Multimedia Integration in Education: Enhance Learning & Retention

Multimedia Integration: Bringing Lessons to Life in Education

Executive Introduction: The Cognitive and Pedagogical Imperative

The contemporary educational landscape is witnessing a profound metamorphosis, characterized fundamentally by a departure from the industrial-age model of knowledge transmission toward a post-industrial paradigm of knowledge construction. In the traditional “transmission” model, the instructor is conceptualized as the primary repository of information, and the learner as a passive vessel to be filled—a dynamic often disparagingly referred to as the “banking model” of education. However, the exigencies of the 21st century, coupled with substantial advances in cognitive science, have necessitated a shift toward student-centered learning environments where knowledge is actively constructed rather than passively received. Within this shifting paradigm, multimedia integration has emerged not merely as a technological accessory, but as a critical pedagogical catalyst that leverages the fundamental architecture of human cognition to enhance understanding, retention, and transfer of learning.

Multimedia integration—defined broadly as the synchronized presentation of verbal (text or narration) and pictorial (images, animation, video) material—is no longer an optional enhancement for the well-resourced classroom; it is a central component of modern instructional design. The efficacy of this approach is grounded in the empirical recognition that the human brain does not process information in a singular stream. Rather, it utilizes distinct channels for visual and auditory processing, a biological reality that educational systems must exploit to maximize learning potential. By engaging both channels simultaneously, educators can bypass the bottlenecks of working memory and facilitate the encoding of deeper, more robust mental models in long-term memory.

This report offers an exhaustive analysis of multimedia integration in education. It traverses the theoretical foundations established by cognitive psychologists such as Richard Mayer and Allan Paivio, examines the practical applications ranging from high-fidelity Virtual Reality (VR) to low-tech paper-based strategies, and addresses the systemic challenges of implementation, assessment, and equity. By synthesizing data from diverse educational contexts—from primary schools in Scotland to higher education lecture halls—this document serves as a comprehensive blueprint for stakeholders seeking to operationalize multimedia learning to its fullest potential.

Part I: The Cognitive Architecture of Learning

To understand why multimedia integration is effective—and how it can fail—one must first possess a nuanced understanding of the cognitive architecture of the learner. Instructional design is effectively engineering for the human mind; thus, the constraints and capabilities of the brain determine the parameters of effective teaching. The integration of multimedia is grounded in three seminal theories: the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML), Dual Coding Theory, and Cognitive Load Theory (CLT).

1.1 The Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML)

Developed extensively by Richard E. Mayer, the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning provides the primary theoretical framework for this report. It posits a constructivist view of learning, asserting that deep learning occurs only when the learner actively engages in a coordinated set of cognitive processes: selecting relevant information, organizing it into coherent mental representations, and integrating it with prior knowledge. Mayer’s theory is predicated on three non-negotiable assumptions about human cognition, which serve as the “physics” of the instructional design world.

The Dual-Channel Assumption

The first pillar of CTML is the Dual-Channel Assumption, which suggests that humans possess separate information processing channels for visually represented material and auditorily represented material. This concept is derived from Paivio’s earlier work and suggests that when information is presented solely through text, it engages only the visual channel (unless the learner mentally vocalizes the text, engaging the auditory loop). Conversely, a lecture engages the auditory channel. True multimedia learning occurs when instruction taps into both channels simultaneously—for example, by presenting an animation (visual) accompanied by concurrent narration (auditory). This dual-modality approach allows the learner to process more total information than would be possible through a single channel, effectively expanding the bandwidth of the working memory system.

The Limited-Capacity Assumption

The second pillar is the Limited-Capacity Assumption, which acknowledges the severe constraints of human working memory. Research indicates that individuals can only hold and process a very small amount of information in each channel at any one time—often cited as “seven plus or minus two” chunks, though modern research suggests even fewer for complex processing. This assumption is critical for multimedia design because it implies that “more” is not always “better.” If an instructional designer bombards the learner with on-screen text, complex diagrams, background music, and rapid-fire narration simultaneously, the limited capacity of the visual and auditory channels is quickly exceeded. The result is cognitive overload, where the learner fails to process the essential material because their mental resources are consumed by managing the influx of data.

The Active-Processing Assumption

The third pillar, the Active-Processing Assumption, challenges the passive view of learning. It asserts that humans are not video recorders that simply store information presented to them. Instead, meaningful learning requires significant cognitive effort. The learner must actively pay attention to incoming information (selection), construct connections between the new pieces of information (organization), and relate this new structure to existing knowledge stored in long-term memory (integration). Multimedia tools are therefore not delivery trucks for information; they are cognitive aids that scaffold these active processes. The instructor’s role shifts from broadcasting content to designing environments that encourage and guide this active cognitive work.

1.2 Principles of Multimedia Design

Based on these assumptions, Mayer and his colleagues have identified a suite of evidence-based principles that guide effective multimedia design. These principles are not merely stylistic suggestions; they are mechanisms for managing cognitive load and ensuring that the learner’s limited mental resources are directed toward germane processing.

- Multimedia Principle (Dual Coding Theory): People learn more deeply from words and pictures than from words alone. Application: Textbooks should never be walls of text; they must include relevant diagrams, charts, or photographs that explicate the text.

- Spatial Contiguity Principle (Split-Attention Effect): People learn better when corresponding words and pictures are presented near each other rather than far apart. Application: In a diagram of the human eye, labels should be placed directly on the retina, cornea, and lens, rather than using a numbered legend at the bottom of the page, which forces the eye to scan back and forth.

- Temporal Contiguity Principle (Associative Processing): Learning is enhanced when corresponding words and pictures are presented simultaneously rather than successively. Application: When showing an animation of a pump, the narration describing the “intake valve opening” must occur at the exact second the valve opens on screen, not before or after.

- Coherence Principle (Extraneous Load Reduction): People learn better when extraneous words, pictures, and sounds are excluded rather than included. Application: Educators must ruthlessly edit their materials. Background music in an instructional video or decorative clip art on a slide distracts from the learning goal and should be eliminated.

- Modality Principle (Channel Offloading): People learn better from graphics and narration than from graphics and on-screen text. Application: When presenting a complex visual simulation, use voiceover to explain it rather than subtitles. Reading subtitles competes for visual attention with the animation, whereas listening uses the separate auditory channel.

- Signaling Principle (Selective Attention): Learning is deepened when cues are added that highlight the organization of the essential material. Application: Use arrows, highlighting, bold text, or vocal emphasis to guide the learner’s attention to the specific part of the screen being discussed.

- Redundancy Principle (Redundancy Effect): People learn better from graphics and narration than from graphics, narration, and on-screen text. Application: Do not read your PowerPoint slides to your students. Presenting the exact same words in text and speech forces the brain to process the same data twice, causing interference.

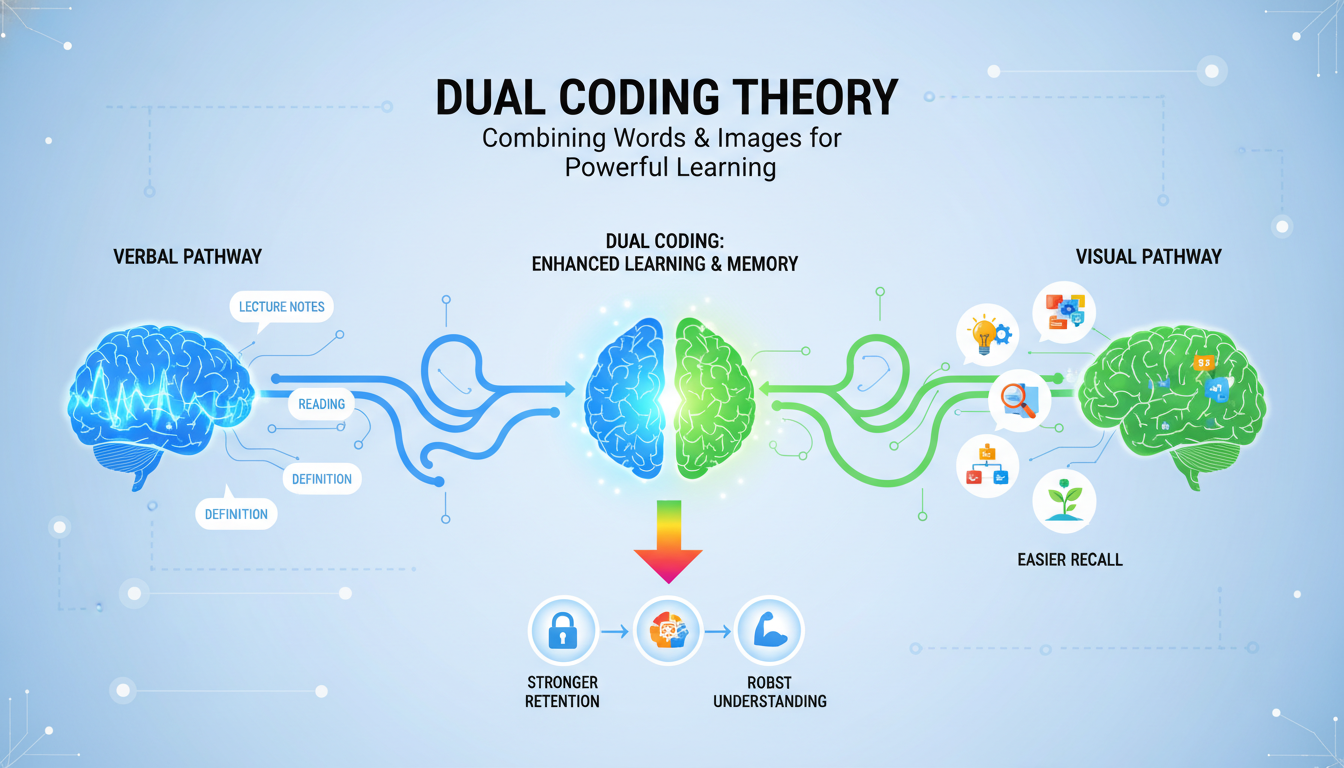

1.3 Dual Coding Theory: The Foundation of Representation

Parallel to Mayer’s work is Allan Paivio’s Dual Coding Theory (DCT), which provides the granular psychological explanation for why the combination of text and image is so potent. Developed in 1971, DCT posits that the human cognitive system consists of two distinct subsystems: a verbal system for processing language (logogens) and a non-verbal system for processing imagery (imagens).

The central thesis of DCT is that these two systems are functionally independent but interconnected. This means that a learner can process a word without visualizing it, or visualize an object without naming it, but the strongest memory traces are formed when both systems are activated.

When a concept is “dual coded”—that is, represented both verbally and visually—it creates two separate pathways for retrieval in the brain. If the verbal memory trace fades, the visual one may remain, and vice versa, effectively doubling the probability of later recall.

In the context of education, DCT refutes the notion that imagery is merely “illustrative” or secondary to text. Instead, it argues that imagery is a primary mode of cognition. For educators, this means that providing a visual representation—such as a diagram, a timeline, or a concept map—is not “dumbing down” the curriculum; it is providing a second, robust cognitive hook for the information. It is crucial, however, to distinguish DCT from the controversial and largely debunked “Learning Styles” theory. DCT does not suggest that some students are “visual learners” and others are “verbal learners.” Rather, it asserts that all human brains function more efficiently when both modalities are engaged. The integration of visuals benefits the “verbal” student just as much as the “visual” student by providing a complementary mental model.

1.4 Cognitive Load Theory (CLT): Managing Mental Effort

The practical application of CTML and DCT is governed by Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), which focuses on the limitations of working memory. Sweller and colleagues categorize the cognitive load experienced during learning into three distinct types, a distinction that is vital for multimedia design:

- Intrinsic Cognitive Load: This is the inherent difficulty associated with the specific instructional topic. For instance, learning the periodic table has a high intrinsic load due to the number of elements and their complex relationships, whereas learning the names of primary colors has a low intrinsic load. Educators cannot simply “remove” intrinsic load without simplifying the content to the point of inaccuracy, but they can manage it by segmenting complex material into smaller, digestible chunks.

- Extraneous Cognitive Load: This load is generated by the manner in which information is presented to learners. If a diagram is located on page 4 and the explanatory text is on page 5, the learner must expend significant mental energy flipping back and forth and holding the image in working memory while reading. This effort does not contribute to learning; it is waste. The primary goal of multimedia design principles (like Spatial Contiguity) is to minimize extraneous load so that working memory capacity is available for actual learning.

- Germane (Generative) Cognitive Load: This refers to the mental effort dedicated to processing, construction, and automation of schemas. This is the “good” load—the effort of understanding. Effective multimedia instruction seeks to reduce extraneous load specifically to free up capacity for germane load. When students are not struggling to navigate a poorly designed interface or decode confusing layouts, they can dedicate their mental energy to building complex mental models.

The “Split-Attention Effect” is a classic manifestation of high extraneous load. When learners are forced to split their attention between disparate sources of information that are unintelligible in isolation (e.g., a chart with no labels and a separate text description), learning suffers. Integrated formats, where text and graphics are physically integrated, consistently result in superior learning outcomes because they eliminate the need for unnecessary mental integration.

Part II: Pedagogical Frameworks for Multimedia Implementation

The integration of multimedia into the educational ecosystem requires more than just an understanding of cognitive mechanics; it demands a restructuring of pedagogical approaches. The transition from a teacher-centric model to a learner-centric model is facilitated by specific frameworks that leverage multimedia to change the dynamics of the classroom.

2.1 The Flipped Classroom Model

The Flipped Classroom represents one of the most significant structural shifts enabled by multimedia technologies. In this model, the traditional sequence of instruction is inverted: direct instruction, typically delivered via lecture, moves to the individual learning space (homework) through the use of video or interactive media, while the group learning space (classroom) is transformed into a dynamic environment for interactive application, discussion, and problem-solving.

Theoretical Alignment and Benefits

The efficacy of the Flipped Classroom is deeply rooted in the principles of active learning and self-regulation. By offloading the lower levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy (Remembering and Understanding) to pre-class video work, educators can dedicate valuable face-to-face time to the higher levels (Applying, Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating).

- Pacing and Autonomy: One of the most critical benefits is the democratization of pacing. In a live lecture, the instructor proceeds at a single speed. In a flipped model, students utilizing multimedia videos can pause, rewind, and re-watch complex segments as many times as necessary. This self-pacing is particularly beneficial for students who require additional processing time or for English Language Learners (ELLs) who may need to review vocabulary.

- Teacher as Guide: The role of the instructor shifts from “sage on the stage” to “guide on the side.” During class time, the teacher circulates, providing just-in-time feedback and individualized support as students grapple with difficult problems. This high-contact interaction is made possible because the lecture delivery has been automated via multimedia.

- Multimedia Integration Strategies: Effective flipping relies on more than just recording a 45-minute lecture. Best practices suggest “chunking” content into short (5-10 minute) videos to respect cognitive load limits. Furthermore, accountability mechanisms such as embedded quizzes (using tools like Edpuzzle) ensure that students engage with the material rather than passively letting it play in the background.

Challenges and Considerations

While powerful, the Flipped Classroom is not without challenges. It relies heavily on student self-discipline and access to technology outside of school—a significant equity concern. “Digital divide” issues mean that students without reliable internet at home may be disadvantaged. Schools must address this by providing offline access options or dedicated time/space within the school day for accessing multimedia content. Additionally, the “front-loading” of work can encounter resistance from students accustomed to passive listening; clear communication regarding the benefits of active learning is essential for buy-in.

2.2 Gamification and Game-Based Learning

Gamification refers to the application of game-design elements and game principles in non-game contexts, while Game-Based Learning (GBL) involves using actual games to achieve learning outcomes. Both approaches leverage multimedia to tap into the psychological drivers of motivation, engagement, and reward.

The Psychology of Engagement

Gamification works by satisfying fundamental human psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

- Immediate Feedback Loops: In traditional education, a student might wait days for a grade on a quiz. In a gamified multimedia environment, feedback is instantaneous. If a student answers incorrectly, the system provides immediate correction, allowing the learner to adjust their mental model in real-time. This prevents the fossilization of misconceptions and reinforces the connection between effort and outcome.

- Progress Visualization: Elements such as progress bars, badges, and leveling up provide visual indicators of competence and growth. The brain’s reward system, particularly the release of dopamine, is triggered by these incremental achievements, fostering a state of “flow” and sustaining motivation through difficult tasks.

- Narrative and Immersion: Effective gamification often wraps content in a narrative layer—a “quest” or “mission.” This narrative context transforms abstract academic tasks into meaningful goals (e.g., “solving these equations to navigate the spaceship”).

Operationalizing Gamification

For 2025 and beyond, best practices emphasize “intrinsic” gamification over “extrinsic” pointsification. This means the game mechanics should be deeply integrated with the learning content, rather than just a superficial layer of points for completing worksheets (often derided as “chocolate-covered broccoli”).

- Leaderboards and Competition: While leaderboards can motivate high achievers, they can demotivate struggling students. Modern systems often use “relative” leaderboards (comparing a student to their own past performance) or team-based competitions to foster collaboration rather than isolation.

- Tools: Platforms like Kahoot! and Quizizz turn formative assessment into a high-energy, interactive game show experience, while tools like Classcraft allow teachers to manage classroom behavior through a persistent role-playing game (RPG) layer.

2.3 Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework intended to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn. Multimedia is the engine that makes UDL possible in the modern classroom.

The Three Principles of UDL

- Multiple Means of Representation (The “What” of Learning): Learners differ in the ways that they perceive and comprehend information that is presented to them. Multimedia allows educators to present the same concept through text, audio, video, and interactive simulation simultaneously. This ensures that a student with a visual impairment, a student with dyslexia, or a student who simply processes auditory information better can all access the curriculum without stigmatizing “accommodations”.

Multiple Means of Action and Expression (The “How” of Learning)

Learners differ in the ways that they can navigate a learning environment and express what they know. Multimedia tools allow students to demonstrate mastery not just through a written essay, but through a podcast, a video presentation, a digital graphic, or a coded animation. This flexibility allows students to bypass specific barriers (e.g., dysgraphia) to show their true cognitive understanding.

Multiple Means of Engagement (The “Why” of Learning)

Learners differ markedly in the ways in which they can be engaged or motivated to learn. Some are engaged by spontaneity and novelty (e.g., a gamified challenge), while others are disengaged, even frightened, by those aspects, preferring strict routine. Multimedia offers personalized pathways, allowing students to choose topics or modalities that align with their interests and affective needs.

Part III: The Spectrum of Technological Modalities

The implementation of multimedia learning occurs across a spectrum of technologies, ranging from cutting-edge immersive environments to accessible, low-tech solutions. Each modality offers unique affordances for learning.

Immersive Technologies: Virtual and Augmented Reality

Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) represent the frontier of multimedia, offering experiences that transcend the limitations of the physical classroom. These technologies provide “immersion”—the psychological sensation of being present in a non-physical world—which has profound implications for memory and empathy.

Virtual Reality (VR): The Power of Presence

VR completely replaces the user’s visual and auditory environment. In education, this allows for “impossible” field trips and safe simulation of dangerous tasks.

- Experiential Learning: VR allows students to explore the International Space Station, walk through the circulatory system, or visit ancient Rome. This experiential learning utilizes the brain’s spatial memory systems, encoding information as an “experience” rather than just a “fact”.

- Case Study: Mearns Primary School (Scotland): At Mearns Primary, educators moved beyond passive consumption of VR. Students first drew physical wraparound landscapes, then used 360-degree cameras to digitize their creations. They annotated these virtual worlds using ThingLink and explored them via headsets. This integration of traditional art with high-tech VR transformed students from consumers into creators, fostering deep engagement and digital literacy.

- Vocational Training: In technical fields, VR is indispensable for safety. Students can practice welding, chemical mixing, or surgical procedures in a virtual environment where mistakes have no physical consequences. This “safe failure” builds confidence and muscle memory before students engage with real-world hazards.

Augmented Reality (AR): Overlaying Information

AR overlays digital information onto the real world, typically viewed through a tablet or smartphone. It bridges the gap between the abstract and the concrete.

- Interactive Manipulatives: Tools like zSpace or Merge Cube allow students to hold a physical object (a cube) while seeing a digital hologram (e.g., a beating heart or a geologic fault line) on their screen. They can rotate and dissect the virtual object, providing a tactile interface for complex 3D visualizations that static textbooks cannot match.

- Accessibility: Unlike high-end VR which requires headsets, AR often runs on standard tablets or phones, making it a more accessible entry point for many schools. Apps like Google Expeditions (AR mode) allow students to bring virtual artifacts into their own classroom space.

Digital Storytelling

Digital storytelling is the practice of combining narrative with digital content, including images, sound, and video, to create a short movie or presentation. It is a powerful pedagogical tool that synthesizes literacy, creativity, and technical skills.

The Pedagogical Process

Effective digital storytelling is not just about the final product; the learning is in the process.

- Scripting and Storyboarding: Before touching a computer, students must write scripts and draw storyboards. This planning phase forces students to organize their thoughts and select the most salient information (active processing), reducing cognitive load during the technical production phase.

- Media Curation and Creation: Students learn to search for relevant images or create their own art. This engages the “Selection” phase of Mayer’s theory, as students must decide which visual best supports their verbal narrative (Coherence Principle).

- Synthesis and Editing: In the editing suite, students must align their voiceover with their images (Temporal Contiguity). They must decide when to cut and when to linger. This recursive process of review and refinement deepens their understanding of the subject matter.

Outcomes and Benefits

Research indicates that digital storytelling enhances a wide range of skills. It improves traditional literacy (writing, speaking) while developing “new literacies” such as visual literacy and media fluency. Furthermore, when students share personal or cultural stories, it fosters empathy and classroom community, validating diverse student identities.

Interactive Simulations in STEM

In the fields of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM), interactive simulations (e.g., PhET, Gizmos) have revolutionized instruction by allowing students to experiment with variables in dynamic systems.

- Visualizing the Invisible: Many STEM concepts (e.g., electron flow, gravitational fields, molecular bonding) are invisible to the naked eye. Simulations render these invisible forces visible, helping students construct accurate mental models of abstract phenomena.

- Inquiry-Based Exploration: Simulations allow for rapid hypothesis testing. A student using a “projectile motion” simulation can instantly change the angle of a cannon and see the result. They can run 50 “trials” in the time it would take to set up one physical experiment. This encourages a “what if?” mindset and allows for deep exploration of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Data Integration: Modern simulations often include real-time graphing tools. As the student manipulates the simulation, a graph is generated simultaneously. This dual representation (visual action + graphical data) helps students bridge the gap between physical events and their mathematical representations.

Low-Tech and No-Tech Multimedia Integration

A pervasive myth in education is that multimedia integration requires expensive hardware. However, the cognitive benefits of “multimedia”—combining words and pictures—can be achieved with low-tech or no-tech solutions, which is critical for under-resourced schools.

- Paper Slides and “Low-Fi” Video: Students can create “videos” by drawing images on paper and sliding them in front of a camera (or just a frame) while narrating. This “paper slide” technique forces the same cognitive processes as high-end video production—sequencing, dual coding, and summarizing—without the need for complex software.

- Living Sentences: In this no-tech activity, students hold cards with words or punctuation and physically move around the room to form sentences. This engages the visual system (seeing the words), the auditory system (discussing the order), and the kinesthetic system (moving bodies), effectively “multimedia” learning through physical space.

- Leveraging Existing Infrastructure: In low-resource settings, existing technologies like radio, TV, and basic mobile phones can be repurposed. For instance, studies in the Philippines have shown that simple mobile phone-based tutoring can boost numeracy scores by 65%. The key is not the sophistication of the tech, but the pedagogical design—using the available channel to deliver targeted, active learning tasks.

- Dual Coding on the Blackboard: A teacher who draws a diagram on the blackboard while explaining a concept is using multimedia. The effectiveness depends on the adherence to principles like Contiguity (drawing and talking at the same time) rather than the cost of the screen.

Part IV: Implementation Strategy and Practical Design

Transitioning to a multimedia-rich environment requires a deliberate design strategy. It is not enough to simply “add tech.” Educators must adopt a designer’s mindset, focusing on the alignment between the tool, the content, and the learner.

Designing the Multimedia Lesson: A Step-by-Step Approach

To avoid the common pitfall of “technocentrism” (focusing on the tool rather than the learning), educators should follow a structured instructional design process:

- Define Learning Objectives: Clear goals are the foundation. Is the objective to memorize a fact, understand a process, or develop a skill? Multimedia is best suited for processes and skills; static text may suffice for simple facts.

- Select the Modality: Choose the simplest medium that achieves the goal. Do not use VR if a simple diagram works. Unnecessary complexity increases extraneous cognitive load.

- Storyboard and Script: Plan the lesson on paper. This is where the principles of CTML are applied. Check for Redundancy (is the text just a transcript of the audio?) and Coherence (are there distracting elements?).

- Produce and Curate: Create the assets or curate them from high-quality repositories (e.g., Khan Academy, National Geographic). Ensure quality—poor audio or blurry images increase cognitive strain.

- Integrate Active Learning: A video should never be a standalone activity.

It must be sandwiched between active tasks: a pre-viewing prediction question, an embedded quiz during the video, and a post-viewing application task.

4.2 Assessment: Grading Multimedia Projects

When students create multimedia, grading can be subjective. It is essential to use rubrics that separate “production value” (flashiness) from “content mastery” (substance).

Developing Effective Rubrics:

A robust multimedia rubric should include distinct criteria:

- Content Knowledge (40-50%): This is the most important section. Does the project demonstrate accurate, deep understanding of the subject matter? Are sources cited correctly?

- Organization and Clarity (20-30%): Is the narrative logical? Does the sequence of information make sense? This assesses the student’s organizational processing.

- Multimedia Design (10-20%): Did the student apply multimedia principles? Do the images support the text? Is the audio clear? This measures their communication skills, not just their technical skills.

- Creativity and Originality (10%): Is the approach novel? Did the student take risks?

- Technical Functionality (Pass/Fail or low weight): Does the link work? Is the file format correct? Technical glitches should be learning moments, not primary causes for failure.

Standardization: Using consistent rubrics across a school helps students understand that multimedia production is a serious academic endeavor, distinct from casual social media use.

Part V: Special Contexts, Equity, and Challenges

The implementation of multimedia is not without systemic challenges. Issues of equity, accessibility, and teacher readiness must be addressed to ensure that the benefits of multimedia are shared by all.

5.1 Multimedia in Special Education

Research indicates that multimedia learning can be particularly transformative for students with special educational needs (SEN).

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): For students with ASD, the social nuances of face-to-face instruction can be overwhelming. Multimedia Learning Objects (MLOs) provide a controlled, predictable environment where the student can control the pace and repetition of the input. Research suggests that well-designed multimedia systems can significantly improve learning outcomes for autistic students by reducing social anxiety and focusing attention on the essential content.

- Down Syndrome and Auditory Processing: Students with Down Syndrome often have stronger visual processing skills relative to their auditory processing. Multimedia that leans heavily on visual supports (icons, animations) can scaffold their learning, compensating for verbal working memory deficits. The ability to repeat audio segments indefinitely also supports those with auditory processing delays.

- Differentiation: Multimedia allows for “stealth differentiation.” In a single classroom, students can be working on the same topic but using different multimedia assets—some watching a basic introductory video, others engaging with a complex simulation—without the stigma of being pulled out of the class.

5.2 Addressing the Digital Divide

The “Digital Divide” is a major barrier to equitable multimedia integration. It manifests in two forms: the access gap (who has the devices) and the usage gap (how the devices are used).

- Infrastructure Challenges: High-bandwidth multimedia (VR, streaming video) requires robust internet connectivity. In rural or under-funded urban schools, this infrastructure may be lacking. Solutions include offline-first technologies, local caching servers, or low-bandwidth alternatives (e.g., downloading content during off-hours).

- The Usage Gap: Research shows that students in affluent schools often use technology for creative, high-agency tasks (coding, video production), while students in low-income schools often use it for passive drill-and-practice. Educators must consciously fight this trend by ensuring that all students, regardless of socioeconomic status, are given opportunities to be creators and critical thinkers with technology.

- Scalable Solutions: To address inequity, schools should prioritize “device-agnostic” tools—web-based platforms that run on any device (Chromebooks, old tablets, phones)—rather than expensive, proprietary hardware ecosystems that are difficult to sustain.

5.3 Teacher Training and TPACK

Perhaps the single greatest determinant of success is not the hardware, but the teacher. A lack of adequate training leads to “bad buys”—expensive tech gathering dust in closets.

The TPACK Framework:

Effective technology integration requires the intersection of three knowledge domains:

- Content Knowledge (CK): Knowing the subject matter.

- Pedagogical Knowledge (PK): Knowing how to teach.

- Technological Knowledge (TK): Knowing how to use the tools.

True integration happens at the center (TPACK), where a teacher knows how to use a specific tool to teach a specific concept effectively. Professional development must therefore move beyond “how to use this software” sessions to “how to teach science with this software” workshops. Teachers need time to explore, fail, and collaborate to build this integrated knowledge.

Conclusion: Synthesizing the Future of Learning

The integration of multimedia into education is not a transient trend; it is a fundamental realignment of instructional practice with the biological realities of the human mind. The evidence, spanning decades of cognitive research, is incontrovertible: humans learn more deeply when words and pictures are combined than when words are used alone.

From the high-tech immersion of Virtual Reality labs in Scotland to the low-tech ingenuity of paper slides in resource-constrained classrooms, the principles remain the same. Success lies not in the sophistication of the device, but in the fidelity of the design to cognitive principles. When educators respect the dual-channel nature of the mind, manage the limited capacity of working memory, and design for active processing, they unlock potential that traditional transmission models simply cannot reach.

As we look to the future, the challenge is no longer access to information, but the curation and synthesis of it. Multimedia tools—when implemented with pedagogical rigor, equitable intent, and a focus on student agency—empower learners to navigate this complex landscape. They transform the classroom from a place of passive reception into a vibrant studio of active construction, where lessons are not just heard, but seen, experienced, and truly brought to life.

Key Recommendations for Stakeholders

| Stakeholder | Actionable Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Teachers | Audit your materials: Apply the Coherence Principle immediately. Remove distracting music, decorative images, and redundant text from your slides. Start small with one “flipped” lesson or one digital storytelling project. |

| Administrators | Invest in TPACK, not just Tech: For every dollar spent on hardware, spend a dollar on professional development. Ensure PD focuses on pedagogy, not just button-pushing. |

| Policymakers | Bridge the Divide: Prioritize infrastructure (broadband) as a basic utility for schools. Promote policies that support open educational resources (OER) to ensure high-quality multimedia is available to all. |

| Instructional Designers | Design for Accessibility: Use UDL principles from the start. Caption all video, describe all images, and ensure simulations are keyboard navigable. |

The future of education is multimedia, not because it is “modern,” but because it is human.