Boost Professional Development Quality: Close the Knowing-Doing Gap

The Crisis of Efficacy in Organizational Learning

The Transfer Paradox

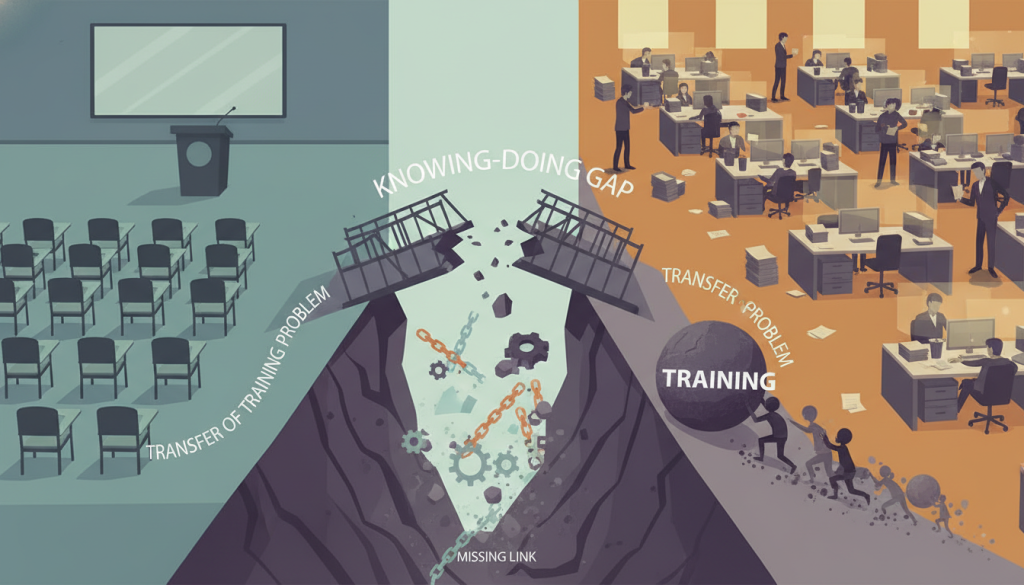

In the contemporary landscape of human capital development, a profound and costly paradox exists. Organizations, ranging from multinational corporations to K-12 educational districts, invest billions annually in the professional growth of their workforce. The stated objective of this investment is clear: to enhance performance, foster innovation, and improve outcomes, whether those outcomes are measured in quarterly profits or student standardized test scores. Yet, the empirical reality of this investment stands in stark contrast to its ambitions. This phenomenon, widely categorized in academic literature as the “transfer of training problem,” represents a systemic failure in the architecture of modern professional development.

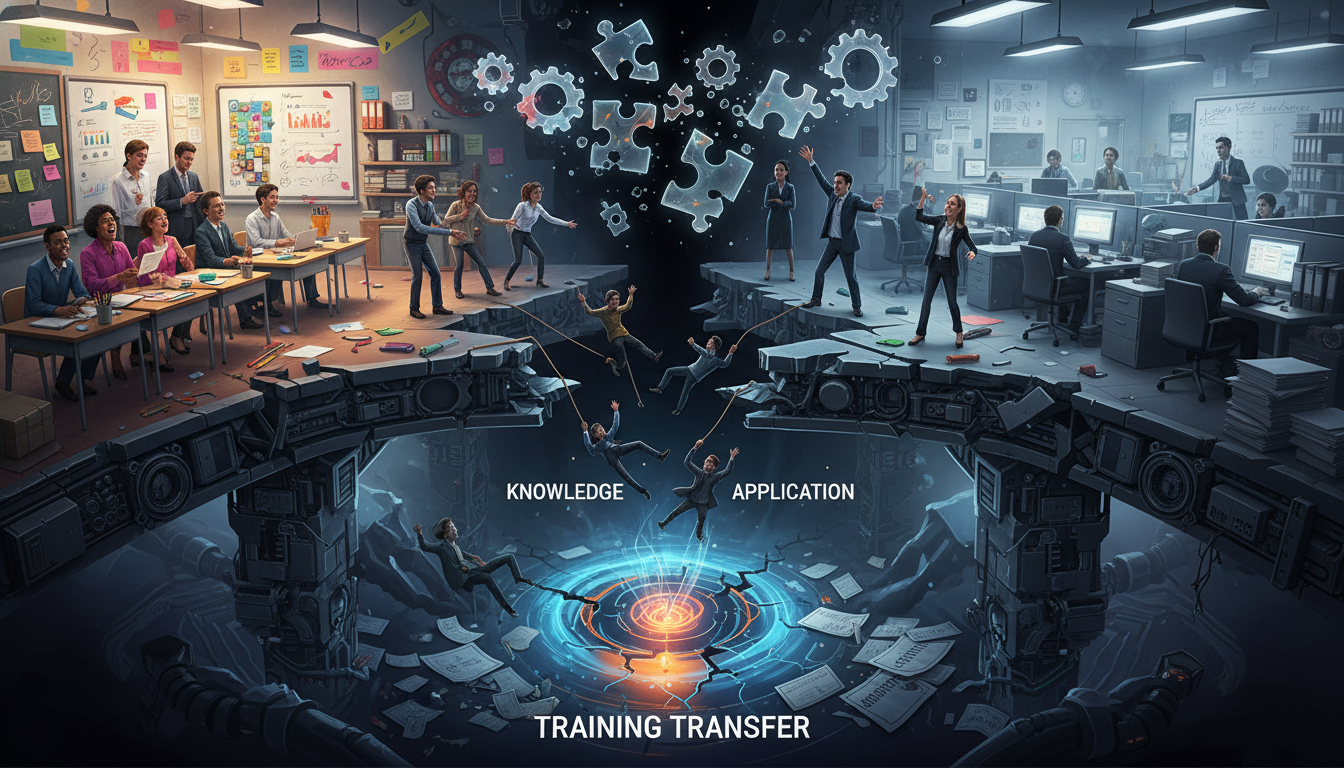

The transfer of training is defined as the effective and continuing application of the knowledge, skills, and behaviors gained in training to the job context. It is the bridge between the “seminar room” and the “operating room,” the classroom, or the boardroom. However, the structural integrity of this bridge is historically compromised. Research from the Association for Talent Development indicates a staggering inefficiency: only approximately 12% of employees effectively apply new skills learned in training to their daily professional tasks. This statistic implies a wastage rate of nearly 90%, suggesting that the vast majority of resources allocated to traditional training act as a “sunk cost” with no tangible return on investment.

The gravity of this situation is compounded by a pervasive lack of awareness among organizational leaders regarding the depth of the failure. According to research by the Institute for Corporate Productivity, only 35% of organizations have formal processes in place to measure the transfer of learning. Consequently, two-thirds of organizations are operating in a state of blind optimism, assuming that attendance at a workshop equates to competence in the workplace. This absence of systematic evaluation means organizations are potentially “flying blind,” continuing to fund ineffective interventions because they lack the data to diagnose the pathology of their learning systems.

The “Sisyphus” Effect and the Workshop Model

The dominant modality for professional development remains the “one-off” workshop—a discrete, time-bound event where an expert disseminates information to a passive audience. This model persists not because of its efficacy, but because of its administrative convenience and scalability. It is far easier to schedule a keynote speaker for a single day than it is to engineer a complex, longitudinal system of peer inquiry and coaching. However, the reliance on this model has created what researchers describe as a “Sisyphus” effect.

Like the mythical figure condemned to roll a boulder up a hill only to watch it roll back down, educators and professionals are frequently subjected to cyclical, low-impact training that rarely changes practice. The research of Bruce Joyce and Beverly Showers, spanning decades of inquiry into teacher development, provides the most damning quantitative indictment of this model. Their data reveals that when training consists solely of theory, demonstration, and practice during the session—the standard components of a good workshop—participants may achieve a high level of understanding (up to 90% skill acquisition during the session). However, the rate of transfer to actual practice is a negligible 5%.

This “5% threshold” creates a culture of cynicism. When professionals are repeatedly exposed to initiatives that vanish without support, they develop “initiative fatigue.” They learn that the rational response to new training is to wait it out, knowing that without sustained follow-up, the demand for change will dissipate. This is not necessarily an act of rebellion, but a rational adaptation to an environment that demands change without providing the scaffolded support necessary to achieve it.

The 70-20-10 Heuristic and Misconceptions

In an attempt to rectify the failures of formal training, the Learning and Development (L&D) sector has largely embraced the 70-20-10 model. Originating from research at the Center for Creative Leadership, this framework posits that 70% of learning is derived from challenging assignments and on-the-job experiences, 20% from developmental relationships (such as mentoring and coaching), and only 10% from formal coursework and training.

While this model provides a useful corrective to the over-reliance on formal courses, it is often misinterpreted as a justification for minimizing investment in structured learning. Some organizational leaders view the “10%” figure as evidence that formal training is obsolete. However, critics argue that this view is “beguiling” and dangerous. The 70-20-10 model describes how leaders learn, not necessarily how they should be supported. The components are symbiotic, not independent. The “10%” of formal training provides the necessary schematic framework—the shared language and theory—that allows the “70%” of experience to be processed effectively.

Without the foundational knowledge provided by formal training, on-the-job experience can simply reinforce bad habits. Furthermore, the “20%” of coaching is the catalytic agent that converts experience into wisdom. Research suggests that on-the-job learning has three times more impact on employee performance than formal training, but only when supported by the reflective capacity that coaching provides. Therefore, the solution to the transfer problem is not to abandon training (the 10%) but to aggressively build the ecosystem of coaching (the 20%) that bridges the gap to experience (the 70%).

The Pathology of the “Spray and Pray” Approach

The Disconnect Between Acquisition and Application

The fundamental flaw of the “spray and pray” approach—where information is sprayed over an audience with the prayer that it sticks—lies in its failure to account for the cognitive and environmental barriers to transfer. Transfer breaks down into three types: using previous knowledge to aid new learning, applying past learning to new situations, and transferring learning to on-the-job tasks. The traditional workshop excels at the first (activating prior knowledge) but fails catastrophically at the third (application).

The disconnect is driven by the specific nature of the transfer problem. Often, the training context (a quiet conference room, theoretical case studies) bears little resemblance to the performance context (a chaotic classroom, a high-pressure trading floor). This lack of “fidelity” between the training environment and the work environment creates a cognitive gap that most learners cannot bridge independently. Baldwin and Ford categorized the transfer literature into input factors, including trainee characteristics, training design, and work environment. The workshop model addresses training design but ignores the trainee’s readiness and the work environment’s receptivity to change.

Furthermore, the “implementation dip” is a critical psychological phenomenon ignored by one-off training. When a practitioner tries a new skill, performance almost invariably dips before it improves. The new method feels clumsy, time-consuming, and ineffective compared to the old, ingrained habit. Without a coach to normalize this dip and provide feedback, the learner interprets the struggle as failure and reverts to the old practice. One-off workshops provide motivation before the dip, but vanish exactly when the learner enters the “valley of despair.”

The Economics of Ineffectiveness

From a financial perspective, the reliance on ineffective training models represents a massive misallocation of resources. When analyzing the cost-benefit ratio of different PD modalities, workshops appear cheaper upfront but are exorbitantly expensive when measured by cost-per-unit-of-change.

A comparative cost analysis of workshops versus coaching interventions highlights this disparity. The marginal cost—the cost for one additional participant—at a traditional workshop ranges from $663 to $1,132 when factoring in registration, travel, and lost productivity. In contrast, the marginal cost for coaching an additional peer teacher within a school building is approximately $441.

When one overlays the effectiveness rates (5% for workshops vs. 75-90% for coaching) onto these costs, the “expensive” coaching model becomes the only fiscally responsible option. Spending $1,000 for a 5% chance of success is a gamble; spending $2,000 for a 90% chance of success is an investment. Studies on the cost-effectiveness of instructional coaching using design-based implementation research show that while initial costs are high, the cost per successful outcome decreases substantially over time as the coaching model stabilizes and capacity is built internally. Conversely, the workshop model represents a perpetual “renting” of external expertise with no asset accumulation in the form of internal capacity.

The “Mirage” of Professional Development

The report “The Mirage” famously critiqued the status quo, noting that school districts spend billions on PD with no evidence of improvement in teacher practice or student learning. The “Mirage” is the belief that because activity is happening—workshops are booked, sign-in sheets are filled—learning is occurring.

This illusion is maintained by the metrics used to evaluate training.

Most organizations rely on “Level 1” evaluation (participant reaction) under the Kirkpatrick model—did the participants like the training? High satisfaction scores on these “happy sheets” are often inversely correlated with learning, as rigorous, challenging training often produces lower immediate satisfaction than entertaining, passive presentations. By optimizing for satisfaction rather than impact, organizations perpetuate a cycle of comfortable ineffectiveness.

3. Theoretical Foundations: Andragogy and Transformation

To design effective professional development, one must first accept that the pedagogical strategies used for children are often counterproductive for adults. Malcolm Knowles, the father of andragogy (adult learning theory), argued that as individuals mature, their psychological relationship to learning shifts fundamentally. He proposed six key assumptions that distinguish adult learners, all of which argue against the passive workshop model.

3.1 Malcolm Knowles and the Distinct Nature of the Adult Learner

Adults need to understand why they need to learn something before they are willing to invest energy in it. In compulsory schooling (pedagogy), the justification “because it’s on the test” suffices. In the professional world, learners demand relevance. They unconsciously weigh the “value of learning” against the “cost of learning” (time, effort, ego). If the “why” is not established immediately and tied to their reality, they disengage.

3.1.2 The Self-Concept

As people mature, their self-concept moves from dependency toward self-direction. Adults have a deep psychological need to be perceived and treated as capable of taking responsibility for themselves. Traditional training, which places the adult in a dependent role (sitting in rows, listening to a lecture), creates a conflict with this self-concept. This leads to resentment and resistance. Effective PD must be facilitative rather than didactic, treating the learner as a partner in the inquiry rather than a vessel to be filled.

3.1.3 The Role of Experience

Adults enter the learning environment with a vast reservoir of experience. In pedagogy, the learner’s experience is minimal, so the teacher’s experience is the primary resource. In andragogy, the learner’s experience is the richest resource. Training that ignores this experience—treating experts as novices—is perceived as insulting. Techniques that tap into this experience, such as peer discussions, case studies, and reciprocal mentoring, honor the learner’s history and facilitate connection to new concepts.

3.1.4 Readiness to Learn

Adults become ready to learn those things that they need to know to cope effectively with their real-life situations. Readiness is induced by the need to perform a task or solve a problem. It is developmental; a new manager is ready to learn about conflict resolution in a way that a veteran manager (or a non-manager) is not. “One-size-fits-all” training ignores this, forcing content on people who are not developmentally ready for it, resulting in low retention.

3.1.5 Orientation to Learning

Adults are life-centered (or task-centered/problem-centered) in their orientation to learning. They are motivated to learn to the extent that they perceive that learning will help them perform tasks or deal with problems that they confront in their life situations. They want to learn “how to conduct this difficult performance review tomorrow,” not “the theoretical underpinnings of human resources management.” PD must be organized around problems, not subjects.

3.1.6 Motivation

While adults are responsive to some external motivators (better jobs, promotions, higher salaries), the most potent motivators are internal pressures (the desire for increased job satisfaction, self-esteem, quality of life). PD that focuses solely on compliance (“do this or get fired”) fails to tap into the sustainable engine of internal motivation.

3.2 Critiques of the Andragogy-Pedagogy Dichotomy

While Knowles’ framework is the bedrock of modern L&D, it is not without critics. Some scholars argue that the distinction between andragogy and pedagogy is a false dichotomy. They contend that “true pedagogy” can also be transformative and respectful of the learner, and that Knowles created a “straw man” of pedagogy to bolster his theory.

Furthermore, Knowles himself eventually modified his position, acknowledging that the two approaches represent a continuum rather than a binary. There are situations where an adult is a complete novice (e.g., learning a totally new software language) and requires directive, pedagogical instruction. Conversely, children can exhibit self-directed, andragogical traits in areas of high interest.

Despite these critiques, the core insight remains valid for professional development: experienced professionals resist directive, non-contextualized instruction. The critique serves as a reminder to be flexible—using directive methods when appropriate (e.g., safety compliance training) but shifting to facilitative methods for complex behavioral change.

3.3 Transformative Learning Theory: The Disorienting Dilemma

Jack Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory offers a deeper psychological explanation for why behavioral change is difficult. Mezirow argues that we view the world through “meaning structures“—frames of reference that filter our understanding. True professional growth requires a transformation of these frames of reference, not just the addition of new facts.

The catalyst for this transformation is the “Disorienting Dilemma“. This is an experience where the learner’s current understanding is insufficient to explain a new reality. For a teacher, this might be a video recording of their classroom showing that they talk for 80% of the lesson, contradicting their self-belief that they run a student-centered classroom.

This dilemma triggers a 10-phase process, including:

- Disorienting Dilemma: The shock of recognition.

- Self-Examination: Often accompanied by feelings of guilt or shame.

- Critical Assessment: Examining the assumptions that led to the error.

- Exploration: Looking for new roles or actions.

- Reintegration: incorporating the new perspective into one’s life.

Effective PD must safely manufacture these dilemmas. However, a dilemma without support is just trauma. The “20%” of coaching in the 70-20-10 model provides the safety necessary to navigate the “Self-Examination” and “Critical Assessment” phases. Without a coach, the learner often resolves the dilemma through denial (“The camera angle was bad,” “The students were just tired today”) rather than transformation.

4. The Coaching Paradigm: From Event to Process

4.1 The Statistical Imperative for Coaching

If the workshop is the problem, coaching is the empirically validated solution. The research of Joyce and Showers remains the gold standard for this assertion. Their data indicates that while “theory” and “demonstration” (the workshop) yield ~5-10% transfer, the addition of “peer coaching” raises transfer rates to 75-90%.

This massive jump in efficacy is due to the job-embedded nature of coaching. It moves professional development from an “event” (something that happens on Tuesday) to a “process” (something that happens continuously). Coaching addresses the “Need to Know” and “Orientation to Learning” of andragogy by dealing directly with the learner’s immediate context.

4.2 Jim Knight’s Instructional Coaching Model

Jim Knight, a prominent researcher in the field, emphasizes that the mode of coaching matters as much as the act of coaching. He advocates for a “Partnership Approach” rather than a directive approach. His research shows that teachers are four times more likely to plan to implement what they learned from a coaching conversation when the coach uses a partnership approach.

4.2.1 The Partnership Principles

Knight identifies seven principles that must govern the coaching relationship to ensure it respects adult autonomy:

- Equality: The coach and teacher are partners; the coach is not the “boss.”

- Choice: The teacher chooses the goal and the strategy.

- Voice: The conversation is open and honest.

- Reflection: The coach aids reflection rather than dictating solutions.

- Dialogue: The goal is thinking together.

- Praxis: The focus is on applying ideas to real life.

- Reciprocity: The coach learns as much as the teacher.

4.2.2 The Impact Cycle

Knight’s operational model is the “Impact Cycle,” which consists of three stages:

- Identify: The teacher gets a clear picture of reality (often through video) and identifies a student-focused goal (e.g., “increase student engagement to 90%”). They then select a teaching strategy to meet that goal.

- Learn: The coach helps the teacher learn the strategy, often through modeling or checklists.

- Improve: The teacher implements the strategy, gathers data, and the coach and teacher brainstorm adaptations until the goal is met.

This cycle is iterative and data-driven. It avoids the vagueness of general PD by focusing on a specific, measurable outcome.

4.3 Cognitive Coaching: Mediating Thinking

While Instructional Coaching often focuses on specific behaviors and strategies, Cognitive Coaching, developed by Costa and Garmston, focuses on the invisible mental processes that drive behavior. The premise is that “observable behavior is the tip of the iceberg, and the bulk of the iceberg is the thinking that produces the behavior“.

Cognitive Coaching seeks to enhance the professional’s capacity for self-directed learning by mediating their thinking. It aims to develop five “States of Mind“:

- Consciousness: Awareness of self and others.

- Efficacy: Knowing that one has the capacity to make a difference.

- Flexibility: The ability to see multiple perspectives.

- Craftsmanship: Seeking precision and refinement.

Interdependence: Knowing that we are part of a system.

In a Cognitive Coaching conversation, the coach acts as a non-judgmental mediator. They do not offer advice or solutions. Instead, they ask questions that force the coachee to clarify their own thinking, predict outcomes, and analyze results. This builds long-term capacity; the goal is for the coachee to eventually be able to “coach themselves”.

The Role of Autonomy and Self-Determination

A critical theme across all effective coaching models is the preservation of teacher autonomy. Research by Deci and Ryan on Self-Determination Theory suggests that autonomy is a fundamental psychological need. When autonomy is threatened (e.g., by a directive coach telling a teacher what to do), motivation crashes.

Knight argues that “Control leads to compliance; autonomy leads to engagement”. In a professional setting, the practitioner must be the decision-maker. The coach’s role is to provide options and evidence, but the final choice of practice must remain with the teacher. This neutralizes the “ego barrier” that often prevents leaders and teachers from accepting help; if they are in control of the process, asking for help is an act of agency, not weakness.

Virtual Coaching and the Role of AI

The scalability of coaching is often limited by the availability of qualified coaches. Technology is beginning to bridge this gap. Virtual coaching platforms allow for “ear-bug” coaching (real-time feedback via earpiece) and asynchronous video annotation, which have been shown to be effective in creating reflective relationships.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the new frontier in this domain. AI tools can now analyze audio/video of instruction to provide immediate feedback on metrics such as “talk time” ratios, question types, and “uptake” (how well a teacher builds on student ideas). While AI cannot replace the relational aspect of coaching, it can handle the low-level data gathering, allowing human coaches to focus on the high-level interpretation and strategy. This “hybrid” model offers a pathway to providing high-frequency feedback at scale, something impossible with human-only models.

Peer Learning Ecosystems: Socializing Intelligence

Communities of Practice (CoP)

Etienne Wenger’s theory of Communities of Practice (CoP) posits that learning is fundamentally a social phenomenon. A CoP is a group of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly.

Unlike a formal department or team, a CoP is defined by three elements:

- The Domain: A shared interest that gives the community its identity.

- The Community: The relationships and joint activities that build trust.

- The Practice: The shared repertoire of resources, tools, and stories.

Successful CoPs require specific “gardening” to thrive. They cannot be mandated, but they can be cultivated. Success factors include identifying a domain that energizes the core group, recruiting a skillful facilitator, and having the visible support of organizational leaders (sponsorship) without their heavy-handed interference (micromanagement). The lifecycle of a CoP often moves from potential to coalescing, to maturing, and finally to transformation, requiring different support at each stage.

Japanese Lesson Study: The Gold Standard of Peer Inquiry

Perhaps the most sophisticated model of peer learning is Japanese Lesson Study (Jugyokenkyu). This methodology is credited with the high quality of mathematics instruction in Japan and focuses on the collaborative improvement of the lesson, not the teacher.

The Lesson Study Cycle involves:

- Kyozaikenkyu: Deep study of the curriculum and materials before planning.

- Planning: Collaborative design of a “Research Lesson” by a team of teachers.

- Research Lesson: One team member teaches the lesson while others observe student thinking (not teacher behavior).

- Post-Lesson Discussion: A formal colloquium to discuss the evidence of student learning and refine the lesson.

Cultural Barriers to Implementation:

Adapting Lesson Study in the West has proven difficult due to cultural barriers.

- Privacy: Western teaching is culturally isolated (“The Egg Crate” model). Opening one’s door to critique is often viewed as a sign of weakness or a performance evaluation, whereas in Japan, it is a professional duty.

- Time: Japanese systems build in time for collaboration. Western systems often require teachers to meet after school, leading to burnout.

- The Knowledgeable Other: In Japan, a Koshi (expert) is usually invited to guide the final reflection. Western implementations often omit this, leading to “pooled ignorance” where the group reinforces existing misconceptions.

Instructional Rounds

Adapted from the medical rounds model used in teaching hospitals, Instructional Rounds is a network-based approach to improving the “instructional core” of a system.

In this model, a network of educators (principals, district leaders, teachers) visits multiple classrooms. Crucially, the protocol forbids evaluating the teacher. Instead, observers must record descriptive evidence—what they see and hear, devoid of judgment terms like “good,” “effective,” or “boring”.

The goal is to diagnose the “Problem of Practice” at the school level. If students in five different classrooms are all engaged in passive listening, the “patient” is the school culture, not the individual teachers. This shifts the burden of improvement from the individual to the system, fostering a collaborative culture of improvement.

Mentoring Modalities: Expanding the Definition

Distinguishing Mentoring from Coaching

While often conflated, mentoring and coaching serve different functions in the PD landscape.

| Feature | Coaching | Mentoring |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Performance improvement; skill acquisition (e.g., using new software). | Career development; holistic professional growth; socialization. |

| Timeframe | Short-term; finite cycles (e.g., 6 weeks). | Long-term; indefinite relationships (years). |

| Relationship | Task-oriented partnership. | Nurturing; historically hierarchical (senior-to-junior). |

| Expertise | Coach facilitates process (may not be content expert). | Mentor passes down specific wisdom/experience. |

Organizations fail when they use mentoring to solve coaching problems (e.g., “Assign him a mentor to fix his low sales numbers”) or coaching to solve mentoring problems (e.g., “Coach her on how to navigate the company politics”).

Reverse Mentoring and DEI

Reverse Mentoring flips the traditional hierarchy, pairing a junior employee (mentor) with a senior executive (mentee). This model has gained traction for two primary purposes:

- Digital Fluency: Helping senior leaders understand new technologies and social media.

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI): Giving leaders a window into the lived experience of underrepresented groups within their organization.

This model challenges the “Self-Concept” assumption of andragogy (that age equals wisdom) but, when framed correctly, can be powerful. It empowers junior employees, giving them a voice and access to leadership (sponsorship), while preventing leadership ossification.

Reciprocal and Flash Mentoring

Reciprocal Mentoring creates a balanced relationship where both parties act as mentor and mentee, trading expertise in different domains. This aligns perfectly with the andragogical principle of “Experience as a Resource,” validating that every employee, regardless of tenure, has something to teach.

Flash Mentoring addresses the time constraint barrier. These are one-time, low-commitment sessions focused on a specific knowledge transfer. While it lacks the depth of a relationship, it allows for high scalability and enables employees to “shop” for specific expertise, functioning as a human knowledge management system. It is highly effective for “Just-in-Time” learning, aligning with the “Readiness to Learn” principle.

Evaluation: Moving Beyond the “Happy Sheet”

The Failure of Level 1 Evaluation

The widespread failure to measure training transfer is partially due to an over-reliance on the Kirkpatrick Model’s “Level 1” (Reaction). Most PD evaluation consists of a post-session survey asking, “Did you enjoy the session?” or “Was the lunch good?”.

Research shows that “Level 1” satisfaction scores often correlate negatively with learning. Effective training is often difficult, challenging, and uncomfortable (the “Disorienting Dilemma”). If a trainer challenges a learner’s misconceptions, the learner may rate the session lower, despite learning more. By optimizing for “happiness,” organizations incentivize entertainment over education.

Guskey’s Critical Addition: Organizational Support

Thomas Guskey argues that the Kirkpatrick model is insufficient for professional development because it ignores the context. He proposes a five-level model, with a crucial addition: Organizational Support and Change.

Guskey argues that even if a participant learns a skill (Level 2) and wants to apply it (Level 3), they will fail if the organization actively or passively blocks them. For example, a teacher may learn a new inquiry-based science method, but if the district requires them to adhere to a rigid pacing guide that allows no time for inquiry, the training will fail.

Therefore, evaluation must measure the system as well as the learner. Questions should include: “Did the administration provide the necessary resources?” “Was time allocated for implementation?” “Did policies change to support the new practice?” Without evaluating organizational support, the failure of training is unjustly blamed on the individual.

Conclusion: The Imperative for Systemic Redesign

The evidence presented in this analysis leads to a singular, unavoidable conclusion: the “transfer of training” problem is not a mystery of human nature, but a predictable consequence of flawed organizational design. For decades, the professional development landscape has been dominated by a pedagogical, event-based model that ignores the biological and psychological realities of adult learning. The “one-off” workshop, while administratively convenient, acts as a placebo—giving the appearance of treatment while the underlying condition of stagnation remains untreated.

To bridge the Knowing-Doing Gap, organizations must fundamentally restructure their learning architecture. This requires:

- A shift from Events to Ecosystems: Moving budget and focus from “Training Days” to longitudinal coaching cycles.

- The Integration of 70-20-10: Recognizing that formal training (10%) is useless without the reflective processing provided by coaching (20%) to unlock the lessons of experience (70%).

- Respect for Andragogy: Designing learning that is problem-centered, self-directed, and respectful of the learner’s experience.

- Systemic Evaluation: Measuring organizational support and behavioral change, not just participant satisfaction.

The cost of this transition is significant, requiring investment in coaching personnel, time for peer inquiry, and technology for scaling feedback. However, the cost of the status quo—billions of dollars and millions of hours spent on training that vanishes the moment the session ends—is infinitely higher. Sustainable change is not an act of dissemination; it is an act of supported, collaborative construction.