EdTech Minimalism: Low-Tech, High-Impact Classroom Tools

The Pedagogy of Minimalism: Optimizing Classroom Instruction Through Low-Tech, High-Impact Digital Tools

1. Introduction: The Imperative for EdTech Minimalism

The contemporary educational landscape is currently navigating a paradox of abundance. In the wake of the global COVID-19 pandemic, schools underwent a rapid, often chaotic digitalization, transitioning from environments of scarce technology to a saturation of devices and software. Prior to 2020, the primary challenge in educational technology (EdTech) was access; however, following the unprecedented procurement of devices that propelled many districts to a 1:1 student-to-device ratio, the challenge has shifted to selection and sustainability. Teachers, once starved for digital resources, are now inundated with them. A 2024 report indicates that the number of EdTech tools utilized by school districts has tripled since 2018, ballooning from an average of 841 tools to over 2,700 distinct applications.

This explosion of digital options has not correlated linearly with improved student outcomes or reduced teacher workload. Instead, it has often resulted in “tool fatigue,” fragmented attention, and a cognitive burden that distracts from the core enterprise of teaching and learning. The prevailing narrative in educational reform often champions artificial intelligence (AI) and complex adaptive platforms as the future of instruction. However, this report posits a counter-narrative: the most high-impact technologies for the average classroom are not the newest or the most advanced, but the most accessible and reliable.

The philosophy of “EdTech Minimalism,” as articulated by researchers and practitioners like Paul Emerich France, argues for a reduction in digital reliance to foster more intentional, connected, and human-centric classroom experiences. Minimalism is not a rejection of technology; rather, it is a rigorous pedagogical framework that prioritizes tools that minimize logistical complexity while maximizing student agency and human connection. The goal is to identify “Low-Tech” solutions—ubiquitous, stable, and user-friendly platforms like Google Workspace and simple polling apps—that yield “High-Impact” results in learning mastery and workload reduction.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of four such technologies: Google Forms, Google Slides (used as interactive notebooks), Learning Management System (LMS) feedback tools, and Plickers. By leveraging features often overlooked—such as branching logic, response validation, audio feedback, and virtual manipulatives—educators can achieve sophisticated differentiation and immediate feedback loops that rival expensive AI solutions. Furthermore, this report outlines a methodology for “Teacher Action Research,” empowering educators to document the efficacy of these tools through rigorous before-and-after analysis, ensuring that pedagogical decisions are driven by data rather than hype.

1.1 The Theoretical Basis: Cognitive Load and Usability

The argument for low-tech solutions is grounded in the cognitive science of learning. Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) posits that the human brain has a limited capacity for processing novel information in working memory. When instructional design is cluttered with extraneous elements—complex navigation menus, unnecessary gamification, or unstable interfaces—it imposes “extraneous cognitive load.” This mental effort competes with the “germane cognitive load” required to process the actual subject matter, thereby inhibiting learning.

Advanced EdTech tools often violate the principles of multimedia learning established by Richard Mayer, particularly the Coherence Principle, which states that people learn better when extraneous words, pictures, and sounds are excluded. High-tech platforms often rely on “bells and whistles” to engage students, but these features can distract from the learning objective. In contrast, minimalist tools like a stark Google Form or a simple slide deck naturally adhere to the Signalling Principle (highlighting essential material) and the Spatial Contiguity Principle (aligning text with relevant graphics) simply because they lack the capacity for sensory overload.

Furthermore, the “usability” of a tool is a critical factor in teacher workload reduction. A tool that requires significant time to set up, troubleshoot, or grade violates the minimalist principle of efficiency. As the subsequent sections will demonstrate, the transition to low-tech automation—such as self-grading forms and audio feedback—can reduce grading time by significant margins, directly addressing the crisis of teacher burnout.

2. Google Forms: The Engine of Adaptive Mastery

2.1 Mastery Paths and Branching Logic

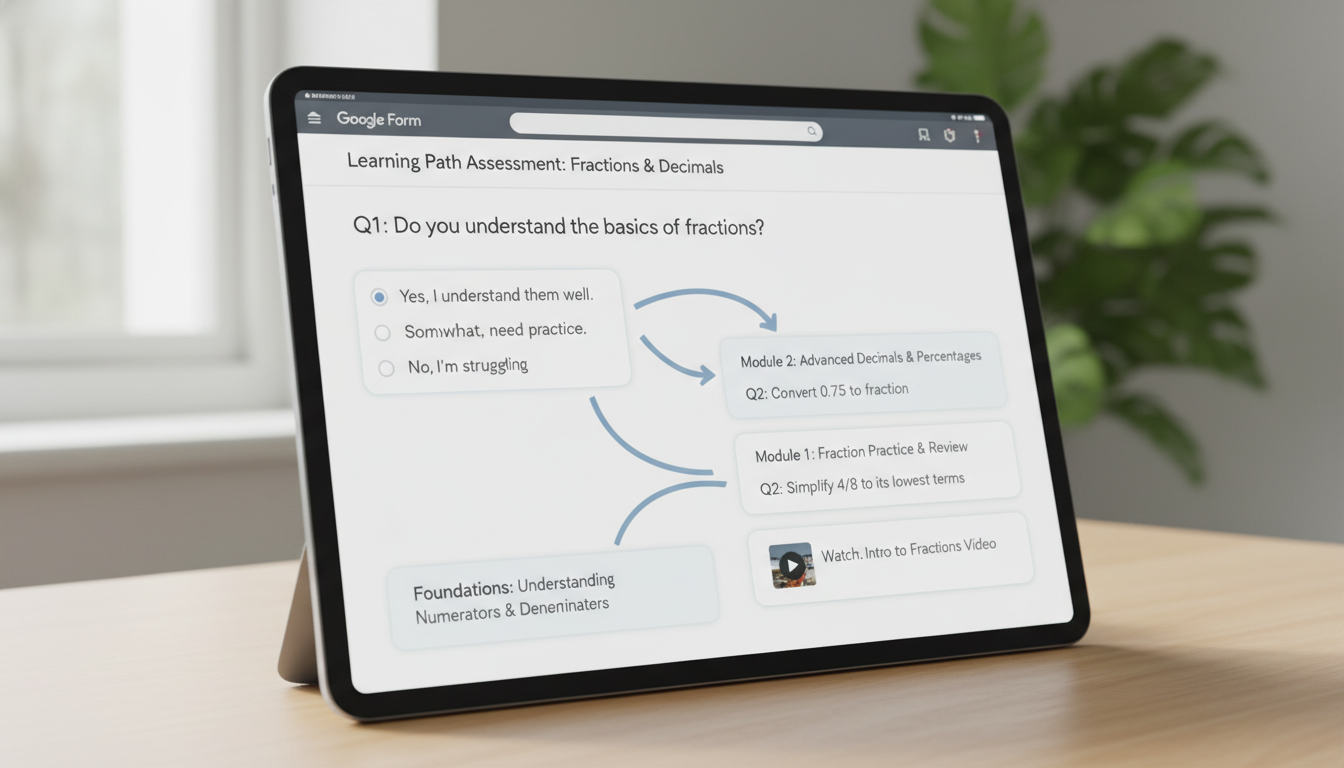

One of the most significant challenges in the modern classroom is differentiation—the requirement to tailor instruction to the diverse needs of learners. Traditional methods of differentiation, such as creating multiple versions of a worksheet, are time-consuming and often socially stigmatizing for students who receive the “easier” work. Google Forms resolves this dilemma through “Branching Logic,” specifically the “Go to section based on answer” feature.

2.1.1 The Architecture of a Branching Form

The branching form operates on a “diagnosis and route” mechanism. The teacher designs a form divided into distinct “Sections.” The first section serves as a diagnostic checkpoint. Based on the student’s selection in a multiple-choice question, the form automatically directs them to a specific subsequent section.

- The Remediation Path: If a student selects an incorrect answer (e.g., Option B), the form directs them to a “Remediation Section.” This section does not simply repeat the question; it embeds a micro-instructional intervention. This could be a short YouTube video explaining the concept, a diagram, or a brief reading passage. Following this intervention, the student is presented with a “Check for Understanding” question to verify mastery before being routed back to the main assessment path.

- The Enrichment Path: If a student selects the correct answer, they are directed to an “Enrichment Section” or simply allowed to proceed to the next conceptual tier. This ensures that advanced learners are not held back by remediation they do not need.

This structure mimics the adaptive algorithms of expensive platforms like ALEKS or DreamBox but retains the teacher’s agency. The teacher, not an opaque algorithm, decides exactly what remediation material is presented. This creates a “Mastery Loop,” ensuring that students cannot proceed to complex synthesis tasks without demonstrating foundational understanding.

2.1.2 Case Study: The “Choose Your Path” Lesson

Research into the application of branching forms in social studies classrooms illustrates their potential for student agency. In a “Choose Your Path” lesson regarding the U.S. Constitution, students were presented with a non-linear narrative where they could choose which branch of government to explore. However, the form enforced accountability; if a student failed to answer a comprehension question regarding the Legislative Branch correctly, the “branching” logic forced a review of the material.

This approach transforms the assessment from a summative judgment (a grade) into a formative learning experience. The “failure” to answer correctly triggers support rather than punishment. Teachers implementing this method report that it allows for “asynchronous personalization,” freeing the teacher to circulate and work one-on-one with struggling students while the Form manages the pacing for the rest of the class.

2.2 Immediate Feedback via Response Validation

While branching handles the macro-flow of the lesson, “Response Validation” manages the micro-interactions. This feature, available for “Short Answer” questions, allows the teacher to set specific criteria that a student’s answer must meet before the form will accept it.

2.2.1 The “Hard Stop” Intervention

In a traditional paper worksheet, a student might complete ten problems incorrectly and not realize their error until the paper is returned days later. Educational research emphasizes that feedback is most effective when it is immediate. Response validation creates a “Hard Stop“: if the student enters an incorrect answer, the form prevents submission and displays a custom error message.

The pedagogical power lies in the custom error message. Instead of a generic “Invalid Input,” the teacher can program a specific hint. For example, in a science calculation, the error message might read: “Incorrect. Did you remember to convert mass to kilograms first?” This forces the student to re-evaluate their work in the moment of cognitive engagement, rather than days later.

2.2.2 Regular Expressions (RegEx) for Precision and Literacy

For advanced validation, teachers can utilize Regular Expressions (RegEx). This “low-tech” coding feature allows for sophisticated pattern matching that promotes disciplinary literacy.

- Literacy and Syntax: A teacher can use RegEx to ensure that a student’s response contains specific vocabulary or formatting. For example, a validation rule could require that a response includes the words “photosynthesis” and “energy.” If the student attempts to submit a vague answer like “The plant makes food,” the form effectively says, “Your answer is too simple. Please use the correct scientific terminology”.

- Flexibility: RegEx also solves the “typo” frustration of auto-grading.

A pattern such as (?i)^(gray|grey)$ instructs the form to accept “gray” OR “grey,” and to ignore capitalization (case-insensitive). This prevents the demoralizing experience of being marked wrong for a correct but alternatively spelled answer, a common complaint with rigid digital tools.

| Validation Type | Function | Pedagogical Application | Custom Error Message Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text (Contains) | Checks for a specific substring. | Ensuring students use required vocabulary in a definition. | “Your definition must include the word ‘mitochondria’.” |

| Number (Between) | Checks if input is within a range. | Estimation tasks in math or science labs. | “Your estimate is too far off. Look at the graph scale again.” |

| Length (Minimum Count) | Enforces a minimum character count. | Preventing one-word answers in writing prompts; forcing elaboration. | “Please explain your reasoning in at least 50 characters.” |

| Regular Expression (Matches) | Checks against a complex pattern. | Verifying chemical equations, dates, or accepting multiple spellings. | “Please format the date as DD-MM-YYYY.” |

The Digital Escape Room: Gamification Without the Grief

A popular and high-impact application of validation and branching is the “Digital Escape Room.” In this model, the “locks” of a physical escape room are replaced by “Sections” in a Google Form. To move to the next section, students must enter a code derived from solving content-based puzzles.

Impact on Collaboration and Engagement

The digital escape room leverages the principles of gamification—challenge, narrative, and immediate feedback—without requiring complex accounts or video game engines.

- Collaborative Friction: When used in small groups, the single device (usually a Chromebook) becomes a focal point for discussion. Because the form acts as the impartial judge of correctness, students debate the content with each other to find the solution. “Why is the code 452? I thought the answer to number 3 was 7.” This generates rich peer-to-peer instruction.

- Data Integrity: Unlike physical locks, which can be picked or broken, digital validation is absolute. Teachers receive timestamped data indicating exactly when a group “escaped” or which puzzle caused a bottleneck, providing valuable formative assessment data.

Workload Reduction: The Auto-Grading Paradigm

The shift from manual grading to auto-graded Forms offers perhaps the most quantifiable return on investment regarding teacher time.

- Time Audit: Teachers report that auto-grading quizzes saves hours of work per week. For a secondary teacher with 150 students, replacing one manual quiz per week with an auto-graded Form saves approximately 3-5 hours of grading time. This is not merely a convenience; it is a sustainability strategy.

- Analytics vs. Scoring: The true value is not just the grade, but the item analysis. Google Forms generates a summary view showing the percentage of students who missed each question. This enables “Just-in-Time Teaching” (JiTT). A teacher can review the data five minutes before class, see that 60% of students missed Question 4, and adjust the lesson plan to focus specifically on that misconception.

Google Slides: The Interactive Canvas

While Google Slides is traditionally viewed as a presentation tool—a digital successor to the overhead projector—its most potent classroom application is as a platform for Digital Interactive Notebooks (DINBs) and Virtual Manipulatives. This shifts the tool from a “teacher-broadcast” medium to a “student-creation” workspace.

The Digital Interactive Notebook (DINB)

A DINB is a slide deck where students document their learning, organizing notes, reflections, and activities in a single cloud-based file. Unlike a physical notebook, the DINB is multimodal, allowing students to integrate text, images, video, and hyperlinks.

Documenting Before-and-After Learning Improvements

The impact of Interactive Notebooks (both physical and digital) on student achievement has been the subject of quantitative action research. A notable study conducted at “South High School” (pseudonym) investigated the effect of interactive notebooks on Algebra achievement. The study utilized a pre-test/post-test design and found that the implementation of the notebook strategy significantly improved standardized test scores.

- The Mechanism of Improvement: The study suggests that the notebook serves as a “problem space” for inquiry. By organizing information via the “SOAR” strategies (Selection, Organization, Association, and Regulation), students actively process content rather than passively recording it.

- Action Research Data: In similar studies involving biology students, the use of interactive notebooks was correlated with higher proficiency on subject area testing programs. Teachers documenting “before-and-after” improvements can use the DINB as a portfolio of growth. A “Before” slide might show a student’s initial, misconceptions-laden explanation of a concept, while an “After” slide later in the deck demonstrates a revised, accurate explanation, providing tangible evidence of learning.

Comparison to Physical Notebooks

While physical notebooks have tactile benefits, DINBs offer distinct advantages for “deepening knowledge”:

- Multimodality: Dual Coding Theory suggests that combining text with images enhances memory. In a DINB, a student can insert a photograph of a lab experiment, label it with digital arrows, and link to a video explanation. This synthesis is logistically difficult on paper.

- Permanence: A major barrier for disorganized students is the “lost notebook.” The DINB is searchable, cloud-saved, and accessible from any device, preserving the “external memory” of the student.

Virtual Manipulatives: Efficiency and Equity

Virtual manipulatives (VMs)—movable digital objects like base-ten blocks, fraction bars, or chemical atoms—can be easily created in Google Slides. By setting a background image (the “game board”) and placing movable shapes on top, teachers create “drag-and-drop” learning environments.

Virtual vs. Concrete: The Efficacy Debate

There is a longstanding pedagogical debate regarding physical versus virtual manipulatives. A meta-analysis by Moyer-Packenham et al. challenges the assumption that “physical is always better,” finding that VMs are at least as effective, and often more effective, for specific concepts.

- The “Impossible Error” Factor: Physical manipulatives can be misused; a student might cut a paper fraction strip unevenly, leading to a false conclusion about equivalence. Virtual manipulatives are mathematically perfect. A digital “1/3” block is exactly one-third the length of a “1” block. This precision prevents misconceptions caused by physical error.

- Efficiency: VMs allow for rapid reset and repetition. A student can drag blocks to solve a problem, hit “Undo” to reset, and try again in seconds. This efficiency increases the volume of practice possible in a class period.

- Equity and Access: During the shift to virtual instruction, the lack of physical manipulatives at home was a major barrier. Google Slides democratized access to these cognitive tools, ensuring that students in under-resourced environments could still engage in concrete-representational-abstract (CRA) learning.

Case Study: Fraction Operations

A quasi-experimental study examining the use of virtual manipulatives for fifth-grade fraction addition found significant benefits. While both the control group (concrete manipulatives) and the experimental group (virtual manipulatives) improved, the VM group reported higher engagement and conceptual understanding. The ability to layer semi-transparent fraction bars in Slides allowed students to “see through” the shapes to verify equivalence, a visual scaffold impossible with opaque plastic tiles.

Collaborative Learning in Slides

Google Slides also facilitates synchronous collaboration through “Whole-Class” slide decks. In this workflow, every student is assigned one slide in a shared presentation.

- The Digital Panopticon: The teacher can switch to “Grid View” and observe 30 students working simultaneously in real-time. This provides immediate insight into student progress. If a student is off-track, the teacher can type a corrective comment directly onto their slide instantly.

- Social Construction of Knowledge: Students can view their peers’ slides to see alternative problem-solving strategies. This transparency fosters a culture where learning is public and communal rather than private and isolated.

The Feedback Loop: LMS Comments and Audio

In the Learning Management System (LMS) environment—whether Google Classroom, Canvas, or others—the “Comments” feature is the primary channel for teacher-student dialogue. However, providing high-quality written feedback is one of the most time-consuming tasks in education, often contributing to the “impossible workload” that drives burnout. This section analyzes two low-tech methodologies that dramatically improve feedback quality while reducing time: Comment Banks and Audio Feedback.

The Efficiency of Comment Banks

A “Comment Bank” is a repository of pre-written, high-quality feedback statements that can be inserted into student work with a click or a shortcut code.

Reducing Repetitive Strain

Pareto’s Principle applies to grading: approximately 80% of student errors stem from 20% of the concepts. Teachers often find themselves typing “Cite your evidence” or “Check your significant figures” hundreds of times per assignment.

- Technical Implementation: Google Classroom has a native Comment Bank feature.

Teachers can store detailed explanations, complete with hyperlinks to resources (e.g., a link to a video tutorial on how to cite evidence).

- Workflow Integration: By typing a hashtag (#) followed by a keyword (e.g., #cite), the system suggests the pre-written comment. This allows the teacher to insert a paragraph-long, resource-rich explanation in seconds.

- Pedagogical Value: This ensures that even “quick” grading provides rich instructional value. Instead of a terse “Wrong,” the student receives a detailed explanation of the error and a path to correction, standardized across the class.

4.2 Audio Feedback: The Power of Voice

Audio feedback involves recording a spoken commentary on student work rather than typing text. Tools like Mote (integrated into Google Forms/Slides) or native LMS recording features facilitate this.

4.2.1 Speed and Information Density

Research consistently demonstrates that humans speak much faster than they type. A study by Lunt and Curran found that one minute of audio feedback is equivalent to six minutes of writing time in terms of content generation.

- The Time Audit: A 3-minute audio clip can convey over 400 words of nuanced critique. Typing 400 words of feedback per student for 100 students is logistically impossible within a standard workweek; speaking it is manageable.

- Nuance and Tone: Written feedback is often devoid of tone, leading students to misinterpret constructive criticism as harsh or punitive. Audio allows the teacher to use intonation to convey encouragement, softening the delivery of critique. Studies show that students perceive audio feedback as more “personal,” “caring,” and “supportive” than text.

4.2.2 Student Engagement and Retention

A pervasive issue in education is “unread feedback,” where students look at the grade and ignore the comments. However, research indicates a strong student preference for audio.

- Accessibility: For students with reading disabilities or lower literacy levels, audio feedback bypasses the decoding barrier, allowing them to focus entirely on the content of the feedback.

- Preference: In focus groups, students reported that audio feedback was “clearer” and easier to understand, particularly for global issues like essay structure and argumentation. Written feedback was preferred only for specific grammatical corrections.

| Feedback Modality | Avg. Time Per Student (Essay) | Total Time (100 Students) | Quality of Nuance | Student Perception |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual (Pen/Paper) | 10-12 minutes | ~18 hours | High nuance, but often illegible. | Impersonal; “Red Ink” anxiety. |

| Typing (No Bank) | 8-10 minutes | ~14 hours | Legible, but repetitive. Tone often flat. | Transactional. |

| Comment Bank | 4-5 minutes | ~7.5 hours | Standardized, resource-rich. | Helpful, but generic. |

| Audio Feedback | 2-3 minutes | ~4 hours | Highly nuanced, personal tone. | Personal, supportive, detailed. |

Insight: The transition from manual grading to audio feedback effectively “buys back” a teacher’s weekend. It is arguably the single most effective low-tech intervention for teacher retention and sustainability.

5. Plickers: The “Smartphone-Free” Digital Classroom

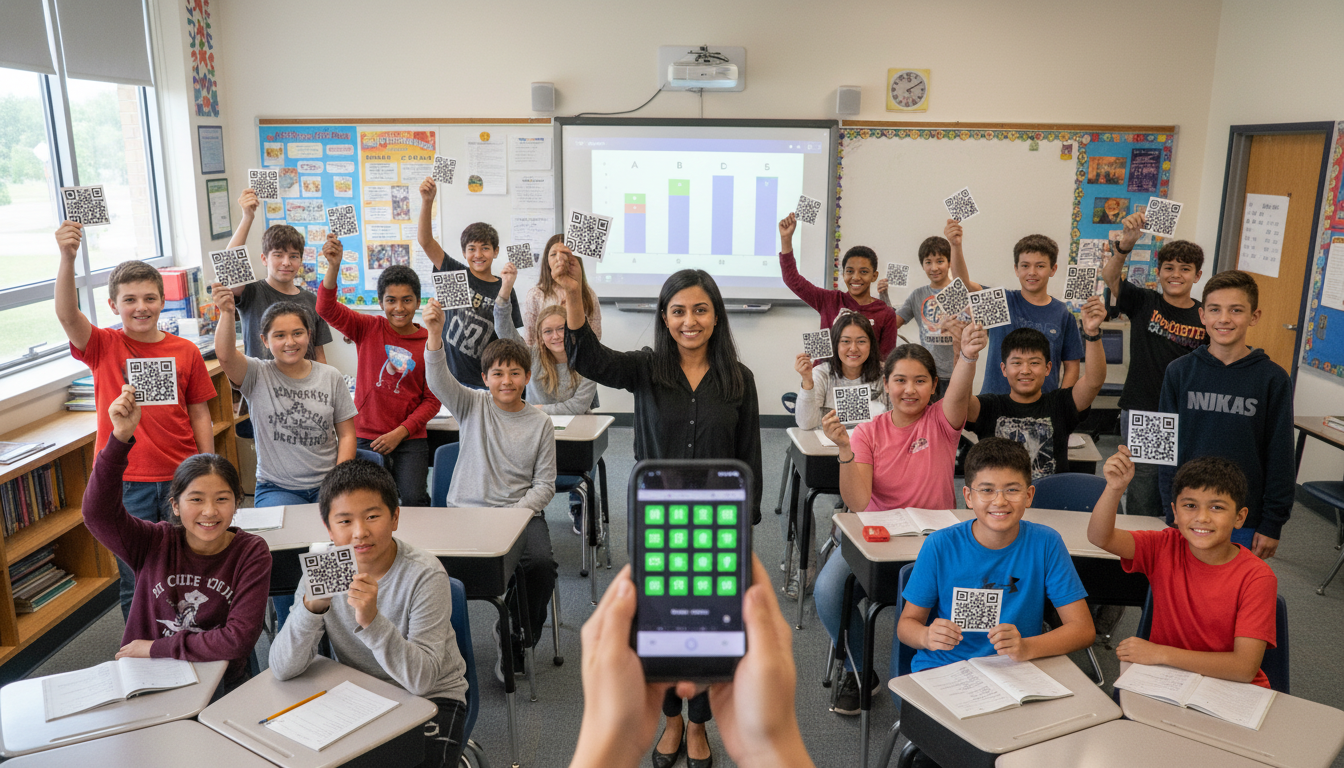

5.1 The Accessibility and Focus Advantage

High-tech polling often fails due to logistical friction: uncharged devices, slow Wi-Fi, forgotten passwords, and the “distraction factor” of placing a tablet in a student’s hands. Plickers eliminates these barriers.

- Zero Login Time: Plickers requires no setup time for students. The cards are always ready.

- Cognitive Focus: Because students are not looking at a screen, their visual attention remains on the teacher and the board. This maintains the “social cohesion” of the classroom, preventing the isolation that occurs when students are buried in devices.

- Privacy: Plickers cards are designed so that the orientation (A, B, C, D) is difficult for neighbors to distinguish. This minimizes peer pressure and “answer copying,” a common issue with raising hands.

5.2 Comparative Efficacy: Clickers vs. Plickers

Studies comparing “Clickers” (electronic remotes) vs. Plickers reveal surprising parity in data collection quality, despite the massive cost difference.

- Compliance: A study found that Plickers achieved a 78% compliance rate, comparable to expensive electronic clickers (87%). While clickers were slightly more “self-explanatory” for students, the cost difference (free paper cards vs. thousands of dollars for clicker sets) makes Plickers the superior choice for most districts.

- Learning Outcomes: Research indicates that the use of response cards (like Plickers) increases “Opportunities to Respond” (OTR). High rates of OTR are strongly correlated with student engagement and academic achievement. In high school settings, the use of Plickers was found to increase academically engaged behavior and decrease disruptive behavior across general education classrooms.

5.3 Formative Assessment and Agile Teaching

The primary value of Plickers is not the grade, but the Data Visualization.

- The Heatmap: Instantly after scanning, the teacher sees a heatmap of student responses. If 80% of the class answers incorrectly, the teacher knows immediately to stop and reteach. This facilitates “Agile Teaching”—the ability to adjust instruction in real-time based on data. Without this tool, a teacher might continue a lesson for 40 minutes, unaware that the students are lost.

- Metacognition: By displaying the anonymous graph to the class (“Look, 50% chose B and 50% chose C”), the teacher can spark rich peer debate. “Why might someone think B is correct?” This moves the locus of control from the teacher to the students, encouraging them to analyze their own thinking.

6. Teacher Action Research: Documenting the Shift

To truly “deepen knowledge” and justify the adoption of these tools, teachers should adopt the stance of a researcher. Action Research involves identifying a problem, implementing an intervention, and rigorously documenting the results. This transforms EdTech from a passive consumption of tools into an active scientific inquiry.

6.1 Methodology for Classroom Testing

Teachers can replicate the methodologies used in the studies cited in this report (e.g., the South High School ISN study) to create their own “Before-and-After” documentation.

- Identify the Variable: Choose one specific intervention (e.g., “Using Google Forms for Weekly Quizzes” or “Implementing Digital Interactive Notebooks”).

- Establish a Baseline (Pre-Data): Collect data from a previous unit or a control group. This could include:

- Quantitative: Average quiz scores, homework completion rates.

- Qualitative: Student surveys on engagement or confidence.

- Workload: A time audit of hours spent grading.

- Intervention: Implement the new tool for a set period (e.g., one unit or 4 weeks).

- Post-Data Collection: Collect the same metrics after the intervention.

- Analysis: Compare the datasets. Did test scores rise? did grading time decrease?

6.2 Case Study: Documenting Workload Reduction

A critical component of this research is focusing on usability and teacher workload.

- The Time Audit Protocol: A teacher can log the time spent grading a specific assignment type (e.g., “Unit Vocabulary Quiz”) using the old method (paper). Then, log the time spent grading the same type of assignment using the new method (Google Forms auto-grading).

- Documenting the Gain: If the audit reveals a reduction from 2 hours to 15 minutes, this is powerful evidence to present to administration or peers. It shifts the conversation from “tech is cool” to “tech is sustainable”.

6.3 Student Feedback as Data

The “usability” of a tool is also defined by the student experience. Teachers should survey students regarding their perception of the tools. For example, in the study regarding audio feedback, student preference data was a key indicator of success. Questions such as “Did the audio feedback help you understand your mistakes better than written comments?” provide qualitative data that validates the pedagogical shift.

7. Conclusion and Future Outlook

The pursuit of “High-Impact” education does not require “High-Tech” infrastructure. In fact, the research suggests an inverse relationship in many contexts: as technological complexity increases, reliability and human connection often decrease. The current obsession with AI and advanced algorithms risks overlooking the profound efficacy of the tools already at our disposal.

This report confirms that ubiquitous, low-tech tools like Google Forms, Slides, and simple audio feedback mechanisms offer a superior pathway for most classrooms. They align with Cognitive Load Theory by reducing interface friction; they support Bloom’s Mastery Learning through branching logic and immediate validation; and they address the critical issue of teacher burnout by automating grading and accelerating feedback.

7.1 Actionable Recommendations for Educators

To implement these findings, educators should follow a phased adoption roadmap focused on depth rather than breadth:

- Phase 1: The Data Culture (Month 1): Implement Plickers for daily bell-ringers. Focus on using the heatmap data to spark class discussion. Document the increase in student participation.

- Phase 2: The Assessment Shift (Month 2): Convert one unit assessment into a Google Form with Branching Logic. Use Response Validation for all short-answer questions. Measure the time saved on grading.

- Phase 3: The Feedback Revolution (Month 3): Replace written comments on major essays with Audio Feedback.

Conduct a student survey to gauge their reception of the voice comments.

- Phase 4: The Interactive Shift (Month 4): Pilot Digital Interactive Notebooks in Slides for a project-based unit. Use the “Before-and-After” slide comparison to visualize learning growth.

By mastering these four tools, a teacher covers the entire instructional cycle—Instruction (Slides), Assessment (Forms/Plickers), and Feedback (Audio)—with zero cost, minimal technical debt, and maximum pedagogical impact. The future of effective teaching is not found in the acquisition of new tools, but in the intentional, minimalist optimization of the ones we already possess.