Classroom Tech Ethics: Active Learning for Digital Citizens

Introduction: The Imperative for Active Ethical Engagement

The integration of digital technology into the fabric of modern education has fundamentally altered the landscape of teaching and learning. However, alongside the tangible benefits of connectivity and information access, a complex web of ethical dilemmas has emerged. Issues surrounding data privacy, algorithmic bias, artificial intelligence (AI), and digital consent are no longer peripheral concerns but central challenges to the development of responsible citizenship. Historically, digital citizenship education has relied heavily on a compliance-based model—a “lecture” approach focused on prohibitions: do not share passwords, do not cyberbully, do not plagiarize. While these rules remain relevant, this defensive posture fails to equip students with the critical thinking skills necessary to navigate a digital ecosystem characterized by surveillance capitalism, generative AI, and shifting social norms.

A growing body of research suggests that to truly prepare students for the complexities of the digital age, educators must pivot from passive instruction to active, inquiry-based learning. The modern student does not merely need to be told that privacy is important; they need to experience the mechanisms of data collection to understand the economy of attention that governs their lives. They do not need a lecture on the definition of bias; they need to interrogate the outputs of machine learning models to identify the prejudices encoded within them. This report outlines an exhaustive pedagogical framework for teaching ethical technology use through the lens of student agency. It explores strategies that transform the classroom into a laboratory for ethical reasoning, utilizing methodologies such as Project-Based Learning (PBL), Structured Academic Controversies (SAC), and Thinking Routines developed by Harvard’s Project Zero.

The urgency of this shift is underscored by the rapid evolution of technology itself. The static rules of the past are insufficient for the dynamic challenges of the present, such as the rise of invasive proctoring software during remote learning or the ethical ambiguities of AI-generated content. By engaging students in “low-stakes practice” with digital tools and fostering environments where “talking and listening” are foundational, educators can help students internalize ethical concepts rather than simply memorizing them. This report details the theoretical underpinnings and practical applications of these active learning strategies, offering a roadmap for educators to foster a generation of digital citizens who are not just compliant users, but critical, conscientious participants in the digital world.

Theoretical Foundations of Active Digital Ethics

To effectively teach digital ethics without resorting to lectures requires a robust understanding of the pedagogical theories that support active learning. The shift is from a behaviorist model—where the goal is to modify student behavior through rewards and punishments—to a constructivist model, where students build their own understanding of ethical principles through experience and reflection.

The Role of Constructivism and Inquiry-Based Learning

Constructivism posits that learners construct knowledge rather than passively taking in information. In the context of digital ethics, this means that students must actively grapple with dilemmas to form their own ethical frameworks. Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL) serves as a primary vehicle for this. Instead of delivering answers, the educator poses open-ended, driving questions that require investigation and synthesis. For example, rather than explaining the concept of “Digital Citizenship,” a teacher might ask, “How does our online behavior impact our offline communities?” or “Who owns our data?”

The application of IBL in social studies and technology curricula allows for a seamless integration of digital ethics into broader discussions of rights, governance, and justice. Research indicates that inquiry-based social studies can foster curiosity and ownership of learning. This approach involves four major steps:

- Question Development: Students formulate questions that cannot be answered with a simple search, requiring them to “pitch” ideas and construct responses.

- Research: Students investigate artifacts, policies, or datasets—such as analyzing the “terms of service” of a favorite app or researching the history of surveillance.

- Presentation: Findings are shared with an authentic audience, moving beyond the teacher-student loop to engage peers or community members.

- Reflection: Students consider how their understanding has evolved, a critical step for solidifying ethical reasoning.

This methodology transforms the classroom dynamic. The teacher becomes a facilitator of “talking and listening,” which are critical components of active learning. By articulating their thoughts and hearing diverse perspectives, students clarify their own understanding and develop the cognitive flexibility required to navigate complex ethical landscapes.

Project-Based Learning (PBL) and Authentic Contexts

Project-Based Learning (PBL) extends the principles of inquiry by organizing learning around the creation of a tangible product that addresses a real-world problem. In digital ethics, PBL is particularly effective because it grounds abstract concepts in concrete reality. When students are tasked with creating a “product”—whether it be a policy recommendation, a public service announcement, or a technical tool—they must engage deeply with the subject matter.

A compelling example of this is the use of “escape rooms” to teach digital literacy. In one case study, a sixth-grade teacher had students design their own escape room activities, developing narratives, puzzles, and clues using digital tools like QR codes. This project required students to not only use the technology but to understand its mechanisms and potential pitfalls. The “creator” mindset fosters a sense of agency that is often lacking in traditional instruction.

Furthermore, PBL allows for “authentic audiences.” Research suggests that when students create work for an audience beyond the teacher—such as parents, other students, or school administrators—engagement and quality increase. For instance, students might conduct a “Digital Citizenship Audit” of their school and present their findings to the principal, or create a guide on “AI Safety” for younger students. This approach aligns with the ISTE Standards for Students, particularly the “Digital Citizen” strand, which emphasizes using technology to engage in positive, safe, and legal behavior.

The “Slow Complexity” of Thinking Routines

In a digital world characterized by speed and instant gratification, teaching ethics requires slowing down the thinking process. “Thinking Routines,” developed by researchers at Harvard’s Project Zero (PZ), provide simple, repeated structures that scaffold thinking and make it visible. These routines are designed to help students bypass their initial, reactive judgments and engage in “slow complexity capture”.

Research by Carrie James and Emily Weinstein at Project Zero highlights that young people constantly navigate “digital dilemmas” that lack clear right or wrong answers. The use of Thinking Routines helps students develop “dispositions” for thoughtful engagement—habits of mind that persist outside the classroom.

Table 1: Key Thinking Routines for Digital Ethics Inquiry

| Routine | Cognitive Purpose | Application in Digital Ethics |

|---|---|---|

| See, Think, Wonder | Encourages careful observation and interpretation. | Analyzing a complex image of a data center, a visualization of a social network, or a screenshot of a “dark pattern” in UI design. |

| Feelings and Options | Scaffolds perspective-taking and empathetic problem-solving. | Exploring a scenario where a student is pressured to share a password or an embarrassing photo. Students identify feelings of all parties and brainstorm options. |

| Tug of War | Explores the complexity of fairness dilemmas and opposing forces. | Debating the use of facial recognition in schools or the banning of smartphones. Students identify “tugs” regarding security vs. privacy. |

| Unveiling Stories | Reveals multiple layers of meaning and missing narratives. | Analyzing news reports on AI bias to determine whose stories are told (“The Human Story”) and whose are omitted (“The Untold Story”). |

| Compass Points | Helps evaluate a new idea or proposition from multiple angles. | Assessing a school’s new “Responsible Use Policy.” (Excited, Worrisome, Need to Know, Stance). |

| 3-2-1 Bridge | Tracks the evolution of thought over time. | Students record 3 thoughts, 2 questions, and 1 analogy about “Privacy” before and after a unit to see how their thinking has shifted. |

These routines are not merely activities but “patterns of behavior” that, when used repeatedly, shape how students approach all digital interactions. They provide a language for discussing ethics that is structured yet flexible, allowing for the exploration of “gray areas” that lectures often gloss over.

The Architecture of Surveillance: Teaching Data Privacy

Data privacy is often the most abstract concept for students to grasp. In an era of “free” apps and seamless connectivity, the transaction of data for services is invisible. To teach this without lecturing requires making the invisible visible through simulation, analysis, and analogical reasoning.

Unplugged Simulations: The Tangibility of Data

“Unplugged” activities—teaching computer science concepts without the use of computers—are highly effective for isolating ethical principles from the distractions of the device.

By removing the screen, educators can focus on the mechanisms of data collection.

The Cookie Jar Simulation

- The Setup: As students enter the classroom, they are given a physical token (a “cookie”).

- The Activity: Stations around the room represent different websites. As students visit these stations to complete small tasks, they must show their cookie to the “site owner” (a peer or teacher), who records their ID number on a public ledger.

- The Reveal: At the end of the activity, the instructor reads back the “browse history” of specific students, demonstrating how isolated data points—visiting a sports site, then a medical site, then a shopping site—can be aggregated to build a detailed profile.

- The Debrief: Students engage in a “Pros/Cons” discussion. They debate the trade-off between convenience (not logging in repeatedly) and privacy (being tracked). This visceral demonstration makes the abstract concept of HTTP cookies concrete and personal.

The “Value of Privacy” Market

Another powerful unplugged activity involves a “Data Market” game. Students are given a set of “privacy assets” (e.g., their location, their friends list, their private messages). They are then offered “free” services (e.g., a game, a social network) that require payment in these assets. As the game progresses, the cost of services increases—demanding more invasive data. This simulation models the Terms of Service economy, forcing students to make value judgments about what their privacy is worth. It directly addresses the curriculum goal of understanding how systems market products through personalized user profiles.

3.2 Analyzing the “Fine Print”: Terms of Service as Literature

Terms of Service (TOS) agreements are the legal bedrock of the digital world, yet they are notoriously unread. An active learning strategy involves treating these documents as primary source texts for analysis, much like a historical treaty or a piece of literature.

The “Bogus Contract” Provocation

To immediately engage students in the importance of reading contracts, an educator can utilize a “bogus contract” at the start of a unit. In one case study, an instructor included absurd clauses in a class agreement—such as requiring students to bring donuts on Fridays or essentially signing away their rights—which students blindly signed. The reveal of these clauses serves as a powerful “gotcha” moment that highlights the dangers of passive consent. This experiential learning is far more impactful than a warning to “always read the fine print.”

TOS Forensics

Following the provocation, students can engage in a “TOS Detective” activity. Working in small groups, they analyze the Terms of Service of popular applications (e.g., TikTok, Instagram, or educational tools used by the school). They are guided to look for specific “red flags” and categories:

- Data Collection: What specific data is collected? Does it include metadata, location, or biometric data?

- Third-Party Sharing: Who is the data shared with? Does the company sell data to advertisers?

- Rights to Content: Does the user retain ownership of the photos and videos they upload?

- Modification Clauses: Can the company change the terms without notifying the user?

Students can use a “checklist” framework provided by privacy organizations to evaluate whether an app is safe or “risky”. This transforms the dense legalese into a scavenger hunt for ethical violations. The discussion then moves to consumer rights and corporate ethics, asking whether it is ethical for companies to hide invasive practices in complex legal language.

3.3 Case Study: The Ethics of Proctoring Software

The rapid adoption of remote proctoring software (e.g., Proctorio, Honorlock) during the COVID-19 pandemic provides a rich, contemporary case study for privacy ethics. These tools often employ invasive monitoring techniques, such as eye-tracking, room scans, and AI-driven behavior analysis.

The Controversy:

Proctoring software is justified by institutions as a necessary tool to maintain academic integrity and the value of degrees. However, students and privacy advocates argue that it constitutes “legitimized spyware” and a violation of the Fourth Amendment (protection against unreasonable searches) when it scans a private bedroom. Furthermore, there are significant concerns about bias, as the software may flag neurodivergent students (who may look away from the screen frequently) or students with darker skin tones (whom the facial detection software may fail to recognize) as “suspicious”.

Active Learning Activity: Tug of War

This scenario is ideal for the Tug of War thinking routine.

- The Rope: A physical or digital line is drawn, with one end representing “Academic Integrity/Security” and the other “Student Privacy/Equity.”

- The Tugs: Students write arguments on sticky notes that “tug” the issue toward one side.

- Integrity Tug: “Degrees lose value if everyone cheats.” “It’s unfair to honest students if others cheat.”

- Privacy Tug: “Room scans invade the privacy of family members.” “The software is biased against certain bodies.” “It causes undue anxiety.”

- The Dialogue: Students place their notes on the line and discuss the “knots”—areas where valid competing values clash. The goal is not to declare a winner but to understand the complexity. Is there a way to ensure integrity without invasion? (e.g., open-book exams, project-based assessments).

This activity moves the discussion from a binary “good vs. bad” debate to a nuanced exploration of proportionality and necessity in surveillance.

4. The Black Box: Teaching AI Bias and Ethics

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is often perceived by students as a neutral, objective calculator. “The computer said so” carries a weight of authority. A critical component of active digital ethics is dispelling this myth and revealing the human decisions—and human biases—embedded in algorithms.

4.1 Deconstructing Generative AI

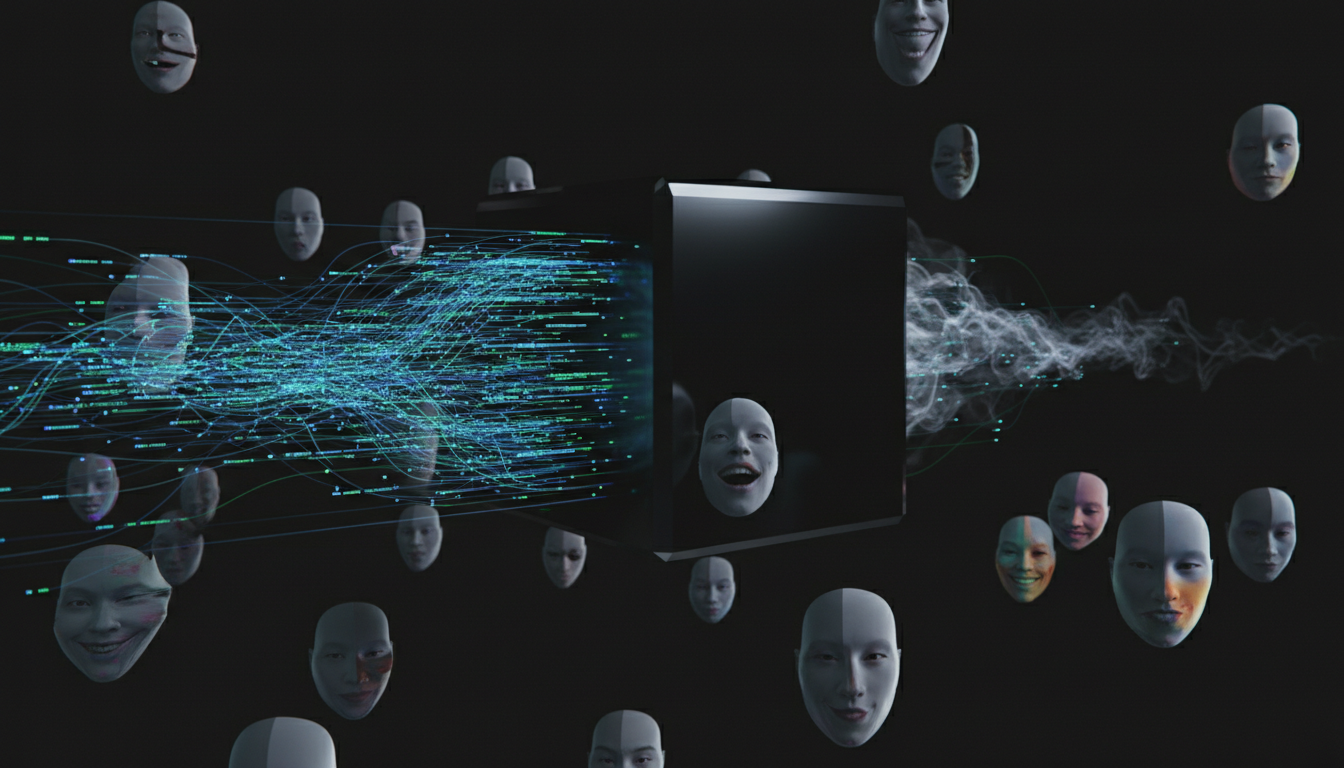

Generative AI models (like ChatGPT and Midjourney) are trained on vast datasets scraped from the internet. Because the internet contains human prejudices, these models inevitably reproduce them. Teaching this requires students to “audit” the AI.

The Bias Audit Activity

An experiential approach involves students acting as researchers to uncover bias in generative tools.

- Concept Introduction: The instructor briefly introduces the concepts of “Linguistic Bias” (predominance of English/Western perspectives) and “Statistical Bias” (how data selection affects output).

- The Experiment: Students work in teams to prompt an AI image generator or text generator with open-ended requests.

- Prompts: “Generate an image of a CEO,” “a doctor,” “a nurse,” “a criminal,” or “a person cleaning a house.”

- Data Collection: Students analyze the results. Are the CEOs predominantly white men? Are the nurses predominantly women? Are the “criminals” disproportionately people of color?

- Reflective Inquiry: Students then engage the AI in a meta-discussion, asking it: “What kinds of bias might appear in your output?” and “Why might your output include gender bias?” This forces the student to critique the tool using the tool itself.

- Discussion: The class synthesizes their findings. They discuss the implications of “Individualism vs. Collectivism” in AI training data—how Western values of individualism may dominate the “personality” of the AI, marginalizing other cultural worldviews.

Equity and Access

Beyond bias, students must consider the “digital divide.” Who has access to these premium AI tools? Discussion points include the disparity between students who can afford $20/month for advanced AI tutors and those who cannot, potentially widening the achievement gap.

4.2 Facial Recognition and the School Environment

Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) is increasingly being marketed to schools for security (e.g., identifying threats) and efficiency (e.g., taking attendance). This creates a high-stakes ethical environment suitable for deep inquiry.

The Evidence Landscape

- Proponents argue that FRT can “harden” schools against violence and streamline administrative tasks.

- Critics point to the “institutionalization of inaccuracy.” Studies show FRT is significantly less accurate for women and people of color, leading to false identifications. Furthermore, it normalizes a culture of surveillance, potentially eroding the trust essential for a learning environment.

Activity: The School Board Simulation

Students can take on the role of a School Board deciding whether to purchase an FRT system.

- Roles: Students are assigned perspectives: The Tech Vendor (focused on safety/sales), The Concerned Parent (privacy), The Student Advocate (civil rights), and The School Administrator (efficiency).

- The Task: They must review “bids” and “impact assessments.” They use the Compass Points routine to evaluate the proposal:

- North (Need to Know): What is the error rate? Who owns the data?

- East (Excited): Faster lines at the cafeteria? Safer campus?

- West (Worrisome): False arrests? Biased policing?

- South (Stance): Vote on the implementation.

This simulation forces students to weigh safety against liberty, a classic civic dilemma recontextualized for the digital age.

4.3 Algorithmic Grading: The Case of the “Mutant Algorithm”

The use of algorithms to grade student work or predict exam results provides a tangible example of how “math” can create injustice.

Case Study: The UK A-Levels Fiasco

During the pandemic, the UK government used an algorithm to assign A-Level grades since exams were canceled.

The algorithm used historical school performance data to adjust grades.

The result was that high-achieving students in historically lower-performing schools (often in lower-income areas) were downgraded, while students in private schools saw grade inflation.

- Analysis: Students examine the “inputs” of the algorithm. They discover that the system valued statistical patterns over individual merit.

- Thinking Routine: Unveiling Stories.

- The Story: A computer graded tests to save time.

- The Human Story: Students lost scholarships and university placements; mental health crises ensued.

- The Untold Story: The decision by policymakers to prioritize “grade distribution stability” over individual fairness.

- The New Story: The protest chant “Fk the algorithm” represented a new form of civic engagement—algorithmic resistance.

This case study demonstrates that algorithms are not “black boxes” of magic but “opinions embedded in code”.

5. Digital Intimacy: Consent, Boundaries, and Relationships

Teaching consent in the digital age requires moving beyond legal definitions to the social and emotional nuances of interpersonal relationships. Issues like sexting, photo sharing, and “digital drama” are often governed by unspoken social codes that students must learn to navigate explicitly.

5.1 The Psychology of Digital Consent

Consent education often fails because it focuses on strangers. However, most digital violations occur between friends or partners. “Consent” in a digital context is about boundaries, permission, and respect.

The “Feelings and Options” Routine

This routine is specifically designed to handle the emotional weight of social dilemmas.

- Scenario: A student, Alex, takes a funny but unflattering picture of a friend, Sam, at a sleepover. Alex wants to post it to a “Finsta” (fake/private Instagram) because it will get laughs. Sam typically laughs at himself, but tonight he seems quiet.

- Step 1: Identify: Who is involved? (Alex, Sam, the other friends at the sleepover, the online audience).

- Step 2: Feel: What is Alex feeling? (Desire for social validation, fun). What is Sam feeling? (Insecurity, perhaps pressure to be a “good sport”).

- Step 3: Imagine Options: Brainstorm actions without judgment.

- Post it.

- Ask Sam first.

- Don’t post it.

- Send it to Sam privately.

- Step 4: Decide: Choose the option where the most people feel respected and “taken care of.”

This routine builds “empathic problem-solving” skills. It helps students recognize that just because they can post something doesn’t mean they should.

5.2 The “Digital Permission Slip”

To make the abstract act of “asking for consent” concrete, educators can use a role-playing activity centered on “permission slips”.

- Activity: Students are tasked with “curating” a class photo album. Before they can “upload” (stick a photo on the board), they must obtain a “Digital Permission Slip” from the subject.

- The Nuance: The permission slip isn’t just a signature. It includes questions: “Can I tag you?” “Can I share this with parents?” “Can I use this for a meme?”

- Discussion: This highlights that consent is specific and revocable. A student might consent to a photo being shared with the class but not on a public website. This mirrors the “granular consent” options found in privacy settings, reinforcing the link between social ethics and technical configuration.

5.3 De-escalating Digital Drama

Conflict is inevitable. The “Digital Drama Unplugged” activity provides a framework for conflict resolution.

- The Simulation: Students are given a script of a group chat that is spiraling into conflict (exclusion, rumors, or misinterpretation of tone).

- The Freeze: At a critical moment, the teacher freezes the action.

- The Intervention: Students must propose a “de-escalation move.”

- Move 1: “Take it offline.” (Stop texting, start talking).

- Move 2: “Assume positive intent.” (Did they mean to be rude, or was it a typo?).

- Move 3: “Use an ‘I’ statement.” (“I feel hurt when…” instead of “You are being…”).

- The Insight: Students learn that the medium of text often strips away empathy-inducing cues (tone of voice, facial expression), making conflict more likely. The active rehearsal of these moves builds “muscle memory” for when real drama occurs.

6. The Classroom as Forum: Managing Controversy

When digital ethics topics touch on political or identity-based issues (e.g., hate speech regulation, net neutrality), the classroom can become polarized. Lecturing on “civility” is rarely effective. Instead, educators need structured discussion formats that force students to listen.

6.1 Structured Academic Controversy (SAC)

The Structured Academic Controversy (SAC) is a cooperative learning strategy designed to move students from “debate” (where the goal is to win) to “deliberation” (where the goal is to understand). It is particularly effective for high-stakes digital topics.

The Protocol Step-by-Step:

- Topic Selection: Choose a binary controversy, e.g., “Should social media companies be held liable for content posted by users?” (Section 230 debate).

- Grouping: Form groups of four, divided into two pairs (Pair A and Pair B).

- Position Assignment: Pair A is assigned “Pro-Liability”; Pair B is assigned “Anti-Liability.”

- Preparation: Pairs research their assigned position using provided text sets (legal briefs, op-eds). They must build the strongest possible case for their side regardless of their personal opinion.

- Presentation (The Critical Step): Pair A presents their case. Pair B listens and takes notes. Pair B cannot interrupt or argue.

- Restatement: Pair B must repeat Pair A’s arguments back to them. Pair A must confirm: “Yes, that is what we said.” If not, Pair B must try again. This forces “active listening”.

- Reversal: The process repeats with Pair B presenting and Pair A listening/restating.

- Consensus: The pairs drop their roles. The group of four discusses the issue as themselves. They attempt to reach a consensus or, more likely, draft a “joint statement” that acknowledges the complexity and valid points on both sides.

Why SAC Works: By forcing students to articulate the opposing view to the satisfaction of their opponents, SAC breaks down the “straw man” fallacy. It builds intellectual humility and demonstrates that complex digital issues rarely have simple solutions.

6.2 Teacher Neutrality vs. Committed Impartiality

A common challenge in active ethics education is the role of the teacher. Should the teacher be neutral?

- The Neutrality Trap: Absolute neutrality can be problematic if it suggests that all viewpoints are ethically equal (e.g., “Is cyberbullying acceptable?”). Research suggests that “neutrality” in the face of dehumanization is an ethical stance in itself.

- Committed Impartiality: A more robust approach is “committed impartiality” or “balanced analysis.” The teacher ensures that all empirical and reasoned perspectives are heard but does not validate factually incorrect or harmful rhetoric (e.g., hate speech).

- Facilitation Techniques: When a discussion heats up, the teacher can use “The Round” (everyone speaks once before anyone speaks twice) or “Think-Pair-Share” (writing before speaking) to lower the temperature and allow for processing time.

7. Assessment and Curriculum Integration

In an active learning framework, assessment cannot be a simple multiple-choice quiz. If the goal is ethical reasoning, the assessment must measure the quality of thought, not just the recall of facts.

7.1 Rubrics for Ethical Reasoning

Assessment rubrics should focus on the dimensions of digital citizenship: critical thinking, empathy, and responsibility.

Table 2: Sample Dimensions for a Digital Ethics Rubric

| Dimension | Emerging | Developing | Proficient | Exemplary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilemma Recognition | Unable to identify the ethical conflict. Sees issue as black/white. | Identifies the conflict but struggles to articulate the tension. | Clearly articulates the ethical dilemma and the competing values (e.g., privacy vs. safety). | nuanced articulation of the dilemma, including secondary impacts and unintended consequences. |

| Perspective Taking | Considers only one perspective (usually their own). | Acknowledges other perspectives but dismisses them without analysis. | Accurately represents opposing viewpoints with fairness. | empathetic engagement with multiple stakeholders; identifies valid needs on all sides. |

| Evidence-Based Reasoning | Relies on opinion or anecdote only. | Uses some evidence but relies heavily on unsupported claims. | Supports arguments with relevant facts, data, or text evidence (e.g., TOS clauses, case studies). | Synthesizes multiple sources of evidence to build a sophisticated, well-supported argument. |

| Solution Design | Proposes simplistic solutions that ignore trade-offs. | Proposes solutions that address the immediate problem but miss broader implications. | Proposes viable solutions that balance competing needs. | creative, systemic solutions that address root causes and mitigate harm for vulnerable groups. |

7.2 Scope and Sequence: Building a Spiral Curriculum

Ethical education must be longitudinal. A “one-off” assembly is insufficient. A spiral curriculum introduces concepts at age-appropriate levels and deepens them over time.

- Elementary (K-5): Focus on “Safety and Security” and “Digital Footprint.” Unplugged activities like “The Internet Traffic Light” (Stop/Think/Go) are appropriate here.

The concept of “asking permission” is introduced through physical interactions.

- Middle School : Focus on “Social Media dynamics,” “Cyberbullying,” and “Identity.” This is the prime age for “Digital Drama” simulations and “Feelings and Options” routines, as peer relationships are paramount.

- High School : Focus on “Civic Engagement,” “AI Ethics,” and “Legal Rights.” High schoolers should engage in SACs regarding facial recognition, algorithmic bias, and privacy laws. They should be “auditing” the tools they use.

Aligning with Standards

This active framework aligns directly with the ISTE Standards for Students:

- 1.2 Digital Citizen: Students recognize the rights, responsibilities, and opportunities of living in an interconnected digital world.

- 1.3 Knowledge Constructor: Students critically curate information (evaluating AI bias and “fake news”).

- 1.7 Global Collaborator: Students use digital tools to broaden their perspectives and understand the “Global Story.”

Conclusion: From Compliance to Agency

The transition from a lecture-based model of digital citizenship to an active, inquiry-based framework is not merely a pedagogical preference; it is a necessity for the health of our digital society. By treating students as active agents—capable of deconstructing algorithms, negotiating consent, and debating policy—educators empower them to shape the future of technology rather than merely enduring it.

The strategies outlined in this report—from the “slow thinking” of Project Zero routines to the “unplugged” simulations of data tracking—share a common goal: to make the invisible visible. When students can see the bias in an image generator, feel the tension of a privacy dilemma, and hear the opposing view in a structured controversy, they develop a depth of understanding that no slide deck can provide.

As schools implement these strategies, they move beyond the goal of “keeping kids safe” to the broader, more ambitious goal of “cultivating digital wisdom.” This wisdom is the foundation of a democratic society in the 21st century—a society where technology serves human dignity, and where every user is also a citizen.

Key Recommendations for Implementation

- 1. Start Small: Introduce one Thinking Routine (e.g., See, Think, Wonder) and use it consistently across different topics to build student familiarity.

- 2. Use the Analog: Whenever possible, teach the concept without the device first (e.g., the Cookie Jar) to isolate the ethical principle.

- 3. Center Student Voice: Involve students in the creation of Responsible Use Policies. When they help write the rules, they are more invested in the ethics behind them.

- 4. Embrace the Gray: Resist the urge to provide “the answer.” The most valuable learning happens in the struggle to reconcile competing values.

By embracing these pedagogies of agency, educators can transform the challenge of digital ethics into an opportunity for profound intellectual and moral growth.