Technology Acceptance Models in Education: TAM & UTAUT Analysis

Epistemological Foundations and the Imperative of Adoption Research

The proliferation of digital technologies within the educational sector—spanning K-12 classrooms, higher education institutions, and asynchronous professional development platforms—represents one of the most significant structural shifts in the history of pedagogy. However, the mere availability of sophisticated tools, from Learning Management Systems (LMS) to Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Metaverse, does not guarantee their effective utilization. The gap between technological potential and actual pedagogical integration has birthed a massive domain of inquiry focused on “acceptance.” At the heart of this inquiry lie specific theoretical frameworks—primarily the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)—which serve as the lens through which researchers, administrators, and policymakers attempt to predict and influence human behavior in educational settings.

Understanding these models is not merely an academic exercise; it is a strategic imperative. As educational institutions invest billions in digital infrastructure, the failure to adopt—or the “passive resistance” often seen in faculty bodies—represents a catastrophic loss of resources and opportunity. These models frame the vast majority of adoption research, dictating what variables are measured (e.g., “ease of use”) and, consequently, what variables are ignored (e.g., “sociomaterial constraints” or “teacher burnout”). By analyzing the architecture, evolution, and limitations of these models, stakeholders can move beyond simplistic “training sessions” toward a nuanced understanding of the sociotechnical ecosystem of the school.

The dominance of these frameworks is staggering. A systematic review of educational technology literature reveals that the vast majority of studies utilize TAM or its extensions to validate the introduction of new tools. Whether the technology in question is a mobile learning app in rural China, an electronic medical record system in a teaching hospital, or a VR headset in a middle school, the theoretical scaffold remains remarkably consistent. This ubiquity, however, invites scrutiny. Does a model designed to predict spreadsheet usage in 1980s corporate America truly capture the complex, emotional, and mandatory reality of a modern classroom? This report dissects the theoretical lineage from TAM to UTAUT, analyzes the dialectic between usefulness and ease of use, and critiques the variance-based approach through the lens of sociomateriality and institutional theory.

The Theoretical Lineage: From Rational Action to Technology Acceptance

To understand the dominance of TAM in education, one must trace its roots to social psychology. TAM is an adaptation of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), which posited that behavioral intention is a function of attitude and subjective norms. Fred Davis, in his seminal 1989 work, distilled this into a parsimonious model specifically for information systems, proposing that two specific beliefs—Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)—were the primary determinants of attitude and, subsequently, intention.

In the educational context, this rationalist perspective assumes that teachers and students operate as “utility maximizers.” The theory suggests that if a teacher perceives a digital tool as enhancing their pedagogical output (PU) and requiring minimal cognitive load to master (PEOU), they will rationally choose to adopt it. This logic is seductive in its simplicity and has allowed for the rapid scaling of quantitative research. Researchers can deploy standardized surveys to hundreds of participants, generating regression models that explain 40-50% of the variance in intention.

However, the transition from corporate to educational contexts introduces friction. In a corporation, “job performance” is often quantifiable (e.g., reports filed, sales made). In education, “performance” is nebulous, involving student engagement, emotional support, standardized test scores, and long-term developmental outcomes. Consequently, the definitions of PU and PEOU have had to evolve, leading to the sophisticated—and sometimes contested—extensions of the model we see today.

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and TAM2: The Gold Standard and Its Evolution

Deconstructing the Core Constructs in Education

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) serves as the “fruit fly” of educational technology research—studied, dissected, and replicated more than any other framework. Its endurance is attributed to its statistical reliability and the adaptability of its two core constructs.

Perceived Usefulness (PU): The Engine of Adoption

Perceived Usefulness is defined as the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance their job performance. In education, this is the most potent predictor of adoption. Teachers are pragmatic professionals; they operate under severe time constraints and pressure to deliver learning outcomes. Consequently, the threshold for “usefulness” is high. A tool must not merely be “cool”; it must solve a specific pedagogical problem, such as automating assessment, differentiating instruction for diverse learners, or visualizing abstract concepts.

Research consistently shows that PU correlates more strongly with usage behavior than any other variable. For example, in studies of e-learning adoption during the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers who perceived digital platforms as vital for maintaining instructional continuity (high PU) adopted them despite severe usability issues (low PEOU). This suggests that utility can override complexity, a finding that has profound implications for software design in EdTech.

Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU): The Gatekeeper

Perceived Ease of Use refers to the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort. While PU drives long-term retention, PEOU acts as the initial gatekeeper. If a teacher opens a software program and cannot navigate the interface within minutes, the “cognitive tax” is deemed too high, and the tool is abandoned before its “usefulness” can be ascertained.

Statistical analyses reveal a causal relationship where PEOU functions as an antecedent to PU. A system that is easier to use is perceived as more useful simply because it consumes fewer resources (time and attention) to achieve the same outcome. In educational settings involving younger students or digital immigrants, PEOU takes on heightened importance. For K-12 teachers, “ease of use” often translates to “classroom management stability”—knowing that the technology will not fail or confuse students during a 45-minute lesson.

TAM2: Incorporating Social Norms and Cognitive Processes

While TAM explained that usefulness matters, it failed to explain why a user perceives a system as useful. To address this, Venkatesh and Davis proposed TAM2, which incorporated social influence processes and cognitive instrumental processes.

Subjective Norms in the Faculty Room

TAM2 introduces Subjective Norms—the perception that important others think one should use the system. In the hierarchical and collegial environment of a school, this is critical. A teacher’s decision to adopt a Learning Management System (LMS) is rarely made in a vacuum; it is influenced by the principal’s directives, the department head’s preferences, and the peer pressure of colleagues.

Studies applying TAM2 in educational healthcare settings (e.g., teaching hospitals) illustrate that Subjective Norms are particularly powerful in mandatory settings but their influence decays over time as users gain direct experience with the system. In K-12 education, the “Subjective Norm” often emanates from the students themselves or their parents. Research in Vietnam regarding social media usage by teachers indicated that pressure from parents and students significantly influenced teachers’ perceived usefulness of the tools, effectively forcing adoption through social expectation.

Job Relevance and Output Quality

TAM2 also separates the concept of utility into Job Relevance (does this apply to my subject?) and Output Quality (does it do the job well?). This granularity is vital for analyzing subject-specific friction. A math teacher might find a graphing calculator app highly “Job Relevant,” while an English teacher finds it irrelevant, regardless of its superior interface. This distinction helps explain why generic “EdTech” often fails; tools must be perceived as relevant to the specific domain knowledge of the educator.

Empirical Validation and the “Illusion of Progress”

The application of TAM in education has generated a massive volume of data confirming its basic tenets. A meta-analysis of 47 studies from 2003 to 2021 found that TAM and its extensions remain the most validated models in the field. However, critics argue that this continuous replication creates an “illusion of progress”. By repeatedly proving that “usefulness predicts intention,” researchers may be ignoring the more complex, messy realities of why implementation fails despite positive intentions.

Specifically, TAM is criticized for being overly deterministic and ignoring the “black box” of actual usage. It measures intent to use, but not how the technology is used. A teacher might “adopt” an interactive whiteboard (validating TAM) but use it merely as a projection screen for static PowerPoints.

This “shallow adoption” is a pervasive issue in education that standard TAM surveys fail to detect, as they lack the qualitative nuance to distinguish between transformative integration and mere digitization of traditional practices.

Construct

PU

- Pedagogical Utility

- “This app improves student reading scores.”

- Strongest predictor of Intention.

PEOU

- Interface/Cognitive Load

- “I can learn this software in 10 minutes.”

- Antecedent to PU; Gatekeeper.

Subjective Norm

- Administrative/Peer Pressure

- “The Principal expects us to use Canvas.”

- Strong in mandatory settings.

Job Relevance

- Curricular Alignment

- “This simulation fits my chemistry syllabus.”

- Determinant of PU.

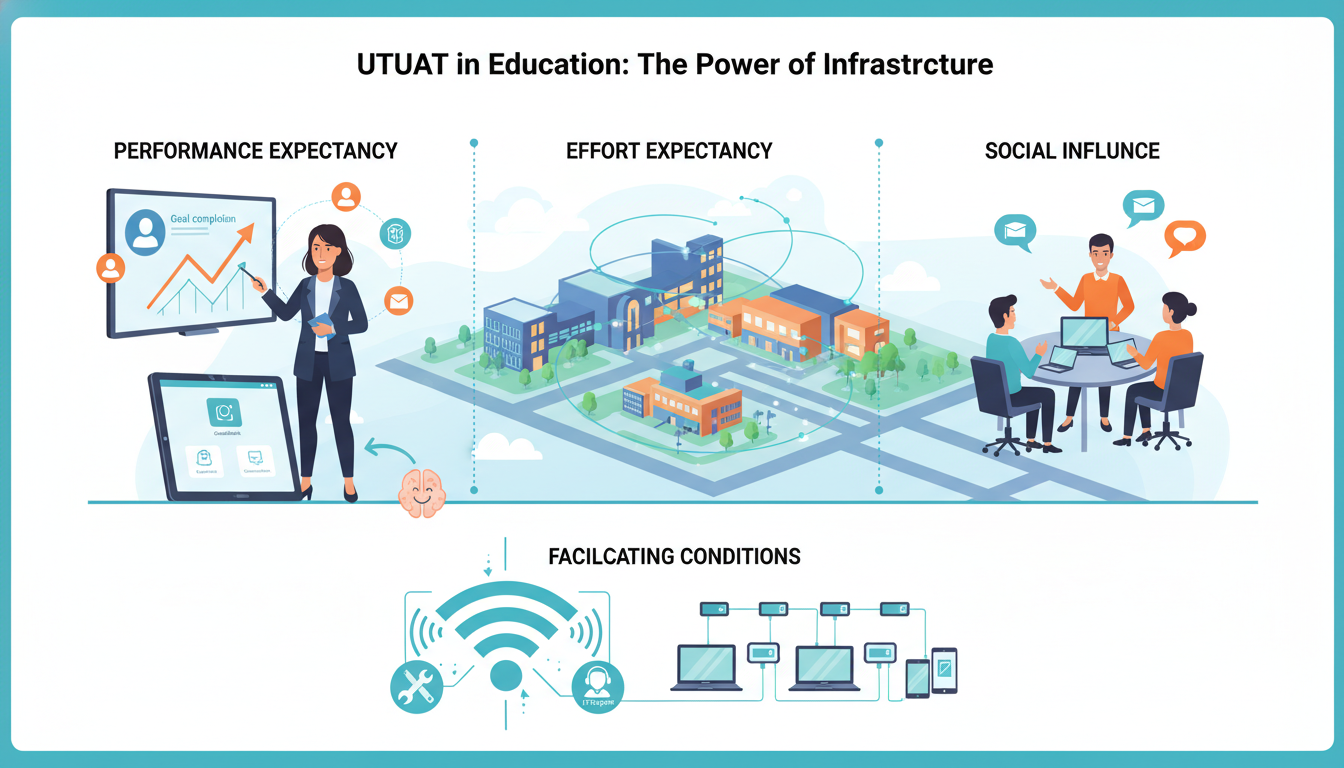

The Unification Paradigm: UTAUT and Its Application in Education

As the number of acceptance models proliferated—including the Motivational Model, the Model of PC Utilization, and the Diffusion of Innovations Theory—the field became fragmented. In 2003, Venkatesh et al. synthesized eight existing theories into the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). This model is widely considered the state-of-the-art in acceptance research, boasting an explanatory power of up to 70% of the variance in behavioral intention, compared to TAM’s typical 40%.

The Four Pillars of UTAUT in Educational Contexts

UTAUT replaces the PU/PEOU dichotomy with four broader constructs: Performance Expectancy, Effort Expectancy, Social Influence, and Facilitating Conditions. Each of these has distinct implications when applied to the school environment.

Performance Expectancy (PE)

Performance Expectancy is defined as the degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help him or her to attain gains in job performance. This is conceptually synonymous with PU but is broader, encapsulating extrinsic motivation and outcome expectations. In comparative studies of K-12 educators, PE consistently emerges as the strongest predictor of intention. Whether for a novice teacher struggling with remote instruction or a veteran integrating AI, the belief that the tool will work is the primary driver of adoption.

Effort Expectancy (EE)

Effort Expectancy captures the ease associated with the use of the system. In education, the significance of EE varies by demographic. For “digital native” students, EE is often a hygiene factor—expected but not a driver of delight. However, for older faculty or those with low digital self-efficacy, EE is a critical barrier. Research indicates that EE is a stronger predictor for women and older workers in the early stages of experience, highlighting the need for targeted training programs that reduce the perceived complexity for these demographic groups.

Social Influence (SI)

Social Influence is the degree to which an individual perceives that important others believe he or she should use the new system. Unlike TAM’s “Subjective Norm,” SI in UTAUT is explicitly moderated by age, gender, experience, and voluntariness. In the educational context, this construct captures the “isomorphism” of school districts—the pressure to adopt tools because neighboring districts have done so. It also captures the influence of students; if students demand the use of mobile devices or specific apps, teachers often feel compelled to adopt them to maintain engagement, effectively reversing the traditional hierarchy of influence.

Facilitating Conditions (FC): The Infrastructure of Learning

Perhaps the most critical addition in UTAUT is Facilitating Conditions—the degree to which an individual believes that an organizational and technical infrastructure exists to support use of the system. Crucially, UTAUT posits that FC influences Actual Use Behavior directly, bypassing Intention.

In education, this is the “make or break” variable. A teacher may intend to use VR (High PE, High EE, High SI), but if the school’s Wi-Fi bandwidth is insufficient or there are no IT staff to manage the headsets (Low FC), the behavior will not occur. This direct link to behavior makes UTAUT superior to TAM for analyzing resource-constrained educational environments, such as schools in developing nations or underfunded public districts. Research in South Africa regarding online learning adoption highlighted that without the facilitating condition of affordable data and reliable electricity, “intention” is irrelevant.

The Moderators: Voluntariness, Experience, Age, and Gender

One of UTAUT’s strengths is its inclusion of moderators that condition the relationships between constructs. In education, Voluntariness of Use is the most significant.

The Spectrum of Voluntariness

Educational technology adoption exists on a spectrum from purely voluntary (e.g., a teacher choosing to use Kahoot for review) to strictly mandatory (e.g., a university requiring grade submission via Blackboard). UTAUT predicts that Social Influence is significant only in mandatory settings, particularly for women and older workers in early stages of experience.

In mandatory settings, the dynamics of acceptance change. “Intention” becomes less about choice and more about compliance. In these cases, low Effort Expectancy does not lead to non-adoption (since adoption is forced) but rather to frustration, resistance, and burnout. Studies of electronic health records in teaching hospitals (a proxy for high-stakes mandatory ed-tech) show that when voluntariness is low, Facilitating Conditions and Effort Expectancy become the primary predictors of user satisfaction and stress.

UTAUT2: The Consumerization of Education

In 2012, Venkatesh et al. extended UTAUT to the consumer context (UTAUT2), adding Hedonic Motivation, Price Value, and Habit. This extension is increasingly relevant as education shifts toward a “student-as-consumer” model, particularly in higher education and lifelong learning sectors where students pay for access and have choices in their learning modalities.

Hedonic Motivation: Gamification and Engagement

Hedonic Motivation is defined as the fun or pleasure derived from using a technology. In the era of gamified learning (e.g., Duolingo, Minecraft Education), this construct has become a powerhouse predictor.

For K-12 students, Hedonic Motivation often eclipses Performance Expectancy. A study of mobile learning in mathematics found that Hedonic Motivation was the strongest predictor of behavioral intention, suggesting that for students, “engagement” is the proxy for “utility”. If the learning tool is boring, students will not use it voluntarily, regardless of its educational value. This contrasts with teachers, for whom utility remains paramount. This divergence necessitates a dual-design strategy for EdTech: interfaces must be “fun” for students (Hedonic) while “efficient” for teachers (Performance).

The “Price Value” Debate: Money vs. Time

Price Value is defined as the cognitive trade-off between the perceived benefits of the applications and the monetary cost of using them. Its application in education requires nuance depending on the stakeholder.

The Economic Cost for Students

In higher education, particularly in the Global South, Price Value is a literal barrier. The cost of data bundles required to access video lectures or download heavy e-textbooks is a significant determinant of adoption. Research in South African universities during the pandemic revealed that the high cost of data negatively impacted the Price Value perception, directly inhibiting adoption among lower-income students. Similarly, in contexts where students must purchase their own devices (BYOD policies), Price Value becomes a critical filter for equity.

The “Time Cost” for Teachers

In public K-12 education, software is often free to the teacher (paid for by the district). Consequently, early applications of UTAUT2 in education often dropped the Price Value construct. However, insightful recent research reinterprets Price Value as “Time Cost” or “Cognitive Load”.

The “price” a teacher pays is the time invested in learning the tool, setting it up, and troubleshooting it during class. If a VR headset takes 15 minutes to calibrate for a 45-minute lesson, the “Time Price” is too high relative to the pedagogical benefit. Teachers operate in a time-scarce economy; therefore, technologies that do not offer a distinct “Time Profit” (e.g., automated grading) are rejected due to poor Price Value, even if they cost zero dollars.

Habit: The Path to Institutionalization

Habit is defined as the extent to which people tend to perform behaviors automatically because of learning. In longitudinal studies, Habit has been shown to reduce the predictive power of other constructs over time. Once a student or teacher forms a habit of using an LMS to check assignments, they stop evaluating its Usefulness or Ease of Use; they simply do it.

This “Habit” construct connects UTAUT2 to Domestication Theory, which describes how technology moves from being a shiny novelty to an invisible part of the daily infrastructure. For educational administrators, the goal is to move usage from “Intention” (driven by PE/EE) to “Habit” (driven by automated behavior), at which point the technology is fully institutionalized.

The Core Dialectic: Meta-Analytic Perspectives on PU vs. PEOU

The tension between Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) is the central axis of technology acceptance research.

Determining which factor weighs more heavily is crucial for designing implementation strategies.

5.1 The Primacy of Usefulness

Meta-analyses across decades of research consistently demonstrate that Perceived Usefulness (PU) is the strongest predictor of behavioral intention in educational settings, significantly outweighing PEOU. The correlation coefficients for PU with usage behavior are consistently higher than those for PEOU (e.g., r=.63 for PU vs r=.45 for PEOU in seminal studies).

This finding reinforces the “Pedagogical Rationality” of teachers. Educators are willing to tolerate clunky interfaces, poor design, and steep learning curves if the tool provides a significant, tangible benefit to student learning or administrative efficiency. If a tool is incredibly easy to use but offers no pedagogical advantage over a pencil and paper, it will be discarded.

5.2 The Gatekeeper Hypothesis

While PU drives retention, PEOU acts as the causal antecedent. Regression analyses suggest that PEOU influences intention largely through its effect on PU. This “Gatekeeper Hypothesis” posits that if a system is too difficult, the user never reaches the threshold of experiencing its usefulness.

- Subject-Area Variance: The weight of these factors varies by discipline. Research suggests that STEM teachers, who often possess higher technical self-efficacy, may be more tolerant of low PEOU and focus almost exclusively on PU. In contrast, Humanities teachers may weigh PEOU more heavily, viewing technical friction as a greater barrier to their pedagogical goals.

- The Paradox of the Novice: For pre-service teachers (novices), PEOU is a stronger predictor of intention than for experienced in-service teachers. Novices, overwhelmed by the complexity of managing a classroom, prioritize tools that “don’t break,” whereas veterans prioritize tools that “teach well”.

5.3 Comparative Data on Predictor Strength

The following table synthesizes data from various meta-analyses regarding the relative strength of adoption predictors in educational settings.

| Predictor | Correlation with Intention (Approx.) | Primary Audience Relevance | Implications for Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | High (0.60 – 0.70) | Teachers, Administrators | Highlight student outcomes and efficiency gains in training. |

| Ease of Use (PEOU) | Moderate (0.30 – 0.50) | Students, Novice Teachers | Ensure intuitive UI; provide “sandboxes” for low-risk practice. |

| Social Influence | Variable (Low to High) | Mandatory contexts, Students | Leverage peer champions and administrative support. |

| Facilitating Conditions | High (Direct to Behavior) | Resource-constrained schools | Invest in Wi-Fi, support staff, and device availability before mandates. |

6. Critical Limitations: Why Models Fail in the Classroom

Despite the statistical robustness of TAM and UTAUT, a growing body of critical literature argues that these variance-based models are insufficient for capturing the sociotechnical complexity of education. They treat the classroom as a “black box” and the teacher as a solitary decision-maker, ignoring the systemic and material constraints of schooling.

6.1 The “Black Box” of Pedagogy and Beliefs

TAM treats technology adoption as a binary event: a user either adopts the tool or does not. It fails to account for how the tool is used or the quality of integration. A teacher might “accept” tablets (validating TAM) but use them only as expensive digital textbooks, a practice that offers no pedagogical advantage.

Furthermore, standard TAM models ignore Pedagogical Beliefs. Teachers hold deep-seated beliefs about how learning occurs (e.g., Constructivist vs. Transmissive). Research using the Teacher Technology Acceptance Model (T-TAM) has shown that these beliefs are filters for PU and PEOU. A constructivist teacher will perceive an open-ended creation tool (like Scratch) as highly useful, while a transmissive teacher might find it useless and chaotic. By ignoring these belief systems, standard TAM research fails to predict why certain “useful” tools are rejected by specific segments of the faculty.

6.2 Institutional Isomorphism and the Facade of Adoption

Schools are highly institutionalized environments subject to Isomorphism—the pressure to resemble other organizations to gain legitimacy. Institutional Theory suggests that schools often adopt technologies not because of rational PU calculations, but because of Mimetic Isomorphism: “The district next door bought iPads, so we must too, or parents will think we are behind”.

This administrative pressure forces teachers into “performative adoption,” where they use the technology when the principal is watching but revert to traditional methods otherwise. TAM’s “Social Influence” construct is too blunt to capture this dynamic, often conflating genuine peer support with coercive administrative isomorphism.

6.3 Sociomateriality: The Agency of Things

Critics utilizing Sociomateriality argue that TAM’s dualist ontology (User vs. Technology) is flawed. In a classroom, agency is not solely human; it is distributed across an assemblage of bodies, devices, cables, Wi-Fi signals, and furniture.

A teacher’s “refusal” to use a technology might not be a psychological rejection (low PU) but a material negotiation. If the classroom layout does not allow for charging 30 devices, or if the sunlight glares on the interactive whiteboard, the materiality of the room prohibits adoption. Sociomaterial perspectives reveal that “acceptance” is a continuous, emergent performance, not a static mental state that can be captured in a pre-survey.

6.4 The Intention-Behavior Gap

A pervasive methodological flaw in this field is the reliance on Behavioral Intention (BI) as a proxy for Actual Use (AU). Due to the difficulty of longitudinal tracking, most studies measure intention and assume it leads to behavior. However, the correlation is imperfect, creating an “Intention-Behavior Gap”.

This gap is often caused by the “Hypocrisy Effect” or social desirability bias—teachers report high intention to use “virtuous” educational tools to look good. Additionally, the gap is widened by unexpected barriers (Facilitating Conditions). A teacher may intend to use a tool, but a single network failure or a lost password can permanently derail that intention. Research shows that “one-time effort” to learn the tool is often the specific bottleneck between intention and action.

6.5 Teacher Burnout as a Barrier

Finally, standard models fail to account for the emotional economy of teaching. Teacher Burnout is a critical variable. A teacher suffering from emotional exhaustion may view even a highly useful and easy-to-use technology as a threat to their limited energy reserves. Recent studies integrating burnout measures suggest that high burnout negates the positive effects of PU and PEOU. Conversely, effective AI integration can reduce burnout by automating tasks, but only if the “learning tax” does not exacerbate existing stress.

7. Integrated Frameworks: T-TAM, TPACK, and Domestication

To address these limitations, the field has moved toward integrated models that blend TAM’s predictive structure with educational theory.

7.1 T-TAM: Contextualizing for Educators

The Teacher Technology Acceptance Model (T-TAM) expands the original framework to include constructs specific to the profession, such as Teacher Self-Efficacy and Pedagogical Beliefs.

- Key Findings: T-TAM studies indicate that general computer self-efficacy is less important than instructional self-efficacy. It is not enough to know how to use a computer; the teacher must believe they can manage a digital classroom.

- Validation: T-TAM has been validated as a robust instrument, showing that professional development focused on pedagogical integration (rather than just technical skills) is the strongest antecedent to PU and PEOU.

7.2 TPACK-TAM Integration

The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework describes the intersection of knowledge required for effective teaching. Integrating TPACK with TAM provides a powerful explanatory model.

- Antecedent Role: TPACK acts as an antecedent to TAM constructs. A teacher with high TPACK perceives technology as easier to use and more useful because they understand the pedagogical “why” behind the technical “how”.

- Mediation: Research indicates that PEOU mediates the relationship between TPACK and self-efficacy. A teacher’s deep knowledge (TPACK) lowers the perceived barrier of effort (PEOU), which in turn boosts their confidence (Self-Efficacy) to adopt.

7.3 Domestication of Technology

In contrast to the variance-based snapshot of TAM, Domestication Theory offers a qualitative lens, tracking how technology is “tamed” and incorporated into the daily routines and moral economy of the school.

- Process: It tracks the journey from Appropriation (acquisition) to Objectification (placement in the environment) to Incorporation (use in routines) and finally Conversion (becoming invisible).

- Relevance: This theory explains the “Habit” construct in UTAUT2. It reveals that successful adoption is not about constant excitement (Hedonic Motivation) but about the technology becoming boring, reliable, and invisible—part of the “furniture” of the classroom.

8. Strategic Implications and Future Outlook

The synthesis of these models offers clear, actionable guidance for educational leaders.

8.1 Strategic Recommendations

- Prioritize Pedagogical Value (PU): When selecting technology, marketing must focus on specific learning outcomes, not just “modernity.” Teachers are motivated by efficacy. Demonstrating that a tool improves student retention or reduces grading time is more effective than touting its innovative interface.

- Reduce the “Time Cost” (Price Value): Acknowledge that a teacher’s time is the currency of adoption.

Implementation plans must include “time subsidies”—periods where other duties are reduced to allow for learning the new tool. If the “Time Price” is too high, adoption will fail regardless of utility.

Invest in “Invisible” Infrastructure (FC): Facilitating conditions directly drive behavior. Investment in robust Wi-Fi, charging stations, and on-call IT support is not overhead; it is a direct driver of usage. The sociomaterial constraints of the classroom must be addressed before psychological attitudes can be leveraged.

Differentiated Training: Move away from “one-size-fits-all” professional development. Novices need training focused on Ease of Use (reducing anxiety), while veterans need training focused on Usefulness (pedagogical integration) and TPACK development.

Future Frontiers: AI and the Metaverse

The emergence of Generative AI (ChatGPT) and the Metaverse presents the next frontier for these models.

- AI Adoption: Early UTAUT2 studies on ChatGPT suggest that Performance Expectancy (efficiency) and Hedonic Motivation (novelty) are driving rapid student adoption. However, for teachers, Ethical Concerns (a variable not present in standard UTAUT) act as a massive negative moderator. Future models must incorporate “Perceived Ethical Risk” to predict AI acceptance.

- Metaverse Latency: For VR/Metaverse, Facilitating Conditions (hardware comfort, motion sickness) and PEOU are currently high barriers. Until the hardware becomes “invisible” (high PEOU), the Metaverse will remain in the “Appropriation” phase of domestication, failing to reach “Incorporation”.

In summary, while TAM and UTAUT provide the necessary statistical skeleton for understanding adoption, they must be fleshed out with the qualitative muscle of sociomateriality and the nervous system of pedagogical belief. Only by viewing the teacher not as a “user” but as a “pedagogical architect” operating within a constrained material ecosystem can we truly understand the complex dynamics of technology acceptance in education.