Redefining Effective Classroom Technology for Deep Learning

Executive Summary: The Digital Paradox and the Imperative for Rigor

In the third decade of the 21st century, the educational landscape is characterized by a pervasive digital ubiquity. The “digital divide,” once defined by a lack of access to hardware, has mutated into a “digital glare”—a phenomenon where the sheer luminosity of screens and the sophistication of software interfaces often obscure the pedagogical vacuity of the activities performed upon them. Schools have invested billions in infrastructure, achieving a near-universal 1:1 student-to-device ratio in many developed nations, yet the anticipated transformation in learning outcomes remains statistically elusive. The prevailing metric for success in this digital transition has long been “engagement,” a nebulous term often conflated with behavioral compliance, visual attention, or entertainment value.

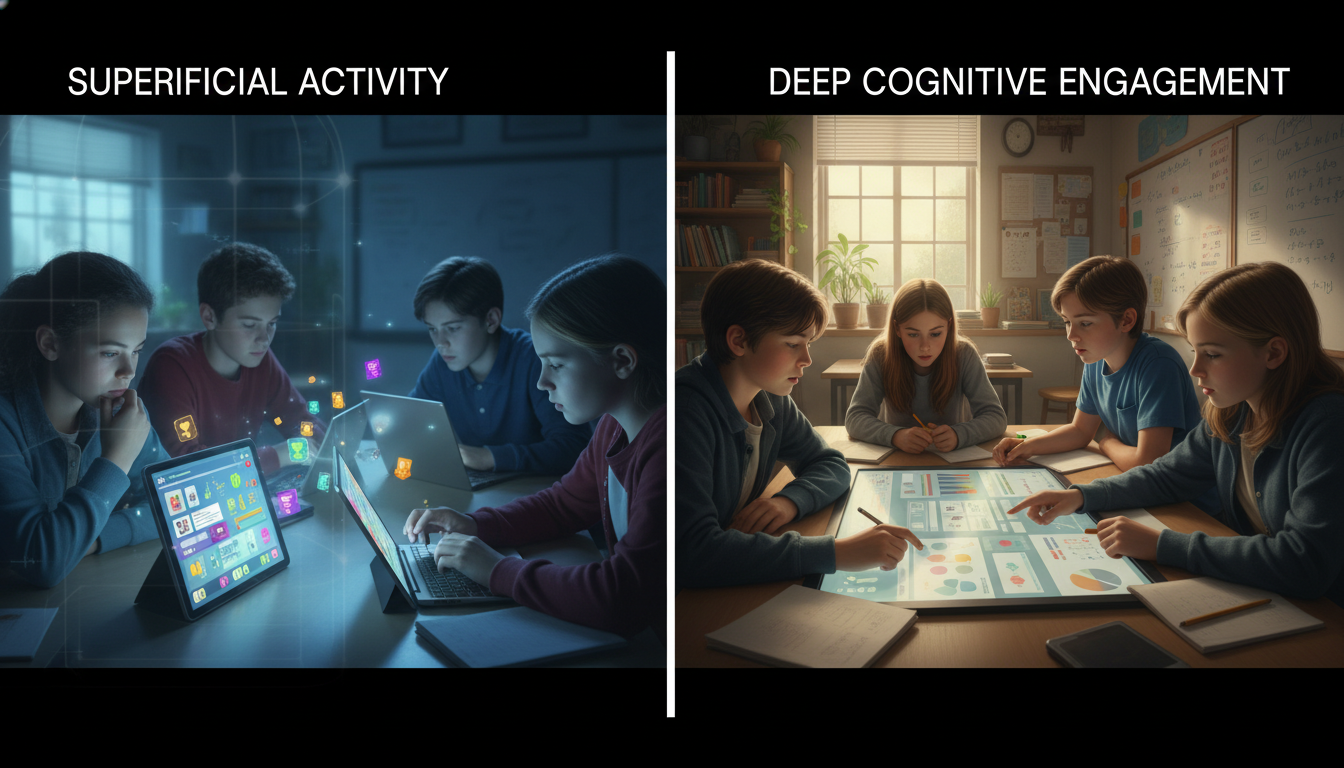

A student staring intently at a gamified quiz application, frantically tapping answers to beat a countdown timer, is deemed “engaged.” A classroom silent but for the clicking of keys is viewed as “productive.” Yet, this report argues that such metrics are fundamentally flawed. They measure the capture of attention, not the processing of information. When the digital confetti settles and the devices are powered down, retention of the material often dissipates, revealing a “screen inferiority effect” where deep comprehension is sacrificed for surface-level interaction.

This research report establishes a rigorous new standard for evaluating classroom technology, moving beyond the superficial metrics of behavioral engagement to the substantive domains of cognitive activation, constructive participation, and deep conceptual understanding. Drawing upon a synthesis of the Learning Sciences—specifically Cognitive Load Theory, the ICAP framework (Interactive, Constructive, Active, Passive), and John Hattie’s Visible Learning meta-analyses—we posit that effective technology is not defined by user interface appeal or student enthusiasm, but by its ability to facilitate high-order thinking processes that could not be achieved through analog means.

The analysis presented herein reveals a stark dichotomy in the data. While generic “web-based learning” yields a negligible effect size (d=0.18), specific, pedagogically sound interventions such as Intelligent Tutoring Systems (d=0.48) and Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (d=0.52) show promise when aligned with rigorous instructional design. Conversely, the uncritical adoption of devices has been linked to negative correlations in reading comprehension and a degradation of note-taking efficacy due to the loss of haptic cognitive encoding.

To reclaim the promise of educational technology and build professional authority, educators must transition from being “dopamine dispensers” to “cognitive architects.” This requires a shift from using technology to Engage attention to using it to Enhance and Extend learning capabilities. This report provides the theoretical underpinning, the empirical evidence, and the practical diagnostic protocols necessary to navigate this shift, empowering educators to defend their pedagogical choices with the weight of scientific consensus.

Part I: The Engagement Trap and the Illusion of Competence

The fundamental error in the implementation of educational technology over the last two decades has been the conflation of distinct types of engagement. In the rush to modernize classrooms and “meet students where they are,” the educational sector has allowed “engagement” to become a catch-all proxy for learning. However, this simplification ignores the complex multidimensionality of student involvement. Research broadly distinguishes between three distinct dimensions: behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement. Understanding the interplay—and often the friction—between these dimensions is critical to redefining effectiveness.

1.1 Deconstructing “Engagement”: Behavioral vs. Cognitive

Behavioral Engagement refers to the observable actions of the student: adherence to classroom rules, physical presence in the digital environment, and the completion of assigned tasks. In a technological context, this is the metric most easily captured by learning management systems and dashboard analytics. A student swiping through a flashcard app is behaviorally engaged. They are “on task.” Their “time on site” is high. Yet, this metric fails to capture whether the student is mentally processing the information or merely operating the interface. It is entirely possible for a student to be behaviorally compliant—clicking the right buttons at the right time—while their mind is entirely disengaged from the underlying concepts. This is the phenomenon of the “active user” who is a “passive learner.”

Emotional Engagement involves the student’s affective reaction to the learning environment: their interest, enjoyment, and sense of belonging. Educational technology excels in this domain. Developers utilize gamification mechanics—bright colors, immediate auditory feedback, badges, and progress bars—to generate excitement and reduce the perceived effort of learning. While emotional safety and interest are prerequisites for learning, high emotional engagement does not guarantee cognitive processing. In fact, the “seductive details” of an educational app—animations, sound effects, and game narratives—can act as extraneous load, consuming working memory resources that should be dedicated to the schema acquisition. This results in students who enjoy the experience of the class but fail to retain the content of the lesson.

Cognitive Engagement, the true gold standard for effective technology, is defined by the student’s psychological investment in the learning process. It involves the use of deep processing strategies, self-regulation, and the willingness to exert mental effort to understand complex ideas. Cognitively engaged students do not just answer questions; they ask them. They connect new information to prior knowledge, monitor their own understanding (metacognition), and persist through difficulty not because of a digital reward, but because of a drive for mastery.

The “Engagement Trap” occurs when technology successfully drives behavioral and emotional engagement but fails to trigger—or actively suppresses—cognitive engagement. A student playing a competitive math game may be screaming with excitement (High Emotional) and tapping furiously (High Behavioral), but if they are merely pattern-matching answers to gain points without calculating the underlying problems, cognitive engagement is effectively zero.

1.2 The “Chocolate-Covered Broccoli” Phenomenon

The trap is most visible in what educational theorists often term the “chocolate-covered broccoli” approach to edtech: the practice of taking dry, rote, or poorly designed content and coating it in a layer of gamification points, badges, and leaderboards. This approach is rooted in behaviorism, relying on extrinsic motivation to drive performance.

Research indicates that while this may temporarily boost compliance and time-on-task, it often undermines long-term motivation. When the digital rewards (the chocolate) are removed, the motivation to engage with the content (the broccoli) evaporates, often leaving the student with less intrinsic interest than before. Furthermore, gamified environments often prioritize speed over depth. In speed-based quiz games, the pressure to answer quickly discourages the “slow thinking” required for deep conceptual retrieval. Students learn to employ heuristic strategies—guessing based on answer length, recognizing surface cues, or memorizing specific question strings—rather than engaging in genuine retrieval practice.

The dopamine hit of a “correct” ding becomes the pedagogical goal, rather than the restructuring of long-term memory. This creates an “illusion of competence.” The student feels successful because they are accumulating points, and the teacher feels successful because the class is lively and “engaged,” but the actual transfer of knowledge to long-term memory is minimal. The technology has masked the lack of learning with the veneer of activity.

1.3 Anatomy of Failure: The LAUSD iPad Initiative

To understand the catastrophic consequences of prioritizing devices over pedagogy, one must examine the 2013 Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) iPad initiative. This $1.3 billion project, one of the most ambitious edtech rollouts in history, aimed to provide every student with a device, driven by a vision of closing the digital divide and “transforming” learning. It serves as a definitive case study in how “engagement” metrics can lead to systemic failure.

The initiative was plagued by “technocentrism”—the belief that the mere presence of technology causes learning.

- Lack of Pedagogical Vision: The rollout was treated primarily as a hardware deployment logistics challenge rather than a curriculum redesign. Teachers were given devices without a clear framework for how these tools would improve cognitive engagement or alter instruction. The assumption was that the device itself was the change agent.

- The Hacking of “Engagement”: Within days of the rollout, students—who were behaviorally engaged with the devices but cognitively under-stimulated by the restrictive Pearson content pre-loaded onto them—bypassed security filters. They accessed social media, games, and unauthorized websites. This was not merely an act of rebellion; it was a rational response to a tool that was presented as a portal to the world but locked down to deliver static worksheets.

The students demonstrated high technical literacy (hacking the profiles) but applied it to escape the educational content rather than engage with it.

The “Spray and Pray” Strategy

The district employed what critics called a “spray and pray” strategy: showering schools with devices and hoping for a corresponding academic benefit. The lesson learned, as noted by researchers analyzing the failure, is that “digital content delivery is still content delivery”. A worksheet displayed on a retina screen is still a worksheet, but now it carries the added cognitive load of the device’s interface and the perpetual potential for distraction.

The LAUSD case demonstrates that when technology is introduced without a rigorous definition of “effective use”—one that demands cognitive rather than just behavioral participation—it becomes a distraction engine rather than a learning accelerator. It failed because it focused on the access to technology rather than the cognition supported by it.

1.4 The Economics of Attention: Dopamine vs. Deep Work

The modern “engagement trap” is exacerbated by the “attention economy” that underpins the design of modern software. Educational tools are often built by developers who borrow design patterns from social media and mobile gaming—infinite scroll, variable reward schedules (slot machine mechanics), and flashy, immediate notifications.

Teachers report feeling an immense pressure to become “dopamine dispensers,” competing with highly optimized entertainment platforms for student attention. This creates a dangerous feedback loop in the classroom. If a lesson is “boring”—which is to say, if it requires sustained, quiet, difficult mental effort—it is perceived as a failure of the teacher to be sufficiently “engaging.”

However, deep learning is inherently difficult. It involves what Bjork terms “desirable difficulties”—struggles that trigger the encoding processes necessary for long-term memory. By using technology to smooth over every friction point and entertain at all costs, educators may be depriving students of the very cognitive struggle necessary for mastery. The “gamification of learning” risks training students to expect a digital confetti explosion for every minor success, rendering them ill-equipped for the “real world,” which, as critics note, “doesn’t award you glowing digital tokens for doing your job well”.

To build authority, the “Effective Classroom Technology” model must reject the premise that learning must always be fun. Instead, it must assert that learning must be meaningful, active, and cognitively demanding.

Part II: The Science of Learning in a Digital Context

To redefine effective technology, we must ground our metrics not in marketing claims or anecdotal enthusiasm, but in the empirical realities of how the human brain processes information. The evidence from the Learning Sciences, specifically regarding cognitive load, reading comprehension, and haptic encoding, provides a sobering counter-narrative to the glossy marketing of edtech.

2.1 Cognitive Load Theory and Multimedia Principles

At the heart of learning science is Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), which posits that human working memory is extremely limited in capacity and duration. Learning occurs when information is successfully processed in working memory and transferred to long-term memory schemas. Technology can either facilitate this process or, more commonly, disrupt it.

Richard Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning extends CLT to the digital realm, identifying that the brain has two separate channels for processing information: the visual/pictorial channel and the auditory/verbal channel. Both have finite limits.

The Coherence Principle: The Cost of “Bells and Whistles”

One of the most violated principles in edtech is the Coherence Principle, which states that people learn better when extraneous words, pictures, and sounds are excluded rather than included. Research consistently shows that adding “interesting” but irrelevant material—such as background music, decorative animations, or “fun” facts unrelated to the core concept—hurts learning. These “seductive details” consume cognitive resources that should be dedicated to processing the essential material.

A “highly engaging” app that features a dancing avatar and sound effects for every button press is, by definition, increasing extraneous cognitive load. While it captures attention (emotional engagement), it reduces the capacity available for understanding the content (cognitive engagement). Effective technology is therefore minimalist. It directs attention to the concept, not away from it. A “boring” looking interface that allows for focused manipulation of a variable is often superior to a “rich” interface cluttered with rewards.

The Split-Attention Effect

Another common failure mode is the Split-Attention Effect. This occurs when learners are required to split their attention between at least two sources of information that have been separated either spatially or temporally. For example, a digital textbook that places a diagram on one part of the screen and the explanatory text on another, forcing the student to scroll back and forth, creates a heavy cognitive tax. The mental effort used to integrate these disparate sources is unavailable for understanding the material itself. Effective technology integrates these sources, placing labels directly on diagrams or synchronizing audio narration perfectly with visual animations.

2.2 The Screen Inferiority Effect: Reading on Glass vs. Paper

A critical component of the “digital glare” is the physical medium of input and reading. As schools transition to digital textbooks, it is imperative to analyze the impact on deep reading comprehension.

Meta-analyses spanning from 2018 through 2024 consistently reveal a “screen inferiority effect” for reading comprehension, particularly with expository, informational texts. Across dozens of studies and thousands of students, those who read on paper consistently score higher on comprehension tests than those who read the same material on screens.

The mechanisms for this are multifaceted:

-

Metacognitive Regulation: Readers tend to overestimate their comprehension when reading on screens. The speed and ease of scrolling create an illusion of fluency, leading students to skim rather than read deeply. This “F-shaped” reading pattern—scanning the top and left side of the text—is prevalent in digital environments.

-

Spatial Cues: Physical paper provides fixed spatial cues (e.g., “I remember that fact was on the bottom left of the page about halfway through the book”). These cues aid in the formation of a mental map of the text, which supports memory retrieval. Scrolling text destroys these spatial landmarks, unmooring the reader.

-

Distraction Potential: The device used for reading is often the same device used for social interaction and entertainment. The mere presence of the device activates the neural pathways associated with rapid task-switching, reducing the sustained attention required for deep reading.

Implication: “Effective” technology usage sometimes means putting the device away. A hybrid approach, where students read complex texts on paper to build deep schema and then use technology to analyze or manipulate that information, is scientifically superior to a purely paperless workflow.

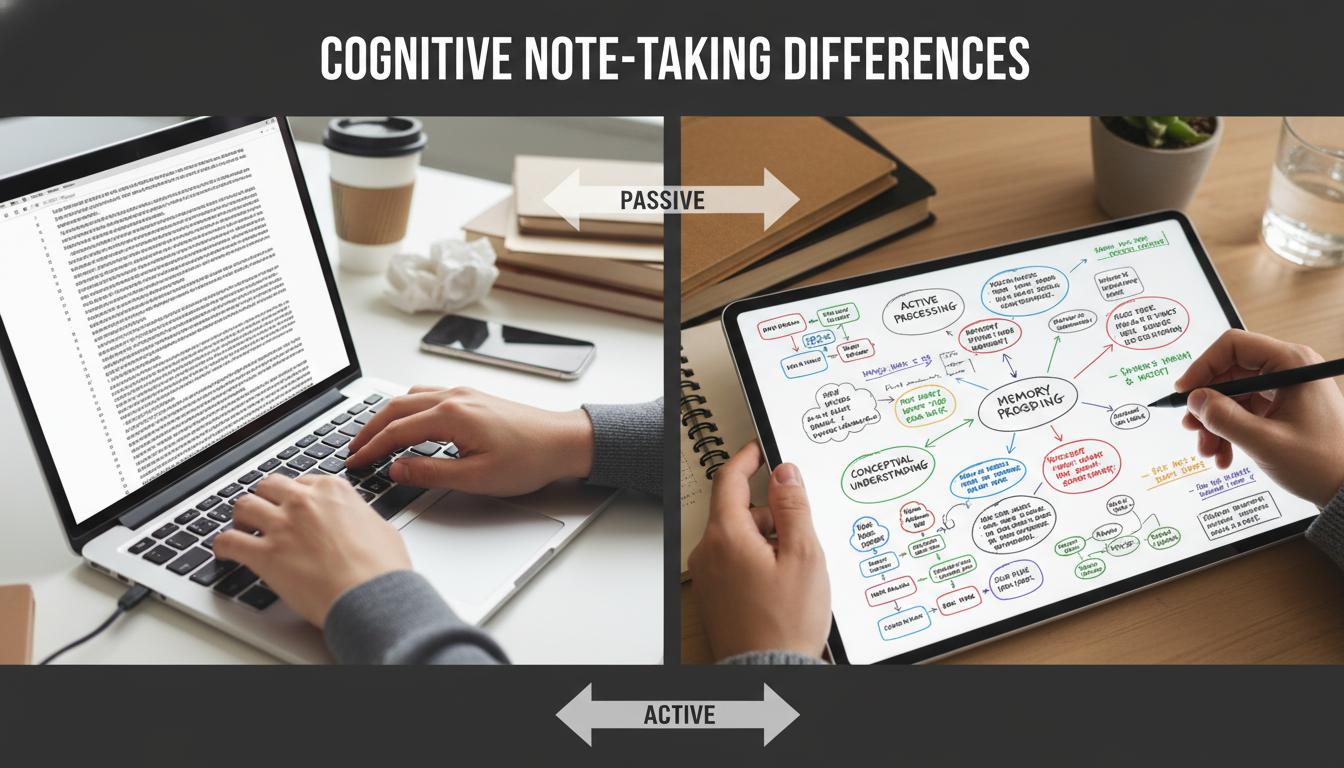

2.3 The Neuroscience of Note-Taking: The Stylus is Mightier than the Keyboard

The debate between handwriting (analog or digital stylus) and typing is settled by recent neuroscience. While typing is often faster and allows for the capture of more content (verbatim), it is less effective for conceptual understanding.

High-density EEG studies replicate findings that handwriting triggers widespread brain connectivity in parietal and central regions crucial for memory formation and the encoding of new information. Typing on a keyboard does not elicit these same connectivity patterns. The complex motor planning involved in forming letters and the tactile feedback of the pen contribute to the “haptic bond” with the information.

Furthermore, the Generative Processing hypothesis suggests that because typing is fast, students tend to transcribe lectures verbatim, acting as passive conduits for information. Because handwriting is slower, the student is forced to process, summarize, and rephrase the information in real-time to keep up. This act of synthesis—a Constructive activity in the ICAP framework—leads to deeper conceptual understanding.

Conclusion: Technology that replaces handwriting with typing for the purpose of note-taking is often a step backward in cognitive efficacy. However, technology that utilizes a digital stylus (tablet writing) can bridge this gap, maintaining the cognitive benefits of handwriting while offering the organizational benefits of digital storage.

Part III: Visible Learning and the Evidence Base

To rebuild authority in the classroom, educators must replace the vague goal of “tech integration” with rigorous evidence regarding “what works.” John Hattie’s Visible Learning research, a synthesis of over 1,400 meta-analyses involving millions of students, provides the most comprehensive data set for evaluating educational interventions.

3.1 The Hattie Effect Sizes: The Data on Digital Efficacy

Hattie establishes a “hinge point” of $d=0.40$ as the average effect size for educational interventions. An effect size of 0.40 represents one year of growth for one year of school. Interventions below this threshold are of negligible impact compared to the natural maturation of the student and the passage of time.

The data on technology is revealingly mediocre when viewed in isolation.

It suggests that the mere presence of technology is not a driver of achievement.

| Intervention | Effect Size | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Technology in Distance Education | 0.01 | Negligible / No Impact |

| One-on-One Laptops | 0.16 | Low Impact (Below Average) |

| Web-Based Learning | 0.18 | Low Impact (Below Average) |

| Audiovisual Methods | 0.22 | Low Impact (Below Average) |

| Programmed Instruction | 0.23 | Low Impact (Below Average) |

| Technology in Mathematics | 0.33 | Moderate Impact |

| Intelligent Tutoring Systems | 0.48 | High Impact (Above Average) |

| Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning | 0.52 | High Impact (Above Average) |

| Interactive Video Methods | 0.54 | High Impact (Above Average) |

| Teacher Credibility (Non-Tech) | 0.90 | Very High Impact |

3.2 The Pedagogy of the Method, Not the Medium

The disparity between “Web-based learning” ($d=0.18$) and “Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning” ($d=0.52$) confirms a critical insight: The medium is less important than the method. Technology acts as an amplifier of pedagogy.

- If the pedagogy is “passive consumption” (e.g., watching a video, reading a PDF), technology amplifies the passivity by introducing the potential for distraction. This explains the low score for audiovisual methods and web-based learning.

- If the pedagogy is “active collaboration” or “adaptive feedback,” technology amplifies the reach and speed of that interaction.

Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS) ($d=0.48$) succeed because they mimic the “feedback loop” of a human tutor. They provide immediate, corrective information and adapt the difficulty of the task to the learner’s proficiency, keeping them in the Zone of Proximal Development. This stands in stark contrast to “Programmed Instruction” ($d=0.23$), which is often linear and non-adaptive.

Interactive Video Methods ($d=0.54$) succeed because they transform a passive medium into an active one. Tools that require a student to answer a prediction question before the video continues, or to click on parts of the screen to identify variables, force cognitive engagement. The video becomes a tool for inquiry rather than a broadcast for consumption.

3.3 The Role of Feedback in Technology

One of the most powerful influences on achievement is Feedback ($d=0.70$). However, technology’s record on feedback is mixed. Automated feedback can be highly effective if it is elaborative—explaining why an answer is wrong—rather than just verifying correctness (Result-Knowledge).

A meta-analysis of digital monitoring tools found that while simply showing teachers a dashboard of student data has a moderate effect ($d=0.12$), systems that provided instructional advice based on that data or offered specific breakdowns of student misconceptions had significantly higher impacts.

Insight: For technology to be effective, it must close the feedback loop. “Data-driven” classrooms where data is collected but not acted upon immediately are examples of “Data Rich, Information Poor” environments. Effective technology processes data to give the teacher or student an immediate “next step.”

Part IV: Frameworks for Rigor and Authority

To move beyond the vague goal of “tech integration” and build professional authority, educators must adopt rigorous frameworks that allow them to measure and articulate the learning value of their digital choices. Two frameworks stand out for their alignment with the science of learning: the ICAP Framework and the Triple E Framework.

4.1 The ICAP Framework: A Rubric for Cognitive Depth

Developed by cognitive scientist Michelene Chi, the ICAP Framework categorizes learning activities based on overt behaviors that predict cognitive depth and learning outcomes. It provides a hierarchical rubric for evaluating what students are doing with technology.

The hypothesis, strongly supported by empirical evidence, is that learning outcomes improve as one moves up the hierarchy: Interactive > Constructive > Active > Passive.

| Mode | Definition | Cognitive Process | Low-Efficacy Tech Example | High-Efficacy Tech Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive | Receiving information without overt action. | Storing (Isolated) | Watching a YouTube video without pausing; Reading a digital text. | N/A (Technology used purely for delivery). |

| Active | Manipulating content physically to emphasize attention. | Integrating (Activating) | Highlighting text in an e-book; Rewinding a video; Clicking “next” in a slideshow. | Virtual manipulatives in math; Drag-and-drop categorization tasks. |

| Constructive | Generating new outputs beyond the information given. | Inferring (Deriving) | Copy-pasting notes into a doc. | Creating a digital concept map; Coding a simulation; Writing a blog post reflection; Recording a “Think Aloud” video. |

| Interactive | Co-creating with a partner; dialogic exchange. | Co-inferring (Synergizing) | Posting a generic comment (“Good job”) on a discussion board. | Debating via threaded video (Flipgrid); Co-editing a Google Doc in real-time with required commenting; Peer-reviewing code. |

The Tech Failure Mode: Most commercial edtech is designed for the Passive or Active levels. “Personalized learning” playlists often consist of Passive video watching followed by Active multiple-choice clicking. While this keeps students busy, it rarely triggers the Constructive processes of synthesis and generation.

The Authority Shift: A teacher using ICAP can look at a lesson where students are “watching a documentary” on their iPads and identify it as Passive. By requiring students to “pause every 5 minutes and write a prediction in the chat” (Constructive/Interactive), the teacher fundamentally alters the cognitive efficacy of the lesson without changing the content.

4.2 The Triple E Framework: Engagement, Enhancement, Extension

Developed by Liz Kolb, the Triple E Framework directly addresses the “engagement trap” by treating engagement as merely the entry point, not the destination. It forces the educator to ask three critical questions.

- Engagement (Time-on-Task): Does the tool help the student focus on the learning goals? Or does it distract?

- Failure: Students spend 20 minutes choosing a font or an avatar for a 5-minute presentation. This is time-off-task disguised as work.

- Success: The software creates an immersive environment (e.g., a VR historical site) that rivets attention specifically to the historical details.

- Enhancement (Value-Added): Does the tool aid the student in developing a more sophisticated understanding than they could without it? This refers to scaffolding.

- Failure: Using a digital whiteboard to write a math problem exactly as one would on paper. This is replacement, not enhancement.

- Success: Using a dynamic graphing calculator (e.g., Desmos) to visualize the change in slope instantaneously as a variable changes. This allows the student to see the relationship between the equation and the line in a way that static drawing cannot replicate.

- Extension (Transfer): Does the tool create a bridge between school learning and everyday life? Does it allow learning to continue outside the school day?

- Success: Students using digital tools to connect with experts via Zoom, or publishing their writing to a real-world audience via a blog, bridging the gap between “school work” and “real work”.

The Scoring Protocol: When a teacher evaluates a lesson using Triple E, they might find a “Red Light” result for a popular app like a generic math game (High Engagement, Low Enhancement, Low Extension). This empowers the teacher to reject the tool despite its popularity, grounding their decision in learning science.

4.3 Moving from Engagement to Empowerment

A final, crucial conceptual shift is articulated by John Spencer: the move from Student Engagement to Student Empowerment.

- Engagement is often compliance with a smile. The teacher does the work of designing the “fun,” and the student consumes it.

- Empowerment is student ownership. The student selects the tools, sets the goals, and assesses the quality of the work.

In an empowered technology classroom, the student is not a consumer of apps but a creator of artifacts. They do not just “do the module“; they “curate the resources,” “produce the tutorial,” or “design the simulation.” This shifts the cognitive load from the teacher (who is juggling entertainment) to the student (who is juggling complexity).

Part V: High-Yield Technological Pedagogies

Having established the theoretical “what not to do” and the frameworks for evaluation, we turn to evidence-based strategies where technology creates verifiable value. These strategies leverage the Constructive and Interactive modes of ICAP and align with high effect-size influences from Hattie’s research.

5.1 Digital Concept Mapping: Visualizing Complexity

Effect Size: $d=0.66$.

Concept mapping is a strategy where students visually organize knowledge, connecting concepts with labeled arrows to show relationships. While paper maps are effective, digital tools (e.g., Lucidchart, Miro, MindMup) offer Enhancement capabilities that paper cannot match: infinite canvas size, easy restructuring of nodes without erasing, and the embedding of multimedia evidence within nodes.

- Why it works: It is a quintessentially Constructive activity. Students must make executive decisions about the hierarchy of ideas and the nature of the relationships (causality, association, part-whole).

- The Upgrade: Using a “fill-in-the-map” approach with immediate automated feedback can guide students who are novices. This provides a scaffold that reduces the intrinsic load of starting from a blank page while still demanding relational thinking.

Research shows this structured approach yields high effect sizes particularly for students with lower prior knowledge.

Generative AI as a Socratic Tutor

Emerging Research Field.

The integration of Generative AI (GenAI) presents a unique opportunity to scale Interactive learning. Standard chatbots often act as “answer engines,” promoting passivity and academic dishonesty. However, when prompted to act as a Socratic Tutor, GenAI can significantly enhance critical thinking.

- Mechanism: Instead of providing the answer, the AI asks guiding questions, forcing the student to articulate their reasoning. This mimics the “Interactive” mode of ICAP (dialogue) and the “One-on-One Tutoring” effect.

- Evidence: Studies indicate that Socratic tutoring by AI supports the development of reflection and critical thinking better than standard interactions. It reduces the “prior knowledge gap” by providing just-in-time scaffolding, allowing students to engage with higher-order concepts they might otherwise fail to grasp.

- Implementation: The teacher must act as the “Prompt Engineer,” designing the system instructions to ensure the AI facilitates Productive Failure—allowing the student to struggle and guiding them out of misconceptions without simply correcting them.

Metacognition via Asynchronous Video (Flipgrid)

Focus: Reflection and Self-Regulation.

Tools like Flipgrid (now Microsoft Flip) are often used for social engagement (“Say hi to the class!”). To be effective, they must be repurposed for metacognition.

- Strategy: “Think Aloud” protocols. Students record themselves solving a math problem, analyzing a text, or debugging code, explicitly verbalizing their thought process as they work.

- Value: This converts a solitary task into a Constructive one. The act of explaining reinforces the neural pathways—a phenomenon known as the “Protégé Effect” (teaching others helps the teacher learn).

- Feedback: It allows the teacher to hear the process, not just see the product (the answer), enabling targeted intervention on misconceptions that would otherwise be invisible in a written assignment.

Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL)

Effect Size: $d=0.52$.

CSCL is not just “group work” on a computer. It is the use of technology to create positive interdependence, where students must work together to succeed.

- The Jigsaw Method 2.0: Students in different physical locations (or groups) access different digital datasets. They must collaborate via a shared digital workspace (like a shared Google Sheet or a collaborative whiteboard) to solve a complex problem that requires all pieces of data.

- Impact: This forces Interactive engagement. The technology mediates the complexity of the data sharing, allowing the students to focus on the synthesis and negotiation of meaning. Meta-analyses show this has moderate-to-large effects on both achievement and social interaction, largely because it distributes the cognitive load across the group.

The Teacher-Researcher and Professional Authority

The final step in redefining effective technology is a shift in professional identity. Teachers must stop viewing themselves as consumers of edtech products and start viewing themselves as researchers of their own classrooms. This stance, the “Teacher-Researcher,” builds professional authority and insulates the educator from fads.

Diagnostic Protocols: Analyzing the Failed Lesson

When a high-tech lesson results in high engagement but low learning (the “failed lesson” scenario), the teacher-researcher does not abandon tech but analyzes the failure. Use this diagnostic heuristic.

| Diagnostic Question | Indicator of Failure | Correction Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Was the Cognitive Load Intrinsic or Extraneous? | Students asked “How do I use this button?” more than “Why does this reaction happen?” | Simplify Interface: Use the tool for a simpler task first, or switch to analog for the concept introduction until the tech is mastered. |

| What was the ICAP Mode? | Students were swiping, clicking, or watching (Passive/Active). | Upgrade Mode: Require a generated output (Constructive) or a peer debate (Interactive) before the tech interaction concludes. |

| Did the Tech Mask Incompetence? | Students got 100% on the quiz by guessing or pattern matching. | Change Assessment: Ask for a written justification of one “correct” answer. If they can’t do it, the tech failed to teach. |

| Was it “Chocolate-Covered Broccoli”? | Students stopped working the moment the “points” or “badges” stopped. | Reframe: Focus on the intrinsic value of the problem. Use tech for visualization, not gamification. |

Observational Rubric for Cognitive Engagement

School leaders and teachers can use this abbreviated rubric (based on Triple E and ICAP) to observe and evaluate classroom tech use. This creates a data-driven conversation about practice.

Score (0-2 for each):

- 1. Focus (Behavioral): Does the student screen show the learning target, or are they navigating menus/multitasking? (0=Distracted, 1=Passive Compliance, 2=Target Focused)

- 2. Generative Processing (Cognitive): Is the student producing information (writing, coding, speaking) or consuming it? (0=Consuming, 2=Producing)

- 3. Co-Use (Interactive): Are students using the device alone or using it as a shared reference point for conversation? (0=Isolated, 2=Social/Shared)

- 4. Value-Add (Enhancement): Could this be done on paper with the same result? (0=Yes, 2=No, tech makes the impossible possible).

Interpretation: A lesson that scores high on Focus (Behavioral) but low on Generative Processing (Cognitive) is a candidate for the “Engagement Trap.”

Communicating the Science to Parents

Parents often hold binary views on technology: they either equate “tablets in hands” with “modern education” or fear “too much screen time.” Building authority requires articulating the why behind the tech choices. The teacher-researcher defends their practice not with “the district bought these,” but with learning science.

- The Narrative: “We use technology not to entertain, but to power thinking that can’t happen on paper.”

- Transparency: When sending home digital work, include a “Parent Guide to Inquiry” that explains why the student is using a specific simulation and what questions the parent can ask (e.g., “What happens if you change this variable?”).

- Defending Analog: When parents ask why a student is hand-writing notes or reading a paper book in a “high-tech” school, cite the neuroscientific evidence on connectivity and memory. This positions the teacher not as a Luddite, but as a neuro-informed expert who uses the right tool for the right cognitive job.

The Cognitive Architect

The definition of “Effective Classroom Technology” must undergo a radical revision. It is not defined by the ratio of devices to students, the brightness of the screens, or the volume of the cheers during a gamified quiz. These are metrics of the attention economy, not the knowledge economy.

True effectiveness is defined by:

- 1. Cognitive Residue: What is left in the student’s mind when the device is turned off?

- 2. The Shift from Consumption to Construction: Does the tool allow the student to build knowledge, or merely receive it?

- 3. The Amplification of Interaction: Does the technology bring students closer to the content and to each other, or does it isolate them in a digital silo?

The research is clear: Technology is a tool of immense power, but it is neutral. It amplifies the pedagogy it serves. When coupled with “Passive” or “Active” pedagogies, it amplifies distraction and shallow processing (The Screen Inferiority Effect). When coupled with “Constructive” and “Interactive” pedagogies (ITS, CSCL, GenAI Tutoring), it amplifies human cognition.

For the educator, the path to authority lies in rejecting the role of the entertainer. We must stop juggling “chainsaws on fire” to keep attention and start building the scaffolds that allow students to climb. We must be willing to be “boring” if boring means focused, deep, and cognitively rigorous. In the end, the most high-tech device in the classroom remains the biologically evolved human brain; effective technology is simply the instrument that helps it do its best work.