This reductive dichotomy often characterizes the resistant teacher as a “Luddite”—a barrier to modernization who clings to the past out of fear or ignorance. However, a comprehensive analysis of the research suggests that resistance is rarely a simple refusal to modernize. Instead, it is a complex, multifaceted “ecology of reluctance” rooted in deeply held pedagogical beliefs, legitimate cognitive concerns, psychological vulnerability, and systemic institutional failures.

Resistance, when viewed through an empathetic lens, often acts as a protective mechanism—a form of quality control where educators defend the cognitive architecture of their students against the perceived shallowness of digital engagement. Whether it is the conflict between “deep reading” and digital skimming, the neurological superiority of handwriting over typing, or the philosophical objections of Montessori and Waldorf pedagogies, teacher resistance is frequently grounded in a nuanced understanding of human development rather than a rejection of tools.

Furthermore, the psychological toll of “technostress”—the anxiety arising from constant connectivity and the fear of professional obsolescence in the age of Artificial Intelligence—cannot be overstated. Teachers are not merely resisting hardware; they are resisting the “techno-invasion” that eroding the boundaries of their professional lives and the “techno-overload” that depletes their cognitive resources.

This report posits that sustainable technology adoption cannot be achieved through top-down coercion or compliance mandates, which research indicates often exacerbate morale issues and reduce autonomy. Instead, successful integration requires a paradigm shift toward “Empathetic Leadership” and “Warm Demander” pedagogy applied to adult learning. By establishing psychological safety, creating “sandboxes” for risk-free experimentation, and utilizing partnership-based instructional coaching models, educational leaders can support teachers in cultivating “digital agency.” The path forward lies not in forcing change, but in removing the friction that makes change difficult, respecting the teacher’s role as the primary architect of the learning experience.

Part I: Theoretical Frameworks of Acceptance and Resistance

To understand the mechanics of teacher resistance, one must first engage with the established theoretical frameworks that explain how human beings accept or reject new technologies. The literature provides several robust models—specifically the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), and the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework—that mathematically and qualitatively predict teacher behavior.

1.1 The Evolution of Acceptance: From TAM to UTAUT

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), originally developed by Davis in 1989, posits that two primary factors determine whether a user will adopt a technology: Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU). In the educational context, this means a teacher will only adopt a tool if they believe it will enhance their job performance (usefulness) and if using it will be free of effort (ease of use).

However, research suggests that TAM is often insufficient for the complex environment of a school. Consequently, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) was developed to include broader social and environmental variables. The UTAUT model identifies four key determinants of behavioral intention:

- Performance Expectancy: The degree to which the teacher believes the tech will help them attain gains in job performance. If a veteran teacher believes their current analog methods yield better student outcomes, performance expectancy for the new tech is low, leading to resistance.

- Effort Expectancy: The degree of ease associated with the use of the system. This is critical in education, where time is a scarce resource. If a Learning Management System (LMS) requires ten clicks to enter a grade, the high effort expectancy guarantees resistance.

- Social Influence: The degree to which the teacher perceives that important others (principals, colleagues) believe they should use the new system. While this can drive adoption, it can also create “compliance” rather than “commitment” if the influence is perceived as coercive pressure.

- Facilitating Conditions: The degree to which the teacher believes that an organizational and technical infrastructure exists to support use of the system. This includes reliable Wi-Fi, available devices, and technical support.

Insight: Resistance is often a rational calculation within the UTAUT framework. If a teacher perceives that the Effort Expectancy is high (it’s hard to use) and the Facilitating Conditions are low (the internet is broken), rejecting the technology is the logical choice to preserve instructional time.

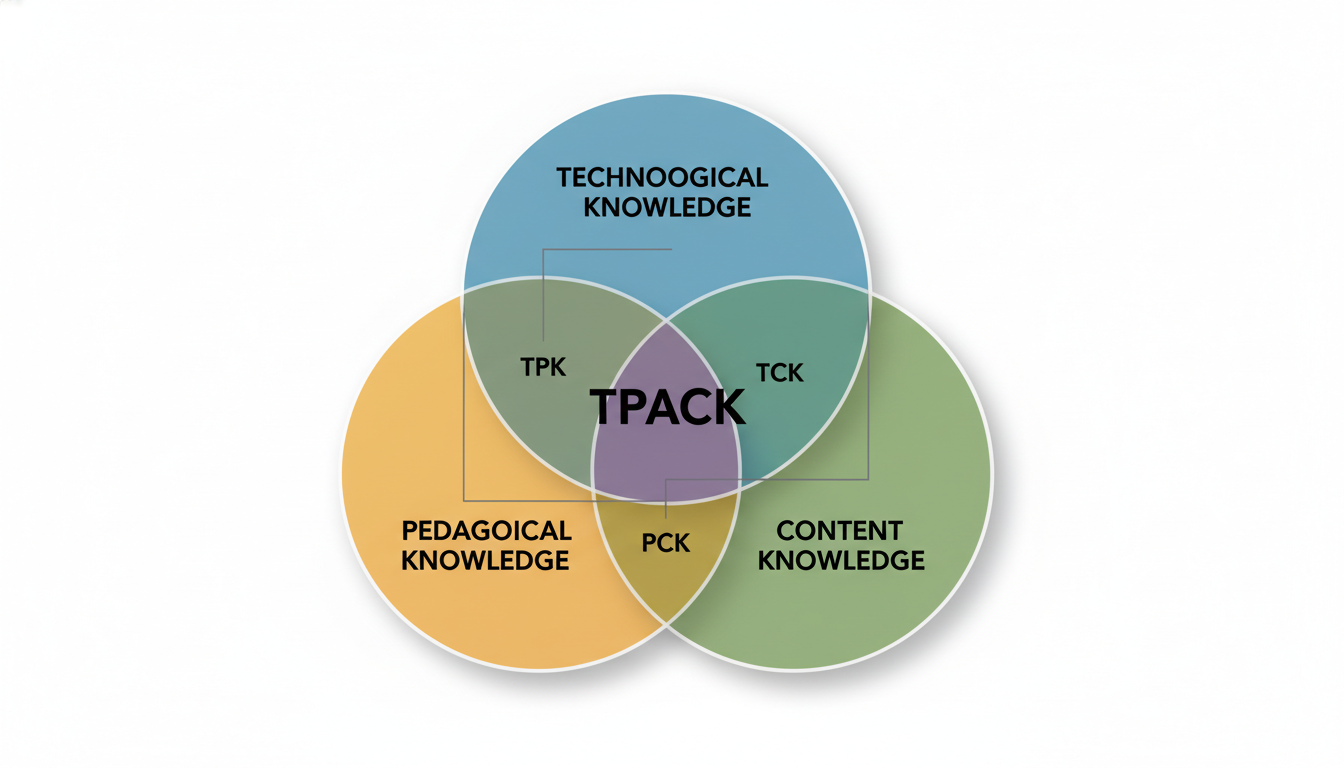

1.2 The Competence Crisis: The TPACK Framework

While TAM and UTAUT focus on the technology, the TPACK framework focuses on the teacher. TPACK (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge) describes the complex interplay between three forms of knowledge:

- Content Knowledge (CK): Knowing the subject matter (e.g., Mathematics).

- Pedagogical Knowledge (PK): Knowing how to teach (e.g., Classroom management, instructional strategies).

- Technological Knowledge (TK): Knowing how to use digital tools.

True integration occurs at the center, or TPACK, where a teacher knows how to use a specific technology to teach a specific concept effectively. Resistance often arises when a teacher has high Content and Pedagogical knowledge but low Technological knowledge. This imbalance creates a crisis of confidence. A teacher who is an expert in their field (High CK) and an expert instructor (High PK) may feel like a novice when technology is introduced (Low TK). To protect their professional identity and the quality of instruction, they retreat to the methods where they feel competent.

Research indicates that teachers with different backgrounds construct TPACK differently. Veteran teachers, for instance, may struggle to integrate new “Technological Knowledge” into their solidified “Pedagogical Content Knowledge,” whereas newer teachers may have the Tech knowledge but lack the pedagogical depth to use it effectively.

1.3 Behavioral Intention and the “Sins of Omission”

The transition from “intent” to “action” is where many technology initiatives fail. UNESCO reports highlight that the “origin story” of technology in education is often a replay of “sins of omission,” including the failure to plan, create standards, and enact policies that guide integration.

When “Facilitating Conditions” are absent—such as a lack of high-quality professional development—teachers report feeling abandoned. One teacher noted during the pandemic: “No one knew how to teach online… I was stressed because I didn’t know how to teach online… I never had a course on how to teach with technology”. This lack of preparedness reduces “Digital Agency,” the combination of competence, confidence, and accountability, leading to a defensive posture against new tools.

Table 1: Theoretical Drivers of Resistance

| Framework | Key Construct driving Resistance | Educational Context / Teacher Perception |

|---|---|---|

| TAM | Perceived Usefulness (PU) | “This app doesn’t actually help my students learn algebra better than my whiteboard.” |

| TAM | Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) | “It takes 15 minutes to set up the login for a 20-minute activity. It’s not worth the time.” |

| UTAUT | Facilitating Conditions | “The Wi-Fi drops every time 30 students try to log on. I can’t rely on this.” |

| UTAUT | Social Influence (Coercive) | “The district is forcing this on us to look modern, not because it’s good for kids.” |

| TPACK | Technological Knowledge (TK) | “I am a master English teacher, but I feel incompetent when I can’t troubleshoot the software.” |

Part II: The Ecology of Beliefs – Pedagogical Conflicts and Cognitive Defense

To dismiss resistance as merely “fear of the new” is to ignore the deep pedagogical and cognitive arguments that many teachers rely upon. Resistance is often an intellectual stance, grounded in a desire to protect the cognitive development of the student from the perceived harms of the digital medium.

2.1 The Conflict of Cognitive Depth: Deep Reading vs. Digital Skimming

A primary source of resistance among humanities and literacy teachers stems from the observation that digital mediums foster superficial engagement with text. This is not merely anecdotal; it is supported by research into the “reading brain.”

The “Shallows” Hypothesis and Cognitive Impatience

Maryanne Wolf, a leading scholar on literacy, argues that the medium of instruction profoundly alters information processing.

The digital environment, characterized by hyperlinks, notifications, and scrolling, fosters “cognitive impatience”. Teachers observe that students accustomed to screens struggle to navigate complex, linear texts or sustain attention for long-form narratives.

The resistance here is a defense of “Deep Reading”—the slow, immersive engagement that allows for empathy, critical thought, and original insight to blossom. Teachers fear that if children develop their reading circuits primarily on screens, they may never fully develop the capacity for these “slow processes”. As Wolf notes, “skimming and scanning,” which are necessary defense mechanisms for handling digital information volume, become the default mode of reading, even when the student is presented with print.

The Loss of Critical Analysis

Research indicates that digital screen use may cause downstream effects on reading comprehension, particularly for complex thought and argument. Teachers report that students are increasingly unable to engage in critical analysis sufficient to comprehend the complexity of literature or scientific texts. When a teacher bans laptops during a novel study, they are often attempting to force the brain into a different, deeper mode of processing that they believe technology actively inhibits.

2.2 The Motor-Cognitive Connection: Handwriting vs. Typing

In early childhood and elementary education, resistance often focuses on the displacement of handwriting by keyboarding. This objection is rooted in neurodevelopmental science.

The “Reading Circuit” Activation

Functional MRI studies have demonstrated that handwriting recruits a specific “reading circuit” in the brain that typing does not. When a child writes a letter by hand, the motor pathway reinforces letter recognition and memory retention. Typing, which involves selecting a pre-formed key, does not create the same neural imprint.

Teachers who resist “1:1 Chromebook” initiatives in lower grades are often acting on this empirical reality. They argue that the efficiency of typing comes at the cost of cognitive engagement. Research supports the view that handwriting leads to better idea generation and deeper processing of content, whereas typing allows for faster transcription but shallower cognitive processing. Thus, resistance is a pedagogical choice to prioritize cognitive development over administrative efficiency.

2.3 Philosophical Resistance: Montessori and Waldorf Perspectives

Resistance is most articulate within specific pedagogical frameworks like Montessori and Waldorf, where technology is often viewed as fundamentally incompatible with the developmental needs of the child.

Montessori: The Concrete before the Abstract

Montessori pedagogy emphasizes sensory-rich, hands-on learning. The method relies on physical manipulation of “concrete” materials—beads, blocks, sandpaper letters—to build understanding before moving to abstraction. Technology, being inherently abstract and two-dimensional, conflicts with this foundational principle.

Montessori educators view screens as a barrier to the “normalization” of the child—a state of focused, calm engagement achieved through work with physical materials. While some Montessori schools introduce tech in upper elementary, resistance at the early levels is a defense of the “sensitive periods” where sensory input is critical. Teachers fear that “outsourcing” education to software diminishes the child’s agency and disrupts the prepared environment.

Waldorf: Protecting the Human Connection

Waldorf (Steiner) education takes a more rigid stance, often delaying screen exposure until high school. This resistance is rooted in the belief that early technology use induces “alienation” from the physical world and the labor of learning. Waldorf educators prioritize “unmediated” experiences—storytelling, art, and nature.

Critics call this the “Waldorf trap,” accusing it of elitism or Luddism. However, proponents argue that by protecting children from the “flattened sensory input” of the digital world, they are cultivating stronger capacities for empathy, imagination, and social resilience. For these teachers, resistance is a moral obligation to protect the “humanity” of the classroom.

2.4 The Erosion of Empathy and Social Interaction

Across all philosophies, a common thread of resistance is the fear that screens displace face-to-face interactions. The “Interaction Hypothesis” in language learning emphasizes that proficiency is forged in social contact.

Teachers observe that screens allow students to “edit” their interactions, avoiding the vulnerability of real-time communication. This “curated” interaction prevents students from learning how to navigate the messy dynamics of human relationships. Teachers resist technology when they see it turning a community of learners into isolated individuals. They argue that empathy is learned through the observation of micro-expressions and tone—data points often lost in digital communication.

Table 2: Cognitive and Pedagogical Conflicts

| Domain | Digital Mode | Analog/Traditional Mode | Teacher Resistance Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reading | Skimming, Scanning, F-Pattern processing. | Deep Reading, Linear processing, sustained attention. | “My students are losing the ability to follow complex arguments or feel empathy for characters because they scan for keywords.” |

| Writing | Typing: Fast, passive key selection, shallow processing. | Handwriting: Slow, active motor engagement, activates reading circuit. | “Writing by hand helps them remember. Typing is just transcription without thinking.” |

| Social | Curated, edited, asynchronous, flattened affect. | Vulnerable, real-time, rich sensory cues, micro-expressions. | “They text each other while sitting next to each other. They are losing the ability to read human emotion.” |

| Philosophy | Abstract, 2D, standardized, passive consumption. | Concrete, 3D, tactile, active manipulation. | “Children need to touch the world to understand it. A screen is a barrier to reality.” |

Part III: The Psychology of the Teacher – Fear, Identity, and Burnout

Beyond philosophical objections, resistance is often an emotional response to the vulnerability required by new technologies. Asking a teacher to adopt a new tool is asking them to return to the status of a novice, a transition that can be deeply threatening to their professional identity.

3.1 The Spectrum of Fear: Incompetence and Obsolescence

Fear in technology adoption manifests in distinct forms, from the fear of embarrassment to the existential fear of replacement.

The Fear of Incompetence

Teaching is a performance profession. Teachers perform daily before an exacting audience. The introduction of technology introduces a high risk of public failure. When technology fails—or the teacher fails to operate it—the flow of the lesson is broken, and the teacher’s authority is undermined.

For veteran teachers who have mastered their craft, the “learning effort curve” of new technology is steep and demoralizing. They may feel “e-incompetence,” a sense that their pedagogical expertise is devalued in favor of technical dexterity. This is exacerbated when students, often “digital natives,” possess greater technical fluency, reversing the power dynamic. Resistance is a defense against the humiliation of “not knowing”.

The Fear of Replacement (AI and Automation)

The rise of AI has reignited the fear of obsolescence. While educators are reassured that “technology will never replace great teachers”, generative AI’s ability to create lesson plans and tutor students creates anxiety. Teachers worry that the “caring” element of teaching is being devalued by systems prioritizing efficiency. The “robot teacher” narrative manifests in policies using software for “personalized learning,” sidelining the teacher to a facilitator role. Resistance to AI is resistance to the de-professionalization of teaching.

3.2 Technostress: Overload and Invasion

“Technostress” is a validated phenomenon defined as the inability to cope with new technologies in a healthy manner. It drives resistance through specific stressors.

Techno-Overload and Cognitive Load

Teachers report unprecedented cognitive load. Managing an LMS, emails, digital gradebooks, and online resources—while managing a classroom—creates “techno-overload”. The brain has limited working memory. When teachers navigate non-intuitive interfaces, cognitive resources are drained, leaving less energy for teaching. Resistance is a plea for cognitive preservation; teachers “hate technology” because they are exhausted by the “learning curve” that never flattens.

Techno-Invasion

Technology dissolves boundaries between work and home. The expectation of 24/7 connectivity leads to “techno-invasion”. This prevents psychological detachment, leading to burnout. Teachers resist new communication tools because they perceive them as “leashes” rather than supports.

3.3 The Veteran Teacher Paradox

Veteran teachers are often stereotyped as the primary source of resistance, but research indicates a more nuanced reality. They are often “pragmatic skeptics.” Having seen waves of “revolutionary” tools vanish (laserdiscs, clickers), they are wary of fleeting trends.

Pragmatism over Novelty

Veterans evaluate technology via efficiency and outcomes. If a tool does not demonstrably improve learning, they reject it. Unlike novices, who may use tech to survive management challenges, veterans have established styles that technology can disrupt. Their resistance is a demand for proof of value. When technology fails to align with their pedagogical content knowledge, they view it as a distraction.

Part IV: Institutional Failures – The Ecology of Pressure

Resistance is frequently a symptom of systemic failure.

Teachers function within institutions that impose technology in ways that ignore classroom realities, creating “coercive pressure” that guarantees pushback.

4.1 Top-Down Mandates and the Loss of Autonomy

The most cited cause of resistance is the “top-down” implementation model. Decisions are often made by administrators removed from the classroom.

The Disconnect of Decision Making

When reforms are “imposed from above,” teachers feel a loss of agency. They become “implementers” of another’s vision rather than partners. This leads to “initiative fatigue,” where teachers view new technology as “just another thing”. UNESCO reports “sins of omission” where jurisdictions fail to consult teachers or provide frameworks for integration. Hardware is purchased without training budgets, leaving teachers to bridge the gap.

Coercive Isomorphism

Institutional theory suggests schools adopt technology due to “coercive pressure”—the need to look modern—rather than educational need. When teachers sense technology is used for “optics” (e.g., “we are an iPad school”) rather than learning, cynicism fuels resistance.

4.2 Infrastructure and Reliability Friction

Nothing destroys confidence like unreliable infrastructure. “Techno-friction”—slow internet, broken devices—creates management crises. A teacher cannot lose 10 minutes of a period to troubleshooting.

When schools fail to provide “facilitating conditions” (UTAUT), resistance is a rational response to an unreliable environment. Teachers resist because they cannot trust the tech, and the reputational cost of failure falls on them.

Table 3: Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Implementation Impacts

| Feature | Top-Down Implementation | Bottom-Up / Participatory Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Decision Maker | Administrators, IT Directors, District Officials. | Teachers, Department Heads, Student feedback. |

| Teacher Perception | Loss of autonomy, “Cog in the machine,” De-professionalization. | Empowerment, Ownership, Professional Investment. |

| Morale Impact | Decreased job satisfaction, Burnout, Initiative Fatigue. | Increased morale, Higher efficacy, Sustainable change. |

| Adoption Style | Compliance (Doing it because I have to). | Commitment (Doing it because I want to). |

| Efficiency | High speed of decision, Low speed of adoption (Resistance). | Slower decision making, Faster/Deeper adoption. |

Part V: Strategic Frameworks for Support – From Coercion to Empathetic Leadership

Supporting teachers requires shifting from “managing resistance” to “supporting adaptation.” This involves empathetic leadership, structural changes to PD, and reducing friction.

5.1 The “Warm Demander” Leader

The “Warm Demander” concept, originally a pedagogical stance for culturally responsive teaching (coined by Kleinfeld), is highly effective for leadership. It combines high expectations (demand) with personal care (warmth).

Operationalizing Warmth and Demand

- The Warmth: The leader acknowledges the difficulty of change, validates fears, and builds psychological safety. They state, “I know this is hard, and I am here to support you”.

- The Demand: The leader maintains a clear vision for why technology is necessary for equity. They do not lower expectations but scaffold the path to meeting them.

This counters “laissez-faire” leadership (allowing resistance) and “authoritarian” leadership (breeding resentment). It frames adoption as professional growth within a supportive community.

5.2 Building Psychological Safety: The “Sandbox” Approach

To overcome fear of incompetence, schools must create “psychological safety”—an environment where risk is rewarded and failure is not punished.

The Digital Sandbox

A “sandbox” is an isolated testing environment where errors have no consequences. In PD, this means creating spaces for teachers to “play” with tech without students or evaluation.

Strategies for Sandbox PD:

- Play Time: Dedicate staff meetings to “messing around” with tools, no deliverables.

- The “Undo” Button: Teach recovery from errors (the “ripcord”) to reduce anxiety.

- Gamification: Use tech for fun, non-academic problems to build familiarity.

5.3 Instructional Coaching as Partnership

Traditional “training” (one-off workshops) is ineffective. Jim Knight’s Partnership Principles offer a superior model: coaching as a conversation between equals.

The Seven Principles in Action

- Equality: The coach is not the “expert” fixing the teacher; they are partners.

- Choice: Teachers choose which technologies to adopt and how.

- Voice: The teacher’s goals drive the cycle, not the coach’s agenda.

Scripting the Conversation:

Instead of “You should use this,” a partnership coach asks: “What barrier are your students facing?”. If the teacher says, “They don’t read,” the coach suggests: “I’ve seen a text-to-speech tool help. Want to try it?”. This shifts dynamic from compliance to problem-solving.

5.4 Bottom-Up Professional Development: Edcamps

To counter top-down fatigue, schools should leverage “bottom-up” models like Edcamps.

The Unconference Model

Edcamps are participant-driven; the agenda is created by attendees on the day of the event. There are no vendors or keynotes. Teachers choose sessions based on needs (e.g., “Help with Google Classroom”).

Why it Works:

- Agency: Teachers control learning.

- Relevance: Topics address real-world problems.

- Networking: Builds a “community of practice”.

5.5 Reducing Friction: The Principal as Buffer

Principals must “buffer” teachers from external incoherence. Effective leaders filter mandates, shielding teachers from “noise”.

The Friction Audit

Leaders should conduct “Technology Friction Audits” to remove barriers.

- Hardware: Are devices charged?

- Login: Single Sign-On (SSO) is crucial.

- Policy: Are filters blocking educational content?.

Proactively removing “pebbles in the shoe” demonstrates respect for teachers’ time.

5.6 Addressing the AI Elephant: From Policing to Literacy

Resistance to AI requires a nuanced approach. Shift the conversation from “How do we stop cheating?” to “How do we prepare students?”.

Strategies:

- Redefine Cheating: Co-create integrity policies with students.

- Focus on “Human” Skills: Emphasize that AI makes critical thinking and empathy more valuable.

- AI as Assistant: Show how AI reduces teacher workload (generating rubrics), turning the “enemy” into an “assistant”.

Detailed Analysis and Strategic Recommendations

6.1 The Friction Audit Checklist

To move from theory to practice, leaders can use a “Friction Audit” to diagnose resistance causes. This checklist derives from UTAUT’s “facilitating conditions”.

| Audit Category | Key Questions | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure | Is WiFi reliable everywhere? Are spare devices ready? | Eliminate “Techno-Uncertainty” |

| Logistics | How long is login? Do we use SSO? | Reduce “Techno-Overload” |

| Support | Is support punitive or restorative? | Build Psychological Safety |

| Policy | Are filters blocking educational content? | Empower “Digital Agency” |

| PD | Is training differentiated? Is there coaching? | Bridge TPACK Gap |

Insight: Resistance often correlates with “clicks” wasted. Reducing friction requires no belief change, only efficiency.

6.2 Scripts for Empathetic Leadership

Using “Warm Demander” and “Partnership” frameworks, leaders can use these scripts.

Scenario A: The Veteran Skeptic

Teacher: “I’ve taught this way for 20 years. This app is a distraction.”

Response: “You have incredible experience (Validation). I’m not asking you to replace what works. Is there a ‘pain point’ in your workflow this tool might solve? If not, let’s look together and decide (Choice/Voice).”

Scenario B: The Overwhelmed Novice

Teacher: “I can’t learn this LMS; I’m barely keeping up.”

Response: “I see your load (Empathy). Let’s take the LMS off your plate this week. Can we find 15 minutes to show you one feature to save time? If not, we won’t use it yet (Buffering).”

Scenario C: The Fearful Avoider

Teacher: “I don’t like using computers; kids get wild.”

Response: “It is scary to lose control (Validation). What if we tried a ‘Sandbox’ lesson where I co-teach? I’ll handle tech, you handle content (Shared Risk).”

6.3 Designing the “Sandbox” PD

Traditional PD demands “performance” too soon. The Sandbox inserts “exploration.”

Phase 1: The Playground (No Stakes)

Teachers use devices to “break it.”

- Activity: “Make the ugliest slide deck.”

- Outcome: Reduces fear of error.

Phase 2: The Lab (Low Stakes)

Peer pairs design one activity.

- Activity: “Create a 5-minute entrance ticket.”

- Outcome: Builds Self-Efficacy.

Phase 3: The Pilot (Supported Stakes)

Teachers run the activity with a safety net (coach present).

- Outcome: Transfers skill with safety.

Conclusion: Reframing Resistance as Engagement

The “resistant teacher” narrative is a convenient fiction absolving institutions of designing human-centered systems. When teachers resist, they signal a breakdown: a tool too hard to use, a mandate making no pedagogical sense, or an unmanageable workload.

By listening to the “signal” in resistance, leaders uncover deep-seated values. Teachers resist because they care—about deep reading, connection, attention spans, and integrity.

Supporting them requires moving from a “deficit model” (fixing teachers) to an “empowerment model” (removing barriers). Through Empathetic Leadership, Partnership Coaching, and Psychological Safety, schools transform resistance into engagement. The goal is not blind acceptance, but digital agency—choosing the right tools to serve the learner.

Key Takeaways

- Validate the “Why”: Acknowledge resistance often defends quality pedagogy. Address how tech coexists with deep learning.

- Audit Friction: Fix the environment before blaming mindset.

If WiFi is slow, resistance is rational.

- Be a “Warm Demander”: High-support, high-expectation. Build relationships before demanding change.

- Create Sandboxes: Allow “play” and “failure” in private.

- Focus on Agency: Use bottom-up PD (Edcamps) and coaching for voice/choice.

- Buffer Noise: Protect teachers from “initiative fatigue” by filtering mandates.

Final Thought:

Technology accelerates, but the teacher drives. If the driver is fearful, horsepower doesn’t matter. The leader’s job is to clear the road and support the driver.