TPACK Framework: Effective Technology Integration in Education

Executive Synthesis: The Intersection of Tools, Teaching, and Truth

The integration of digital technology into the educational landscape has historically been characterized by a cyclical pattern of euphoric hype, substantial capital investment, and subsequent pedagogical disillusionment. This phenomenon, frequently categorized in academic literature as “technocentrism,” is predicated on the reductive assumption that the mere introduction of sophisticated hardware—be it the personal computers of the 1980s, the interactive whiteboards of the 1990s, or the tablets and artificial intelligence of the 21st century—will spontaneously catalyze a revolution in student learning and instructional efficacy. However, the empirical record of the last four decades suggests a divergent reality: without a robust theoretical framework to guide integration, technology often remains an expensive distraction or a superficial overlay on traditional teaching methods.

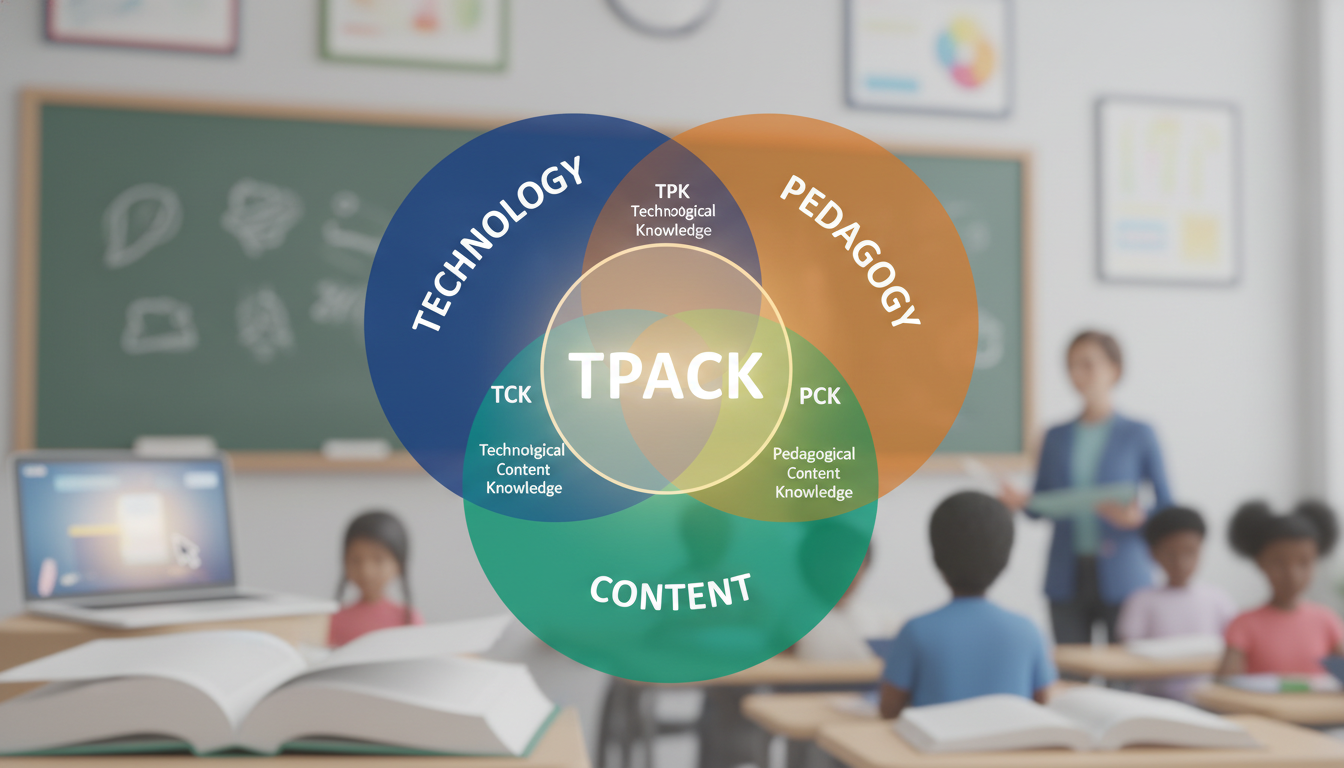

The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework, introduced by Mishra and Koehler and rooted in Shulman’s construct of Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK), provides the necessary corrective lens. TPACK posits that effective technology integration is not a function of technological fluency alone, but rather an emergent form of knowledge located at the volatile intersection of Content (what is taught), Pedagogy (how it is taught), and Technology (the tools used). It reframes teaching with technology from a technical skill to a “wicked problem”—a complex, context-dependent challenge that requires constant design and renegotiation by the educator.

This report offers an exhaustive analysis of the TPACK framework. It dissects the anatomy of high-profile adoption failures to illustrate the consequences of ignoring TPACK, details the theoretical architecture and recent evolution of the model (including the critical addition of Contextual Knowledge, or XK), examines the methodologies for developing this integrated knowledge in practitioners, and provides granular, domain-specific case studies of TPACK in action.

1. The Pathology of Failure: When Technology Eclipses Pedagogy

To understand the necessity of the TPACK framework, one must first examine the educational landscape where its principles were absent. The history of educational technology adoption is littered with initiatives that treated hardware as a silver bullet, ignoring the complex triangulation of pedagogy and content required for success. These failures were not merely logistical; they were epistemological, rooted in a fundamental misunderstanding of how teaching occurs.

1.1 The “One Laptop Per Child” (OLPC) Paradox

The One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) project, announced in 2005 by Nicholas Negroponte of the MIT Media Lab, serves as the definitive case study in technocentric failure. The initiative was driven by a humanitarian and utopian vision: to distribute low-cost, rugged laptops (the XO) to children in developing nations, operating under the assumption that access to connected devices would inherently bridge the educational divide and lift populations out of poverty.

The “Charisma Machine” and the Pedagogical Void

Morgan Ames, in her critical analysis of the project, describes the XO laptop as a “charisma machine”—a device whose symbolic power blinded its creators to the realities of its use. The project was fundamentally flawed because it prioritized the distribution of hardware over the development of curriculum or teacher training.

- The “Technically Precocious Boy” Bias: The design of the XO laptop assumed a user profile similar to the developers themselves—curious, self-directed tinkerers who would learn by exploration. This “constructionist” ideal failed to account for the diverse pedagogical needs of the actual student population, many of whom required structured guidance to engage with the device meaningfully.

- Marginalization of the Teacher: In many implementations, such as those in Peru and Paraguay, the project explicitly bypassed the teacher, viewing them as potential barriers to the “digital revolution.” Consequently, teachers were given little to no training on how to integrate the devices into their existing curricula. The result was anxiety and insecurity; teachers feared a loss of control in the classroom and often forbade the use of the laptops during instructional time.

- Disconnect from Content: The laptops were often treated as separate from the core subject matter. Longitudinal research in Peru indicated that while students gained “technological fluency” (TK) and cognitive skills related to the device, there was no significant improvement in Mathematics or Language scores (CK) because the technology was not leveraged to teach that content specifically.

The failure of OLPC was not a failure of processing power or battery life; it was a failure of TPACK. The initiative provided the “T” (Technology) in abundance but ignored the “P” (Pedagogy) and “C” (Content), and critically, failed to facilitate the interaction between them.

1.2 The LAUSD iPad Initiative: A Crisis of Context and Isomorphism

Domestically, the 2013 attempt by the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) to provide every student with an iPad further illustrates the dangers of isolating technology from pedagogical strategy. This initiative collapsed under the weight of logistical failures, security breaches, and a lack of instructional vision.

Institutional Isomorphism and the Rush to Adopt

The LAUSD rollout can be viewed through the lens of “institutional isomorphism”—the tendency of organizations to mimic one another to appear legitimate. The pressure to adopt “21st-century learning” tools led the district to deploy thousands of devices without a clear pedagogical roadmap.

- The Content Gap: The devices came pre-loaded with Pearson curriculum content, but this content was often essentially digital textbooks—static PDFs that did not leverage the interactive affordances of the iPad. This represents a failure of Technological Content Knowledge (TCK); the technology did not transform the representation of the content.

- The Pedagogy Gap: Teachers were not equipped with Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK). They did not know how to manage the “distractions” of the device or how to use it for collaborative learning. Consequently, students quickly bypassed security filters to access social media and games, leading the district to reclaim the devices. The initiative failed to transform the “digital divide” into digital learning, instead creating a “usage divide” where technology was present but pedagogically inert.

| Feature | One Laptop Per Child (Global) | LAUSD iPad Initiative (USA) | TPACK Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Driver | Humanitarian/Utopian Vision; “Technological Determinism” | Equity/Access Standards; “Institutional Isomorphism” | Technocentric motivation ignored pedagogical strategy. |

| Teacher Role | Marginalized; assumed irrelevant or obstructive | Undermined; lack of voice in planning | Failure to develop TPK (Technological Pedagogical Knowledge). |

| Curriculum | Constructionist “tinkering” (unstructured) | Pearson pre-loaded content (digitized traditional) | Content was static or disconnected from tech (Low TCK). |

| Outcome | No academic gains; limited adoption; abandoned | Security breaches; refund suit; recall of devices | Integration failed due to lack of Contextual Knowledge (XK) and TPK. |

The consistent theme across these failures is the isolation of the technology variable. In both cases, the planners assumed that the technology itself carried the pedagogy. TPACK refutes this, arguing that the technology is neutral until it is activated by a pedagogical intent anchored in specific content.

2. The Theoretical Architecture: Deconstructing the Framework

The TPACK framework was developed to provide the missing theoretical structure highlighted by the failures above. It builds upon Lee Shulman’s seminal 1986 concept of Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK)—the idea that teaching a subject requires a special blend of content and pedagogy unique to that discipline. A history teacher does not teach “critical thinking” in the abstract; they teach “historical thinking” using specific pedagogical tools like document analysis. Mishra and Koehler extended this by introducing Technology as a third distinct knowledge domain, resulting in a complex interaction of seven components.

2.1 The Three Core Knowledge Domains

The framework is visualized as three overlapping circles. While these definitions may seem elementary, their specific boundaries are crucial for the integrity of the model.

-

Content Knowledge (CK): The teacher’s knowledge about the subject matter to be learned or taught. This includes concepts, theories, ideas, organizational frameworks, evidence, and proof.

Example: For a biology teacher, CK involves a deep understanding of the Krebs cycle, not just as a diagram, but as a chemical process. For a math teacher, it is the understanding of the properties of linear functions.

Implication: Without deep CK, technology becomes a mask for superficiality. A teacher might use a flashy presentation tool, but if the underlying content is factually incorrect or conceptually shallow, the technology amplifies the error.

-

Pedagogical Knowledge (PK): The deep knowledge about the processes and practices or methods of teaching and learning. This encompasses overall educational purposes, values, and aims.

Example: Understanding classroom management, lesson planning, student assessment, and learning theories such as constructivism, behaviorism, or socio-emotional learning.

It involves knowing how students learn, independent of what they are learning.

Technological Knowledge (TK)

- Knowledge about certain ways of thinking about, and working with, technology, tools, and resources. This includes understanding information technology broadly enough to apply it productively at work and in everyday life.

- Example: Knowing how to operate an interactive whiteboard, how to troubleshoot a Wi-Fi connection, or how to install a software application. Importantly, this definition sees TK as “developmental,” evolving over a lifetime of interaction with technology, rather than a fixed end-state.

The Intersections: The Locus of Integration

The true power of the TPACK model lies not in the circles themselves, but in the specific areas where they intersect. These intersections represent the nuanced, specialized knowledge required for effective integration.

Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK)

Definition: The knowledge of pedagogy that is applicable to the teaching of specific content. This is Shulman’s original construct.

Application: A history teacher knowing that “role-playing” is an effective strategy for teaching the complex diplomacy of the Treaty of Versailles, or a math teacher knowing the common misconceptions students have about negative numbers. This domain exists without technology and is the foundation of good traditional teaching.

Technological Content Knowledge (TCK)

Definition: An understanding of the manner in which technology and content influence and constrain one another. It involves understanding how the subject matter can be represented through technology.

Application: A geographer understanding how GIS (Geographic Information Systems) software changes the way spatial data is visualized and interpreted. It involves knowing that the technology (GIS) allows for the representation of the content (Geography) in layers, which was impossible with paper maps. It is the understanding of the tool’s impact on the discipline itself. The technology is not just a delivery vehicle; it changes the nature of the content.

Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK)

Definition: An understanding of how teaching and learning can change when particular technologies are used in particular ways. This knowledge applies across disciplines.

Application: A teacher knowing that using a digital whiteboard allows for collaborative editing, which supports a social-constructivist teaching style. It involves understanding the pedagogical affordances and constraints of a tool (e.g., “Zoom allows for breakout rooms, which facilitates small group discussion, but inhibits non-verbal cues”).

Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)

Definition: The basis of effective teaching with technology. It requires an understanding of the representation of concepts using technologies; pedagogical techniques that use technologies in constructive ways to teach content; knowledge of what makes concepts difficult or easy to learn and how technology can help redress some of the problems that students face.

Insight: TPACK is an “emergent form of knowledge.” It is distinct from the sum of its parts. A teacher with high TPACK does not just know the subject, the teaching method, and the tool; they know how to synthesize them to solve a specific instructional problem. It is the knowledge required to navigate the “wicked problem” of teaching.

The Evolution of Context: From a Dotted Line to “XK”

One of the most significant theoretical evolutions in the TPACK framework concerns the role of Context. In early visualizations, context was represented by a dotted circle surrounding the three knowledge domains. This representation was often criticized for treating context as a passive container or a boundary condition rather than an active, determining force.

The 2019 Update: Contextual Knowledge (XK)

In response to these critiques, Punya Mishra reconceptualized context as a distinct knowledge domain: Contextual Knowledge (XK). This shift moves context from the background to the foreground of the framework.

Definition: XK encompasses a teacher’s understanding of the specific organizational and situational constraints they work within. It includes:

- Micro-level: The specific students in the classroom (special needs, language proficiency, prior knowledge).

- Meso-level: The school culture, the availability of technical support, the rigidness of the curriculum, and the leadership style of the administration.

- Macro-level: The socio-political environment, national standards, and the broader digital equity landscape.

Significance: This update asserts that a teacher cannot possess “TPACK” in a vacuum. A lesson plan that demonstrates high TPACK in a resource-rich, suburban high school (1:1 iPads, high bandwidth) may demonstrate low TPACK in a rural school with limited connectivity or a strict prohibition on mobile devices. The “success” of the integration is entirely dependent on the teacher’s knowledge of the context (XK).

The Intrapreneurial Teacher: With XK, the teacher is viewed as an “intrapreneur”—someone who knows how the organization functions and how to pull levers of power to effect change. Success depends not just on knowing the tool (TK) but on knowing if the school’s firewall will block it (XK) or if the administration will support a noisy, project-based classroom (XK).

Table 2: Evolution of Context in TPACK

| Model Feature | Original Framework | Updated Framework (Mishra, 2019) |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Representation | Dotted circle surrounding the Venn diagram. | A distinct domain (XK) encompassing the Venn diagram. |

| Conceptualization | Context as a boundary or container. | Context as an active knowledge domain (XK). |

| Teacher Agency | Implicit; teacher works within context. | Explicit; teacher must know and navigate context. |

| Key Insight | “Context matters.” | “Contextual Knowledge is a prerequisite for integration.” |

Critiques, Limitations, and the Measurement Conundrum

Since its inception, the TPACK framework has been subjected to rigorous scrutiny. While widely accepted as a conceptual tool, its practical application and measurement have faced significant challenges.

Theoretical Ambiguity and “Fuzzy Boundaries”

Conceptual Complexity: Critics argue that the framework is conceptually confusing and that teachers (and researchers) struggle to distinguish between TPK and TPACK in practice. For instance, when a teacher uses a simulation to teach physics, is that TCK (physics represented by tech) or TPK (tech supporting a pedagogical strategy)? The answer often depends on the intent of the teacher, which is difficult to observe.

The “Technocentric” Critique: Some scholars argue that by giving “Technology” its own circle equal to Pedagogy and Content, the framework inadvertently privileges technology, elevating it to a foundational status it may not deserve. They argue for a more “instrumentalist” view where technology is merely a subset of resources within Pedagogy. However, TPACK proponents argue that in the 21st century, digital technologies have become so ubiquitous and transformative that they warrant a distinct domain.

Challenges in Measurement

Developing valid and reliable assessment instruments for TPACK has proven to be a “wicked problem” in itself.

Self-Report Surveys: The vast majority of TPACK research relies on self-report surveys (e.g., “I feel confident using technology to teach math”).

- Validity Issues: These surveys measure self-efficacy (confidence), not actual knowledge or performance. A teacher may believe they are integrating technology effectively because they use it frequently, even if the pedagogical quality is low. Research has shown that teachers often over-estimate their TPACK when self-reporting.

- Factor Analysis: Statistical analyses of these surveys often fail to distinguish the seven factors clearly. Teachers often conflate TPK, TCK, and TPACK, viewing them as a singular competency of “using tech in class”.

Performance-Based Assessment: To address these limitations, researchers are moving toward performance-based assessments, such as analyzing lesson plans, classroom observations, and portfolios using standardized rubrics. While more valid, these methods are resource-intensive and hard to scale.

Developing TPACK: Beyond the “Skill-and-Drill” Workshop

If TPACK is the required knowledge base, how is it acquired? The history of professional development (PD) in EdTech has been dominated by “skill-and-drill” workshops—sessions focused on the mechanical operation of software (TK) in isolation from content or pedagogy. The research indicates this approach is largely ineffective for fostering true integration.

The “Learning by Design” Methodology

Mishra and Koehler advocate for a “Learning by Design” (LbD) approach to TPACK development. This methodology shifts the teacher’s role from a passive recipient of technical training to an active designer of educational artifacts.

Mechanism: When teachers work collaboratively to design a lesson or unit that integrates technology, they are forced to confront the frictions between the tools, the content, and the pedagogy. The design process itself generates the knowledge. It is “learning by doing” applied to curriculum design.

The LbD Protocol: A typical LbD workshop involves specific phases:

- Exploration: Teachers play with a technology to understand its affordances (TK) without a specific goal.

- Problem Identification: Teachers identify a specific “pedagogical problem” in their subject area (e.g., “Students don’t understand the scale of the solar system” – CK/PCK).

- Design: Teachers collaborate to create a solution using the technology. They must justify why this tool solves that problem (TPACK).

- Reflection/Critique: Teachers enact the lesson or present it to peers for feedback, refining the alignment of T, P, and C.

5.2 Activity Types: Bridging Theory and Practice (Harris & Hofer)

To make the abstract concepts of TPACK more accessible, researchers Judi Harris and Mark Hofer developed the concept of Learning Activity Types (LATs). This taxonomy helps teachers connect their curriculum goals directly to technological choices, bypassing the paralysis that often comes with abstract theory.

- The “Grounded” Approach: Instead of starting with the question “How do I use this iPad?”, the teacher starts with “What learning activity do I need?” (e.g., “I need students to interpret a data set”). The taxonomy then suggests technologies that support that specific activity.

The Taxonomy Structures

Harris and Hofer developed comprehensive taxonomies for various disciplines. These are critical tools for operationalizing TPACK.

| Activity Genre | Activity Type | Description | Compatible Technology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consider | Attend to a Demonstration | Students gain info from a presentation or animation. | Interactive Whiteboard, Video Clip, Document Camera |

| Practice | Practice for Fluency | Students practice computational skills to build speed/accuracy. | Online drill-and-practice games, Math Blaster, Flashcard apps |

| Interpret | Interpret a Representation | Students explain relationships in a graph, table, or model. | Virtual Manipulatives, Excel/Sheets, Desmos, GeoGebra |

| Produce | Produce a Representation | Students generate a graph or model to represent data. | Graphing Calculators, Spreadsheet software |

| Activity Genre | Activity Type | Description | Compatible Technology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Building | Virtual Field Trip | Students virtually visit a location to gather info. | Google Earth, VR Headsets, Museum Virtual Tours |

| Convergent Expression | Timelines/Sequencing | Students order events chronologically. | Tiki-Toki, Timeline JS, interactive whiteboard |

| Divergent Expression | Digital Storytelling | Students create a narrative combining audio/visuals. | iMovie, WeVideo, Podcasting tools |

| Participatory | Civic Action | Students engage with gov’t or community. | Email campaigns, Blogs, Social Media advocacy |

By using these taxonomies, teachers “scaffold” their TPACK development. They don’t need to know every technology; they only need to know the ones that support their chosen activity type.

6. TPACK in Action: In-Depth Classroom Case Studies

The theoretical constructs of TPACK crystallize when observed in specific disciplinary contexts. The following case studies demonstrate how TPACK manifests in the classroom, contrasting “Technocentric” (Low TPACK) approaches with “Integrated” (High TPACK) strategies.

6.1 Mathematics: Dynamic Visualization with Desmos

Context: An 8th-grade Algebra class learning about Linear Equations, specifically the Slope-Intercept Form ($y = mx + b$).

- The Instructional Problem (PCK): Students often memorize the formula $y=mx+b$ without understanding what the variables $m$ (slope) and $b$ (y-intercept) actually represent visually. They view the equation as a static calculation rather than a dynamic relationship.

Approach A: The Technocentric Method (Low TPACK)

- Activity: The teacher projects a Khan Academy video explaining slope. Students then use an iPad app to complete a digital worksheet where they calculate the slope between two static points.

- Critique: The technology is used merely as a delivery mechanism and a substitution for paper. The representation of the math is static. The pedagogy is passive consumption.

- Result: Students may learn to calculate, but they lack conceptual depth regarding the behavior of the function.

Approach B: The Integrated TPACK Method (Desmos “Marbleslides”)

- Activity: The teacher uses the “Marbleslides: Lines” activity from Desmos.

- The Mechanism: The screen displays a set of stars and a “launch” point for marbles. Students are given an equation (e.g., $y = 2x + 1$). When they click “Launch,” marbles fall along the line. They must change the numbers in the equation to reshape the line so the marbles hit all the stars.

- TPACK Analysis:

- Technology (TK): The teacher leverages the dynamic graphing engine which allows for real-time manipulation of variables.

- Content (CK/TCK): The activity directly targets the relationship between parameters and graph shape. Students see that changing $m$ rotates the line and changing $b$ translates it. The technology represents the math in a way paper cannot (dynamic transformation).

- Pedagogy (PK/TPK): The strategy is “Gamified Inquiry.” Students are not told the rules; they discover them through trial and error. The immediate feedback loop of the marbles serves as a formative assessment.

- Outcome: Students develop an intuitive, deep understanding of the equation. They are doing math, not just calculating it.

6.2 Social Studies: Constructing History via Digital Storytelling

Context: High School History, The Great Depression.

- The Instructional Problem (PCK): Students struggle to empathize with historical figures or understand the “human element” behind the economic statistics.

Approach A: The Technocentric Method (Low TPACK)

- Activity: Students research the Great Depression on Wikipedia and write a 3-page essay in Microsoft Word, inserting clip art images of breadlines.

- Critique: This is a traditional report typed on a computer. The technology adds efficiency but does not deepen the historical thinking.

Approach B: The Integrated TPACK Method (Digital Documentary)

- Activity: Students create a 5-minute “Digital Story” or mini-documentary. They must curate primary source audio (e.g., FDR’s fireside chats, oral histories) and photographs (e.g., Dorothea Lange). They write a script that weaves these sources into a narrative argument.

- TPACK Analysis:

- Technology (TK): Using video editing software (WeVideo/iMovie) to layer audio, visual, and text tracks.

- Content (CK/TCK): The core skill is historiography—selecting evidence to build a narrative. The multimodal nature of the video forces students to analyze the mood and tone of primary sources, not just the facts.

- Pedagogy (PK/TPK): The approach is Constructionist. Students “build” history. The teacher scaffolds the process by teaching scriptwriting (literacy) and copyright ethics (digital citizenship). The product is public (shared with the class/web), which increases student motivation.

- Outcome: Students engage in “deep viewing” and “deep listening” of sources. They understand history as a constructed narrative rather than a list of dates.

6.3 Science: From Static Models to Virtual Reality

Context: 7th Grade Life Science, Cell Anatomy.

- The Instructional Problem (PCK): Students struggle to understand the 3-dimensional complexity of a cell and the functional relationships between organelles (systems thinking).

Approach A: The Technocentric Method (Low TPACK)

- Activity: The teacher uses a SmartBoard to label a 2D diagram of a cell. Students take a quiz on a Learning Management System (LMS) matching organelles to definitions.

- Critique: The SmartBoard is just an expensive overhead projector. The assessment is low-level recall.

Approach B: The Integrated TPACK Method (VR/AR Simulation)

- Activity: Students use Google Expeditions or a similar VR tool to “enter” a cell. They guide a “tour” for their partner, explaining the function of the mitochondria as they “pass” it. Alternatively, they create a stop-motion animation of protein synthesis using play-dough and phone cameras.

- TPACK Analysis:

- Technology (TK): VR or Animation software.

- Content (CK/TCK): The content is spatial and process-oriented. VR addresses the spatial misconception (cells are 3D, not flat circles). Animation addresses the process misconception (cellular functions happen over time).

- Pedagogy (PK/TPK): Situated Learning. The student experiences the environment. In the animation example, the pedagogy is “learning by teaching/creating.”

- Outcome: Students visualize the cell as a living system. The technology makes the invisible visible.

6.4 English Language Arts: Social Annotation and Visible Thinking

Context: High School Literature, reading a complex novel (e.g., The Great Gatsby).

- The Instructional Problem (PCK): Students struggle with close reading and often gloss over complex passages. Class discussions are dominated by a few extroverted students.

Approach A: The Technocentric Method (Low TPACK)

- Activity: Students read the e-book version on their tablets.

- Critique: This is functionally identical to reading a paperback, perhaps worse due to eye strain.

Approach B: The Integrated TPACK Method (Social Annotation)

- Activity: The text is loaded into a social annotation platform like Perusall or a shared Google Doc. Students are required to highlight passages and leave comments/questions in the margins. They must reply to at least two peers’ comments.

- TPACK Analysis:

- Technology (TK): Cloud-based collaborative text editing.

- Content (CK/TCK): Literary analysis and critical reading.

- Pedagogy (PK/TPK): Social Constructivism. The technology makes thinking visible. The teacher can see the “heat map” of where students are confused (based on where they comment) and adjust the next day’s lesson (Just-in-Time Teaching).

- Outcome: Students engage in “deep viewing” and “deep listening” of sources. They understand history as a constructed narrative rather than a list of dates.

The solitary act of reading becomes a communal dialogue.

- Outcome: The “quiet” students participate equally in the margins. The class discussion starts at a higher level because the basic comprehension work happened asynchronously.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge framework serves as the essential scaffolding for modern education. By moving beyond the simplistic allure of hardware (Technocentrism) and insisting on the complex integration of tools, teaching methods, and subject matter, TPACK provides a robust explanation for past failures and a roadmap for future success.

Key Takeaways

- Rejection of Isolation: Technology, Pedagogy, and Content cannot be treated as separate silos. The efficacy of EdTech lies entirely in the intersections (TCK, TPK, TPACK). A “computer lab” separate from the classroom is the architectural embodiment of low TPACK.

- The Primacy of Context (XK): The 2019 inclusion of Contextual Knowledge transforms TPACK from a static model into a dynamic, ecological framework. Effective integration is situational; it is a “wicked problem” that must be solved daily by the teacher based on their specific students and resources.

- Design as Professional Development: Teachers develop TPACK not through instruction about technology (workshops on software menus), but through the active design of technology-enhanced curriculum. The “Learning by Design” approach builds the necessary professional wisdom to navigate the intersections of knowledge.

- Activity Types as a Bridge: The Harris & Hofer taxonomies provide the practical link between high theory and daily lesson planning, allowing teachers to select tools based on pedagogical intent rather than novelty.

The Future of TPACK in the AI Era

As educational technologies evolve toward Artificial Intelligence and adaptive learning systems, the TPACK framework faces its next great test. The “Technology” circle is becoming agentic, capable of taking over aspects of “Pedagogy” (via automated tutoring systems) and “Content” (via generative AI like ChatGPT).

- The Challenge: If the technology can “teach” and “create content,” what is the role of the teacher’s TPACK?

- The Outlook: Future research suggests that Contextual Knowledge (XK) and Pedagogical Knowledge (PK) will become even more critical. While AI can simulate content delivery, it lacks the deep XK to understand the emotional and social needs of the specific child. The teacher’s role shifts from a content delivery mechanism to a “Learning Experience Designer” who orchestrates the interplay between AI tools, human interaction, and rigorous content standards.

Ultimately, TPACK validates the profession of teaching. It demonstrates that effective teaching with technology is not a matter of simply “turning it on,” but a sophisticated intellectual achievement that requires the constant, creative synthesis of diverse bodies of knowledge. It is, and will remain, a deeply human endeavor.