EdTech’s Cognitive Paradox: Preventing Learning Failures

Introduction: The Dualistic Nature of Digital Learning

The integration of digital technology into global education systems was predicated on a promise of democratization, personalization, and efficiency. From the early adoption of Learning Management Systems (LMS) to the recent proliferation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and adaptive tutoring platforms, the overarching narrative has been one of enhancement. However, a rigorous and exhaustive examination of the empirical literature reveals a complex, dualistic reality. While technology offers unprecedented access to information and novel modalities for engagement, it frequently acts as a profound disruptor of the cognitive processes required for deep learning. This report investigates the specific mechanisms by which technology can impede learning—focusing on cognitive overload, shallow processing, and the reinforcement of misconceptions—and delineates the data-driven “early warning systems” that allow educators to detect these failures before they become entrenched.

The central thesis of this analysis is that “engagement” in the digital realm is often a false proxy for learning. High interaction rates, click-throughs, and time-on-task can mask underlying cognitive dysfunction, including “gaming the system,” “wheel-spinning,” and “mindless clicking.” Furthermore, the architectural decisions made by software developers—often borrowing from the “addiction economy” of social media and gambling—can create learning environments that are actively hostile to the sustained attention required for schema construction. By synthesizing findings from Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), educational neuroscience, and behavioral analytics, we can construct a rigorous auditing framework to distinguish between productive digital tools and those that merely tax the learner’s limited cognitive resources.

The Cognitive Cost of Digital Learning: Architecture and Overload

The human brain is not an infinite vessel for information; it is a biological system defined by severe bottlenecks, the most critical of which is working memory. Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), originating from the seminal work of Sweller and colleagues, provides the essential framework for understanding why educational technology often fails. In the context of digital learning, the primary risk is not that the material is too difficult (intrinsic load), but that the delivery mechanism itself imposes an unmanageable burden (extraneous load), leaving insufficient capacity for the actual processing of knowledge (germane load).

The Redundancy and Split-Attention Effects

Digital learning environments frequently default to a “more is better” aesthetic, layering text, audio, animation, and interactive elements in a bid to maintain user attention. However, research consistently identifies this maximalist approach as a primary driver of instructional failure through the “redundancy effect”. When learners are required to process redundant information—such as reading on-screen text while simultaneously listening to a verbatim narration of that same text—working memory is overburdened. The learner is forced to cross-reference and reconcile these two identical inputs rather than processing the underlying concept. Sweller notes that while intuition suggests providing additional information is harmless, redundancy is, in fact, “anything but harmless” and can be a major cause of instructional failure.

Closely related is the “split-attention effect,” which occurs when learners must mentally integrate disparate sources of information that are separated spatially or temporally. In poorly designed educational software, a student might be required to toggle between a simulation window and a separate worksheet, or look at a diagram on one side of the screen while reading an explanation on the other. The cognitive effort expended to “search and match” these elements is extraneous load—effort that does not contribute to learning and subtracts from the capacity available for schema construction. This creates a scenario where the difficulty of the tool artificially inflates the difficulty of the task.

The Interactivity Paradox

Interactive media is often touted as superior to passive media, yet it introduces the “interactivity paradox”. Users frequently report higher satisfaction and enjoyment with interactive news sites or non-linear learning modules compared to static text. However, the act of navigating—deciding which link to click, determining the sequence of information, and manipulating the interface—imposes a “navigational load.” This decision-making process consumes cognitive resources. As a result, while users may feel more engaged, objective measures often show that they retain less information and experience higher levels of disorientation compared to those consuming linear, “passive” content. The freedom to explore becomes a burden of administration; the learner must become the architect of their own instruction in real-time, a task for which novices are ill-equipped.

Measuring Cognitive Load: From Subjective Scales to Neurophysiology

Determining when a student is experiencing cognitive overload is a complex challenge. Traditional methods have relied on subjective rating scales, such as the nine-point Likert scale (e.g., “How difficult was this task?”), or visual analogue scales. However, recent advancements in educational neuroscience have begun to employ more objective, physiological measures.

Studies utilizing Electroencephalography (EEG) and Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) have provided direct evidence of the burden imposed by poorly designed technology. These tools can measure the neurophysiological correlates of mental effort and stress in real-time. For instance, increased activation in the prefrontal cortex, as measured by fNIRS, correlates with higher working memory load. The integration of these biometric signals into “Cognitive Load-Aware Modulation” (CLAM) systems represents the frontier of adaptive learning, where an AI system could theoretically detect cognitive overload via a webcam or wearable device and dynamically simplify the instructional material to prevent burnout. This transition from self-report to biometric monitoring highlights the severity of the issue: cognitive overload is not merely a feeling of confusion; it is a measurable physiological state that inhibits neural plasticity.

The Medium and the Mind: Screen Inferiority and the Shallowing Hypothesis

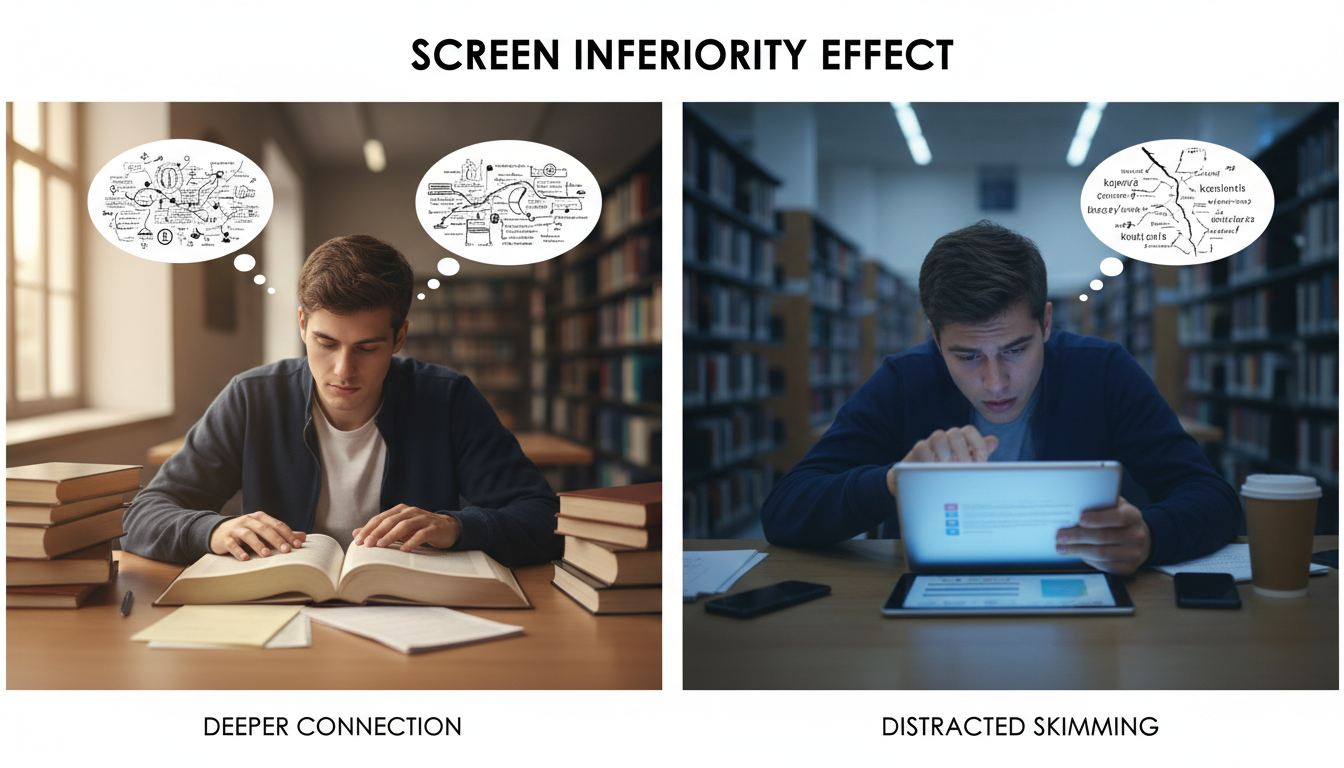

The physical medium through which learning occurs—paper versus screen, pen versus keyboard—profoundly influences the depth of cognitive processing. Despite the ubiquity of devices in classrooms, the “screen inferiority effect” remains a robust and persistent finding in educational research.

The Screen Inferiority Effect

A 2024 meta-analysis of 49 studies confirmed that students reading on paper consistently score higher on comprehension tests than those reading identical material on screens. Crucially, this effect has not diminished as “digital native” generations have entered school; in fact, the screen inferiority effect increased between 2000 and 2017. This counters the popular assumption that familiarity with technology equates to reading proficiency on it.

The mechanisms driving this inferiority are multifaceted:

- Metacognitive Calibration: Readers on screens tend to overestimate their comprehension, leading to insufficient regulation of their reading pace and effort. They skim rapidly, believing they have understood the text, whereas paper readers are more likely to pause and re-read when confused.

- Spatio-Temporal Mapping: Physical books provide spatial cues—the thickness of the pages remaining, the location of a paragraph on the top-left of a distinct page—that help the brain construct a “cognitive map” of the text. Scrolling destroys these spatial landmarks, making it harder for the reader to mentally organize the sequence of ideas.

The Shallowing Hypothesis

The “Shallowing Hypothesis” suggests that the habits associated with digital media—rapid switching, multitasking, and scanning—are bleeding over into general cognitive habits, reducing the capacity for deep, sustained attention. Frequent use of digital devices for entertainment (e.g., short-form video, social media) is associated with a reduced attention span and a diminished ability to engage in critical thinking. This “shallow learning” is characterized by the passive consumption of content rather than active interrogation.

Educational data indicates that while digital tools can enhance reaction times and cognitive flexibility, excessive use creates a “dualistic” impact: improvements in multitasking come at the cost of diminished capacity for focused, deep cognitive processing. This trade-off is particularly detrimental during early developmental stages, where foundational executive functions are being established.

Handwriting vs. Typing: The Motor-Cognitive Connection

The shift from handwritten to typed notes is another domain where technological efficiency undermines cognitive depth. A meta-analysis comparing these two modalities revealed that while typing allows students to record a greater volume of information (verbatim transcription), handwriting leads to significantly higher academic achievement and conceptual understanding.

The cognitive mechanism here is “generative processing.” Because handwriting is slower, the learner is forced to listen, digest, and summarize the information in real-time, translating it into their own words. This synthesis creates stronger memory traces. Typing, by contrast, can become a mindless transcription task that bypasses deep cognitive engagement.

Neuroscientific studies using EEG support this distinction, showing that handwriting activates distinct brain regions associated with motor control and sensorimotor integration that typing does not. This “motor memory” aids in letter perception and literacy acquisition in ways that the binary action of pressing a key cannot replicate.

| Feature | Handwritten Notes / Paper Reading | Typed Notes / Screen Reading | Cognitive Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | Slower; limits volume. | Faster; allows near-verbatim capture. | Handwriting forces synthesis; typing encourages transcription. |

| Comprehension | Higher scores on conceptual tests. | Lower scores; “screen inferiority effect.” | Paper supports spatial mapping; screens induce skimming. |

| Brain Activation | Activates motor cortex & sensorimotor areas. | Activates linguistic & visual processing only. | Handwriting creates richer haptic-kinesthetic memory traces. |

| Metacognition | Higher accuracy in judging own learning. | Tendency to overestimate comprehension. | Screens create an illusion of competence. |

4. The Architecture of Distraction: Seductive Details and the Addiction Economy

Educational technology does not exist in a vacuum; it competes for attention in an economy designed to fragment it. To compete with entertainment apps, educational developers often incorporate “gamified” elements that inadvertently sabotage learning.

4.1 The Seductive Details Effect

The “seductive details effect” refers to the phenomenon where interesting but irrelevant details (e.g., cartoons, background music, tangentially related trivia) impede the learning of structural content. While these details are added to increase emotional engagement, they function as cognitive distractors.

Research indicates that seductive details divert attention away from relevant schemas (diversion) and disrupt the coherence of the mental model being constructed (disruption). In a study of multimedia learning, students exposed to seductive details performed worse on recall and transfer tasks than those given a minimalist presentation. While some recent studies suggest that explicitly signaling the irrelevance of these details might mitigate the harm, the safest instructional design principle remains minimalism. The inclusion of “fun” elements often creates a “Las Vegas effect”—a flashy, over-stimulating environment that captures the eyes but scatters the mind.

4.2 Variable Rewards and the Dopamine Loop

Perhaps the most pernicious import from the gaming and social media industries is the use of Variable Ratio Reinforcement Schedules. In behavioral psychology, a fixed ratio schedule (e.g., a reward after every 5 correct answers) creates a predictable response pattern. A variable ratio schedule (e.g., a reward after an average of 5 answers, but unpredictably spaced) creates the highest and most persistent rate of responding. This is the psychological mechanism behind slot machines.

Educational apps utilizing variable rewards (randomized badges, sounds, or “loot box” mechanics) effectively hijack the brain’s dopamine system. The uncertainty of the reward keeps the student clicking, but this engagement is behavioral, not cognitive. The student becomes fixated on the anticipation of the reward rather than the content of the lesson. This can lead to “addiction-like” behaviors where the metric of success is the accumulation of digital tokens rather than the acquisition of knowledge.

4.3 Loot Boxes and Predatory Design

The ethical implications of these mechanics are severe. The integration of “loot boxes”—virtual items that can be earned or purchased to receive a random reward—into gamified learning environments has been linked to problematic gambling tendencies. Researchers argue that these “predatory monetization” schemes (or predatory engagement schemes in non-monetized contexts) exploit psychological vulnerabilities, particularly in children. When a learning platform uses the same psychological triggers as a casino, it raises fundamental questions about whether the goal is education or mere retention within the ecosystem.

5. Behavioral Analytics: Detecting the Early Signals of Failure

How can an educator or administrator know early if a specific technology is failing their students? Educational Data Mining (EDM) has identified specific behavioral “fingerprints” that signal cognitive disengagement long before a failing grade appears.

5.1 Gaming the System: Hint Abuse and Rapid Guessing

“Gaming the system” is defined as attempting to succeed in an educational environment by exploiting the properties of the software rather than by learning the material. This is a rational response to poorly designed incentive structures where completion is valued over mastery.

Two primary behaviors characterize gaming:

- Hint Abuse: The student rapidly clicks through a sequence of hints (e.g., < 2 seconds per hint) to reach the “bottom-out” hint, which usually contains the answer. The velocity of the clicks indicates that the student is not reading or processing the hints but merely searching for the solution.

- Rapid Guessing (Guess-and-Check): The student inputs answers at a speed that precludes actual cognitive processing (e.g., answering a complex physics problem in 3 seconds).

These behaviors are strongly correlated with poor learning outcomes and future academic failure. Advanced detection systems now use Response Time Effort (RTE) metrics to differentiate between “solution behavior” and “rapid-guessing behavior.” By establishing response time thresholds—often dynamically calculated using genetic algorithms based on item difficulty—systems can flag “non-effortful” attempts in real-time.

5.2 Wheel Spinning: The Tragedy of Unproductive Effort

While gaming implies a lack of effort, “Wheel Spinning” describes a student who is trying but failing to progress. It is defined as a state where a student fails to master a Knowledge Component (KC) despite significant practice.

Unlike productive struggle, which leads to learning, wheel spinning is characterized by a lack of convergence. The student may spend extensive time on a skill, but their probability of answering correctly does not improve over successive attempts. Detectors look for patterns of “decisiveness” in incorrect answers—students who keep trying (persistence) but lack the necessary scaffolding to succeed.

- Early Detection: Research suggests that wheel spinning can be predicted within the first 3 to 6 practice opportunities. If a student has not mastered a skill after this window, additional unguided practice is usually futile and leads to frustration and dropout.

5.3 Mindless Clicking and “Zombie” Behaviors

In game-based learning or simulations, disengagement can manifest as “mindless clicking” (sometimes called “chicken clicking”). This behavior involves repetitive, non-strategic interactions with the interface—clicking on every object in a room, or selecting random options without reading. It indicates a decoupling of action from cognition; the student is physically interacting but cognitively absent.

Similarly, “Zombie” behaviors have been observed in educational games, where students find a safe, repetitive loop (e.g., pausing the game repeatedly to avoid enemies) that allows them to bypass the educational challenge. These behaviors are often essentially “compliance” strategies—the student is doing something to appear busy or meet a time requirement, but no learning is occurring.

5.4 Stopout and Task Abandonment

In online environments like MOOCs or self-paced K-12 platforms, attrition follows a predictable decay curve. Stopout refers to a temporary cessation of activity, which may evolve into permanent dropout.

- Predictive Indicators: A sharp increase in the “time-to-first-correct” answer or a sudden drop in action logs (fewer clicks, longer pauses) often precedes abandonment.

- Thresholds: Task abandonment is often triggered when the “present bias” (the desire for immediate relief from the task) outweighs the perceived future value of completion. In students with learning disabilities, this threshold is often lower due to “learned helplessness,” leading to rapid task abandonment following a single failure.

| Behavioral Signal | Operational Definition | Metric for Detection | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaming the System | Exploiting software to avoid learning. | Hint Velocity: > 1 hint per 2 sec. Rapid Guessing: Answer time < 3 sec. | Student values completion over learning; intervention required to reset motivation. |

| Wheel Spinning | High effort without mastery progress. | Mastery Probability: No increase after 5-10 attempts. Time on Task: High duration with low success. | Student lacks prerequisite knowledge or scaffolding; immediate teacher intervention needed. |

| Mindless Clicking | Non-strategic, repetitive interaction. | Click Variance: Random distribution of clicks. Pattern Repetition: Repeating failed sequences. | Cognitive decoupling; student is “zombie” walking through the task. |

| Stopout | Cessation of activity with risk of dropout. | Action Decay: Sudden drop in interaction freq. Time Gaps: Extending intervals between logins. | Frustration threshold reached; “nudge” or support required to prevent dropout. |

6. Misconceptions, Simulations, and the Black Box Effect

A critical danger of sophisticated educational technology is its ability to mask a lack of understanding.

A student can learn to manipulate a simulation perfectly while harboring fundamental misconceptions about the physical reality it represents.

6.1 The Black Box Effect and AI Trust

As AI tools become more prevalent, the “Black Box” effect becomes a significant pedagogical risk. When a system automates intermediate steps (e.g., a math solver that gives the answer, or a simulation that simplifies friction), students may learn the “interface” rather than the “content.”

Furthermore, reliance on AI leads to “Techno-Over-Reliance” or blind trust. Students may accept AI-generated hallucinations or incorrect outputs because they view the computer as an infallible authority. This erodes critical thinking and the habit of verification, replacing it with a passive acceptance of algorithmic output.

6.2 Simulation Misconceptions

Simulations are powerful but perilous. If a simulation simplifies a concept—for example, a chemistry visualization that depicts atoms as solid spheres—students often internalize the model as literal reality. Research indicates that students can interact with a simulation for hours and yet retain deep misconceptions because they interpret the visual feedback through the lens of their existing (incorrect) beliefs. The “smoothness” of the simulation can reinforce these errors by preventing the cognitive conflict necessary for conceptual change.

6.3 Diagnostic Tool: Distractor Analysis and Concept Inventories

To detect these hidden failures, educators must employ Distractor Analysis. In rigorous assessments like Concept Inventories (e.g., the Force Concept Inventory in physics), the incorrect answers (distractors) are not random; they are carefully designed to correspond to specific, common misconceptions.

By analyzing which wrong answers a student selects, educators can diagnose the specific cognitive error. For example, if a student consistently selects distractors implying that “motion implies a force,” the system can flag a specific Newtonian misconception. Learning Management Systems (LMS) that aggregate this data can generate “misconception profiles,” allowing for targeted remediation that addresses the root cause of the error rather than just the symptom.

7. Instructional Design Solutions: Restoring Cognitive Integrity

The solution to these technological failures lies in rigorous instructional design that prioritizes cognitive architecture over user experience (UX) fluency.

7.1 Productive Failure: Designing for Struggle

To counteract shallow learning, systems should be designed for Productive Failure (PF). This instructional paradigm flips the traditional “teach-then-practice” model. In PF, students are presented with complex, ill-structured problems before they receive any instruction. They attempt to solve these problems, inevitably failing or generating suboptimal solutions.

This “failure” is productive because it activates prior knowledge, highlights knowledge gaps, and creates a “need to know.” When the canonical solution is finally introduced (consolidation phase), the student’s brain is primed to integrate the new information. Research shows that PF leads to significantly deeper conceptual understanding and transfer compared to Direct Instruction, even though students often feel more frustrated during the process.

- Implementation: Edtech should not always guide students to the correct answer immediately. It should provide “scaffolding for struggle”—prompts that encourage reflection on why a solution failed, rather than merely correcting it.

7.2 The Cognitive Load Audit Framework

Before adopting any new technology, educational institutions should conduct a Cognitive Load Audit based on the principles of Mayer and Sweller.

The Audit Checklist:

- Redundancy Check: Is there verbatim on-screen text and narration? If yes, mute one.

- Split-Attention Check: Are diagrams and their explanations spatially integrated? If not, the tool imposes unnecessary load.

- Seductive Details Check: Are there animations, sounds, or games that do not directly support the learning objective? These should be removed or made optional.

- Pacing Control: Does the learner have control over the speed of information presentation? Auto-playing videos without pause/segmentation violate the limited capacity assumption of working memory.

7.3 Scaffolding and the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

Effective technology must adapt to the learner’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)—the space between what a learner can do alone and what they can do with guidance.

- Dynamic Scaffolding: Systems should provide heavy support (worked examples, hints) for novices to reduce frustration (wheel spinning), and gradually fade this support as expertise increases (fading).

- Expertise Reversal Effect: Crucially, support that helps a novice can actually hinder an expert (extraneous load). Adaptive systems must detect mastery and remove scaffolding to prevent this “expertise reversal”.

8. Conclusion: From Engagement to Cognition

The evidence presented in this report suggests that the relationship between technology and learning is not linear; it is a precarious balance between access and overload. Technology makes learning worse when it violates the fundamental limits of human cognitive architecture—when it buries the learner in redundant information, fragments their attention with seductive details, or encourages shallow behavioral loops like gaming and mindless clicking.

To “know early” if technology is failing, educators must move beyond the vanity metrics of “engagement” and “completion.” They must adopt a forensic approach to behavioral analytics, looking for the tell-tale signs of cognitive dropout: the rapid guess, the abused hint, the repetitive click, and the persistent misconception.

Ultimately, the goal of educational technology should not be to make learning “easy” or “fun” in the superficial sense of a game. True learning is often difficult, slow, and filled with friction. The role of technology is to ensure that this friction is productive—directed at the complexity of the content itself—rather than unproductive friction generated by poor design. By auditing our tools for cognitive load and designing for productive struggle, we can reclaim the digital classroom as a space for deep, sustained, and meaningful human thought.