Empowering Senior Teachers: Bridging Tech & Wisdom in Education

The Generational Paradox in Educational Technology

The contemporary educational landscape is marked by a profound paradox: the educators possessing the deepest reservoirs of pedagogical expertise—senior teachers with decades of classroom experience—are often those most marginalized by the rapid integration of educational technology. This “digital divide” within faculty rooms is not merely a matter of technical proficiency; it is a complex sociopsychological phenomenon rooted in professional identity, risk aversion, and the systemic devaluation of analog wisdom.

For schools to successfully navigate digital transformation, they must move beyond the reductive narrative that positions veteran teachers as “resistors” or “luddites.” Instead, leadership must recognize that resistance is often a rational defense mechanism employed by experts who perceive current technological implementations as a threat to instructional quality. Senior teachers operate at a level of unconscious competence in their traditional methodologies; the sudden imposition of digital tools forces them back into a state of conscious incompetence, creating anxiety and a fear of professional devaluation.

The objective of this report is to provide an exhaustive analysis of strategies to bridge this gap. By leveraging frameworks such as the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM), the TPACK framework, and the Knoster Model for Managing Complex Change, and by applying principles of Andragogy (adult learning), schools can transform the dynamic from one of “compliance” to one of “co-creation.” The ultimate goal is not simply to get senior teachers to use technology, but to have them infuse technology with their pedagogical wisdom, thereby enhancing the educational experience for all students.

The Psychology of Resistance: Fear of Devaluation and Risk Aversion

To facilitate change, one must first understand the psychological underpinnings of resistance. Research indicates that resistance among senior staff is frequently driven by emotional responses including feeling overwhelmed, fear of job security, and ideological conflicts regarding the nature of “quality” education.

Risk Perception and Professional Identity

Teachers’ beliefs about instruction are deeply intertwined with their subject-area identity. A chemistry teacher with 25 years of experience does not just teach “science”; they teach a specific, curated understanding of the physical world. When a new technology is introduced, it introduces a variable of uncertainty. For a novice teacher, a “failed” lesson due to a tech glitch is a learning experience. For a veteran teacher, whose professional self-concept is built on mastery and control, a visible failure in front of students is a profound threat to their authority and dignity.

This risk aversion is compounded when the technology is perceived as “unproven.” Veteran teachers view their students’ outcomes as the highest stake. They are ethically hesitant to gamble student learning on tools that may be flashy but pedagogically shallow. Consequently, resistance is often a form of quality control—a refusal to lower standards for the sake of novelty.

The “Expertise Trap”

The “Expertise Trap” suggests that the more expert a teacher is in an analog method (e.g., Socratic seminar, handwriting analysis), the higher the psychological “switching cost” to a digital alternative. The veteran teacher loses more efficiency than a novice does when switching to a digital platform, because their analog efficiency was so high. Therefore, the “value proposition” of the technology must be significantly higher for a veteran than for a new teacher to justify the transition.

The Cost of the Divide

Failing to address this divide creates a bifurcated school culture. On one side are the “innovators,” often younger staff who are tech-fluent but may lack classroom management finesse. On the other are the “veterans,” who possess deep pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) but are isolated from digital workflows. This polarization prevents the transfer of knowledge. Novice teachers fail to learn the timeless art of teaching from veterans because they view them as “outdated,” while veterans fail to adopt efficiency-enhancing tools because they view them as “fads”.

Successful digital transformation requires retaining senior staff. Their departure leads to a “brain drain” of institutional memory and mentorship capacity. Thus, the challenge for leadership is to implement support structures that honor the veteran’s past contributions while equipping them for the future.

Theoretical Frameworks for Change Management in Education

Effective intervention requires a theoretical basis to diagnose the root causes of friction and prescribe appropriate support. Three frameworks—TPACK, CBAM, and the Knoster Model—provide the necessary scaffolding for this analysis.

The TPACK Framework: Validating Pedagogical Content Knowledge

The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework is essential for reframing professional development (PD) for senior teachers. It identifies three primary forms of knowledge:

- Content Knowledge (CK): The subject matter (e.g., Calculus, European History).

- Pedagogical Knowledge (PK): The instructional methods (e.g., inquiry-based learning, classroom management).

- Technological Knowledge (TK): The technical skills (e.g., using an LMS, interactive whiteboards).

The Missing Link: TPK

Traditional PD often focuses exclusively on TK—teaching teachers “how to click.” This is insulting to veteran teachers who already possess high CK and PK. The strategy must be to focus on Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK)—the understanding of how technology changes teaching.

By acknowledging that the veteran teacher is already an expert in Content and Pedagogy, the facilitator can frame technology not as a replacement, but as an extension of their existing expertise. Research confirms that when PD is grounded in TPACK, teachers report higher self-efficacy because the technology is contextualized within their subject area expertise.

- CK (Content): Knowledge of the subject matter. High Strength. Veterans are often subject-matter experts.

- PK (Pedagogy): Knowledge of how to teach. High Strength. Veterans have mastered classroom dynamics.

- TK (Tech): Knowledge of digital tools. Perceived Weakness. Source of anxiety.

- TPK (Tech + Pedagogy): Understanding how tools impact teaching strategies. The Growth Zone. Connecting tools to existing teaching strategies.

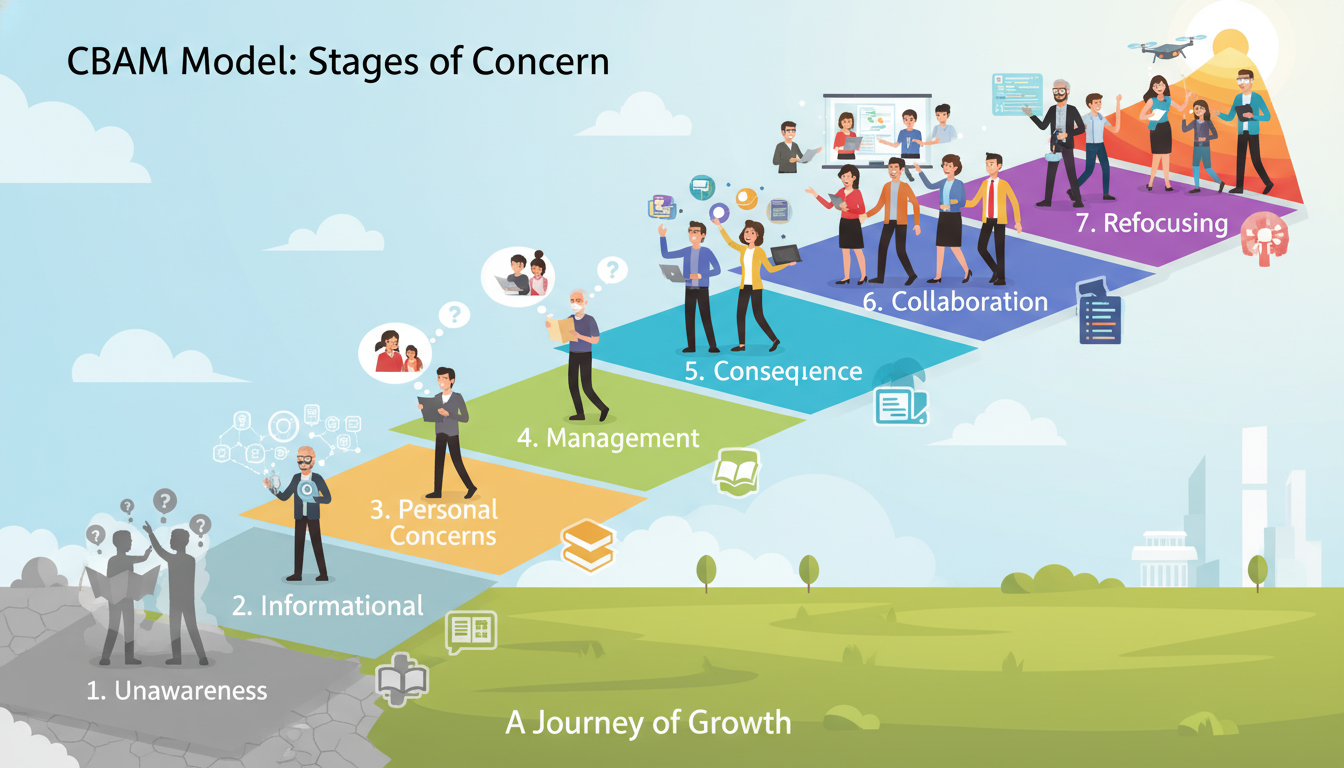

The Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM)

The Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) shifts the focus from the innovation to the individual. It posits that teachers move through predictable “Stages of Concern” as they adopt a new practice. Understanding a senior teacher’s stage is critical for tailoring support.

Diagnosing the Stage of Concern

Most resistance arises when administrators try to address “Impact” concerns (Stage 4-6) while the teacher is still struggling with “Management” concerns (Stage 3).

- 0. Awareness (Unconcerned)

Typical Statement from Senior Teacher: “I’m not sure what this new initiative is about.”

Required Support Strategy: Communication: Share low-stakes information. Avoid hype.

- 1. Informational (Self)

Typical Statement from Senior Teacher: “I would like to know more details about the requirements.”

Required Support Strategy: Clarity: Provide clear, written documentation.

- 2. Personal (Self)

Typical Statement from Senior Teacher: “How will this affect my workload? Will I look incompetent?”

Required Support Strategy: Reassurance: Address time demands. validate fears.

- 3. Management (Task)

Typical Statement from Senior Teacher: “I spend all my time fixing passwords and printers.”

Required Support Strategy: Technical Support: Rapid response “break-fix” help. Student Help Desk.

- 4. Consequence (Impact)

Typical Statement from Senior Teacher: “Is this actually helping my students learn better?”

Required Support Strategy: Evidence: Show data connecting tech to outcomes.

- 5. Collaboration (Impact)

Typical Statement from Senior Teacher: “How can I work with others to improve this?”

Required Support Strategy: Peer Mentoring: Teacher Design Teams (TDTs).

- 6. Refocusing (Impact)

Typical Statement from Senior Teacher: “I have an idea to modify this tool for better results.”

Required Support Strategy: Co-Creation: Empower them to lead innovation.

Insight: Senior teachers often get stuck at Stage 3 (Management). If the technology is unreliable, they never progress to considering its pedagogical value. Therefore, reliable infrastructure is a prerequisite for pedagogical buy-in.

The Knoster Model for Managing Complex Change

The Knoster Model identifies five critical elements required for successful change: Vision, Skills, Incentives, Resources, and Action Plan. The absence of any single element leads to a specific, predictable negative outcome.

Application to Senior Teachers:

- 1. Vision: (Missing = Confusion). Senior teachers have seen initiatives come and go. If the vision is just “modernization,” they will wait for it to pass. The vision must be “improving student equity” or “deepening inquiry”.

- 2. Skills: (Missing = Anxiety). This is the most common barrier. Anxiety paralyzes the veteran teacher who fears public failure. Skill building must be safe and private.

- 3. Incentives: (Missing = Resistance). Incentives are not necessarily monetary. For veterans, the incentive is often “saving time” or “reaching the disengaged student.” If the tech adds work without a payoff, resistance is rational.

- 4. Resources: (Missing = Frustration). Resources include hardware, software, and time. Unfunded mandates generate immediate frustration.

- 5. Action Plan: (Missing = False Starts). Without a clear timeline and steps, the initiative feels like a treadmill—lots of movement, no progress.

Strategic Insight: When a senior teacher resists, use Knoster as a diagnostic.

Ask: “Are they confused (Vision), anxious (Skills), or frustrated (Resources)?” Treat the resistance as a symptom of a missing organizational element, not a personal flaw.

2.4 The ADKAR Model

Complementing Knoster, the ADKAR model (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, Reinforcement) emphasizes Desire. For senior teachers, Desire is rarely intrinsic to the technology itself. It must be manufactured by connecting the technology to a problem they want to solve.

- Awareness: “We are moving to Canvas.”

- Desire: “Canvas will automatically grade your quizzes, saving you 3 hours a week.” (Connecting to personal benefit).

3. Andragogy: Respecting the Adult Learner

Effective professional development for senior teachers must be grounded in Andragogy (the method and practice of teaching adult learners), distinct from Pedagogy (teaching children).

3.1 Principles of Andragogy for Veteran Staff

1. Self-Concept and Autonomy

Adults need to be responsible for their own decisions. “Mandatory” one-size-fits-all training violates their self-concept as autonomous professionals.

- Strategy: Offer a “menu” of technology options. Instead of “Everyone must use Quizlet,” the directive should be “Everyone must implement one digital formative assessment tool. Here are three options, or you may propose your own”.

2. The Role of Experience

Adults come to the learning activity with a volume and quality of experience that is a rich resource for learning.

- Strategy: PD sessions should be discussion-based, not lecture-based. Ask veteran teachers to map the new technology onto their existing mental models. “How is this Google Doc collaboration similar to the group posters you used to do? How is it different?”.

3. Readiness to Learn (Relevance)

Adults become ready to learn those things they need to know effectively to cope with real-life situations.

- Strategy: Just-in-Time Learning. Do not teach gradebook software in August if they won’t use it until October. Teach it the week grades are due. Contextual relevance drives retention.

4. Problem-Centered Orientation

Adults are problem-centered rather than subject-centered.

- Strategy: Organize workshops around problems, not tools.

- Bad Title: “Introduction to Google Sheets.”

- Good Title: “Solving the Permission Slip Nightmare: Tracking Forms in 5 Minutes”.

3.2 Differentiating Professional Development

Just as teachers differentiate for students, leaders must differentiate for staff. A “track” system respects the varying levels of readiness among senior staff.

| Track | Target Audience | Focus | Facilitation Style |

|---|---|---|---|

| Track A: Essentials | High Anxiety / Low Skill | “Tech for Efficiency” (Email, Attendance, basic LMS). | High-touch, slow-paced, printed guides. Focus on reducing workload. |

| Track B: Integration | Moderate Skill | “Tech for Instruction” (Digital assessments, collaboration tools). | Collaborative, workshop-style, peer-led. |

| Track C: Innovation | Early Adopters | “Tech for Transformation” (AI, VR, Global Projects). | Self-directed, project-based, exploration. |

Insight: Allowing senior teachers to self-select into “Track A” removes the shame of being “behind” and provides a safe environment to build foundational competence without slowing down the early adopters.

4. Co-Creation and Participatory Design

One of the most effective strategies to mitigate resistance is to involve veteran teachers in the design phase of technology integration. When teachers are co-creators, they move from being objects of change to agents of change.

4.1 Teacher Design Teams (TDTs)

Teacher Design Teams are collaborative groups where teachers work together to design curricular materials, lessons, or assessments. By integrating senior teachers into TDTs focused on technology, schools leverage their PCK while upskilling them in TK.

Mechanism of Action:

In a TDT, a senior teacher might be paired with a tech coach and a novice teacher.

- The Senior Teacher’s Role: Define the learning outcome and the pedagogical rigor. “Students need to understand the causal relationship in this historical event.”

- The Tech Coach’s Role: Propose digital tools that support that rigor. “We could use a digital timeline builder or a causal loop diagramming tool.”

- The Outcome: The technology is selected because it serves the senior teacher’s pedagogical goal. This validates their expertise and ensures the technology is “pedagogically sound”.

Case Study Success: Research indicates that TDTs promote knowledge sharing and significantly improve TPACK scores among participants, as the learning is situated in the actual work of curriculum design rather than abstract training.

4.2 Participatory Design in Technology Planning

Participatory design (PD) involves stakeholders in the development of the tools they will use. This is crucial for avoiding “usability failure” where expensive software is purchased but never used because it doesn’t fit the classroom workflow.

The “Skeptic Champion” Strategy:

Deliberately include the most vocal senior skeptic on the technology selection committee.

- Why: If a tool satisfies the skeptic, it will likely work for everyone.

- Benefit: The skeptic feels heard and respected. If they approve the tool, they become its most credible advocate to other senior staff (“If Mrs. Smith likes it, it must be good”).

- Risk Mitigation: Ensure the committee has a clear rubric that values both innovation and pedagogical utility, so the skeptic cannot simply block progress but must evaluate based on criteria.

5. Mentoring Models: From Hierarchy to Reciprocity

Traditional “expert-novice” mentoring often alienates senior teachers when the “expert” is a 24-year-old tech coach. Effective mentoring for this demographic must be bidirectional and reciprocal.

5.1 Cognitive Coaching

Cognitive Coaching is a non-judgmental mediation of thinking. It assumes the teacher has the resources to solve their own problems and uses questioning to unlock those resources. It is high-respect and low-directive.

The Protocol:

Instead of saying “You should use X,” the coach asks mediating questions:

- Planning: “What are your goals for this lesson?”

- Problem ID: “What barriers might prevent students from reaching those goals?”

- Possibility: “If you had a tool that could remove that barrier, what would it look like?”

- Connection: “I know a tool that matches that description. Would you be open to exploring it?”

Why it works for Seniors: It positions the teacher as the decision-maker. The coach is merely a resource provider, preserving the teacher’s autonomy and status.

5.2 Reverse Mentoring

Reverse mentoring flips the traditional hierarchy, assigning a younger employee to mentor a senior executive or teacher on technology and cultural trends. This model has been successfully deployed in corporations like General Electric and Citibank to bridge generational gaps.

Structuring for Success in Schools:

To avoid condescension, the relationship must be defined as Reciprocal Mentoring or Skill Swapping.

- The Exchange: The younger teacher mentors on digital tools (e.g., social media trends, specific apps). The senior teacher mentors on institutional navigation or pedagogical strategies (e.g., parent communication, classroom management).

- Training: Younger mentors must be trained in emotional intelligence and “facilitation language” to avoid making the senior teacher feel inadequate.

Case Study – General Electric: GE used reverse mentoring to help senior leaders understand digital transformation. The key was that the junior mentors were empowered to share perspectives—not just technical instructions—fostering a culture of mutual respect and reducing the fear of asking “stupid questions”.

5.3 Peer Coaching: “Colleague Connect”

Peer coaching involves teachers observing and supporting one another in a non-evaluative capacity. Platforms or internal systems can facilitate “Colleague Connect” matches based on complementary strengths.

The “Partner” Model:

- Matching: Pair a senior teacher strong in “Formative Assessment” with a teacher strong in “Digital Quiz Tools.”

- The Contract: They agree to observe each other once a month with a specific focus. The senior teacher critiques the questions in the digital quiz (rigor), while the partner critiques the setup of the quiz (technical).

- Outcome: Both parties improve. The senior teacher learns the tool; the junior teacher learns how to write better questions.

5.4 Student-Led Help Desks: The Burlington Model

A significant barrier for senior teachers is the fear of technical failure during class. The “Student-Led Help Desk” model transforms this liability into an asset.

Case Study: Burlington High School (MA)

Burlington High School implemented a student-run help desk where students earn credit to serve as Tier 1 tech support.

- Mechanism: Students are stationed in a “Genius Bar” setting or can be dispatched to classrooms.

- Impact on Senior Teachers: It removes the burden of troubleshooting. If a projector fails or an iPad won’t connect, the teacher calls a student. The teacher can continue teaching while the student fixes the tech.

- Cultural Shift: This lowers the stakes for the teacher. They don’t have to be the “tech expert”; they just have to be the “lead learner.” It creates a community where students and teachers rely on each other.

6. Facilitation Language: The Linguistics of Respect

The language used by coaches and facilitators is a critical determinant of success. “Elderspeak” or condescending simplification can instantly trigger resistance.”

6.1 Reflecting on Facilitation Language

Facilitators must reflect on their language to ensure it conveys dignity.

Avoiding Deficit Language:

- Avoid: “I know this is hard for you,” “It’s so easy, just look,” or “Let me do it for you.”

- Use: “This software design is quite complex,” “Let’s navigate this together,” or “You drive, I’ll navigate.”

The Power of Analogy:

When teaching abstract digital concepts, use analogies grounded in the physical world (a core Andragogical strategy).

- The Cloud: Compare to a bank vault—you can deposit money (data) in one branch and withdraw it from another; the money isn’t “in” the teller’s pocket.

- Folders/Directories: Compare to physical filing cabinets and manila folders.

6.2 Asset-Based Coaching Stems

Coaches should use sentence stems that presume competence and invite the teacher to apply their existing judgment to the new tool.

| Intent | Deficit-Based Stem (Avoid) | Asset-Based Stem (Use) |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosing | “What are you struggling with?” | “What is currently interrupting your workflow?” |

| Suggesting | “You should try using X.” | “I noticed you value student collaboration. How might this tool support that goal?” |

| Reflecting | “Did the technology work?” | “What criteria did you use to evaluate the success of the lesson?” |

| Planning | “Next time, click here.” | “What would it look like if we automated that step?” |

6.3 Appreciative Inquiry (AI)

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is a change management approach that focuses on identifying and amplifying what is working rather than fixing what is broken. For resistant teachers, AI helps reconnect them with their core passion.

AI Interview Protocol for Tech Integration:

- Discovery: “Tell me about a specific time in your career when you felt most effective and engaged with your students.” (Grounds them in success).

- Dream: “Imagine that level of engagement was the norm. What was happening? What were students doing?”

- Design: “How could we use current tools to recreate those conditions more frequently? For example, if ‘student voice’ was the key, could a podcasting tool help amplify that?”.

Insight: AI bypasses the defensive “I’m not good at tech” response by focusing on “I am good at teaching.” The tech becomes merely the vehicle for the teaching success.

7. Practical Implementation: Strategies and Agendas

To move from theory to practice, schools need structured implementation plans.

7.1 The 30-Minute Coaching Cycle Agenda

Long, open-ended meetings are inefficient. A structured 30-minute agenda respects the teacher’s time and keeps the focus on implementation.

| Time | Phase | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| 00-05 | Connect & Praise | Validate a specific instructional strength observed previously. Build rapport. |

| 05-15 | One Small Step | Introduce one specific digital function that solves an immediate problem identified by the teacher. Avoid “feature dumping.” |

| 15-25 | Rehearsal | Crucial: The teacher takes the keyboard/mouse. They perform the task while the coach guides. “Muscle memory” is built here. |

| 25-30 | Plan & Backup | Decide when this will be used in class. Create an analog backup plan (e.g., “If the internet fails, we switch to handouts”). This reduces anxiety. |

7.2 The “Sandbox” Environment

Senior teachers often fear “breaking” the system or messing up live data (e.g., accidentally deleting grades).

- Strategy: Create “Sandbox” accounts—dummy courses populated with fake student data.

- Benefit: Teachers can click freely, make mistakes, and experiment without any real-world consequences. This psychological safety is essential for risk-averse learners.

7.3 Facilitating Small Peer Mentoring Sessions

Small group sessions (3-4 teachers) are often less intimidating than 1:1 coaching or large workshops.

- Structure: Group teachers by subject (e.g., “History Dept Tech Circle”).

- Activity: “Problem of Practice” Protocol.

- One teacher presents a non-tech problem (e.g., “Students aren’t doing the reading”).

- The group brainstorms solutions, including tech and non-tech options.

- The group selects one tech tool to pilot together.

- Role of Facilitator: To step back and let the peers teach each other, intervening only to correct technical misconceptions. This builds collective efficacy.

8. Case Studies of Success

8.1 Klein ISD: The Teacher-Leader Transformation

In Klein ISD (Texas), Ann, a long-time social studies teacher, transitioned to a district leadership role. Her success in driving digital transformation across 50 campuses was not rooted in her technical skill, but in her focus on relevance. She approached technology integration through the lens of “Life Lessons in Leadership,” connecting digital tools to the district’s core values. By empowering veteran teachers to lead the transformation, the district signaled that technology was a tool for teachers, not a replacement for them.

8.2 Freedom, Pennsylvania: The Reluctant Adopter

In rural Freedom, PA, a “once-hesitant” veteran teacher became a technology advocate. The turning point was not a mandate, but a realization of access. The teacher realized that digital tools allowed her to reach students who were geographically isolated or absent. The district supported her by providing “play” time—unstructured time to explore tools without the pressure of immediate implementation. This removed the “performance anxiety” and allowed her curiosity to take over.

8.3 DC Public Schools: LEAP Model

DC Public Schools implemented the LEAP (Learning together to Advance our Practice) model, which organizes teachers into content-specific teams led by a “LEAP Leader” (often a senior teacher). Technology training is integrated into these content cycles. Instead of a separate “Tech Tuesday,” tech is woven into the “Wednesday ELA Seminar.” This ensures that technology is never viewed as separate from instruction.

9. Recommendations for Educational Leaders

To systematically support senior teachers, leaders should implement the following action plan:

- Audit the “Why”: Ensure every technology initiative is explicitly linked to a pedagogical goal that senior teachers value (e.g., critical thinking, student equity). Use the Knoster Model to check for “Vision.”

- Formalize Reciprocal Mentoring: Launch a “Skill Swap” program. Provide clear guidelines and training for junior mentors to ensure respectful communication.

- Fund “Sandbox” & “Play” Time: Allocate paid time for teachers to explore tools in a risk-free environment (Sandbox accounts) without the pressure of immediate implementation.

- Establish a Safety Net: Create student help desks or rapid-response tech support so that “fear of failure” is minimized.

- Change the Metrics: Stop measuring “usage” (clicks/logins) and start measuring “impact” (pedagogical outcome). Involve senior teachers in defining these impact metrics.

- Reflect on Language: Conduct a “language audit” of PD materials. Remove deficit-based language and replace it with asset-based, andragogical terminology.

10. Conclusion

The resistance of senior teachers to technology is often a rational, principled response to a system that fails to value their established expertise. It is a symptom of a “Vision” or “Incentive” gap in the change management process. By shifting the organizational approach from “training” to “co-creation,” schools can bridge the generational divide.

The strategies outlined in this report—TPACK-based coaching, reverse mentoring, participatory design, and respectful facilitation—share a common core: Dignity. When senior teachers are approached with dignity, and when technology is presented as a servant to their pedagogy rather than a master of it, they become the most powerful agents of change in the school system. Their deep knowledge of teaching, combined with the efficiency of technology, creates the optimal environment for student learning. The goal is not to turn veteran teachers into “techies,” but to empower them to be what they have always been: master educators, now equipped with a modern toolkit.