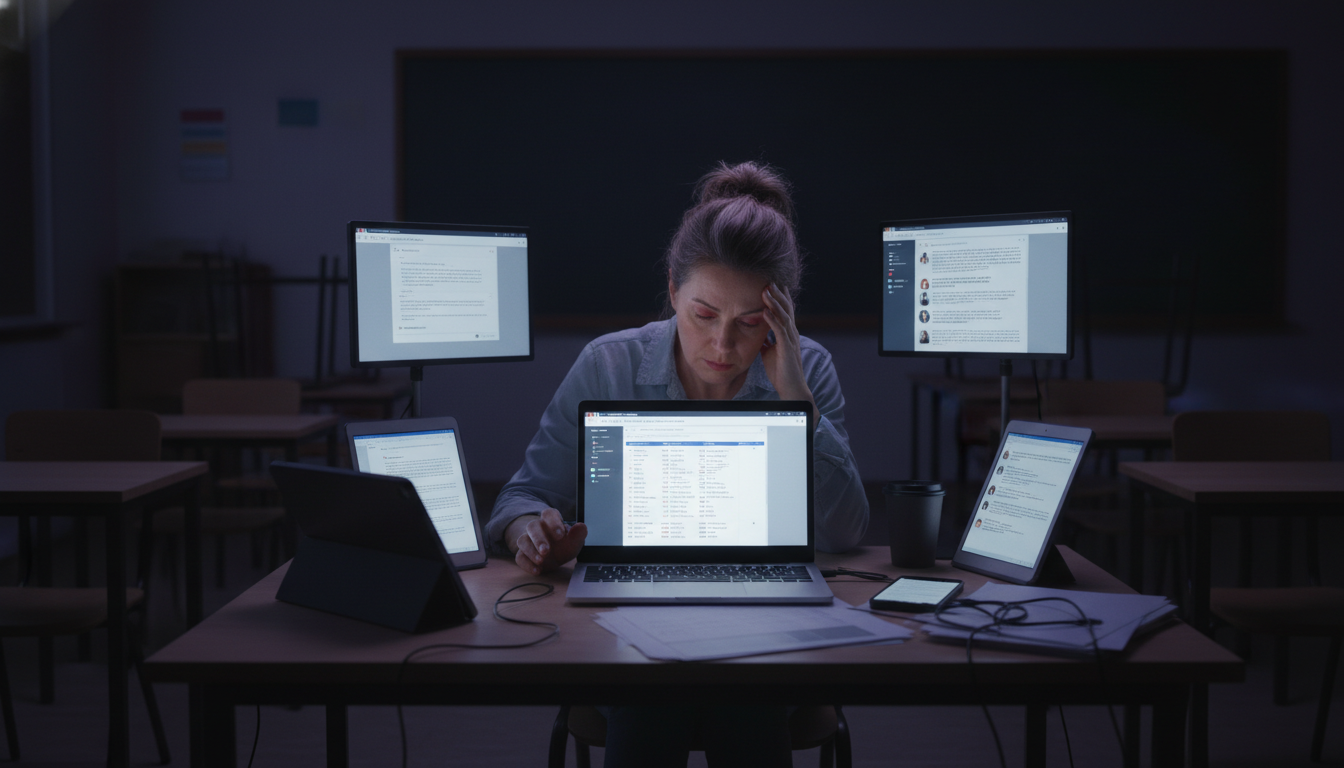

Teacher EdTech Abandonment: Workload, Stress & Burnout

Executive Summary

The digitization of the modern educational landscape has been characterized by a narrative of inevitable progress, efficiency, and personalization. Yet, beneath the surface of this technological acceleration lies a critical and counterintuitive phenomenon: the systematic abandonment of educational technology (EdTech) by the very educators most poised to champion it. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the structural, psychological, and economic factors driving “willing teachers”—those who are pedagogically skilled, open to innovation, and initially enthusiastic—to disengage from digital tools.

The central thesis of this investigation is that the integration of technology has inadvertently catalyzed a crisis of “invisible labor” and “negative return on effort.” While policy narratives often frame technology as a workload reducer, the empirical reality for the classroom teacher is frequently one of intensification. This report identifies three primary vectors of this intensification: the expansion of the “second shift” through digital grading and constant connectivity; the profound “emotional labor” required to bridge the gap between technological promise and infrastructural frailty; and the emerging burden of “algorithmic policing” in the age of Generative AI.

Synthesizing data from academic studies, teacher narratives, and industry analysis, this report maps the ecosystem of burnout. It argues that the “willing teacher” is not resisting innovation but is making a rational survival choice in the face of an unsustainable “effort expectancy.” Without a fundamental recalibration of how institutions value teacher time and emotional energy, the education sector risks a “hollowed-out” digital future, populated by tools but abandoned by the expert practitioners required to make them effective.

1. The Ecology of Teacher Workload in the Digital Era

1.1 The Expansion of the Working Day: Quantifying the “Second Shift”

The traditional conception of the teaching profession is bounded by the school bell, yet the digital era has systematically eroded these temporal boundaries, creating a profession that is effectively “always on.” The integration of Learning Management Systems (LMS), digital communication apps, and online grading platforms has not merely digitized existing tasks; it has expanded the volume and velocity of work required to maintain the educational ecosystem.

Research indicates that the grading workload alone has become a primary driver of attrition. On average, teachers spend 9.9 hours per week grading assignments, a figure that equates to more than a full extra workday every week. This labor is often performed outside of compensated contract hours, constituting a “second shift” that significantly encroaches on personal recovery time. Almost two-thirds (62%) of teachers identify grading as one of the worst aspects of their job, a sentiment exacerbated by digital platforms that facilitate a continuous, 24/7 stream of student submissions.

Unlike physical papers, which are constrained by the teacher’s ability to carry them, digital submissions have no physical limit. The psychological weight of an infinite digital queue creates a state of chronic “Techno-Overload,” where the teacher feels compelled to work faster and longer to keep pace with the machine. This phenomenon is not limited to grading; it extends to the “invisible” administrative tasks that technology was promised to automate but has instead multiplied.

| Traditional Task | Digital Equivalent | Workload Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Collecting Papers | Physical stack on desk; limited submission window. | LMS submissions (24/7); timestamps; file format compatibility checks. |

| Grading | Marginalia on paper; limited by physical space. | Digital comments; rubric clicking; voice notes; syncing grades to SIS. |

| Parent Updates | Quarterly report cards; scheduled phone calls. | Real-time app notifications (ClassDojo, Remind); daily email expectations. |

| Lesson Prep | Textbook review; photocopying. | Slide design; finding videos; checking links; creating digital interactives. |

The “willing teacher,” who is often the most dedicated to providing timely feedback, suffers disproportionately from this expansion. Their commitment to student success drives them to utilize every feature of the LMS—providing audio feedback, detailed annotations, and personalized rubric scores—thereby maximizing their own workload in a system that does not account for the time required to click through complex interfaces.

1.2 Administrative vs. Pedagogical Workload: The “Data Entry” Shift”

A critical distinction in understanding teacher burnout is the ratio of administrative labor to pedagogical labor. Teachers enter the profession to teach—to interact with students, facilitate learning, and foster growth. However, the digitization of schools has increasingly shifted the teacher’s role toward that of a data entry clerk or a mid-level systems administrator.

The “Administrative Creep” facilitated by technology is subtle but pervasive. Teachers report that digital tools often force a reallocation of time away from student interaction and toward data management. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, this shift accelerated. The role of the teacher was recalibrated to include managing remote learning logistics, troubleshooting connectivity issues for thirty students simultaneously, and ensuring digital compliance across multiple platforms.

This shift has profound implications for job satisfaction. When technology is experienced as an “administrative reform” rather than a pedagogical enhancement, it breeds resentment. For example, the implementation of complex “Workload Models” in higher education is often perceived not as a tool for equity, but as a bureaucratic exercise that consumes the very time it aims to measure. Teachers in high-performing systems still report excessive time spent on non-teaching activities, a trend exacerbated by the demands of personalized digital tracking.

The “willing teacher” often finds themselves in a paradoxical position: they want to use data to inform instruction (a pedagogical goal), but the friction of the tools requires them to spend hours manually transferring data between incompatible systems (an administrative burden). This “interoperability gap”—where the grading app doesn’t sync with the district gradebook—forces the teacher to become a “human API,” bridging the gap with manual data entry. This is low-value, high-effort work that contributes significantly to the feeling that technology is an impediment rather than an aid.

1.3 Invisible Labor and the “Setup Tax”

“Invisible labor” refers to the essential tasks required to make a system function that are unacknowledged, uncompensated, and often unseen by administration. In the context of EdTech, this labor is massive and is the primary reason why “plug-and-play” initiatives fail.

The Setup Tax: Every digital intervention carries a “transaction cost” in time. Before a single student learns a single concept, the teacher must pay the “Setup Tax.”

- Rostering: Manually creating accounts for 150 students across five different platforms.

- Curation: Vetting YouTube videos for inappropriate ads or dead links.

- Differentiation: Creating three different versions of a digital assignment to meet Individualized Education Program (IEP) requirements—a task that, while facilitated by tech, requires significant front-end loading.

- Self-Training: The hours spent watching tutorials or reading forums to understand a new software update, often done on weekends.

This labor is “invisible” because it does not appear on the lesson plan. An administrator observing a class sees a smooth 45-minute lesson using iPads. They do not see the three hours the teacher spent the night before ensuring the apps were updated, the logins were printed, and the Wi-Fi was stress-tested.

For the “willing teacher,” this invisible labor is often a labor of love—initially. They are willing to pay the tax because they believe in the outcome. However, when the “tax” becomes too high—when the setup time exceeds the instructional time—the economic calculation shifts. Teacher narratives reveal a breaking point where the “invisible” work becomes so overwhelming that it crowds out the “visible” work of teaching, leading to abandonment not out of malice, but out of necessity.

2. Emotional Labor and the Psychology of Technostress

2.1 Surface Acting and the “Happy Face” of Innovation

Teaching is an inherently emotional profession, requiring the constant management of feelings to create a safe, encouraging, and disciplined environment. This “emotional labor” is significantly intensified by the introduction of unreliable or complex technology.

The Performance of Confidence: When technology fails in the classroom—as it inevitably does—the teacher is placed in a position of vulnerability. The lesson flow is broken, students become distracted, and the teacher’s authority is threatened. To maintain control, the teacher must engage in “Surface Acting”—faking an emotion that is not genuinely felt.

- Scenario: An interactive whiteboard freezes during a critical explanation. The teacher feels rising panic, frustration, and embarrassment.

- The Act: The teacher smiles, makes a joke (“The ghosts in the machine are active today!”), and calmly redirects students to a backup activity.

- The Cost: This suppression of genuine emotion consumes significant psychological resources. Research links habitual surface acting directly to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, the two core components of burnout.

For “willing teachers,” there is an added layer of “Deep Acting”—attempting to actually align their internal feelings with the institutional goal.

They may force themselves to feel enthusiastic about a new district-mandated app (“I need to be a team player, this will be great for the kids”), even when their professional judgment tells them it is flawed. This constant realignment of the self to fit the system’s demands is exhausting and unsustainable.

The Five Dimensions of Technostress

The psychological burden of technology is not a vague “stress” but a specific, measurable phenomenon known as “Technostress.” Research identifies five distinct “creators” of technostress that are pervasive in the teaching profession. These dimensions explain why even competent teachers feel overwhelmed.

| Dimension | Definition | Scale Item Examples | Impact on “Willing Teachers” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Techno-Overload | The compulsion to work faster and longer due to technology. | “I am forced by this technology to do more work than I can handle.” | High performers often take on the burden of piloting new tools, exacerbating their own overload. |

| Techno-Invasion | The encroachment of work into personal life; the “always-on” culture. | “I feel that my personal life is being invaded by this technology.” | Enthusiastic teachers often check emails and notifications late at night, eroding recovery time. |

| Techno-Complexity | The feeling that one’s skills are inadequate due to constant complexity. | “I need a long time to understand and use new technologies.” | Even tech-savvy teachers struggle when distinct platforms do not integrate (interoperability issues). |

| Techno-Insecurity | The fear of being replaced by technology or younger, tech-native colleagues. | “I feel threatened by coworkers with newer technology skills.” | Creates a competitive rather than collaborative culture, reducing peer support networks. |

| Techno-Uncertainty | The stress caused by constant changes and upgrades to systems. | “There are constant changes in computer software in our organization.” | Constant updates (e.g., LMS interface changes) render lesson plans and tutorials obsolete overnight. |

The “Willing Teacher” Vulnerability: Paradoxically, the “willing teacher” scores higher on certain dimensions of technostress precisely because they care. A teacher who is indifferent to student outcomes is less stressed by Techno-Uncertainty; if the lesson fails, they don’t care. The willing teacher, who has planned a meticulous lesson, experiences high anxiety (Uncertainty) because they have a high stake in the lesson’s success. The “glitch” is not just a technical failure; it is a pedagogical failure that they take personally.

The Erosion of “Care Work”

A profound source of emotional distress is the perception that technology interferes with “care work“—the fundamental human connection that draws people to teaching. Teachers describe the “invisible labor” of caring, which involves managing student anxieties, ensuring equity, and fostering relationships.

Screens as Barriers: Teachers report that heavy technology use creates a physical and psychological barrier. Eye contact—the primary tool for “reading the room” and gauging understanding—is replaced by the tops of heads staring at screens. This loss of non-verbal feedback leaves expert teachers feeling “blind” and ineffective.

Furthermore, EdTech often commodifies feedback, turning nuanced, human interaction into data points on a dashboard. When teachers feel they are becoming “administrators of software” rather than “nurturers of potential,” the emotional return on their labor collapses. They experience a form of “alienation” from their own craft, where the tool that was supposed to connect them to students instead mediates and distances the relationship.

Perceived Return on Effort (ROE): The Economics of Abandonment

The Effort Heuristic: Calculating the Cost of Innovation

The decision to adopt or abandon a technology is often an intuitive economic calculation of “Perceived Return on Effort” (ROE). This concept, grounded in the “Effort Heuristic,” suggests that individuals judge the value of an outcome based on the effort required to achieve it.

For teachers, the “Input” is time and cognitive energy. The “Output” is student learning, engagement, or workflow efficiency.

- The Optimism Bias: “Willing teachers” initially have a high “Performance Expectancy” (PE)—they believe the tool will help them significantly. This optimism leads them to invest heavily in the setup phase (Front-End Loading).

- The Reality Check: Abandonment occurs when the “Break-Even Point” is never reached. If a teacher spends 5 hours setting up a gamified lesson (Input) and the students are engaged for only 20 minutes before losing interest or finding a workaround (Output), the ROE is negative.

Effort Expectancy (EE) vs. Performance Expectancy (PE): The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) posits that adoption is driven by PE and EE. Research shows that for experienced teachers, PE is the stronger predictor of use. They need to know it works. For newer teachers, EE (ease of use) is more critical. “Willing teachers” often abandon tools not because they are “hard to use” (high EE), but because they ultimately do not improve learning outcomes (low PE) relative to the time invested.

Case Studies of Abandonment: Why Specific Tools Fail

Analysis of teacher narratives and qualitative studies reveals consistent patterns in why specific types of tools are abandoned.

-

The Flipped Classroom:

- The Promise: Students watch lectures at home, freeing up class time for active learning.

- The Reality: Creating high-quality video content consumes immense amounts of teacher time (editing, recording). Furthermore, a significant percentage of students do not watch the videos at home due to lack of access or motivation.

- The Abandonment Logic: The teacher arrives in class and realizes they must re-teach the content anyway. The 5 hours spent editing the video was “wasted effort.” The teacher returns to in-class instruction to ensure equity and coverage.

-

Gamification (e.g., ClassDojo, Duolingo):

- The Promise: High engagement through points, badges, and leaderboards.

- The Reality: The “novelty effect” wears off quickly. Students begin to demand external rewards for basic behaviors (“Do I get a point for sitting down?”). The teacher finds themselves managing a “token economy” rather than teaching content.

- The Abandonment Logic: Teachers realize the tool is fostering extrinsic compliance rather than intrinsic motivation. The distraction of managing the “points” outweighs the engagement benefit. Teachers abandon the app to reclaim the “pedagogical focus”.

-

Interactive Notebooks (Digital or Physical):

- The Promise: Creative, personalized student portfolios.

- The Reality: The time spent on formatting (cutting, pasting, digital layout) consumes the majority of the lesson. “We spent 20 minutes formatting the slide and 5 minutes on the science.”

- The Abandonment Logic: The “cognitive load” of the activity is focused on the tool/process, not the subject matter. The teacher stops using the notebooks to focus on the actual curriculum.

The “Enthusiastic” Teacher Trap

Paradoxically, the teachers most likely to abandon technology are often those who were most enthusiastic initially. These “innovators” invest heavily in “deep integration“—attempting to use technology to transform pedagogy rather than just digitize worksheets.

However, “transformational” use requires significantly more infrastructure and support than “substitution” use. When the infrastructure (Wi-Fi, device reliability) fails, the “willing teacher” falls harder because their investment was greater. They experience “moral injury“—a sense that their dedication was betrayed by a system that set them up to fail. The indifferent teacher who never logged in lost nothing. The willing teacher who spent their weekend building a digital escape room that crashed lost everything.

The AI Disruption: A New Era of Workload and Policing

From Grading to Policing: The Sociological Shift

The emergence of Generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT) has introduced a tectonic shift in the teacher’s role, moving them from “Assessor” to “Forensic Investigator.” While EdTech proponents argue that AI saves time on lesson planning—with some pilots reporting a 40% reduction in planning time—it has simultaneously created a massive new burden in the assessment phase.

The Burden of Suspicion: Teachers now view student submissions with a baseline of suspicion. The workflow has shifted from “reading for understanding” to “reading for detection.”

- The Investigation Workflow: Read the essay -> Notice a lack of “voice” -> Run through AI detector -> Check Google Docs version history -> Compare to writing samples -> Confront student.

- The Time Cost: One study noted that this “AI fact-checking” process took 158% longer than the traditional grading process.

- The Statistics: A survey indicates that 64% of discipline cases now involve AI-related plagiarism. The sheer volume of these cases represents a massive administrative and emotional sinkhole for teachers.

Cognitive Load and the “Reviewer” Burden

Even when AI is used “legitimately” by the teacher (e.g., to generate lesson plans or quizzes), it shifts the cognitive load.

- Prompt Engineering: Writing effective prompts is a skill that requires iteration and cognitive effort.

- The Verification Tax: AI “hallucinates” (invents facts). A teacher cannot simply print an AI-generated lesson plan; they must meticulously fact-check every line. This creates a “Reviewer Burden.”

- The Paradox: Teachers report that it is often faster to write the lesson plan from scratch (a creative, “flow state” activity) than to generate, read, verify, correct, and format AI output (a high-focus, tedious activity).

The “time-saving” promise evaporates under the weight of verification.

4.3 The Erosion of Trust and the Adversarial Classroom

The most damaging aspect of the AI era is the erosion of the teacher-student alliance. When teachers are forced to police every assignment, the “relational trust” that buffers against burnout is destroyed.

- False Positives: AI detection tools are notoriously unreliable, often flagging innocent students (especially English Language Learners). The emotional labor of accusing a student, meeting with parents, and navigating the disciplinary bureaucracy is immense.

- The Loss of Joy: Teachers report that policing AI use diverts energy away from teaching and feedback, turning the classroom into an adversarial environment. This loss of the “joy of teaching” is a critical factor in the attrition of educators who value connection over content delivery.

5. The “Willing Teacher” Profile: Who Leaves and Why?

5.1 The Conscientiousness Trap

Research into teacher personality traits suggests that those most susceptible to burnout are often the most conscientious. These teachers care deeply about their students and set high standards for themselves. They are the “canaries in the coal mine.”

- The “Over-Functioning” Trap: When the technology fails (e.g., the Wi-Fi drops), the conscientious teacher “over-functions” to compensate. They use their own data plan; they bring their own laptop; they print backup packets “just in case.” This over-functioning is physically and emotionally unsustainable.

- Moral Injury: When they are forced to use tech that they perceive as harmful (e.g., invasive proctoring software or addictive gamification), they feel a violation of their professional ethics. Their abandonment is a moral stance.

5.2 The Narrative of “Quitting”

The “Teacher Quit” narrative on social media (e.g., #TeacherQuitTok) reveals that technology is often the “tipping point.” It is rarely the sole cause, but it is the accelerant. The accumulation of “micro-stressors”—the login that fails, the printer that jams, the AI that cheats, the parent email at 10 PM—creates a cumulative load that eventually breaks the teacher’s resilience. The “willing teacher” quits the technology to save their teaching—or they quit teaching to save themselves.

6. Systemic Factors: Institutional Betrayal

6.1 The “Shadow Work” of IT Support

In many schools, formal IT support is slow or non-existent at the point of need. This creates a reliance on “Shadow IT Support.”

- The Peer Tax: The “tech-savvy” willing teacher becomes the unpaid help desk for their entire department. They spend their planning periods troubleshooting colleagues’ projectors and resetting passwords. This “shadow work” eats into their own preparation time and emotional reserves, leading to faster burnout for the most capable staff.

6.2 Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up: The Agency Gap

Many EdTech initiatives fail because they are imposed from the top down without teacher consultation. “Techno-Insecurity” arises when teachers feel they have no agency in choosing the tools they use.

- Vendor-Driven Decisions: Administrators often purchase software based on “dashboards” and “compliance,” not “usability” or “pedagogy.”

- The Implementation Gap: Teachers are handed a tool and told to “integrate it.” There is no discussion of why or how. This lack of agency breeds resistance. Even willing teachers resent being treated as “end-users” rather than “professionals”.

7. Conclusions and Pathways Forward

The evidence presented in this report suggests that the EdTech sector and educational administration have fundamentally misunderstood the nature of teacher work. By viewing teaching as a series of “tasks” to be optimized, they have neglected the human, emotional, and relational core of the profession.

The “Slow EdTech” Alternative: To retain “willing teachers,” a shift is needed toward “Slow EdTech”—a deliberate, reflective approach to adoption. This movement advocates for:

- Pedagogy First: Prioritizing pedagogical values (fairness, care) over economic rationality (speed, efficiency).

- Reliability Over Novelty: Choosing tools that work seamlessly (High ROE) over tools that promise revolution but deliver complexity.

- Ethical Pause: Taking time to evaluate the ethical implications of tools (e.g., AI) before rolling them out.

Recommendations for Retention:

- Audit “Invisible Labor”: Districts must conduct time audits to measure the actual time required for digital tasks and compensate or reduce workload accordingly.

- Restore Boundaries: Enforce “right to disconnect” policies that protect teachers from the “Techno-Invasion” of 24/7 communication.

- Human-Centric AI Policy: Shift the focus from policing cheating to assessing process, reducing the adversarial burden on teachers.

- Support Agency: Give teachers a voice in tool selection and recognize their role as “pedagogical experts,” not just “users.”

Ultimately, technology must serve the teacher, not the other way around. Until the “Return on Effort” turns positive, “willing teachers” will continue to exercise their ultimate agency: the choice to opt out.