Bridging Ed Tech Gaps: Teacher Prep for Digital Classrooms

The Digital Praxis Gap: Realigning Teacher Preparation with the Reality of the Connected Classroom

Executive Summary: The Myth of the Digital Native and the Reality of the Digital Divide

The contemporary educational landscape is characterized by a paradox: while K-12 classrooms have been rapidly transformed by the ubiquity of 1:1 computing, high-speed internet, and artificial intelligence, the preparation of the teachers destined to lead these classrooms remains tethered to 20th-century pedagogical models. A pervasive assumption exists among policymakers and the public that the current generation of teacher candidates—often labeled “digital natives”—possesses an innate fluency with technology that naturally translates into instructional capability. Empirical evidence and administrator feedback fundamentally dismantle this myth, revealing a profound “Digital Praxis Gap” where personal digital consumption fails to translate into professional digital pedagogy.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the current state of pre-service teacher (PST) preparation regarding classroom technology. By triangulating data from accreditation standards, course syllabi, principal surveys, and meta-analyses of educational technology efficacy, we identify systemic failures in how Teacher Education Programs (TEPs) prepare candidates for the “Digital Design Divide” identified in the 2024 National Education Technology Plan. The analysis moves beyond the superficial metrics of “computer literacy” to examine the deeper cognitive and logistical demands of the modern classroom—from the ethics of data privacy and the management of algorithmic bias to the physical orchestration of thirty devices in a 1:1 environment.

The findings suggest that without a radical restructuring of the teacher education curriculum—moving from “tool-centric” instruction to “adaptive digital expertise”—the profession risks perpetuating a system where technology serves as a distraction rather than a catalyst for learning. This report proposes a comprehensive realignment of theory and practice, advocating for an integrated, clinically-based approach to technology preparation that mirrors the complexity, friction, and potential of the real-world classroom.

Chapter I: The Standards Landscape and the “Digital Design Divide”

To understand the magnitude of the gap in teacher preparation, one must first establish the baseline expectations set by national policy and accreditation bodies. The divergence between the aspirational language of these standards and the operational reality of teacher preparation programs constitutes the first major barrier to effective technology integration. The 2024 National Education Technology Plan (NETP) fundamentally reframes the conversation, moving away from simple “access” to addressing the disparity in how technology is utilized to design learning.

1.1 The Evolution of Expectation: From Literacy to Design

Historically, teacher preparation standards focused on “computer literacy”—the ability to operate a machine, use a word processor, and navigate the internet. The current iteration of standards, specifically the ISTE Standards for Educators and the CAEP accreditation requirements, demands a far more sophisticated set of competencies that many programs fail to address adequately.

The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) Standards for Educators serve as the primary framework for digital pedagogy in the United States. They define the educator not merely as a user of technology, but as a “Learner, Leader, Citizen, Collaborator, Designer, Facilitator, and Analyst”. The “Designer” standard (2.5) is particularly critical, requiring educators to “design authentic, learner-driven activities and opportunities that use technology to accommodate learner variability”. This standard implies a deep integration of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles, yet syllabus reviews suggest that coursework often focuses on the mechanics of a tool rather than the design thinking required to use that tool to support diverse learners.

Similarly, the “Analyst” standard (2.7) expects educators to use technology to “provide alternative ways for students to demonstrate competency and reflect on their learning using technology”. This requires a fluency in learning analytics and alternative assessment strategies that is rarely found in introductory technology courses. The gap here is not just about knowing how to use an electronic gradebook, but understanding how to interpret the algorithmic feedback provided by adaptive learning platforms—a skill that combines data literacy with pedagogical insight.

1.2 The CAEP Accreditation Leverage and Its Limits

The Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP) serves as the gatekeeper for teacher preparation quality. CAEP Standard 1.5 explicitly requires providers to ensure that candidates model and apply technology standards. Theoretically, this should ensure that every accredited program produces tech-savvy teachers. However, the interpretation of “application” varies wildly across institutions, leading to inconsistent outcomes.

While CAEP requires “deep integration,” the structural reality in many Education Preparation Providers (EPPs) is the relegation of technology to a single, 3-credit “standalone” course. This structural decision, often driven by faculty capacity and credit-hour caps, creates a silo effect where technology is viewed as a separate subject rather than an ecological element of modern pedagogy. The accreditation process relies heavily on data reports and artifacts, which can often mask the lack of genuine integration. A candidate might pass an assessment by creating a lesson plan that includes technology (e.g., “Students will watch a YouTube video”), satisfying the letter of the standard while violating its spirit by using technology for passive consumption rather than active creation.

1.3 The National Education Technology Plan 2024: A New Mandate

The 2024 NETP introduces a critical taxonomy of the “Digital Divide,” moving beyond the simple “Access Divide” (who has devices) to the “Use Divide” and the “Design Divide”.

- The Digital Use Divide: This refers to the disparity in how students use technology—passive consumption vs. active creation.

- The Digital Design Divide: This is the most pertinent to teacher education. It highlights the inequity in the capacity of educators to design learning experiences that leverage technology for deep learning.

The NETP explicitly criticizes the “passive” use of technology and calls for “active” use, such as coding, media production, and digital problem-solving. Teacher preparation programs that focus solely on productivity tools (word processing, LMS management) are inadvertently contributing to the Design Divide by failing to equip teachers with the skills to facilitate creative digital work. If a teacher only knows how to use technology to display information, they cannot guide students to use technology to construct knowledge.

1.4 The State Policy Disconnect

While national standards set a high bar, state-level implementation often lags. For example, while Texas passed legislation requiring preservice teachers to be evaluated on their ability to teach in a digital environment (SB 1839), the implementation of such mandates often devolves into checklist compliance. State report cards under Title II of the Higher Education Act track “teacher training” in technology, but the data points are often binary (Did the program include tech training? Yes/No) and fail to capture the quality or depth of that training.

| Standard/Policy | Expectation for Pre-Service Teachers | Common Implementation Gap in TEPs |

|---|---|---|

| ISTE “Designer” | Use tech to design authentic, learner-driven activities. | Focus on “using” a tool (e.g., Kahoot) rather than “designing” with it. |

| ISTE “Citizen” | Model safe, legal, and ethical practices (data privacy). | Curriculum focuses on cyberbullying but ignores data privacy laws (FERPA). |

| CAEP Std. 1.5 | Deep integration of tech across the curriculum. | Tech is siloed in one course; methods courses remain analog. |

| NETP 2024 | Bridge the “Digital Design Divide” (active creation). | emphasis on “Digital Use” (consumption/productivity). |

| Title II Reporting | Report on tech preparation. | Data is binary and lacks qualitative assessment of proficiency. |

The disconnect is clear: we have 21st-century standards being met with 20th-century course structures. The result is a generation of teachers who are legally “qualified” but practically unprepared for the digital realities of the classroom.

Chapter II: Forensic Analysis of the Syllabus – What is Actually Taught

To understand why the “Digital Praxis Gap” persists, we must look beyond the high-level standards and examine the granular details of the curriculum. A forensic analysis of syllabi from various teacher education programs reveals the specific mechanisms of under-preparation. The primary tension lies between the “Standalone” model, which isolates technology, and the “Infused” model, which often dilutes it.

2.1 The Standalone Course: A Mile Wide and an Inch Deep

The vast majority of teacher preparation programs still utilize a single, standalone course (often titled “Introduction to Educational Technology” or “Technology in the Classroom”) to satisfy state and accreditation requirements. These courses are tasked with covering an impossibly broad spectrum of knowledge in a single semester, leading to superficial coverage of critical topics.

Analysis of typical syllabi reveals a “survey” approach. A single 15-week course might attempt to cover:

- History of Educational Technology

- Learning Theories (Behaviorism, Constructivism, Connectivism)

- Productivity Software (Microsoft Office, Google Workspace)

- Copyright and Fair Use

- 5.

Instructional Design Models (ADDIE, SAMR, TPACK)

- Specific EdTech Tools (LMS, Interactive Whiteboards, Assessment Apps)

- Digital Citizenship

The result is cognitive fragmentation. Candidates learn about these topics but rarely reach the level of application. For example, a syllabus might allocate one week to “Assessment Tools,” during which students are required to create a quiz in a specific platform like Kahoot or Google Forms. While this teaches the technical mechanics of the tool, it rarely allows time for the deeper pedagogical questions: Does this tool support valid assessment? How do I use the data exported from this tool to group students for remediation? What are the privacy implications of requiring students to create accounts on this platform?

Furthermore, the “Tool-Centric” nature of these syllabi ensures obsolescence. A course that spends three weeks teaching the specific functions of a SMART Board Model 600 is teaching a skill that will be useless if the candidate is hired by a district that uses Promethean panels or simple casting devices. The syllabus focuses on the noun (the tool) rather than the verb (the instructional action), leaving candidates ill-equipped to adapt when the hardware changes.

2.2 The Illusion of Integration: The Infused Model

In response to the limitations of the standalone course, some programs have moved to an “infused” model, where technology is integrated into content-area methods courses (e.g., Math Methods, Literacy Methods). While theoretically superior—as it situates technology within the context of the discipline—the reality is often less robust.

Research indicates that the success of the infused model is entirely dependent on the “technological self-efficacy” of the faculty members teaching the methods courses. A Literacy Professor who is an expert in phonics instruction but uncomfortable with digital tools may omit technology entirely or relegate it to a superficial add-on (e.g., “read a digital article”). Consequently, candidates may graduate with deep content knowledge but no understanding of the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) specific to their field.

2.3 The Missing Modules: Critical Omissions in Curricula

Comparing the syllabi data with the demands of the modern classroom reveals glaring omissions that contribute directly to the struggles of first-year teachers.

2.3.1 Technical Troubleshooting and “Digital First Aid”

New teachers are effectively the Tier 1 IT support for their classrooms. In a 1:1 environment, if a student cannot connect to the Wi-Fi or their audio is not working, learning stops. Yet, syllabi rarely include modules on technical troubleshooting.

- The Gap: Syllabi focus on “ideal state” usage—assuming hardware works perfectly.

- The Reality: The classroom is a “friction-heavy” environment. Teachers need to know the logic of troubleshooting: Is it the device? The network? The user? Without this training, minor technical glitches escalate into major classroom management disruptions.

2.3.2 Digital Classroom Management

Managing a classroom where every student has an open laptop is fundamentally different from managing a classroom of textbooks. Syllabi often treat “Classroom Management” and “Educational Technology” as separate domains, failing to address the intersection of the two.

- The Gap: Candidates are not taught specific routines for device management (e.g., “45-degree screens,” “Apple up,” “lids down”).

- The Reality: Novice teachers struggle to compete with the “distraction economy” of the internet. Without explicit training in monitoring software (like GoGuardian) or physical proximity control in a digital room, they often resort to banning devices entirely to maintain order.

2.3.3 Algorithmic Literacy and Data Interpretation

While “Data Driven Instruction” is a common buzzword in syllabi, the actual mechanics of interpreting data from digital platforms are often missing.

- The Gap: Candidates learn to input grades into a gradebook but are rarely taught to interpret the dashboards of adaptive learning systems (e.g., iReady, IXL, ALEKS).

- The Reality: Teachers are inundated with data visualizations they haven’t been trained to read. They may misinterpret “time on task” metrics or fail to intervene when an algorithm flags a student for remediation, simply because they don’t understand the backend logic of the tool.

2.4 Syllabus vs. Skills Comparison Table

The following table contrasts the typical verbs found in teacher education syllabi with the verbs required for survival in a modern classroom, highlighting the disconnect.

| Domain | Syllabus Verbs (Academic) | Classroom Verbs (Practical) | The Consequence of the Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware | “Identify,” “Describe,” “Utilize” | “Troubleshoot,” “Connect,” “Reset” | Teachers lose instructional time waiting for IT support for minor issues. |

| Software | “Create,” “Demonstrate,” “Present” | “Manage,” “Monitor,” “Integrate” | Teachers can make a slide deck but cannot manage the workflow of 30 students submitting them. |

| Data | “Collect,” “Analyze,” “Reflect” | “Interpret,” “Export,” “Secure” | Teachers view data as a compliance task rather than a formative tool. |

| Ethics | “Discuss,” “Define,” “Cite” | “Protect,” “Redact,” “Vet” | Teachers accidentally violate privacy laws by sharing student data on unvetted apps. |

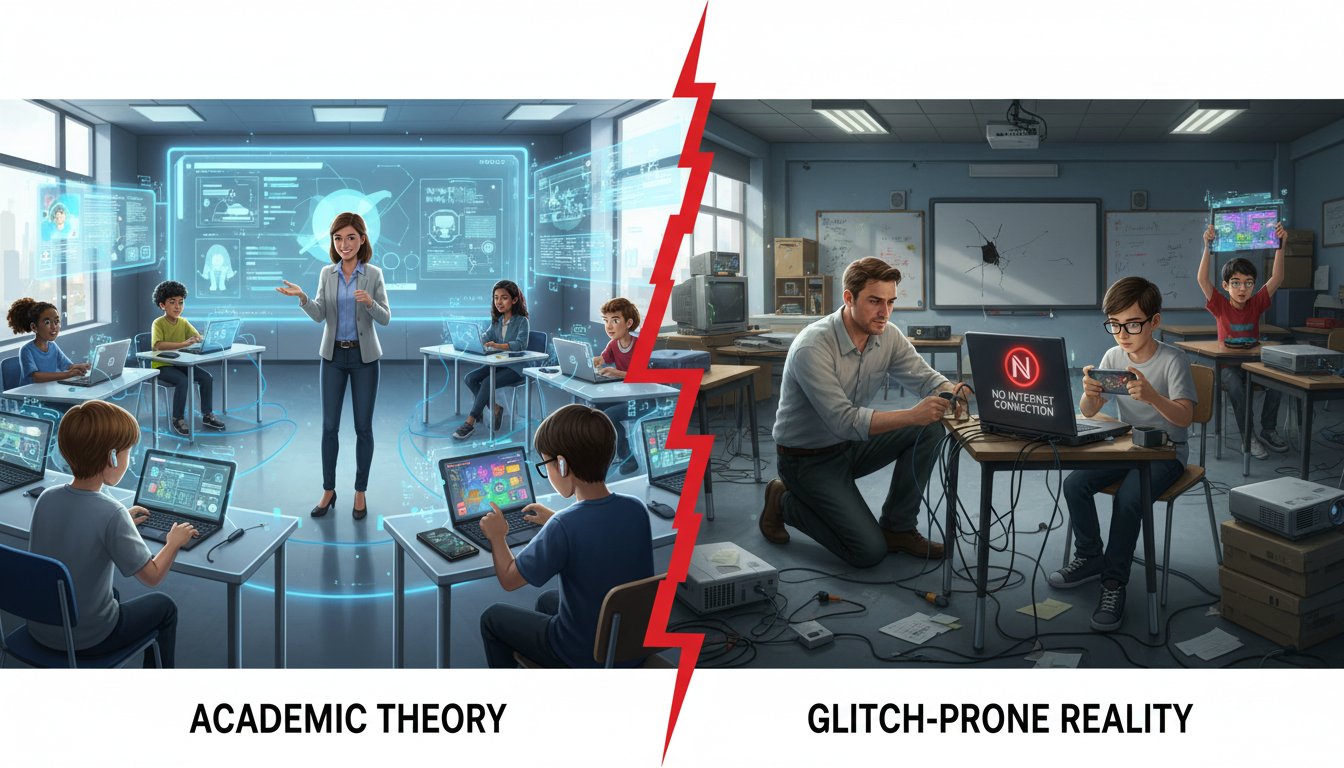

The forensic analysis suggests that current syllabi are preparing teachers for a “Best Case Scenario” classroom—one with perfect internet, working devices, and compliant students—rather than the complex, glitch-prone reality they will actually face.

Chapter III: Theory vs. Reality – The Friction of Deployment

The transition from the university lecture hall to the K-12 classroom exposes the “Theory-Practice Gap.” In the university setting, technology integration is often discussed through theoretical frameworks that assume a rational, controlled environment. In the K-12 classroom, technology integration is a messy, chaotic, and highly contextual negotiation. This chapter contrasts the dominant theoretical models taught in TEPs with the realities reported by first-year teachers and principals.

3.1 The TPACK Framework: Idealism vs. Cognitive Load

The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework is the dominant theoretical model used in teacher education to explain effective technology integration. It posits that effective teaching lies at the intersection of Content Knowledge (CK), Pedagogical Knowledge (PK), and Technological Knowledge (TK).

- Theory: In a university assignment, candidates have weeks to design a lesson where these three domains overlap perfectly. They might design a lesson where students use a specific app (TK) to explore a geometric concept (CK) using inquiry-based learning (PK). The lesson plan is graded on its theoretical soundness.

- Reality: In the classroom, the “Technological Knowledge” component is unstable. A teacher may have the perfect lesson plan, but if the app pushes an update that changes the interface five minutes before class, or if the school’s bandwidth throttles the connection, the “Tech” circle of the TPACK model collapses. Research on first-year teachers indicates that they are often overwhelmed by the logistics of technology distribution and login management, which consumes valuable instructional time.

- The Gap: Novice teachers lack “Technological Resilience.” Because their training emphasized the integration of the tool rather than the contingency planning for its failure, they often abandon the tech-enhanced lesson entirely when friction occurs, reverting to low-tech, teacher-centered methods to regain control.

3.2 The SAMR Model: Ladder vs. Lattice

The SAMR model (Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition) is another staple of teacher preparation, often presented as a ladder where “Redefinition” is the ultimate goal.

- Theory: Teachers are encouraged to constantly push towards “Redefinition”—using technology to do things that were previously inconceivable (e.g., collaborating with students in another country).

- Reality: In many high-stakes testing environments, “Substitution” (e.g., typing an essay instead of hand-writing it) and “Augmentation” (e.g., using spell-check) are the most practical and frequently used levels. The pressure to reach “Redefinition” can create anxiety for new teachers who feel they are failing if they aren’t orchestrating complex, transformative projects every day.

- The Gap: TEPs often fail to validate the utility of lower-level tech integration for efficiency and accessibility. By over-emphasizing “Redefinition,” they may inadvertently discourage teachers from using simple, effective tech strategies that streamline workflow but don’t necessarily “transform” the task.

3.3 The 1:1 Management Crisis: Theory Meets the “Distraction Economy”

Perhaps the most significant friction point is classroom management in a 1:1 environment.

- Theory: TEPs often teach classroom management through the lens of “engagement”—the idea that if a lesson is sufficiently engaging, behavioral issues will vanish.

- Reality: Even the most engaging lesson competes with the dopamine loops of social media, games, and YouTube, which are just a tab click away. Principals report that new teachers struggle profoundly with “monitoring” in a digital space. They lack the spatial awareness to position themselves to see screens (“monitoring from the back”) and the assertiveness to enforce “tech breaks”.

- The Consequence: This leads to the “Babysitter Effect,” where technology is used to pacify students rather than engage them.

New teachers, overwhelmed by the task of monitoring 30 screens, may assign “digital worksheets” simply to keep students quiet and seated, violating the active learning principles they were taught.

3.4 Principal Perspectives: The Hiring Disconnect

Surveys of school administrators reveal a specific set of frustrations regarding new teacher preparedness that TEPs rarely address.

- Adaptability Over Mastery: Principals prioritize the ability to learn new systems quickly over mastery of a specific legacy tool. They report that new teachers often lack the “digital resilience” to troubleshoot or pivot when technology fails. They want teachers who can say, “The server is down, so let’s switch to this analog backup,” rather than teachers who freeze.

- Professional Communication: A surprising gap exists in professional digital communication. Principals note that while new teachers are fluent in social media, they often lack the skills to compose professional emails to parents or manage the tone of digital communications within an LMS. The informality of text messaging often bleeds into professional correspondence, creating friction with parents and administration.

- Data Privacy Naivety: Principals are increasingly concerned about liability. They find that new teachers often sign up for “free” apps without vetting them for privacy compliance, exposing the district to legal risk. This “shadow IT” problem is a direct result of TEPs teaching candidates to be “innovators” without also teaching them to be “stewards” of data.

Chapter IV: The Invisible Curriculum – Data Privacy, Ethics, and Law

While “Digital Citizenship” is a standard component of most teacher preparation programs, it is often treated superficially, focusing on cyberbullying and netiquette. A critical examination of the current landscape reveals a dangerous gap in the legal and ethical preparation of teachers regarding student data privacy. This “Invisible Curriculum” is one of the most significant areas of liability for schools and districts.

4.1 The Legal Knowledge Gap: FERPA, COPPA, and CIPA

Federal laws such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), and the Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA) govern the digital lives of students. However, syllabus reviews indicate that these legal frameworks are rarely taught in depth.

- The “Click-Wrap” Trap: Novice teachers, eager to find engaging tools, often fall into the “Click-Wrap” trap—clicking “I Agree” on the Terms of Service for a free educational app without reading the fine print. They may unknowingly grant a third-party vendor the right to sell student data, track location, or market to children.

- The Roster Upload: A common error among unprepared teachers is uploading a class roster (containing full names and IDs) to a non-district-approved website to generate student accounts. This constitutes a direct violation of FERPA. TEPs often fail to simulate this scenario, leaving teachers to learn through trial and (potentially catastrophic) error.

4.2 The “Sharenting” Dilemma and Social Media Professionalism

The boundary between a teacher’s personal digital life and their professional obligations is increasingly blurred.

- Social Media Ethics: While candidates are often warned to “clean up” their own social media profiles for the job market, they are less frequently trained on the ethics of posting about their students. The phenomenon of “teacher influencers”—educators who monetize their classroom experiences on TikTok or Instagram—sends mixed messages. New teachers need explicit guidance on the rights of students not to be content for a teacher’s social media brand.

- Scenario-Based Training: Effective preparation requires more than a lecture on “professionalism.” It requires scenario-based training: What do you do if a student sends you a friend request? What do you do if a parent attacks you on a community Facebook page? How do you handle a student disclosing self-harm in a digital journal entry? These “grey area” scenarios are where novice teachers often stumble.

4.3 Data Stewardship vs. Data Entry

Teacher preparation often conflates “using data” with “entering data.”

- Data Stewardship: Teachers are the stewards of sensitive student information. They need to understand the lifecycle of data: where it is stored, who has access to it, and when it should be deleted.

- The Security Mindset: Basic cybersecurity hygiene—password management, recognizing phishing attempts, and securing devices—is a critical competency. With K-12 districts becoming prime targets for ransomware attacks, every teacher is a potential entry point for a breach. TEPs must view cybersecurity training not as an IT concern, but as a pedagogical necessity.

Chapter V: The Artificial Intelligence Disruption – The New Frontier

The emergence of Generative AI (GenAI) represents the single largest disruption to education in decades, outpacing the revision cycles of university curricula. The 2024 educational landscape is one where students often possess greater AI fluency than their teachers, creating a dangerous inversion of expertise.

5.1 The AI Literacy Vacuum

Current data indicates a “moderate” to “low” level of AI competency among pre-service teachers, particularly in the domains of AI ethics, problem-solving, and pedagogical application.

- Reactive vs. Proactive: Most Higher Education institutions have reacted to AI primarily as a threat to academic integrity (plagiarism), rather than as a transformative tool. Consequently, pre-service teachers are often trained on detecting AI use rather than leveraging it.

- Syllabus Lag: University course approval processes can take 12-24 months. Generative AI evolves weekly. This bureaucratic lag means most official syllabi do not yet account for tools like ChatGPT, MagicSchool.ai, or Microsoft Copilot, leaving graduates to enter 2025 classrooms with 2020 skill sets.

5.2 Defining AI Competencies for New Teachers

To bridge this gap, Teacher Preparation Programs must adopt a specific AI Competency Framework. Research identifies three critical dimensions:

- AI Pedagogy (Teaching with AI):

- Differentiation: Using AI to instantly level reading passages, generate bilingual resources, or create Universal Design for Learning (UDL) supports.

- Administrative Efficiency: Using AI to automate routine tasks (lesson planning, email drafting, rubric generation) to reduce burnout.

- Tutor Integration: Learning to orchestrate classrooms where students interact with AI tutors (e.g., Khanmigo) while the teacher acts as a facilitator.

- AI Literacy (Teaching about AI):

- Mechanism: Understanding the basics of how Large Language Models (LLMs) function (e.g., probabilistic token prediction) to dispel the myth that AI is “thinking” or “knowing.”

- Hallucination & Verification: Training teachers to verify AI outputs. A teacher who cannot spot an AI hallucination cannot teach students to do so.

- AI Ethics (The Human in the Loop):

- Bias: Understanding that AI models are trained on biased datasets and will reproduce societal prejudices. Teachers must be the “human in the loop” to vet content for cultural bias before it reaches students.

- Intellectual Property: Navigating the complex copyright issues surrounding AI-generated content.

5.3 The Risk of the “Black Box”

Without explicit training, new teachers risk treating AI as a “Black Box” of truth. This is particularly dangerous in assessment. If a teacher relies on an AI grading tool without understanding its criteria, they abdicate their professional judgment. TEPs must emphasize that AI is a “co-pilot,” not an “autopilot”.

Chapter VI: Systemic Barriers to Reform

Why do these gaps persist despite decades of calls for “technology integration”? The barriers are systemic, structural, and cultural within the Higher Education institutions themselves.

6.1 Faculty Capacity and the “Second-Order” Barrier

The “Digital Design Divide” applies as much to the faculty of teacher education programs as it does to K-12 students.

- The Generational Gap: Many tenured faculty members have not taught in a K-12 classroom for decades—long before the advent of the iPad or the Chromebook. If methods professors do not model technology use, pre-service teachers view it as optional. Research shows that faculty modeling is the single strongest predictor of whether candidates will use technology themselves.

- Professional Development Gap: University faculty often lack the incentives to update their tech skills. Tenure and promotion structures prioritize research publication over the time-consuming work of redesigning courses to include rapidly changing technologies.

6.2 The Silo Effect and Interdisciplinary Failure

Universities are notoriously compartmentalized. The Computer Science department (which possesses the expertise on AI and coding) rarely collaborates with the School of Education. This prevents the cross-pollination of ideas that could result in robust “Computational Thinking” modules for future teachers. Teacher candidates are left to learn “tech” from education generalists rather than technology specialists.

6.3 Accreditation as a Floor, Not a Ceiling

While accreditation bodies like CAEP mandate technology integration, the evidence required is often bureaucratic rather than pedagogical.

A program can demonstrate compliance by showing that a “technology course” exists, without necessarily proving that the course effectively prepares candidates for the classroom reality. The Title II reporting system, which is supposed to provide accountability, offers little meaningful data on technology preparedness, allowing low-performing programs to fly under the radar.

Chapter VII: The Path Forward – Recommendations for Curriculum Improvement

To address these systemic gaps, Teacher Education Programs must undertake a radical restructuring of their approach to educational technology. The following proposals are based on the synthesis of “High-Leverage Practices” and successful innovations in the field.

7.1 Structural Reform: The “Sandwich” Model

The debate between “Standalone” and “Infused” models should be resolved by adopting a “Sandwich” approach:

- Year 1 Foundation (The Bottom Bun): A “Digital Fluency & Ethics” course. This course focuses on the “hard skills” of troubleshooting, LMS management, and the legal/ethical frameworks (FERPA, AI ethics). It lays the technical groundwork.

- Years 2-3 Integration (The Meat): Methods courses (Math, Science, Literacy) must include specific technology assignments.

- Math Methods: Must include modules on dynamic geometry software (Desmos, GeoGebra).

- Literacy Methods: Must include digital storytelling, e-readers, and AI writing assistants.

- Mechanism: This requires co-teaching or heavy collaboration between EdTech specialists and Methods faculty.

- Year 4 Capstone (The Top Bun): A “Digital Pedagogy & Innovation” seminar taken during student teaching. This course acts as a “just-in-time” support, helping candidates apply their skills to the specific context of their placement school (e.g., “My school uses Canvas; help me optimize it”).

7.2 The “Digital Clinical Experience”

Clinical practice (student teaching) is where theory meets reality. It must be explicitly re-engineered to support digital growth.

- Tech-Mentor Matching: Placements should prioritize cooperating teachers who are modeled “Digital Leaders.” Placing a tech-savvy student teacher with a tech-phobic mentor often leads to the candidate regressing to traditional methods.

- The “Tech Audit” Assignment: Instead of just observing, pre-service teachers should conduct a “Technology Ecosystem Audit” of their placement school—identifying the LMS, the hardware constraints, the privacy policies, and the support workflow. This builds the “Analyst” capability.

- Virtual Placements: TEPs should explore partnerships with virtual schools to offer clinical placements in online or hybrid environments, ensuring candidates are prepared for the possibility of remote instruction.

7.3 New Mandatory Modules

Curricula must add explicit, assessed modules on “The Invisible Tech”:

- Tier 1 Troubleshooting Certification: A “Digital First Aid” badge covering connectivity, projection, and basic hardware fixes. This builds the “Digital Resilience” principals crave.

- Data Governance Simulation: A case-study-based module where students must identify privacy violations in realistic school scenarios.

- AI Prompt Engineering: A workshop on crafting effective prompts for educational AI tools, focusing on differentiation and assessment design.

7.4 Assessing “Digital Resilience”

Finally, assessment in TEPs must move away from static artifacts (e.g., “Make a PowerPoint”) to dynamic scenarios.

- Simulation Assessments: Present candidates with a “tech failure” scenario: “The internet is down, your slide deck is inaccessible, and you have 25 students with iPads. How do you pivot?” This assesses adaptability.

- Portfolio of Practice: Require a digital portfolio that demonstrates the evolution of a lesson through technology, including student work samples and reflection on what failed, rather than just the final lesson plan.

Chapter VIII: Conclusion

The preparation of pre-service teachers regarding classroom technology is currently functioning on an outdated operating system. It presupposes that “digital nativism” equates to pedagogical expertise and that technology is a separate tool rather than the environment in which modern learning occurs.

The data suggests that the “gaps” are not merely holes in knowledge, but structural flaws in how teaching is conceptualized in the 21st century. The focus must shift from Technological Literacy (knowing how to use the tool) to Technological Fluency (knowing when and why to use the tool) and finally to Adaptive Digital Expertise (knowing how to design, troubleshoot, and pivot in a complex digital ecosystem).

For Teacher Education Programs, the path forward requires breaking down the silos between content and code, prioritizing the “unsexy” skills of data privacy and management, and engaging directly with the AI disruption. Only by aligning the curriculum with the chaotic, connected reality of the modern classroom can we ensure that new teachers are not just surviving their first year, but leading the next generation of digital learners.

Appendix: Comparative Data Tables

Table A1: The Curriculum Gap – Syllabus vs. Reality

| Domain | What Syllabi Typically Cover | What Classrooms Actually Require | The “Praxis Gap” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware | Idealized use of SmartBoards, iPads. | Troubleshooting connectivity, audio issues, legacy hardware. | Teachers lose instruction time waiting for IT; technology is abandoned. |

| Software | Creating content (Slides, Prezi). | Managing workflow (LMS, Google Classroom), Interoperability. | Teachers create content but cannot manage the digital collection/grading. |

| Classroom Mgmt | Cyberbullying, Netiquette. | Monitoring software (GoGuardian), “Screens Down” routines, Distraction mgmt. | “The Babysitter Effect” – Tech used to pacify rather than engage. |

| Data | Gradebook entry. | Interpreting adaptive learning dashboards, formative analytics. | Data is used for compliance, not instruction. |

| Law/Ethics | Copyright, Plagiarism. | FERPA, COPPA, Data Privacy, AI Ethics, “Sharenting.” | Legal liability for districts; privacy violations. |

Table A2: Evolution of Required Competencies

| Competency Domain | 2015 Requirement (Legacy) | 2025 Requirement (Modern) |

|---|---|---|

| Search | Boolean operators, Google Search. | Prompt engineering, AI hallucination verification. |

| Creation | Word processing, basic video. | Multimedia production, coding/computational thinking. |

| Assessment | Online quizzes (Kahoot). | AI-resilient assessment design, process-based evaluation. |

| Collaboration | Google Docs shared editing. | Global collaboration, project management in digital teams. |

| Security | Password protection. | Phishing awareness, data lifecycle management, 2FA. |

Table A3: Stakeholder Needs Analysis

| Stakeholder | Needs/Frustrations | Source Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Principals | Want “Digital Resilience,” adaptability, and professional communication skills. | |

| New Teachers | Feel overwhelmed by logistics (logins, devices); lack confidence in teaching with tech. | |

| Students | Need “Active Use” (Design) rather than passive consumption; need guidance on AI ethics. | |

| Faculty (TEP) | Struggle to keep up with rapid tech changes; lack incentives for curriculum redesign. |