Campaign Data: Impact Metrics for Electoral Victory

Chapter 1: The Epistemology of Campaign Measurement

1.1 The Moneyball Era and Its Discontents

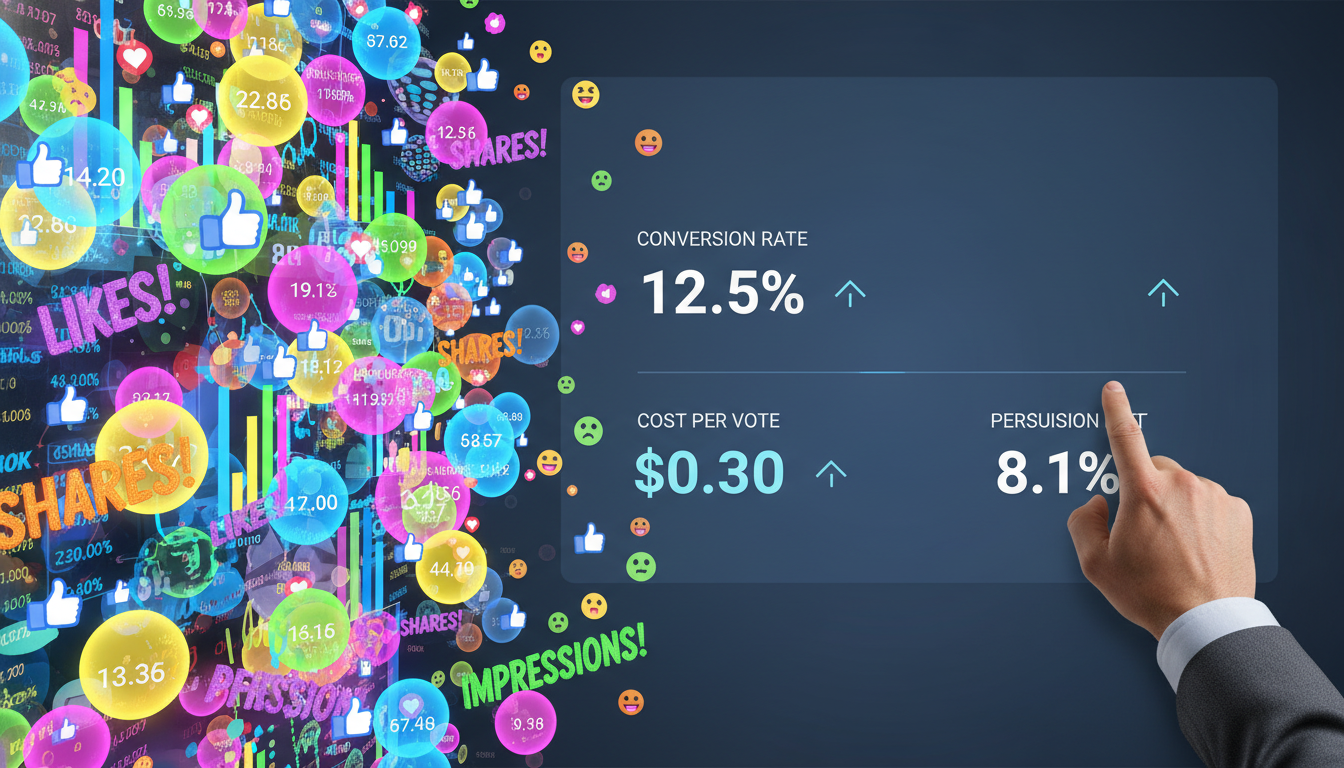

The modern political campaign is an enterprise drowning in data yet frequently starving for wisdom. We have transitioned from the era of the “smoke-filled room,” where decisions were driven by intuition and patronage, to the era of “Moneyball politics,” where every interaction is quantified, tracked, and modeled. The promise of this data revolution was a new age of efficiency, where resources would be allocated with surgical precision to the voters who mattered most. Yet, a paradox has emerged: as the volume of data has increased exponentially, the clarity of strategic insight has often diminished. Campaign leaders, overwhelmed by spreadsheets and real-time dashboards, often find themselves optimizing for the wrong variables. They chase “vanity metrics”—numbers that look impressive on a slide deck but have zero correlation with the only metric that ultimately matters: the 50% + 1 vote threshold required for victory.

This report serves as a comprehensive corrective to the prevailing pathology of modern campaign analytics. It argues that the reliance on surface-level indicators—”likes,” “door knocks,” “impressions”—is not merely an administrative oversight but a strategic fatal flaw that has doomed well-funded presidential bids and local races alike. By distinguishing between “output” (what the campaign does) and “outcome” (how the electorate changes), we establish a framework for Impact Metrics. These metrics, derived from rigorous methodologies like Randomized Control Trials (RCTs) and Uplift Modeling, allow campaigns to measure the intangible: persuasion.

The shift from vanity to impact is not just a technical upgrade; it is a cultural transformation. It requires campaign managers to abandon the comfort of “up and to the right” cumulative charts in favor of the harsh reality of conversion rates and efficiency scores. It demands that Field Directors stop celebrating the exhaustion of their volunteers and start measuring the quality of their conversations. It compels Digital Directors to look beyond the dopamine hit of a viral tweet to the sober math of Cost Per Persuadable Voter (CPP). This document outlines the theoretical underpinnings, practical applications, and technological infrastructure necessary to make that shift.

1.2 Defining the Core Conflict: Vanity vs. Impact

To navigate the data landscape, one must first understand the fundamental dichotomy between vanity and impact. Vanity metrics are defined by their superficiality and their disconnect from the campaign’s bottom line. They are “feel-good” numbers. In the corporate world, a vanity metric might be “registered users” for a platform that has no revenue; in politics, it is “total volunteers recruited” for a campaign that has no retention strategy. These metrics are dangerous because they are often cumulative; they always go up, creating an illusion of progress even as the campaign hurtles toward defeat.

Impact metrics, conversely, are actionable. They function as Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that inform decision-making. If a metric does not change how you behave—if it does not prompt you to fire a consultant, move resources to a different district, or change a creative asset—it is a vanity metric. Impact metrics are often ratios or rates (e.g., conversion rate, retention rate, cost per vote) rather than raw totals, providing a clearer picture of efficiency and effectiveness.

Table 1.1: The Taxonomy of Campaign Metrics

| Operational Domain | Vanity Metric (The Illusion of Success) | Impact Metric (The Reality of Victory) | Strategic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Operations | Doors Knocked: Measures physical exertion. A volunteer can knock on 100 doors in an empty neighborhood. | Contact Rate: (Conversations / Knocks). Measures the quality of the list and timing. Conversion Rate: (Pledges / Conversations). Measures the persuasiveness of the script. | High knocks with low contacts is a waste of human capital. Optimizing for contacts ensures the message is actually delivered. |

| Digital Media | Impressions/Views: Measures potential reach. Includes bots, passive scrolling, and non-voters. | Video Completion Rate (VCR): Measures attention. Cost Per Acquisition (CPA): Measures the efficiency of list building. | Paying for impressions that don’t convert to attention or action is burning cash. CPA aligns spend with list growth. |

| Social Media | Followers/Likes: Measures audience size, often global rather than local. | Engagement Rate: Measures the depth of interaction. Share of Voice (PSOV): Measures dominance in the conversation relative to opponents. | High followers means nothing if they are in California and you are running in Ohio. Engagement indicates enthusiasm that leads to volunteering. |

| Fundraising | Total Raised: Measures gross revenue. Ignores the cost of raising that money. | Cost to Raise a Dollar: Measures fundraising efficiency. Cash on Hand (COH): Measures solvency and “runway.” | A campaign that raises $1M but spends $900k to get it is functionally broke. COH dictates operational capacity. |

| Voter Sentiment | Rally Crowd Size: Measures the enthusiasm of the “already convinced.” | Net Sentiment Score: Measures the broader public mood via social listening. Persuasion Lift: Measures the shift in support among undecideds. | Crowds are self-selecting echo chambers. Sentiment analysis captures the silent majority’s drift. |

The persistence of vanity metrics is rooted in organizational psychology. Campaign staff are under immense pressure to validate their existence. A Field Director reporting “We knocked 50,000 doors this week!” receives applause. One reporting “We had a 2% contact rate, meaning we wasted 98% of our volunteer hours,” risks termination. Thus, the incentive structure of political campaigns often perverse aligns with the production of vanity data, shielding leadership from the “Ground Truth” until it is too late.

1.3 The “Lean Startup” Approach to Political Data

The principles of the Lean Startup methodology—specifically the “Build-Measure-Learn” feedback loop—are highly applicable to political campaigns.

- Hypothesis: “Voters in the suburbs are concerned about education.”

- Build: Create a digital ad and a canvass script focused on education.

- Measure: Track the engagement rate on the ad and the conversion rate at the door (Impact Metrics), not just the number of ads shown (Vanity Metric).

- Learn: If the engagement is low, the hypothesis is wrong. Pivot immediately.

Vanity metrics short-circuit this loop. If the campaign only measures “Impressions,” they may conclude the education message is working simply because 100,000 people saw it, failing to realize that 99% of them scrolled past it or reacted negatively. This failure to pivot is often what separates winning campaigns from losing ones.

Chapter 2: Case Studies in Metric Failure

To understand the stakes of data mismanagement, we must examine the graveyards of campaigns that mistook noise for signal. The history of modern campaigning is littered with operations that boasted impressive vanity metrics right up until their concession speeches.

2.1 The Beto O’Rourke Phenomenon : The Nationalization Distortion

- The Vanity Surge: O’Rourke’s livestreamed town halls, skateboarding videos, and impassioned speeches generated millions of views and likes. His fundraising shattered records, pulling in over $80 million, largely from small-dollar donors across the United States.

- The Metric Trap: The campaign’s dashboard likely showed “Green” across the board: record money, record views, record volunteer signups. These metrics suggested a wave election.

- The Impact Reality: The “likes” were largely coming from non-Texans. The fundraising, while helpful, created a “nationalization” of the race that motivated the Republican base as much as the Democratic one. The campaign’s internal metrics on youth turnout showed a massive surge (up 500% in early voting), which led to a belief that the electorate composition had fundamentally changed.

- The Outcome: O’Rourke lost. While he performed historically well for a Democrat in Texas, the vanity metrics masked the structural partisan lean of the state. The “viral” nature of the campaign created an echo chamber where online enthusiasm was mistaken for a decisive shift in the median voter’s preference. The lesson: Global engagement does not equal local votes. A dashboard that does not geo-fence its social metrics is a liability.

2.2 DeSantis 2024: The Echo Chamber of the “Very Online”

- The Twitter Launch: DeSantis chose to launch his campaign on Twitter Spaces with Elon Musk. This decision was driven by vanity metrics: the desire to generate “buzz,” “break the internet,” and appeal to high-engagement conservative influencers on the platform.

- The Metric Failure: The launch was plagued by technical failures (“Failure to Launch“), but more importantly, it relied on a metric of success—Twitter listener numbers—that was irrelevant to the Iowa caucus goer or the New Hampshire primary voter.

The campaign confused the platform (Twitter) with the electorate.

- The Super PAC Data Silo: The “Never Back Down” Super PAC, which handled a massive portion of the field operation, reportedly used a “DeSantis Index” to target voters. This index relied on static demographic data (e.g., “reads the Bible,” “high income”) rather than dynamic sentiment analysis. Leaked audio revealed that leadership was confident in these numbers even as public polling showed a collapse. They were optimizing for a “theoretical” voter profile that their model said should support DeSantis, while ignoring the actual sentiment of voters who were flocking to Trump.

- Sentiment vs. Engagement: Analysis by Impact Social showed that while DeSantis had high engagement in right-wing online circles (vanity), his Net Sentiment among swing voters was consistently negative (impact). The campaign’s internal feedback loops failed to capture this distinction, leading them to double down on “Terminally Online” culture war issues that alienated the broader electorate.

2.3 The Romney ORCA Failure : Infrastructure as a Vanity Project

- The Vanity of Sophistication: The campaign touted the complexity and scale of Orca as a metric of its quality. The sheer number of volunteers (30,000+) assigned to use the app was seen as a victory.

- The Reality: On Election Day, the system collapsed. The failure was not just technical; it was a failure of usability metrics. The campaign had not stress-tested the human element. Volunteers were given incorrect login credentials, the URL was communicated without the necessary https protocol (leading to connection errors), and the load balancers failed under traffic.

- The Blind Spot: Because Orca failed, campaign leadership spent Election Day believing they were winning based on flawed or nonexistent data. They were “flying blind” while thinking they were flying a “stealth jet“. The metric of “Systems Deployed” is vanity; “System Uptime” and “Successful Logins” are impact.

2.4 Sanders 2020: Enthusiasm vs. Arithmetic

- The Hypothesis: The campaign bet on a massive expansion of the electorate, specifically among young voters and non-voters.

- The Data: In the early states, Sanders won the popular vote, fueling the narrative. However, impact metrics in the underlying data were flashing red. In key Super Tuesday states, Sanders was actually running behind his 2016 vote totals in rural counties and among working-class voters. The “youth turnout miracle” required to validate his theory of the case (an 11-point jump) was statistically improbable and arguably “bogus” based on historical trends.

- The Lesson: High enthusiasm among a core base (vanity) often masks a lack of breadth. The campaign’s dashboard needed to track “Expansion of the Electorate” (new voters) separately from “Mobilization of the Base.” When the new voters didn’t show up in the numbers predicted by the rallies, the campaign had no Plan B.

Chapter 3: The Science of Persuasion

Campaigns have two primary interactions with voters: Mobilization (getting your supporters to the polls) and Persuasion (convincing undecideds to become supporters). While mobilization is a logistical challenge, persuasion is a psychological one. Measuring it requires the most sophisticated tools in the political arsenal.

3.1 The “Null Effect” of General Campaigning

A meta-analysis of 40 field experiments in general elections found that the average persuasive effect of candidate contact (mail, phone, canvass) was zero. This startling finding suggests that the vast majority of campaign spending is wasted on voters who are either “Sure Things” (already voting for you) or “Lost Causes” (never voting for you). The traditional method of targeting—using a 1-100 “Support Score” and targeting the middle —is flawed. A voter might be a “50” because they are genuinely torn (persuadable) or because the model has no data on them (unknown). Treating them the same is inefficient.

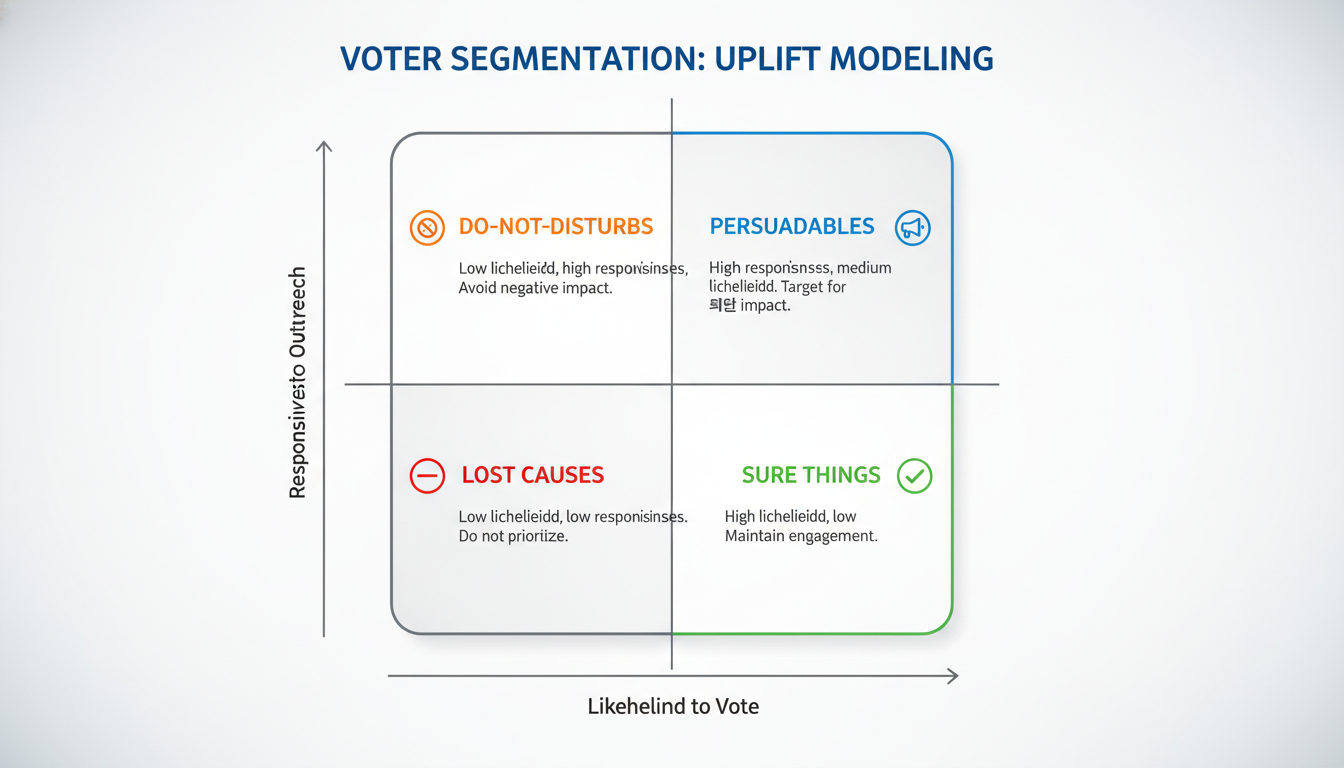

3.2 Uplift Modeling: The Quadrant of Persuasion

To identify the elusive “Persuadable” voter, sophisticated campaigns use Uplift Modeling (also known as Persuasion Modeling). Unlike propensity modeling, which predicts what a voter will do, uplift modeling predicts how a voter will react to a specific intervention.

Uplift = P(Vote | Treatment) – P(Vote | Control)

This segmentation divides the electorate into four quadrants, dictating distinct strategies:

Table 3.1: The Uplift Quadrants

| Segment | Description | Uplift Score | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persuadables | Voters who will vote for you only if contacted. | High Positive | Prioritize. Allocate 80% of the persuasion budget here. This is the only group where ROI exists. |

| Sure Things | Voters who will vote for you regardless of contact. | Zero / Low | Ignore (for persuasion). Monitor for GOTV only. Spending money here is “preaching to the choir.” |

| Lost Causes | Voters who will never vote for you. | Zero / Low | Ignore. Do not waste resources trying to convert the unconvertible. |

| Do-Not-Disturbs | Voters who will vote against you if contacted (Backlash effect). | Negative | Suppression. Remove from all lists. Contacting them actively hurts the campaign. |

Implication for Dashboards: A standard dashboard reports “Voters Contacted.” An impact dashboard reports “Persuadables Contacted.” If the campaign contacts 10,000 “Sure Things,” the persuasive impact is zero, but the vanity metric looks great.

3.3 The Methodology of Randomized Control Trials (RCTs)

To build an uplift model, the campaign must generate experimental data. This is done via RCTs, the gold standard of causal inference.

The RCT Workflow:

- Universe Selection: Select a target population (e.g., suburban women in swing districts).

- Random Assignment: Split the universe into a Treatment Group (receives digital ads/mail) and a Control Group (receives nothing). The split must be truly random to eliminate selection bias.

- Intervention: Execute the campaign tactic on the Treatment Group.

- Measurement: Conduct a survey of both groups (or wait for Election Day results if possible) to measure support levels.

- Analysis: The difference in support between the Treatment and Control groups is the Average Treatment Effect (ATE).

Key Findings from Research:

- The “Costly Signal” Theory: Research suggests that personal contact (canvassing) works not because of the message content, but because it serves as a “costly signal” of the candidate’s quality. Voters perceive that a candidate who organizes volunteers to knock on doors is more viable and committed. Thus, the medium is the persuasion.

- Gender Differences: RCTs have shown heterogeneous effects based on gender. For example, negative campaigning can demobilize female voters while mobilizing male voters (or vice versa depending on context), necessitating gender-stratified uplift models.

- Decay: The persuasive effect of early contact decays rapidly. An RCT conducted in June may show a +5% lift, but that effect may be zero by November. This requires “refresh” experiments.

3.4 Cost Per Persuadable (CPP)

The financial metric for persuasion is not CPM (Cost Per Mille) or CPC (Cost Per Click), but Cost Per Persuadable (CPP).

CPP = Total Campaign Spend / Number of Persuadable Voters Converted

Example:

- Campaign A: Spends $100,000 on TV ads. Reach = 1M. Lift = 0.1%. (1,000 votes gained). CPP = $100.

- Campaign B: Spends $100,000 on deep canvassing. Reach = 20,000. Lift = 10%. (2,000 votes gained). CPP = $50.

- Result: Campaign B is twice as efficient, despite having “lower reach” (vanity). The dashboard must highlight this efficiency.

Chapter 4: Field Operations – From Output to Outcome

The Field Department is the campaign’s “ground game.” It is labor-intensive, logistically complex, and prone to the most egregious vanity metrics. The classic measure of field success—”Doors Knocked“—is a measure of effort, not effect.

4.1 The Fallacy of Volume

A volunteer can knock on 60 doors an hour if they walk fast and nobody is home. This generates a high “Knock” count but zero political capital. In fact, it burns through turf without generating data.

The Shift to Impact Metrics:

- Contact Rate: The percentage of knocks that result in a conversation.

- Benchmark: A healthy contact rate is 15-20%. If it drops below 8%, the campaign is wasting volunteer time.

- Factors: Time of day, quality of the list, neighborhood density.

- Conversion Rate: The percentage of conversations that result in a purely identified supporter or a volunteer recruit.

- Shift Rate (Deep Canvassing): For persuasion programs, the metric is the movement on a 1-10 support scale during the conversation. A shift from a “5” to a “7” is a measurable unit of persuasion.

4.2 Volunteer Management: Retention as a KPI

Volunteers are the lifeblood of the field. Treating them as disposable labor leads to “Churn“—a high turnover rate that depletes the campaign’s training resources and institutional memory.

Volunteer Metrics for the Dashboard:

- Volunteer Retention Rate: The percentage of volunteers who complete a shift and return for a second shift within 14 days.

- Target: >60%.

- Flake Rate: The percentage of scheduled volunteers who do not show up.

- Warning Sign: A flake rate >30% indicates poor confirmation calls or a lack of enthusiasm.

- Volunteer Efficiency: (Contacts Made / Volunteer Hours).

This helps identify “Super Volunteers” who should be promoted to leadership.

4.3 The “Ground Truth” Feedback Loop

Modern field programs must function as listening devices. The “Ground Truth” program, pioneered by organizations like Swing Left, emphasizes the collection of qualitative data.

- Mechanism: Canvassers record not just support scores, but specific notes on voter concerns (e.g., “Voter is angry about the new zoning law”).

- Technology: Utilizing Natural Language Processing (NLP) on these notes can reveal localized trends before polling picks them up.

- Application: If 20% of notes in District 9 mention “potholes,” the candidate’s talking points for the District 9 rally should pivot to infrastructure immediately. This turns the field program into a real-time focus group.

4.4 The Technology Stack: NGP VAN vs. Qomon

The choice of field software dictates the data structure.

Table 4.1: Field Technology Comparison

| Feature | NGP VAN (MiniVAN) | Qomon | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Ecosystem | The “Standard” for Democrats. deeply integrated with the central voter file and fundraising tools. | Independent / International. Flexible data imports/exports. | VAN is essential for partisan campaigns requiring voter file sync. Qomon is superior for non-partisan or grassroots movements. |

| User Experience | Functional, utilitarian. “Cut turf” model. | Mobile-first, gamified. “Citizen engagement” focus. | Qomon’s gamification features (badges, leaderboards) can improve volunteer retention and data collection rates. |

| Mapping & Routing | Standard list-based routing. | AI-optimized routing; territory overlays (census data). | Qomon allows for visual “territory management” that helps Field Directors see coverage gaps intuitively. |

| Feedback Loop | Structured data (Support Scores, IDs). | Richer qualitative data input; real-time sync. | Qomon facilitates the “Ground Truth” approach with better note-taking interfaces. |

The “Vanual” Best Practices:

According to the “Vanual” (the unofficial guide to VAN), successful campaigns use the “ActionID” to track volunteer history across cycles, allowing them to re-activate experienced canvassers from previous elections—a key efficiency metric.

Chapter 5: Digital Strategy & Media Math

Digital campaigning is the most data-rich environment, yet it is plagued by “black box” reporting where agencies report vanity metrics (Impressions) to justify their fees, while obscuring the true cost of impact.

5.1 The Hierarchy of Digital Metrics

To govern digital spend, leadership must distinguish between three levels of metrics:

- Level 1: Vanity (Reach)

- Metrics: Impressions, Views (3-second), Clicks, Followers.

- Utility: Validating that the ads are running. Do not use for optimization.

- Level 2: Engagement (Resonance)

- Metrics: Click-Through Rate (CTR), Video Completion Rate (VCR), Share Rate.

- Utility: Judging the quality of the creative. If Ad A has a 50% VCR and Ad B has 10%, Ad A is the better message.

- Level 3: Impact (Conversion)

- Metrics: Cost Per Acquisition (CPA), Cost Per Donation (CPD), Lift Rate.

- Utility: Budget allocation. Shift money to the platform/creative with the lowest CPA.

5.2 Attribution Modeling

In a multi-channel world, determining which ad caused a donation or vote is complex.

- First-Touch Attribution: Credits the first ad the user saw. Good for measuring Awareness.

- Last-Touch Attribution: Credits the last ad clicked before conversion. Good for measuring Closing.

- Multi-Touch Attribution: Distributes credit across the journey. This is the most accurate but requires advanced tracking (pixels, server-side API conversions).

- The “Cookie-less” Challenge: With Apple’s ATT (App Tracking Transparency) and the decline of cookies, campaigns are moving toward Media Mix Modeling . This statistical technique correlates aggregate ad spend changes with aggregate outcome changes (e.g., “When we doubled YouTube spend, fundraising went up 15%”), bypassing the need for individual user tracking.

5.3 AI in Digital: The Double-Edged Sword

The 2024 cycle introduced Generative AI as a standard tool.

- Microtargeting: AI can generate thousands of ad variations (text, image, tone) to match specific voter personas. Research indicates AI-targeted ads can achieve a 70% higher persuasive impact than generic ads by aligning the message with the voter’s psychological profile.

- Disinformation Defense: Campaigns must deploy AI-powered “Social Listening” to detect deepfakes (like the Biden robocall) instantly. The metric here is Time to Detection. A deepfake that circulates for 48 hours does irreparable damage; one detected in 2 hours can be debunked.

5.4 Sentiment Analysis: The Digital Focus Group

Beyond ad performance, digital teams must monitor Net Sentiment.

- Share of Voice (PSOV): What percentage of the online political conversation is about our candidate?

- Sentiment Score: Is that conversation Positive, Negative, or Neutral?

- Methodology: Tools like Determ or Zencity scrape social media, news, and blogs. They use NLP to assign a sentiment score (-100 to +100).

- Insight: A drop in Net Sentiment among “Swing Voter” segments often precedes a drop in polling numbers by 3-5 days. It is a leading indicator.

Chapter 6: Financial & Operational Health

A campaign is a startup that must spend 100% of its revenue by a fixed date (Election Day). This creates unique financial pressures.

6.1 The Burn Rate and The Runway

- Cash on Hand (COH): The actual liquid assets available.

- Burn Rate: The average daily or weekly expenditure.

- Runway: (COH / Burn Rate) = Days until insolvency.

- Strategic Metric: Cost to Raise a Dollar. If the campaign spends $0.50 to raise $1.00, it is inefficient. Direct mail often has a high cost; digital solicitation usually has a lower cost. Leadership must monitor this ratio to prevent “fundraising for the sake of fundraising”.

6.2 Call Time Efficiency

For many candidates, “Call Time” (dialing donors) is the most miserable part of the day. Optimizing it is crucial.

- Metric: Dollars Raised per Hour of Call Time.

- Diagnosis: If the rate is low, either the candidate is bad at asking (training needed) or the list is bad (Finance Director needs to research better donors). Tracking “Dials per Hour” ensures the candidate isn’t stalling.

6.3 Infrastructure Integrity: The Lesson of ORCA

Operational data integrity is non-negotiable. The collapse of Romney’s Project Orca in 2012 was a failure of infrastructure reliability metrics.

- The Error: The campaign focused on the features of the app (vanity) rather than its stability (impact). They failed to monitor “Server Load Capacity” and “User Login Success Rate” during testing.

- The Fix: Modern campaigns must track System Uptime and Data Sync Latency. If the voter file takes 12 hours to sync, the data is stale. It should be near real-time.

- Data Hygiene: The “Garbage In, Garbage Out” rule applies. A Duplicate Rate metric helps the Data Director identify if the database is becoming cluttered with duplicate voter records, which wastes money on double-mailing.

Chapter 7: Dashboards for Leadership

A dashboard is a decision-support tool, not a museum of data. It should answer the question: “Are we winning?” and “What do we need to fix today?”

7.1 Design Principles

- Simplicity: Restrict the dashboard to 5-7 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Cognitive load is the enemy of decision-making.

- Context: Use traffic light logic (Red/Yellow/Green) based on goals. A number is meaningless without a target.

- Audience-Specific: The Candidate needs a different view than the Field Director.

7.2 The Campaign Manager’s “Single Pane of Glass”

Purpose: Strategic Health Check.

| Widget | Metric | Visualization | Source | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top Left (The Goal) | Vote Goal Progress | Gauge Chart | Model/Polls | % of Win Number achieved (Banked + Projected). |

| Top Right (Finance) | Cash on Hand | Big Number | Finance DB | Color-coded against weekly budget target. |

| Center (Momentum) | Net Sentiment (Swing) | Line Graph | Social Listening | 7-day rolling average. Watch for spikes. |

| Bottom Left (Field) | Contact Rate | Bar Chart | VAN/Qomon | Actual contacts vs. Goal. |

| Bottom Right (Ops) | Days to Election | Countdown | Calendar | Creates urgency. |

7.3 The Field Director’s Tactical Dashboard

Purpose: Labor Optimization.

- Active Volunteers: Live count of users in MiniVAN/Qomon.

- Turf Completion %: Map visualization showing which precincts are covered (Green) and which are untouched (Red).

- Contact Rate Heatmap: Identifies high-performing vs. low-performing regions. Action: Re-train or re-deploy volunteers from low to high performing areas.

7.4 The Digital Director’s Optimization Dashboard

Purpose: Spend Efficiency.

- CPA by Channel: Comparison of Facebook, Google, Connected TV. Action: Shift budget to lowest CPA.

- Creative Fatigue: Frequency metric. If Frequency > 10, pull the ad.

- Donation Volume: Real-time ticker of online fundraising.

Chapter 8: Future Trends and Ethical Considerations

8.1 The “Sentient” Campaign

The future of campaign data lies in Predictive and Prescriptive Analytics.

- Predictive: “Based on current trends, we will lose District 5 by 200 votes.”

- Prescriptive: “To fix this, spend $5,000 on ‘Healthcare’ ads in District 5.” AI systems will soon automate these recommendations.

8.2 The Voter Sentiment Index (VSI)

Future dashboards will integrate a standardized Voter Sentiment Index, aggregating polling, social sentiment, and economic indicators into a single “stock price” for the campaign.

This provides a holistic view that prevents the “blind spots” seen in the Beto and DeSantis campaigns.

The Ethics of Data

As targeting becomes more precise, the line between persuasion and manipulation blurs.

- Privacy: Campaigns must navigate the “creepy” factor. Using personal health data or location data to target voters can backfire if discovered.

- Transparency: Ethical campaigns should self-regulate by ensuring that AI-generated content is labeled.

- The “Do-Not-Disturb” Responsibility: Respecting voters who ask to be removed is not just good ethics; it is good data hygiene (preventing backlash).

Conclusion: The Human Element

Data is a map, not the terrain. The most sophisticated dashboard cannot replace the intuition of a candidate or the passion of a volunteer. However, in a game of inches—where elections are decided by fractions of a percentage point—the campaign that navigates by the stars of Impact Metrics will always have the advantage over the one chasing the mirage of Vanity. The transition from “feeling good” to “doing good” is the hardest, most necessary step on the road to victory.